10 Bobcat Ceremonial Burial

While going through the Illinois State Museum’s collection of Native American artifacts, anthropologist Angela Perri found a box labeled “puppy” which she expected to be filled with dog bones excavated from a burial mound of the Hopewell culture. Instead, the bones belonged to a bobcat. The discovery was notable for two reasons: It was the only decorated wildcat burial found in North America and the only animal ever found buried alone in its own mound. Since the bobcat was only a kitten when it died, anthropologists suspect that it was raised as a pet. Inside the mound, they also found a necklace which Perri believed served as the cat’s collar. However, zooarchaeologist Melinda Zeder has a different hypothesis. She believes that the bobcat held a much higher symbolic status for the native culture, possibly as a connection to nature.

9 Roman Terror Weapons

A recent discovery suggests that the Romans employed psychological warfare using whistling slingshot bullets. They used a staff sling called a fustibalus which could throw lemon-sized rocks over a long distance. But certain bullets found at one site in Scotland have a peculiar characteristic—they are drilled through their center. The stone bullets were found at Burnswark Hill, the site of a massive fight between Romans and Scots about 1,800 years ago. Drilling the holes would have been a time-consuming endeavor, especially for something used only once. Archaeologist John Reid was puzzled by the stones’ purpose. But Reid’s brother, a keen fisherman, deduced the purpose of the bullets based on his experience of using holed-out lures. When thrown, the bullets caused a sharp whistling noise. Only small stones were drilled, so multiple bullets could be thrown at once, creating a stereo effect for added terror.

8 Celtic Hybrid Boneyard

Until recently, we didn’t think that Iron Age Celtic mythology contained hybrid monsters. Now, one gravesite in Dorset suggests that the Celts had their own mythological creatures which they recreated in real life. The discovery was made at Duropolis. The “cemetery” consists of pits with animal skeletons rearranged to form hybrid beasts. These include a cow with horse legs and a sheep with a bull’s head on its rear end. The most bizarre discovery involved the skeleton of a woman found on top of a layer of animal bones which mirrored the arrangement of the human bones. Her head was resting on a “bed” of animal skulls, her legs were on top of animal leg bones, etc. Archaeologist Paul Cheetham believes that the skeletons (including the woman) represent sacrifices. The pits were initially used as food storage. When a new pit was dug, a sacrifice was placed in the old one before being buried.

7 Oldest Dress In The World

The Tarkhan Dress is now the oldest woven garment in the world. Recovered from an Egyptian tomb, it is dated between 3400 BC and 3100 BC. Most recovered ancient clothing is no older than 2,000 years because neither animal skins nor plant fibers survive degradation well. The dress has a V-neck, narrow pleats, and tailored sleeves. Creases formed at the elbows and armpits indicate that it was worn repeatedly. There are a few clothing items of similar age, but those are ceremonial garments wrapped or draped over a body. The Tarkhan Dress remains a unique ancient Egyptian fashion statement as it was tailor-made by a specialized craftsman and worn by somebody of great wealth.

6 Philadelphia’s History Down The Toilet

In 2017, Philadelphia will open the Museum of the American Revolution. When excavation for the museum started in 2014, workers uncovered a system of privies that served households and businesses in the 18th century. The pits were literally clogged with historical items, and so far, archaeologists have recovered over 82,000 artifacts. At that time, privies also served as garbage dumps for household waste. While these items might not have immense value, some historians prefer them over jewelry or art for the unique look they provide of common people of that time. One especially fascinating pit belonged to Benjamin and Mary Humphreys and was dug around the start of the American Revolution. Although their house was registered as a private residence, archaeologists found tobacco pipes, broken punch bowls, and empty liquor bottles there. In 1783, Mary was arrested for running a “disorderly house.” The couple was actually running an illegal tavern.

5 First Philistine Cemetery

The Philistines were a mysterious ancient people heavily featured in the Bible and described as the archenemies of the Israelites. In modern times, certain historians considered the Philistines a sea people, likely Aegean in origin, who came to Levant, settled in five main cities, and formed the pentapolis of Philistia. The Philistines disappeared around the eighth century BC with little trace, but archaeologists recently announced the discovery of a Philistine cemetery with over 150 graves and countless artifacts. The cemetery was actually discovered 30 years ago, but it took this long to excavate it. No bones have been analyzed so far, but the burial of the dead sheds light on Philistine society. The discovery reveals that the Philistines were not hostile to culture despite their name. They were buried with jewelry, decorated jugs filled with perfumed oils or wine, and weapons.

