10 Patience Wright And The US Founding Fathers

Patience Wright was born in New York in 1725, and she had a rather unusual talent. She was an artist, but she worked in wax and had the rather impressive skill of being able to fashion incredibly lifelike figures. She did it all without looking, as well. Because wax had to be kept warm and pliable, her normal method was to shape the heads beneath her skirts before revealing the final product. Married and widowed, she eventually turned to her wax figures as a source of income. After a random meeting (on the sort that usually only happens in tall tales) with Benjamin Franklin’s sister, she was heading to England to impress the Brits with her art. Her work was incredibly sought after, and her colonial charm ensured she was going to go far; it wasn’t long before she was modeling the heads of nobility and, eventually, King George III himself. While she sculpted, she listened. She began sending court secrets back to anyone in the colonies who she thought would truly appreciate them, and Benjamin Franklin was one of her favorite recipients. She was better at sculpting than she was at spying, though, and although no formal charges had been brought against her, she disappeared from the English court scene when the American Revolution started. She sent letters upon letters to Franklin, advising him on just what his next steps should be. From befriending the poor living in England to supporting a rebellion against the monarchy on English soil, her letters didn’t just go unheeded, they went ignored. She fashioned more busts of Franklin (hiding more secrets inside, before she sent them to him), and begged for an audience with George Washington—presumably to shape his wax figure. She offered any and all services to Thomas Jefferson, in hopes of getting a response that never came. At one point, Abigail Adams likened her to the “Queen of sluts.” Her desired audiences never came, and by the time she died, she had fallen so far out of favor that the Continental Congress refused to help her sister pay for her burial. Only one of her wax figures has survived—a figure of William Pitt, now kept in Westminster Abbey.

9 Lady Georgina Fane And The Duke of Wellington

The Duke of Wellington is one of the most celebrated military heroes in British history, but the man who triumphed over the armies of Napoleon was once forced to ask Georgina Fane’s mother to please, please, please have her stop harassing him. The two first met in 1815 at a dance not long after the Battle of Waterloo. Wellington was married, but their relationship soon turned into something that was much more than dancing. It continued for some time, and when Wellington’s wife passed away in 1830, Fane saw her chance to be Mrs. Wellington. Wellington ended their affair, but Fane persisted. The 29-year-old lady was clearly not going to just give up and let the Duke choose someone else to be his next wife, and she plagued him with daily letters and threats that she would sue him for breach of contract. According to Lady Fane, he had promised to marry her, and she had the love letters to prove it. Wellington, on the other hand, maintained that he had never said anything of the sort and, in a very gentlemanly manner, suggested that she had been incredibly mistaken. Wellington’s attempts at appealing to Georgina’s mother for help in getting her to stop have only recently been found. He was 82 at the time, and the angrily written letter to the Countess Dowager of Westmoreland describes the girl’s behavior as specifically designed “to injure, to vex and torment.” He acknowledges that there were letters that had passed between them, and part of his complaints include her seemingly shameless broadcasting of the contents of the very private letters to other parties.

8 Lady Caroline Lamb And Lord Byron

According to family documents, the young Lady Caroline was such an irritable, emotional, slightly mad child that no one really wanted to have that much to do with her. The relative isolation of her childhood probably didn’t do much to help her get rid of whatever issues she’d developed before she was even a teenager. She was married in 1805 (and had a son who suffered with mental health issues for most of his life), but being married certainly didn’t stop her from becoming absolutely obsessed with Lord Byron. They met in 1812, and when she played the aloof, uninterested woman in a sea of swarming admirers, she got his attention. Accounts vary; many say that they had a relationship that was at first consensual in every way, but the whole thing soon turned scandalous, and her husband decided that distance was probably the best thing. The following few years saw nothing short of a complete emotional breakdown for Lady Lamb. She tried cutting herself, burning Byron’s effigy, forging letters to get pictures of him, and impersonating a servant to gain access to him. By this time, he was already married; when ignoring her didn’t work, he tried sending some very direct, to-the-point letters. She became well-known for temper tantrums, her drinking, and, weirdly, her novels. Her first, Glenarvon, was deemed by critics to be little more than unreadable. It’s the story of a scandalous, torrid affair, and it’s a really, really, bad attempt at disguising a fictional account of her own relationship with Byron. Even as she was being threatened by those who wanted to have her committed, she wrote a handful of songs, some poems that were eerie, mocking parodies of Byron’s work, and three novels that were clear attempts at taking over and impersonating the career that Byron was quite successfully doing elsewhere.

