10Jeronimo De Aguilar

At some point between 1509 and 1511, a Spanish ship was cruising the Caribbean in search of slaves when it was hit by a sudden storm and ran aground on a reef. The crew escaped to a small skiff, which drifted for a fortnight before washing up on a beach on the Yucatan coast. There, they were discovered by a group of local Maya who fed them corn, meat, and chocolate, but also kept them in wooden cages. Supposedly, the captain ate so ravenously that he became exceedingly fat, and one day a group of warriors carried him off to be roasted alive. The remaining Spaniards broke free from their cages and fled, only to be captured by a different group of Maya, who decided to enslave them rather than eat them. Most of them eventually died, except for two: Gonzalo Guerrero and Jeronimo de Aguilar. Guerrero would eventually become a respected member of Mayan society, teaching them Spanish military tactics and marrying a local woman. Aguilar, on the other hand, was a priest and completely refused to marry into the Mayan community. This made him the subject of ridicule, although he was treated fairly well otherwise. (His chastity eventually led the local chief to appoint him keeper of his harem.) While Guerrero completely assimilated into his new society, to the point that some accounts have him dying in battle against his fellow Spaniards, Aguilar never truly belonged. His chance to escape came when the famous conquistador Hernan Cortes landed in Yucatan during his expedition against the Aztecs. Aguilar quickly became Cortes’s translator, even though he only spoke Mayan and not the Nahuatl of the Aztecs. His job was eventually stolen by La Malinche, a young Tabascan who spoke both languages and eventually became Cortes’s consort to boot. As compensation for his services, Aguilar was granted a property in the Valley of Mexico, where he settled down in his old age. Despite his earlier insistence on priestly abstinence, he started a relationship with a local woman and they eventually had two daughters.

9Yasuke

The Japanese first encountered black people via European traders in the 16th century. Dark skin was associated with India, and the Japanese placed Southern Indians, Malay-Indonesians, and Africans into a single category called kurobo. (To be fair, the Japanese also initially assumed that Europeans were from somewhere in India.) The Japanese would come from miles around to catch a glimpse of a black visitor, with crowds often whipping themselves into a frenzy at the exotic sight. In 1581, a hysterical mob broke down the doors of the Jesuit residence in Kyoto after hearing of a young slave brought from Mozambique, causing several injuries in the process. Embarrassed by the incident, the warlord Oda Nobunaga demanded to see the man and had him stripped and washed to test if his skin color was real. Apparently satisfied, and impressed by the man’s size, strength, and knowledge of the Japanese language, Nobunaga bestowed the name “Yasuke” upon him and took him on as a retainer. Later, Yasuke stood alongside Nobunaga in his last stand against the traitorous Akechi Mitsuhide. Fleeing to Nijo Castle with Nobunaga’s heir, Oda Nobutada, Yasuke continued to fight until Nobutada committed suicide in the face of certain defeat. Upon surrendering, Yasuke is said to have given up his sword, implying he was considered a samurai. Akechi spared his life, stating the obvious: “He is not Japanese.” Akechi apparently sent Yasuke to a church in Kyoto, but no record survives of what happened to him next. While Yasuke was the most prominent African in Japan during this period, he was far from the only example—many daimyos employed Africans as soldiers, gunners, drummers, and entertainers. The Dutch settlement at Deshima usually included a few African slaves, who frequently intermingled with the locals. Some even kept Japanese slaves and mistresses of their own.

