10Who Killed Jon Parr?

John Parr was likely one of the first—if not the first—British citizen to be killed during World War I, but no one really knows what happened to him. The young man from London was just 14 when he signed up to fight, lying about his age to join the military. His first deployment was to northern France in 1914, where his unit was one of those tasked with stopping the German advance through Belgium. But by the time his comrades engaged the German troops, Parr was already missing. Yet the British military would continue to claim he was alive for for several months, before belatedly recognizing his death in 1915. Parr was a member of the reconnaissance team, who rode bicycles through the war-torn countryside to deliver messages. During the buildup to the Battle of Mons, the first major British engagement of the war, one of his companions said that they ran into a German unit and Parr was killed, a story that was supported by an eight-year-old Belgian girl. His body was said to have been recovered and buried by the Germans, but military and war researchers say that the skirmish could not have happened as Parr’s companion described it. The Germans were still well outside the area where the messengers would have been riding, and there are no records of the encounter in British or German files, diaries, or journals. That leaves open the possibility that the 14-year-old soldier was killed by friendly fire (perhaps unfamiliar British and Belgian troops mistook each other for Germans), but the manner of his death will probably never be known for certain. Parr’s distraught mother wrote letter after letter to the British military in an attempt to get some closure about her son’s fate. It never came.

9The Lost Treasure Of The Tsars

As World War I wore on, Russia was having its own problems on the home front—problems that would ultimately lead to the execution of their royal family. As internal and external threats loomed, it was decided that a huge portion—up to 73 percent—of the country’s gold reserves should be moved to the interior for safety. The gold was first sent from Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) to Kazan, and from there it was scattered even further. Just where, no one’s quite sure. According to some, the gold was seized by Admiral Alexander Kolchak, who spent all or part of it in his doomed war against Lenin’s forces. Others claim that there’s a series of secret gold vaults, long since lost, scattered across Siberia. Yet another theory holds that the entire treasure was simply buried in the forests near Kazan. The town of Omsk, once Kolchak’s capital and supposedly sitting on top of a labyrinth of tunnels, is a favorite for the gold’s final resting place. Or maybe it was sunk to the bottom of Lake Baikal or buried near the village of Zakhlamino. There’s no shortage of theories—rumor holds that the men who buried the gold were immediately executed , making sure the hiding place would remain a secret. No one knows whether the theories are true or whether the gold might still be out there, hidden away somewhere in the vast wastes of Siberia.

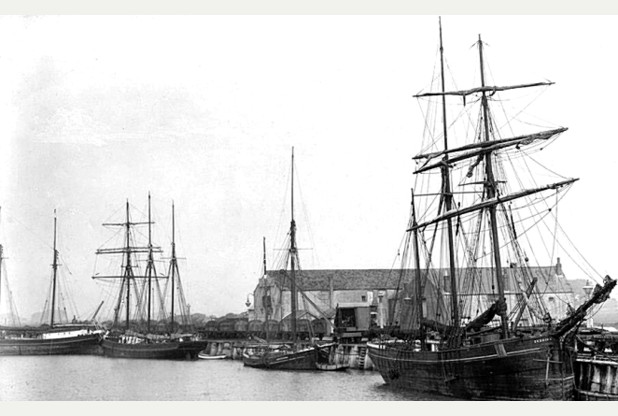

8What Happened To The Crew Of The Zebrina?

