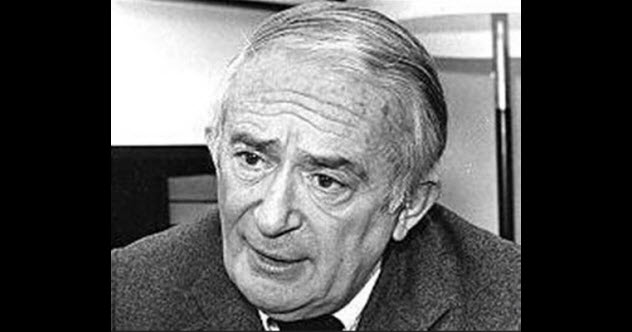

10 The Works Of Elmyr de Hory

During his lifetime, Elmyr de Hory was so famous as an art forger that his villa in Ibiza was a frequent stopover for the jet set, the same people who were duped into buying his fakes. De Hory was the subject of F for Fake, an Orson Welles film, and today, his forged paintings can sell for a great deal of money. Many museums still display his works because the curators believe that they were created by great masters. De Hory constantly moved from one city to another. Much of his early life is unknown, so all we have are the anecdotes that were told by de Hory. He was born in Hungary and claimed that his entire family was killed by the Nazis. In 1947, he made his way to New York City and found a way to pay for art lessons. His own paintings never sold well, but his detailed copies of other artists’ paintings sold quickly. De Hory always used period canvases to ensure the air of authenticity. De Hory and his associates escaped detection until 1967 when a huge scandal about fake art seemed to point to him. But the question remained: Why did it take so long for anyone to notice? It was his eye for detail that allowed de Hory to become so successful. Over the course of his career, he sold thousands of forgeries, including 100 to John Connally, the former governor of Texas. When de Hory began to live in a villa in Ibiza, he was visited by the likes of Marlene Dietrich, Orson Welles, and Clifford Irving (who wrote a biography about de Hory as well as a fake autobiography about Howard Hughes). After authorities pressed criminal charges against de Hory, he committed suicide in 1976 by taking an overdose of sleeping pills. Ironically, fakes by de Hory have become the subject of forgery themselves. Since a de Hory can sell for several thousand dollars, fake de Horys are big business.