8Jan Janse Weltevree

In 1627, three shipwrecked Dutch sailors washed up unexpectedly in Korea. The men were formerly of the Ouwerkerck, a privateer operating on behalf of the Dutch East India Company. The Ouwerkerck had just captured a Chinese junk and its crew when a storm blew up and separated the two vessels. The junk, including the three Dutch sailors, was blown to Korea’s Jeju Island. Once the Chinese regained control and sailed off, the three Dutchmen were captured by the Koreans. Although the Dutchmen were expecting decapitation, they were instead recruited to help produce cannon, the only caveat being that they were never allowed to leave. Two of the men died during the Manchu invasion of 1636, while the last man, a tall, red-haired, blue-eyed giant named Jan Janse Weltevree managed to impress the Joseon court with his knowledge of firearms. He was granted the Korean name of Pak Yon, middle-class status, a military post, and allowed to marry a Korean woman. His children became gunsmiths and interpreters thanks to their father’s status and knowledge. After decades in Korea, Weltevree was sent back to Jeju to interview shipwrecked Dutch sailors under the command of Hendrick Hamel. Communication was initially difficult as Weltevree had largely forgotten Dutch by that point, but the sailors were eventually recruited into the Joseon military as musketeers, although eight of them later escaped in a skiff and made their way to Japan. Hendrick Hamel himself later wrote one of the first accounts of Korea in a Western language. Weltevree’s fate after that point remains unknown, but his name lives on in a district of Jakarta named Weltevreden.

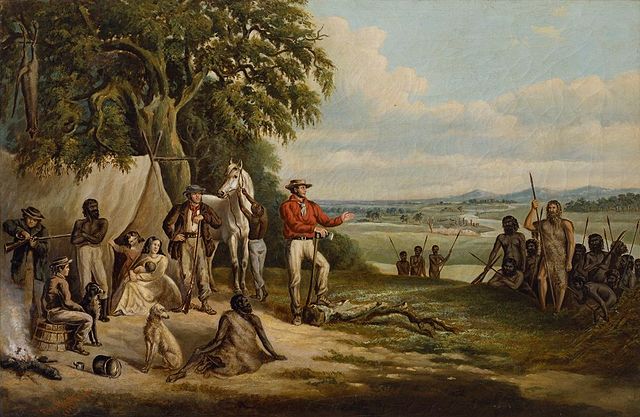

7William Buckley

A giant of an Englishman, William Buckley was wounded fighting the French in Holland and worked as a bricklayer. In 1803, he was sentenced to be transported to Australia for stealing a roll of cloth worth a few shillings. Sent to help found a new colony, he laid the first brick of what would become the city of Melbourne. Eventually, he made a break for freedom with some companions. While the others quickly gave up and returned to the colony, Buckley pushed on. Traveling up the coastline, he survived by eating berries and shellfish until one day he discovered an Aboriginal spear sticking out of a mound of sand. Taking the spear to use as a crutch, he soon encountered two women from the Wathaurung people. Recognizing the spear as belonging to a dead relative named Murrangurk (also very tall), they assumed that Buckley was his reincarnated spirit and accepted him into their community. Buckley lived among the Wathaurung for the next 32 years, learning their customs, taking wives, and having a daughter. One day, a group of Wathaurung kids showed Buckley some colored cloth they had been given by white men. Following their directions to an encampment, Buckley surrendered himself to the authorities, but found that he could no longer speak English. Luckily, when offered a slice of a loaf, Buckley suddenly remembered how to say “bread” and repeated the word over and over until he could recall more. A surveyor named John Wedge arrived the next day and recognized Buckley from the “WB” tattooed on his arm. Realizing his usefulness as a translator, Wedge successfully applied to have Buckley pardoned. He worked as an interpreter between the British and the Wathaurung, but felt distrusted by both, and eventually retired to Hobart, where he married a widow. Australians still use the expression “Buckley’s chance” to refer to a slim possibility.

6Edward Day Cohota

In 1845, the US ship Cohota had just left Shanghai when Captain Silas S. Day discovered two malnourished Chinese boys in the hold. The older boy died, but Captain Day decided to adopt the younger one, whose original name was supposedly Moy. Growing up as a cabin boy aboard the Cohota, he eventually took the name of the ship as his own. In February 1864, Cohota joined the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry and spent the next 16 months fighting for the Union in the US Civil War. At the battle of Cold Harbor, Cohota was struck by a rifle bullet that permanently parted his hair. Later during that same battle, he saved the life of his comrade William Low, carrying him to a field hospital after he had been shot in the jaw. Unable to find work after being mustered out, Cohota re-enlisted in 1865 and spent the next 20 years serving in Texas, New Mexico, Illinois, South Dakota, and Nebraska. At Fort Randall in South Dakota, he stood guard over a captured Sitting Bull, describing him as a “friendly chief.” After each tour, he would simply re-enlist, despite once being banished from Fort Sheridan for drinking and operating a gambling house. Eventually, Cohota settled down with a Norwegian girl, had six children, opened a restaurant, and became a Freemason. Despite his many achievements, he was denied US citizenship due to the anti-immigrant Chinese Exclusion Act. His story gained national media attention and the support of the chairman of the immigration committee, but to no avail. Finally, in 2006, the House of Representatives formally honored Cohota and other Asian Americans who fought in the Civil War. At least one other Chinese immigrant, Joseph L. Pierce (pictured above), fought for the Union, while the Confederacy conscripted a number of Chinese, including a Florida cigar salesman named John Fouenty, who fled to the Union Army at St. Augustine and eventually returned to China.