The Zebrina was a flat-bottomed schooner built in 1873. She was passed around among owners until her odd fate in 1917, when she was being used to haul coal between Cornwall and France, a trip that should have taken about 30 hours. On September 17, she was found beached on Rozel Point in France—with no crew. According to the French coast guard, the ship was completely undamaged. The table was set, there was nothing amiss in the captain’s log—the only sign that anything was slightly wrong, aside from the missing crew, was some slightly tangled sails. There are a couple of different theories about what happened to the sailors. One suggests that the Zebrina was caught in a storm and the entire crew were washed overboard as they attempted to secure everything on the deck. But this seems unlikely, given that the Zebrina was found in such a spotless condition. Others had suggested that the Zebrina had fallen victim to the German U-boats that roamed the English Channel targeting supply ships. But she wasn’t torpedoed and all her log books were found intact. German commanders usually seized the logs of the ships they destroyed as proof. But it has also been suggested that the Zebrina was much, much more than a simple transport ship. Records found by local historians indicate that there were 23 people on board, instead of the usual crew of six. That suggests that the Zebrina might have been a Q-boat—a merchant ship armed to the teeth with the goal of luring unsuspecting U-boats into a skirmish. Because of her flat bottom, the Zebrina would have been extremely difficult to torpedo, making her perfect for work as a Q-boat. But perhaps something went wrong and a pursuing U-boat gained the upper hand, boarding the Zebrina and seizing the crew—then never made it home. It’s an intriguing theory, but unfortunately simply guesswork. As things stand, it’s unlikely the mystery of World War I’s ghost ship will ever be solved.

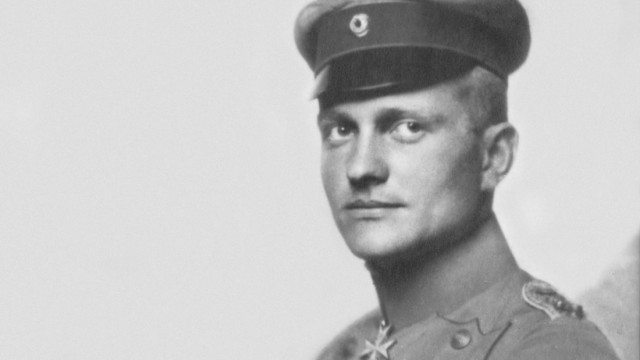

7Who Killed The Red Baron?

The Red Baron is perhaps the most famous pilot in history—even those who don’t know anything about military history have heard of him. With 80 confirmed kills (including 21 in April 1917 alone), Manfred von Richthofen became not only a target, but the face of the enemy for Allied troops. The Red Baron was finally shot down on April 21, 1918, but it’s never been exactly clear how. His body was recovered by Allied troops in France and he was given a military burial with full honors, but at the same time they were honoring their fallen enemy, people were scrambling to take credit for his death. Even today, theories abound as to who fired the shots that brought the Red Baron down. A squadron from the Australian Flying Corps claimed to have engaged the Baron, but it’s now thought that they were actually up against other planes from his unit. It’s also been suggested that the fatal shots didn’t come from a plane at all, but from the ground—and there are even different versions of that story. Some say that it was an Australian anti-aircraft battery, others say it was an anonymous rifleman, and still others claim it was a ground-based machine gun crew. The official credit was given to the Canadian Captain Roy Brown of the RAF’s No. 209 Squadron, but critics say that his account is rather lacking in detail and eyewitness accounts seem to indicate that his encounter with the Baron came before his famous red plane was actually shot down.

6Who Was The Woman In The Uniform?

Fairly recently, a series of World War I photographs surfaced in northern France. Clearly private photos, several show a young lieutenant wearing a uniform from New Zealand. Another photo shows another New Zealander (a lieutenant in some of the photos, and later a captain) with a woman perched on his knee—the same person dressed in the lieutenant’s uniform in the first photos. The building in the background is the Villa des Acacias in France and the second man is Captain Albert Arthur Chapman, an Australian serving in the New Zealand Pioneer (Maori) Battalion. However, the woman has never been identified—and the pictures bring up some interesting questions. The first, of course, is who is she? Historians have speculated that she was a local Frenchwoman. The pictures suggest a romantic relationship, although Chapman returned home after the war alone and unmarried and the woman is clearly wearing a wedding ring. Alternatively, she may have been a friend, the wife of another soldier, or a family member. It was initially speculated that the uniform might belong to her, making her one of the first female officers in the military, but that’s since been debunked—there were no women officers in the British or New Zealand armies during the war. Based on Chapman’s appearance in the photos and his progression through the ranks, he knew her for at least two years. Their affection for each other is clear. Are the photos lonely mementos of an ill-fated love story? Did she survive the war, or could she have been struck down by the terrible Spanish Flu epidemic that followed it? Did she have a husband standing just outside the frame? Did Chapman’s solitary return to New Zealand after the war mean heartbreak or tragedy? Records indicate that he apparently never married, making this an extremely intimate, personal look at the lives touched by the war.