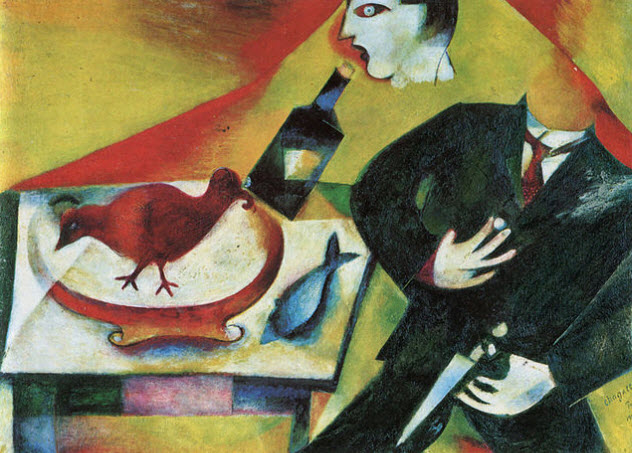

9 Ely Sakhai’s Unobserved Fakes

Ely Sakhai’s career as an art forger shone a light on the worst aspect of the art world: Many knew that there was something wrong with with his “originals,” but no one wanted to report the problem. As long as the paintings were passable and created by an artist who was famous enough, they could be sold as premium art pieces. This unscrupulous practice allowed Sakhai to become wealthy and live a lifestyle that he wasn’t able to afford otherwise. When he was caught, Sakhai was running a forgery operation worth millions of dollars from his Union Square front. After immigrating to America from Iran in the 1960s, Sakhai quickly established himself as a successful art dealer and prominent figure in the Iranian-American community. He regularly dealt with Japanese customers because it was easier to sell fakes to them. Sakhai made huge amounts of money—as much as $3.5 million—and increasingly turned to more prestigious pieces as a dealer. One of his more premium paintings was by French Impressionist Marc Chagall, which sold for over $300,000 at auction in 1990. However, something odd was going on. Just three years later, Sakhai had sold the same Chagall to a Japanese businessman for over $500,000. The FBI began to investigate and realized that art dealer Ely Sakhai was simply producing fakes. His scheme was to buy cheaper, lesser-known paintings by prominent artists and then sell his own versions to an unsuspecting public. He would copy certificates of authenticity and “issue” them for his fakes. Apparently, this worked well because he wasn’t caught until 2004. However, one question still plagues law enforcement: Who painted the fakes? Sakhai was not an artist, so whom did he know? To this day, the question remains unanswered.

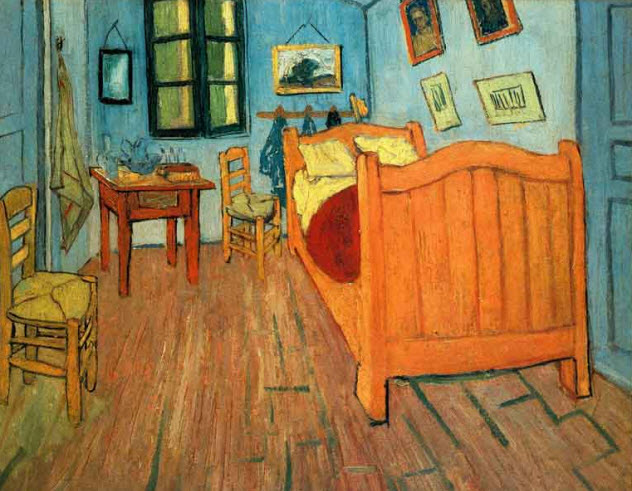

8 The Wacker Case

Today, Vincent van Gogh’s artwork is regularly auctioned for millions of dollars. He has been acclaimed as one of the world’s greatest artists. But his genius was recognized even at the turn of the 20th century. In fact, his paintings were so valuable that a German man named Otto Wacker was able to pull off a major scam involving van Gogh’s work in 1927. When Wacker claimed to have 33 van Goghs in his possession, dealers were quick to make offers. But there was just one problem: The paintings were fakes. Grete Ring and Walter Feilchenfeldt, the managers of the firm that bought the paintings, didn’t catch on at first. They had scheduled a major exhibition but had only received 29 of the paintings in time. So they were anxious for Wacker to deliver the remaining four pieces. When the four paintings finally arrived, Ring and Feilchenfeldt breathed sighs of relief. But upon examining the artwork, the managers realized that the paintings were definitely not van Gogh’s. Although they removed the fake paintings from the exhibition before their reputations were damaged, the managers were understandably angry about being bamboozled. Over the next five years, a parade of experts, curators, and dealers examined the paintings. In 1932, Wacker was convicted for his forgeries. It took so long because Wacker was on the cutting edge of forgers who used chemistry to achieve an authentic look. He also paid extreme attention to detail. Some of the paintings from Wacker were real van Goghs. But his fakes were so good that they couldn’t be identified even with the most rigorous testing of the time. The Wacker case caused dealers to upgrade their methods for combating increasingly sophisticated fraud.