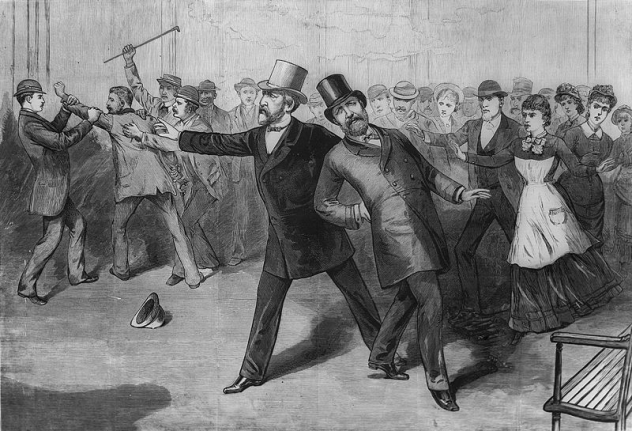

7 Richard Lawrence And Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson has the reputation as being one of the toughest presidents that the US has ever had, and on January 30, 1835, he personally thwarted an assassination attempt. When Richard Lawrence drew a couple of pistols (they both misfired) and attempted to kill the president, Jackson pulled out his cane and started swinging. Jackson was taken back to the White House, and a bizarre saga started to unfold around his would-be assassin. Lawrence was an unemployed painter whose first claim was that Jackson had killed his father. While that was quickly found not to be true, more and more started to come out about the man. Lawrence, under continued questioning, revealed that he thought he was actually King Richard III of England, and that he had been stalking the president because of Jackson’s veto of a bill that would have reinstated the Second Bank of the United States. With the charter fallen by the wayside, Lawrence was convinced that he had been all but cheated out of receiving a dispensation for his personally owned estates. He was put on trial for the attempted murder of the president in spite of his continued protests that the King shouldn’t be judged by a group of commoners. He dressed and acted the part in court, and, eventually, he was found not guilty due to insanity. He died in 1861, after spending his remaining years in an asylum.

6 Adele Hugo And Albert Pinson

Adele Hugo was the youngest child of Victor Hugo. Born in 1830, she spent much of her young life surrounded by her father’s famous friends and listening in on some of the great intellectual and literary conversations of the day, recording pretty much everything in her diaries. Things started to change for her with the loss of her sister, Leopoldine, and with a series of seances that were held in the house starting when she was around 23 years old. Signs of mental illness went unnoticed even though it was already known to run in her family. While living on the Channel Islands, she met a naval officer named Albert Pinson. By all accounts, he was an angry, ill-mannered, and pretty unfaithful man, but she fell in love with him anyway. By 1861, he was transferred to Halifax, but her obsession with him continued. She began insisting that they were to be married and eventually ran away from home to join him. Pinson kept insisting that he wanted nothing to do with her, but that didn’t keep her from renting rooms near him, following him around, and peering through his windows at night. All the while, she recorded her feelings and activities in her diaries. She remained in Halifax for several years, following him next to Barbados. By then, her money was gone, and she was reduced to living on the streets, still following in his footsteps, hoping for a reconciliation and a return on her love. It wasn’t to happen, though, and eventually she was returned to Paris and to the custody of her father. There, she was committed to a mental institution and lived to be 85 years old.

5 Jane Bigelow And Charles Dickens

When Charles Dickens went on a massive tour of the US stage from 1867–68, his readings were a must-see. Newspapers reported absolutely everything about him, from commenting on what he was wearing to what condiments he did, or didn’t, put on his food when he was going out to eat. He was a larger-than-life celebrity, and he also attracted a notable stalker. Jane Bigelow was married to the editor of the New York Evening Post when Dickens came to town. John Bigelow, who would also go on to have a storied political career, did it all in spite of his wife rather than with her support. They had nine children, but it’s uncertain as to whether or not that made up for her rather undignified behavior—like once greeting the Prince of Wales with a slap on the back. The Bigelows met Dickens at the beginning of his US tour, and it wasn’t long before her nonexistent manners and grating attitude started to wear on him. He got along quite well with her husband, though, understanding exactly where the poor man was coming from. Dickens was famously not content with his own wife: Despite bearing him 10 children, he often referred to her as “embarrassing.” Jane Bigelow, however, was enamored of the British writer, and her exploits were recorded in the diary of the wife of Dickens’s publisher. Things truly came to a head when Dickens agreed to meet personally with one of his fans, a widow named Mrs. Hertz. The infamous Mrs. Bigelow, apparently outraged that the widow would dare to enter the private rooms of Dickens unescorted, was waiting outside for her when she emerged, descending on her and unashamedly hitting her. After that, Dickens took to tasking lookouts to keep an eye out for the woman, who kept trying to impose her company on him. They were specifically ordered to keep her away, although he ended up having to post guards at his hotel room to keep away the fans that were trying to get up close and personal with their favorite celebrity.