5Abram Petrovich Gannibal

Around 1705, a young African slave was bought by the Russian envoy to Constantinople and sent to Peter the Great as a gift. The boy had been born in what is now Cameroon, captured by a rival tribe, and sold to Arab slavers. The Tsar took to the boy, and stood as his godfather when he was baptized into the Orthodox Church. He assumed the name Abram Petrovich Gannibal, taking his patronym from Peter and his last name from the legendary Carthaginian general Hannibal. Peter the Great is said to have sought to educate the young African to teach the Russian nobility that anyone could become a learned and valuable asset through hard work and study. He became part of the Tsar’s military entourage and accompanied Peter on campaigns for a decade before being sent to France for his education. He served in the French army, studied mathematics and engineering, and was able to acquire a library of some 400 books despite a meager stipend from Moscow. Given the rank of engineer-lieutenant, Gannibal next spent time instructing Russian officers on military engineering and artillery. After Peter the Great’s death in 1725, Gannibal became tutor to his heir, Peter II, but ran afoul of Prince Menshikov, advisor to the Empress Catherine. Jealous of Gannibal’s position, Menshikov had him sent to Siberia, ostensibly to build fortifications in the remote outpost of Selenginsk . After Menshikov’s fall from power, Gannibal returned from exile and married a Greek woman named Evdokia Dioper, who apparently objected to the match since her new husband was “not our breed.” Predictably, things ended badly, with Gannibal accusing his wife of flagrant infidelity and Evdokia accusing her husband of torturing her in a secret chamber. The divorce proceedings lasted 21 years. By that point, Gannibal had married again, this time to Christina Regina von Schoberg, the daughter of a Swedish army captain, with whom he would have seven children. He was brought back from retirement in 1741 to serve as a military engineer in the city of Revel. The following year, the new Empress Elizabeth promoted him to general. When he died in 1781, Gannibal had become one of the most important figures in the Imperial Russian military. Today, he is probably best-known as the great-grandfather of famous poet Alexander Pushkin. More recently, Dieudonne Gnammankou, a historian from Benin, has claimed that Gannibal was most likely the son of a chief in the Logone-Birni sultanate.