7 Pei-Shen Qian And The Bergantinos Diaz Brothers

Pei-Shen Qian arrived in America in 1981. For much of the decade, he was a poor artist selling paintings on a street corner in Manhattan. He had started innocently enough. In his native country of China, he had painted portraits of Chairman Mao in art class. He probably never realized that he would be at the center of a multimillion-dollar art fraud scheme one day. It all began with Jose Carlos Bergantinos Diaz’s discovery of Pei-Shen Qian in the late 1980s. Qian’s pieces looked so authentic that Jose Carlos realized that they could make good money selling them. Working with Jose Carlos’s brother, Jesus Angel, the group was remarkably successful because Jose Carlos tried to keep the paintings looking as authentic as possible. He went to flea markets to buy old canvases and old paint. He put tea bags on new canvases to give them a vintage look. Pei-Shen Qian didn’t receive much of the millions that were made from his art. Throughout the 1990s, he was paid no more than a couple hundred dollars for each painting. By 2008, he was paid $7,000, but that was still a drop in the bucket. After getting the paintings from Pei-Shen Qian, the brothers had art dealer Glafira Rosales sell them. She sold the vast majority to the prestigious Knoedler & Company gallery. The big surprise is how long this went on. It wasn’t until Rosales confessed to the FBI that the scheme unraveled. The Bergantinos Diaz brothers were convicted along with Rosales. The only one who got away with it was Pei-Shen Qian. He laughed all the way back to China where extradition is rarely enforced. He said about the controversy: “The FBI said [the paintings] were done by the hands of a genius. [ . . . ] Well, that’s me. How strange it feels!”

6 The Stay-At-Home Fraudster John Myatt

Like so many others, John Myatt was a talented artist who couldn’t get his own works sold. In the 1980s, Myatt’s wife left him. The couple had two children, both of whom stayed with Myatt. This turn of events left him in a vulnerable state: How could he support his two children as a single parent? He turned to a lucrative industry—art forgery—which paid the bills and allowed him to be with his children. Myatt first entered the world of forgery when he put out an ad for legal forgeries that he painted for £250 each. One was good enough to catch the attention of John Drewe, an art dealer who became Myatt’s partner in crime. Myatt realized his first economic windfall when he sold an Albert Gleizes “original” for £25,000. “Twelve-and-a-half-thousand pounds [he split the proceeds with Drewe] means I can get a car that works and doesn’t break down all the time,” Myatt explained. For the next seven years, Myatt continued his lucrative charade. He sold over 200 paintings, some for as much as $150,000 each. However, Drewe’s behavior eventually became too erratic for Myatt and he dissolved the partnership. Later, Drewe’s ex-girlfriend spilled the beans. Drewe went to prison, and Myatt was convicted soon afterward in 1999. He admitted to creating 200 fakes, but only 80 have been recovered. Myatt has become a critic of the art industry: “The nonsense, really, is that paintings should be priced the way they are, that a van Gogh can go for, what is it, $75 million? That’s disgusting.” Since being released from prison, Myatt has found a new career in teaching fraudulent art recognition to Scotland Yard.

5 The Most Successful Art Forger In History

By all appearances, Wolfgang Beltracchi was nothing more than a wealthy hippie who knew the art world well. He lived in a $7 million villa in Freiburg, Germany, near the Black Forest. While the home was being constructed, he lived in the penthouse of the luxurious Colombi Hotel with his wife. Beltracchi could afford this lifestyle because he was perhaps the most successful art forger in history, according to experts. Watch this video on YouTube Throughout much of Beltracchi’s early life, he was just another restless hippie moving around places like Amsterdam and Morocco and doing drugs. His copying abilities seem to have manifested early, though. He once shocked his mother by painting a Picasso in a single day. He was self-taught, which is especially remarkable considering his ability to mimic a wide variety of styles. He has expertly copied Old Masters, surrealists, modernists, and just about every other type of painter in art history. Beltracchi’s career started innocently enough. One day, he saw that paintings of 18th-century winter landscapes were selling for low amounts but paintings with skaters in them sold for five times more. He bought the cheaper paintings, added skaters, and flipped them for a profit. The exact number of his fakes is unknown, but it must be staggering considering how long he operated without detection. The most prestigious auction houses in the world—like Sotheby’s and Christie’s—have sold his works for well into the six and seven figures. One of his paintings, a fake Max Ernst, sold for $7 million in 2006. Only 14 of his paintings were cited in the criminal case against him. But his total profit from just those 14 was a staggering $22 million.