4 Charles Guiteau And James Garfield

James Garfield has the dubious distinction of being one of the shortest-serving US presidents, holding office for only 200 days before his assassination at the hands of the mentally unstable failed lawyer, Charles Guiteau. Guiteau’s obsession with Garfield started even before the latter was elected as president and is a pretty convoluted story. Having already failed at law, largely because of accusations that he was accepting clients for bill collecting, then keeping the money for himself, he decided to try his hand at politics. He originally supported Ulysses S. Grant; when Garfield took the Republican nomination, he changed his speeches and started speaking. When Garfield won, Guiteau believed that it was largely because of his efforts and began writing letters to the President requesting positions, first in Austria and then in Paris. When Garfield never responded, he became disillusioned and believed that Garfield was far, far from the savior he’d thought he was going to be. Guiteau became convinced that Garfield was tearing the country apart, and he needed to go. After settling on a gun, a weapon that would allow him to get up close and personal without the risk of harming anyone else, Guiteau stalked Garfield for some time before he would actually get the chance to kill him. He lingered outside the White House reading newspapers, and he followed Garfield to church and to the train station. It was at the station that his hand was stayed by the sight of Garfield’s wife, who was recovering from an illness. He’d later say that he hadn’t killed the President then, for he knew that it would have killed her, too, and he didn’t want to do that. He watched Garfield from across the street, cursing the innocent bystanders that wandered by. Finally, sick of losing his nerve, he mailed a few letters to the White House with his condolences on the President’s death, saying that it was something that had to be done for the good of the country. He finally shot Garfield not long afterward, inflicting what would have been a nonfatal bullet wound had doctors known that their unwashed hands, rooting around inside Garfield’s abdomen, were causing the infection that would eventually kill him. Guiteau’s fate was exactly what he’d foretold; he was found guilty of murder and hanged.

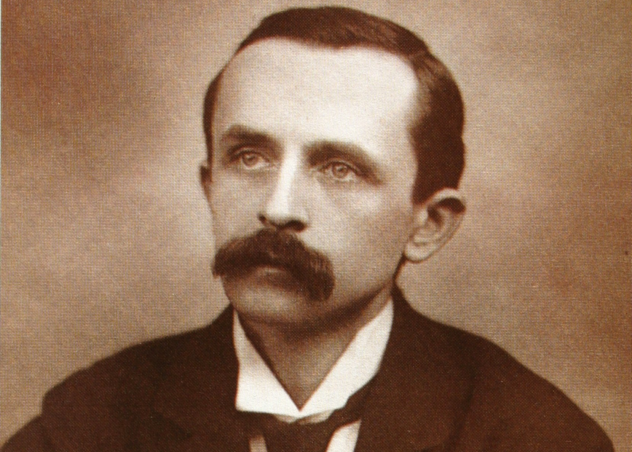

3 J.M. Barrie And The Children

This is a pretty nontraditional one, in that it’s not going to get creepy or weird—well, perhaps unsettling at the most and sad for certain. A little background context is needed. Born in 1860, Barrie, the author of Peter Pan, grew up in the shadow of an older brother, who died in a skating accident at 14. His mother consoled herself that her son, David, would never grow old, clearly an inspiration for Peter Pan. Barrie himself married but never had children of his own, although he adored them. Those pieces of the puzzle are absolutely necessary to see the whole picture: of the man who wrote Peter Pan as a novel originally titled, “The Boy Who Hated Mothers.” The name “Peter” comes from one of the five boys that Barrie combined to create the character. Of the boys, he wrote, “I always knew I made Peter by rubbing the five of you violently together.” He met the family first in 1898, as a four- and five-year-old pair of brothers walking with a nanny in Hyde Park were drawn to Barrie and his dog, a massive St. Bernard. Gradually, Barrie would meet their parents, Sylvia Llewellyn Davies her husband, Arthur. As the years progressed, they took vacations together and spent time in the country, and Barrie became an uncle to the boys. They would play at being pirates, tell stories, and share adventures—all the things that he would want to do with his own sons that he would never have. Both Arthur and Sylvia died young, which is where the unsettling bit of stalker behavior comes in. In her will, Sylvia wrote that she would like Jenny and Mary to take the boys. Jenny was their longtime nanny, and Mary was her sister. Barrie got a hold of the document first, though, changing the handwritten document from “Jenny” to “Jimmy.” Mary was, conveniently, his wife’s name, making it seem like Sylvia had wanted nothing more than the affectionately-called “Uncle” to become the guardian of her children. He got his wish. Letters written later from one of the five boys, Peter, would recall how Barrie took them away from their parents’ home, the friends they had known, and everything that was familiar. He remembers the whole thing as eerie and macabre, but he also remembers his guardian and uncle with incredible admiration, in spite of Barrie’s actions.