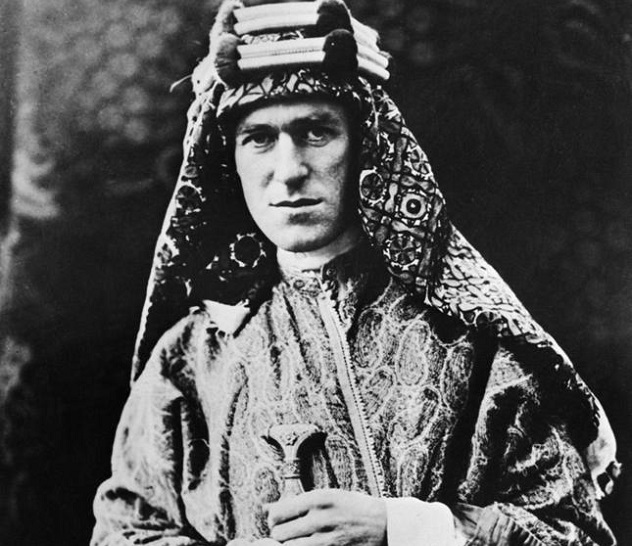

4T.E. Lawrence

Born in 1888, Thomas Edward Lawrence was an odd child: secretive, curious, skeptical, and deeply interested in medieval history and archaeology. As a teenager, he would scour building sites for fragments of pottery and restore them for museums. After training at Oxford University, he went to an archaeological dig in Palestine, where he studied Arabic and developed a sympathy for the Arab subjects of the Ottoman Empire. He was unique among the British working at the site for his interest in the Arab workers, their clans and tribes, and their family life. The dig came to an abrupt end with the outbreak of World War I, and Lawrence was sent to Egypt as an intelligence officer. In 1916, Emir Hussein, ruler of the Hejaz region of central Arabia, launched a revolt against the Ottoman rule, which was initially beaten back. Lawrence went to Arabia to look into the situation and won the trust of Hussein’s third son and chief military commander, Faisal, through his knowledge of Arab clan and tribal political structures. Appointed as liaison to Faisal, Lawrence was accepted as an honored member of tribal strategy meetings. As the revolt grew and more tribes joined, Lawrence felt increasingly guilty, as he was aware of a secret agreement between France and the UK known as Sykes-Picot. While Lawrence and the British had promised the Arabs full independence, Sykes-Picot planned to limit the scope of any independent Arab state to the wastelands of the Arabian peninsula. After agonizing over the situation, Lawrence betrayed the British by telling Faisal of the plan and taking an Arab force to seize the Ottoman port of Aqaba in a daring, camel-mounted assault. (Lawrence somehow managed to shoot his own camel in the head during the melee.) Lawrence knew an Anglo-French amphibious assault was planned on Aqaba, which would seal in the Arabs. He then bluffed the British high command as to the size of the Arab forces. As a result, the French were sidelined and British and Arab forces worked together to push north. Lawrence was briefly imprisoned by the Turks and tortured, after which he became unhinged and merciless toward captives. After the fall of Damascus in October 1918, Lawrence left to lobby for Arab independence, but the French and British had already decided against a united Arab state. Disillusioned, and now an unwilling celebrity, Lawrence avoided the spotlight by serving in the RAF and Tank Corps under assumed names. He died in a motorcycle accident in 1935.

3Hasekura Tsunenaga

In 1613, Japanese leader Date Masamune sent an embassy to Spain and the Vatican to negotiate direct trade links with Spanish Mexico. This was actually the second Japanese delegation to visit Europe: four young Japanese princes went on a Jesuit-organized mission to Rome in 1582. The second embassy, the Keicho Mission, was more significant. Led by Masamune’s retainer Hasekura Tsunenaga and Franciscan friar Luis Sotelo, the Keicho Mission sailed across the Pacific in a European-style vessel built in Japan and passed through Mexico and Cuba before arriving in Europe. The mission was ostensibly about trade and requesting more Christian missionaries for Japan, but Date may also have been hopeful Papal recognition would help secure European weapons and assure his independence from the Tokugawa. Spending eight months in Spain, Tsunenaga was baptized and met with Spanish high officials. He failed to secure trade agreements or missionaries, however, as the Spanish were concerned about the increasing hostility toward Christianity in Japan. The Keicho Mission then moved on to Rome, where Tsunenaga was given an audience with Pope Paul V. The Pope’s nephew, Scipione Borghese, commissioned a portrait of the visitor (pictured above), which featured Tsunenaga’s family crest paired with a crown symbolizing honorary membership of the Roman aristocracy. Unwilling to contradict the Spanish, the Pope also turned down Tsunenaga’s requests. Returning to Japan, the ambassador discovered that Christianity had been banned and Date Masamune had given up plans to declare independence from the Tokugawa. Tsunenaga renounced Catholicism and died in 1622; his family was mostly destroyed in anti-Christian purges over the next few decades. Japan would henceforth limit its contact with Europe to the Dutch alone. One trace of the Keicho expedition remains in the Spanish city of Coria del Rio, where some Japanese retainers decided to settle. Their descendants remain there, distinguished by the surnames “Japon” or “Xapon.”