4 The eBay Frauds

In 2001, Kenneth Walton, Scott Beach, and Kenneth Fetterman created 40 fake “shill” accounts on eBay and worked together to bid up the price of art that they were auctioning. They did this with over 1,100 pieces and made over $450,000. But they became greedy and almost sold a Richard Diebenkorn painting for more than $100,000. Even worse, it was fake. According to eBay policy, shilling—the practice of bidding on your own items to drive up the price—is banned. But the three men did it anyway by using multiple accounts. When they got greedy and decided to sell the fake Diebenkorn, their scheme crumbled. They weren’t even desperate for money. Kenneth Watson, a well-paid attorney, claimed that boredom propelled him to engage in illegal behavior for the thrill. One day, he bought an $8 painting at a junk shop. Seeing that the style was similar to that of obscure 20th-century artist Richard Diebenkorn, Watson grabbed a paintbrush and signed the canvas “RD52.” Diebenkorn’s work is highly collectible by the few people who are familiar with it. Watson created an elaborate backstory in which he portrayed himself as clueless about the painting. He said that his wife wouldn’t let him hang the painting in the house, so he kept it in the garage. Then Watson pretended that he had purchased the painting in Berkeley (where Diebenkorn produced much of his work). Watson also casually mentioned the signature. Of course, he wanted people to think that the painting was a Diebenkorn. His scheme worked. The bidding rose to $135,805 before eBay and the FBI stepped in. All three men were convicted for their parts in the crime. Even while he was under FBI investigation, Watson continued to sell phony art on eBay. As this was the first known case of high-dollar fraud on eBay, the company was forced to change their policies to curb the sale of forgeries on their site.

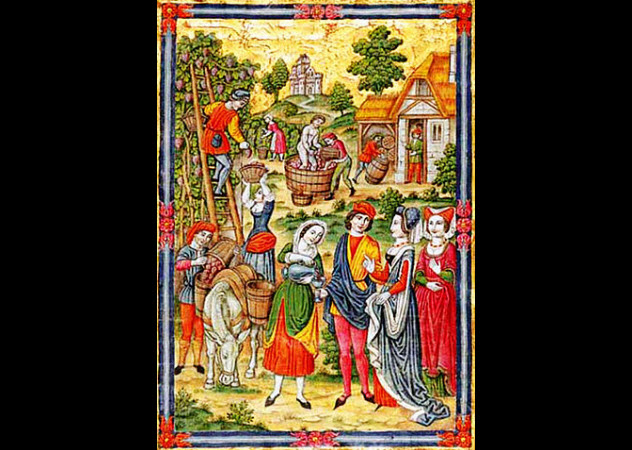

3 The Spanish Forger

Unlike the others on this list, the Spanish Forger was never caught. Everything about him remains an enigma: his identity, his motives, and even his ethnicity. His name proves nothing because he probably wasn’t Spanish. All of this demonstrates the Spanish Forger’s brilliance. No one knows how long he operated or how many fakes he produced in his lifetime. His case still boggles the mind to this day. In 1930, the Spanish Forger’s work was first recognized when Count Umberto Gnoli offered to sell a painting called The Betrothal of St. Ursula to the Metropolitan Museum for £30,000. Believing that the painting was created in 1450 by Maestro Jorge Inglese, Gnoli took it to Belle de Costa Greene, the first director of the Morgan Library, for authentication. However, Greene concluded that it was a fake. Since Ingles was a Spanish painter, the person who forged the work was dubbed the “Spanish Forger.” By 1978, William Voelkle, an associate curator at the Morgan Library, had gathered 150 fakes attributed to the Spanish Forger. It is generally believed that the Spanish Forger did most of his work around the turn of the 20th century. From 1869 to 1884, an illustrated, five-volume series on medieval artwork was published. Its popularity created a market for medieval artwork and served as source material for the Spanish Forger. Rather than copy the paintings outright, the Spanish Forger combined elements from various paintings to create something wholly original. Little mistakes such as a misunderstanding of chess, Latin, and liturgy exposed the Spanish Forger. Otherwise, he hid himself well and continues to remain unidentified.