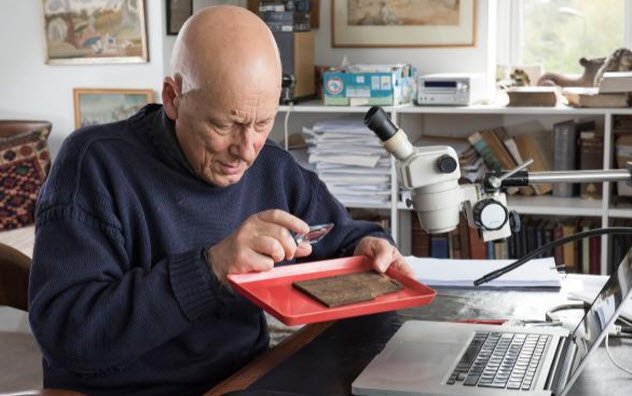

4 Oldest Document Of Roman Britain

While excavating for Bloomberg’s new European headquarters in London, workers uncovered the largest collection of Roman writing tablets in Britain’s history. The collection contains around 400 tablets and boasts the earliest mention of London, predating Tacitus’s Annals by 50 years. The still-legible tablets have been translated and published in a monograph titled Roman London’s First Voices, which provides us with unparalleled context for life in Londinium 2,000 years ago. The find also contains the oldest document of Roman Britain, dated January 8, AD 57. The document is an IOU, fittingly found in London’s financial district. It specifies that Tibullus, freedman of Venustus, owes Gratus, freedman of Spurius, 105 denarii for merchandise which was sold and delivered.

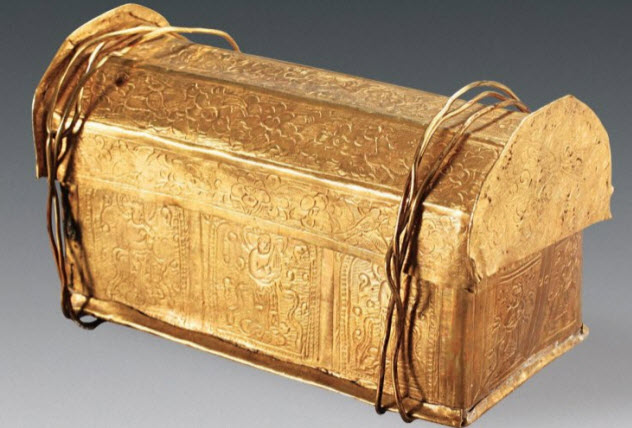

3 Buddha’s Skull Bone

Between 2007 and 2010, archaeologists excavated a Buddhist temple in Nanjing. The highlight of the find was a 1,000-year-old model stupa which contained the remains of several saints. The stupa might have also contained the most revered Buddhist artifact in history—the skull bone of Buddha. The inscriptions make it clear that the parietal bone placed inside the chest belonged to Buddha. It was sent to the temple after his body was cremated in India around 2,400 years ago. About 1,400 years ago, the temple was destroyed by war and rebuilt by Emperor Zhenzong of the Song dynasty. The description even names the people who donated money and materials to build the new temple. It’s difficult to say if the parietal bone belonged to Siddhartha Gautama. Buddhists already revere it and visit it in pilgrimage. The Western world just found out because the discovery has only recently been covered in English.

2 Untouched Mycenaean Tomb

A minor excavation of a stone shaft turned into one of the biggest Greek archaeological finds in decades. Explorers uncovered the intact 3,500-year-old tomb of a Mycenaean warrior. Although the warrior remains unidentified, he must have been quite wealthy and important as he was buried with over 1,400 objects displayed on and around his body. We have little information about the infant stages of Mycenaean Greece around 1,500 BC. In fact, the dig was part of an ongoing project to determine the influential extent of Mycenaean culture on the Minoan civilization and vice versa. Already, the tomb has raised several questions for archaeologists. Among the warrior’s possessions were beads, combs, and a mirror, objects typically buried with wealthy women. Group burial was common practice back then, even for Mycenaean elite. One such grave was found just 90 meters (300 ft) away from the tomb, which makes archaeologists question why this Mycenaean warrior was buried alone.

1 Oldest Stone Tools

Using tools is considered an essential step in the evolution of mankind. The Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania used to be the place where the earliest toolmaking practice (known as the Oldowan industry) occurred. The oldest tools recovered there were 2.6 million years old. Now we’ve found tools which are 700,000 years older. On the shores of Lake Turkana in Kenya, archaeologists discovered sharp stone flakes for cutting that are 3.3 million years old. The most significant implication is that the tools predate humans. Until this point, we thought that the first tools were made by members of the Homo genus, but it seems that earlier hominins also developed this skill. The most likely culprit is Kenyanthropus platyops. It’s a fossil discovered in the same area in 1999 that some claim should be its own genus. Others see it as a species of Australopithecus.