5Who Was Nurse Margaret Maule?

The overwhelming casualty figures of the World Wars make it easy to forget that each death represents a tragic personal story. Nurse Margaret Maule’s story has recently been uncovered, along with her suitcase, found tucked away in a cupboard at Abertay University. But the suitcase has yielded as many questions as answers, and the university has appealed to the public to help find the solution. They have no record of anyone named Margaret Maule ever being associated with the university, and no idea where the suitcase came from or who she really was. Documents in the suitcase include Maule’s diary, begun in 1914. Her brother was killed in the war and she initially questioned the necessity of tending to wounded German soldiers alongside her own countrymen. But the diary also shows a fascinating evolution in her attitude. Tucked into the suitcase was also an autograph book, signed by the men whose lives she helped to save. Many were from German soldiers. It’s known that Maule worked in Dartford War Hospital in Kent and the Shakespeare Hospital in Glasgow, but much, much more information is needed before a complete picture of her life—and the lives of the nurses that worked alongside her—can be pieced together.

4Who Fired The First Shot?

The earliest claim for the dubious honor of being the first to fire came on July 29, when Austro-Hungarian navy vessels on the River Sava opened fire on Belgrade. The shots that started it all were fired by the Austro-Hungarian gunboat Bodrog, which still sits on the River Danube, now a forgotten, rusting hulk. But in Britain, the situation is less clear. According to British military tradition, the first shot was fired on August 22, 1914, by Corporal E. Thomas, a cavalry drummer. Thomas was part of a recon patrol tasked with monitoring the movements of German troops in Belgium. He and his squad ran into four German cavalrymen, an old-fashioned cavalry charge ensued, and the first shot was fired. Evidently, no one was killed in the skirmish. An even earlier contender came on August 12, 1914, when Alhaji Grunshi, a West African soldier in the British army, fired on German forces protecting one of their greatest technological assets—a wireless communication station in Togo capable of sending transmissions as far afield as Asia. When war was declared, the German colony in Togo came under immediate attack from the surrounding British territories, making a strong claim for the first British shots of the war. But the Australians also lay claim to being the first to fire in the name of the British Empire. On August 5, 1914, John Purdue was an artillery sergeant stationed at Fort Nepean, just south of Melbourne. He and his crew fired on the German merchant vessel the SS Pfalz, forcing it to surrender.

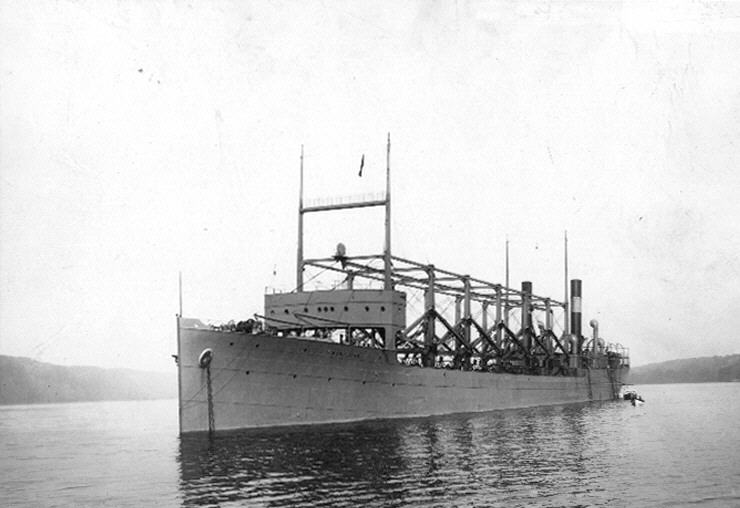

3What Happened To The USS Cyclops?