2 The Fake Portrait Of Mary Todd Lincoln

For many years, an iconic portrait of Mary Todd Lincoln hung in the governor’s house in Springfield, Illinois. In 1864, it had been painted by respected portrait artist Francis Bicknell Carpenter as a gift from Mary Todd to her husband, Abraham Lincoln. But Lincoln was assassinated before his wife could present the painting to him. Such a valuable piece of history certainly belonged in a place like the governor’s home—except that it was a complete hoax. The descendants of Lincoln had discovered the painting in 1929, purchased it for a few thousand dollars, and donated it to the governor’s mansion in 1976. It hung there for 32 years until it was sent to a conservator for cleaning. The conservator discovered that the painting was actually a fraud perpetrated against the Lincoln family. It was a portrait of an unidentified subject that was painted by con man Lew Bloom. He altered the subject’s features to resemble those of Mary Todd Lincoln and then publicly presented the work as a portrait of her. According to Harold Holzer, a Lincoln historian, the brooch that Mary Todd wore in the portrait featured an 1857 photograph of Abraham Lincoln that she despised. She is also seen wearing a crucifix, a Catholic tradition that would have been at odds with Mary Todd’s Protestantism. After the fraud was uncovered, the portrait was removed from the Illinois governor’s mansion. It now hangs in the Lincoln Library with its true origins acknowledged.

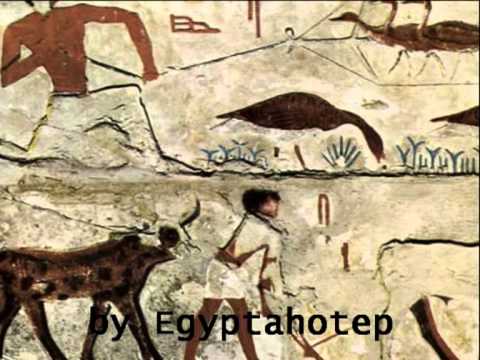

1 The Egyptian Mona Lisa

Meidum Geese is one of the most iconic paintings in Egypt and has been dubbed the Egyptian Mona Lisa. Discovered in the tomb of Pharaoh Nefermaat, it was supposedly painted between 2610 BC and 2590 BC. Meidum Geese was considered one of the greatest pieces of art from that era due to its high quality and level of detail. Since it was first uncovered in 1871 by Luigi Vassalli, it has been consistently heralded as an artistic masterpiece. Unfortunately, a recent examination determined that it is probably a hoax. Highly respected researcher Francesco Tiradritti, who is also director of the Italian archaeological mission in Egypt, studied the painting in person and from high-resolution photographs. After extensive examination, he said that there was overwhelming evidence that the painting was a fake. He believes that it was painted in 1871 by Luigi Vassalli himself. The first red flag was in the breeds of geese—the red-breasted goose and the bean goose—in the photograph. Both are tundra breeds that are unlikely to fly as far south as Egypt for the winter. Another issue concerns the use of colors. Beige isn’t seen in any other Egyptian work from that period. In addition, the painting used shades of red and orange that were not comparable to those in Atet’s chapel, where Vassalli allegedly found the painting. Vassalli was a learned scholar and an accomplished painter, so it was possible that he created the Meidum Geese. The most damning evidence comes from another painting recovered from Atet’s chapel. It depicts a vulture and a basket. To us, this means nothing. But to an expert Egyptologist like Vassalli, it represents the letters “G” and “A”—the monogram of his second wife, Gigliati Angiola. Gordon Gora is a struggling author who is desperately trying to make it. He is working on several projects, but until he finishes one, he will write for Listverse for his bread and butter. You can write him at [email protected].