2Ahmad Ibn Fadlan

In 921, the Abbasid Caliph Jaffar al-Muqtadir dispatched a diplomatic mission to the Volga Bulghars. The embassy’s secretary was Ahmad ibn Fadlan ibn al-Abbas ibn Rashid ibn Hammad, whose name is thankfully usually shortened to ibn Fadlan. His writings are an amazing record of many of the region’s people, including Bulghars, Khazars, and Finno-Ugrians. In 922, ibn Fadlan encountered a group of Viking traders and would go on to produce one of the first detailed written descriptions of the Vikings. The Norse seemed interesting and exotic to ibn Fadlan, and he dedicated around a fifth of his chronicle to a detailed description of their appearance, customs, behavior, dress, trade relations, table etiquette, and sexual mores. Some of his reports were highly flattering: “I have never seen more perfect physical specimens, tall as date palms, blonde and ruddy.” As a writer with an Islamic background used to daily ablutions, he was less impressed by Norse hygiene: “They are the filthiest of God’s creatures. They have no modesty in defecation and urination, nor do they wash after pollution, nor do they wash their hands after eating. Thus they are like wild asses.” Ibn Fadlan also took the opportunity to view the cremation of a Norse chieftain on his ship. During the ritual, a Viking told ibn Fadlan through an interpreter: “You Arabs are fools. You take the people who are most dear to you and whom you honor most and put them into the ground where insects and worms devour them. We burn him in a moment, so that he enters paradise at once.” The story of ibn Fadlan was inexplicably combined with Beowulf in Michael Crichton’s The Eaters of the Dead, which in turn formed the basis of the movie The 13th Warrior.

1Ranald MacDonald

One of the most significant early figures in US-Japanese relations was a young Native American named Ranald MacDonald, who became the first English teacher in Japan. Born in Fort George (present-day Astoria), Oregon in 1824, MacDonald was the son of Archibald MacDonald, a Scot formerly of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and Koale’xoa, a Chinook woman also known as Princess Raven or Princess Sunday. Koale’xoa died shortly after childbirth, so MacDonald grew up initially in the care of his grandfather, Chief Com-Comly. His father eventually enrolled him in school in what is now Portland. MacDonald grew up in a multilingual environment, surrounded by a mix of French, English, Gaelic, Chinook, Iroquois, and other Native American languages. In 1832, the Japanese fishing boat Hojun-maru went off course and floated across the northern Pacific to land near Cape Flattery. The three surviving fishermen were enslaved by the local Makah people before they were rescued by the Hudson’s Bay Company, which hoped they could be used to help open up Japan to trade. It was the story of these three men that first kindled MacDonald’s interest in Japan. MacDonald’s father wanted him to be a banker, but he hated it and dreamed of traveling to distant lands. Eventually, he hitched a ride on a whaling ship, the Plymouth, operating out of Hawaii. While the ship was whaling off the coast of Hokkaido, MacDonald loaded a boat with 36 days of supplies and a small library and set off alone for Japan. Landing on Rishiri Island, he was discovered by the Ainu, Japan’s indigenous people. The Ainu were welcoming, but MacDonald was disappointed they failed to live up to his expectations, branding them “uncouth and wild” compared to the “clean, refined and cultivated” Japanese. Probably getting tired of such judgmental statements, the Ainu eventually handed MacDonald over to the Japanese authorities. The Japanese were intrigued by MacDonald, as his Native American appearance resembled the Japanese, and his bag of textbooks gave his captors a positive impression of him. His immediate interest in writing down the details of the Japanese language led him to quickly make friends with his jailers. After a visit to the capital, he was sent to Nagasaki, where he was held captive in a small temple and taught English to Japanese interpreters. In 1849, the USS Preble warship arrived in Nagasaki looking for any stranded American sailors. The Japanese asked MacDonald to explain the US ranking system so they could meet the captain of the vessel with an official of appropriate rank. In the course of his explanation, MacDonald had to explain to the Japanese the concept of American democracy. MacDonald left with the Preble and ended up in the gold mines of Australia. He then continued to travel before settling in Washington to write his memoirs. The last words of the first American English teacher in Japan were to his niece: “Sayonara, my dear, sayonara.” David Tormsen is slightly more hygienic than his Viking ancestors.