2 Alexander Main And George Eliot

It started out with a pretty short letter and a polite inquiry to an author about the right way to say one of the names in a book. George Eliot, insecure about her work as many writers are, responded; it started a cascade of longer and longer letters from Alexander Main. Her publisher came to refer to him as “The Gusher” due to the profuse and over-the-top nature of his letters. Eliot, though, was known for something well beyond the usual self-doubt of a writer; for her, it was nearly incapacitating. The letters—which called her “sublime” and assured her that those who read her works in the generations to come would be so, so grateful that she had lived to write—were exactly what she needed, and it wasn’t uncommon for their sentiment to be so powerful that they would move her to tears. The correspondence continued, and Main pushed to get closer and closer to Eliot, from a distance. He asked for permission to take her works and compile a list of selected quotes, packaging them into a single book of stand-alone bits of what he saw as the wisdom of the world. She and her publisher agreed, and it led to some of the strangest letters of all. The book was called Wide, Witty and Tender Sayings, and while Main was compiling, he was extraordinarily graphic about what he was doing. He wrote to her, “But here I am clipping and slashing great gashes out of writings every line of which I hold sacred, and finding a delight almost fiendish in the work of destruction.” Then there was, “Had anybody told me a few weeks ago that I should live to cut up George Eliot’s works, and not only so, but to take pleasure in the operation, I fear I should have knocked him down.” The weird, violent adoration in the letters was clear, and at the same time, Main himself remained something of an enigma to her. Every time she would inquire about him personally, he would give only the vaguest of answers, adding to the weird mystery around him. The result of his works is a pretty odd thing. As worshipful as his letters are and as weirdly cryptic as his choice of quotes can be, it’s his compilation that’s credited with keeping her work popular past her own generation.

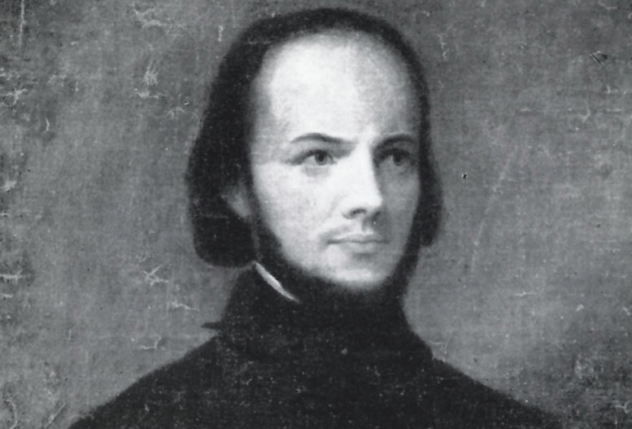

1 Rufus Griswold And Edgar Allan Poe

Harassment, defamation of character, and absolutely relentless fixation sometimes even continue after the target is dead. Today, we think of Edgar Allan Poe as a tortured genius, undoubtedly a drunkard, and probably a drug addict whose lack of self-control ultimately led to his death. That’s not entirely true, though, and most of Poe’s enduring image has been courtesy of a man who had a weird, one-sided rivalry with Poe in life. According to the story, it started when Poe won the heart and affections of a young widow named Frances Osgood. Even though he was married, Poe’s involvement with her was the stuff of romantic fairy tales, right down to the love letters. Griswold also had his eye on the young widow, though, and he didn’t take lightly to being interfered with by a man that he already didn’t like. In 1841, Griswold assembled an anthology of poetry; Poe reviewed it, critically, setting off some bad blood. Things just went downhill from there. Griswold bizarrely ended up being appointed executor to Poe’s will. (Some sources say it was Poe himself who asked Griswold; others claim that it was Poe’s mother-in-law who asked him.) Either way, the gloves came off. Griswold had unprecedented access to Poe’s estate and began a campaign of doctoring letters, writing some less-than-glamorous obituaries about him, and even releasing some completely and utterly slanderous biographies. He forged entire letters and wrote what he claimed to be the true story of Poe’s life and history, publishing it along with a collection of his works. He claimed Poe spent much of his career destitute and unable to truly make a living with his writing. He claimed there were gambling problems, alcoholism, and habitual opium use. Griswold wrote about Poe deserting the US Army, painting him as one of the worst kind of degenerates that he could come up with. Others soon jumped on Griswold’s interpretations of Poe’s life, citing his works as sure signs that it must all be true. Who but a failure, alcoholic, and opium addict could possibly write such dark stuff, after all? Griswold’s obsession with rewriting Poe’s history was such that even today, we’re not sure what’s true and what’s not. Most recently, it’s been found that Poe’s problems with alcohol were more along the lines of having no tolerance for it rather than drinking too much of it, and there’s no real evidence of his so-called opium addiction. Slowly, his reputation is being reclaimed from the angry, obsessed stalker that wouldn’t leave him alone even in death. Read More: Twitter