The loss of the USS Cyclops was, at the time, the largest loss of life the United States Navy had ever seen in a single incident. And it’s still not exactly clear what happened. In 1918, the Cyclops, a truly one-of-a-kind ship, was part of the Naval Overseas Transportation Service, shuttling cargo back and forth from Brazil. On February 15, 1918, she left Rio de Janeiro loaded with almost 11,000 tons of manganese ore destined for Baltimore, Maryland. On March 3, the captain re-routed her to Barbados, reporting problems with the starboard engine. At the time, it was suggested both that she was carrying too much cargo and that she needed repairs. She left for the States the next day. It was the last time she was ever seen. In addition to her cargo, there were 309 people on board the Cyclops when she disappeared. Originally due into Baltimore on March 13, there were several reported sightings of the ship off the American coast, but they are all now thought rather doubtful. There are plenty of theories about what happened to the ship, including a combination of preexisting hull problems and defective engines. Or perhaps the weight caused slow flooding, or the cargo, loaded by an inexperienced crew, suddenly shifted and caused the ship to capsize. Until the wreck is found, it is unlikely we will get any answers.

2Who Was the Artist JM?

In a time before photojournalism was widespread, soldiers’ artwork was one of the only true depictions of life on the front line. Recently, professors at the University of Victoria in Canada found an incredible book of World War I sketches—and they have no idea who created them. Aside from his amazing talent, little is known about the mysterious artist. The work is on the stationery of the Royal Regiment of Artillery and signed with the initials “J.M.” The artist was probably based in France and/or Belgium between 1917 and 1918. Some of the art is inscribed to his daughter, Adele. He survived the war, as one of the pieces is dated 1920. There are two books of sketches, done in pen and ink as well as in watercolor. They’re a breathtakingly beautiful look at not only war, but into the mind of a soul trapped in the middle of it. Devils and skeletons dance around a king wearing a crown, terrified horses flee from dropping bombs and die from gas poured into the trenches. He illustrates towns destroyed by conflict—the eerie, peaceful images of graves, exhausted nurses, and smoking rubble. The university is still hopeful that they’re going to find the mysterious, talented artist who created this very, very personal look into the horrors of war.

1What Happened To Bela Kiss?

When Bela Kiss was called into service in 1914, the villagers he left behind thought of him as an incredibly intelligent, well-liked, friendly sort of fellow, who was known as being something of a ladies’ man. Kiss lived in a small house in the Hungarian town of Cintoka and when his landlord heard a rumor that he had met with a tragic wartime fate abroad, he sadly went to clean out the house before putting it up for rent again. That was when he found the bodies. The metal drums Kiss had claimed to be stockpiling fuel in were actually full of the bodies of his victims, all women but for one, and all preserved in alcohol. Further investigation revealed that Kiss was luring women to him with promises of love and marriage, then murdering them for his own financial gain. He found many of his victims through ads placed in the Budapest newspapers—the lonely hearts ads weren’t just looking for women, they were looking for women with a certain financial standing. And they came, including one woman who sold her successful dressmaking business before she met her end in one of Kiss’s metal barrels. Kiss was still away at the front—and very much alive—when the bodies of his victims were discovered, and the fog of war allowed him to slip away. Conflicting reports of his fate came pouring in. Some claimed that he had died after contracting typhoid, others said he had been arrested and jailed on burglary charges, while others maintained it was yellow fever that had finally killed him in Turkey. Authorities only got close to him once, when they received word he was in a hospital recovering from a wound, but by the time they got there Kiss had switched a dead man’s body for his own and fled. In the chaos of the the war, it was impossible to track him. There were reports that he had joined the French Foreign Legion and Kiss sightings were happening as far away as New York City even into the 1930s. In 1936, a city janitor was even targeted as being Kiss, but by the time authorities got there to check him out, he was already gone. No other murders were ever attributed to him, but that certainly doesn’t mean there weren’t any. Read More: Twitter