We seem equally fascinated by the idea of humans transforming into animals, or therianthropy. The transformation scene from An American Werewolf in London remains an iconic depiction of this otherworldly change. Such horror reminds us of our own animalistic roots. In modern times, most cultures see shape-shifting and therianthropy as the work of overactive imaginations or the remnants of a superstitious past. But, as some of the entries in this list will show, shape-shifting demons and witch therianthropes are not quite in the rearview mirrors of all cultures.

10 Tanuki

Go to Japan, and you will find the landscape peppered with statues of creatures baring inordinately large testicles. These ceramic sculptures are depictions of the tanuki—small, raccoon-like animals that are common to Japanese folklore. (Actual Japanese raccoon dogs are also referred to as tanuki.) Japanese legend speaks of a tile-maker who was made wealthy from a dancing tea kettle. The kettle was said to be a shape-shifting creature called a tanuki. These mythical beings were raccoon dogs that used their shape-shifting abilities to reward the kindly acts of strangers. The tale begins with a Shinto priest repairing an old tea kettle. He places the kettle, now spick and span, on a hot stove. The priest is horrified when, all of a sudden, the object sprouts arms and legs. “Ouch!” cries the tanuki. Thinking the kettle is cursed, the priest gives it away to a local tile-maker. Now in the possession of a new master, the shape-shifter strikes a deal. It promises to serve as the man’s “dancing kettle” in exchange for his kindness and respect. Some tanuki are said to have a much darker side to them. In the tale of the “Farmer and the Badger,” a tanuki shape-shifter destroys a Japanese farmer’s rice field.[1] The farmer ensnares the mischievous animal and vows to turn it into tanuki soup. But the farmer’s wife takes pity on the tanuki and lets it escape. In an act of vengeance, the tanuki murders the woman and turns her into soup. The tanuki then transforms into the farmer’s wife and tries to make the farmer eat a bowl of his beloved’s delicious remains. The story gets stranger yet. An enraged rabbit—one of the farmer’s friends—takes exception to the horror show. The rabbit punishes the tanuki by playing a series of tricks on it. The rabbit hurls a bee’s nest on the tanuki, sets him on fire, and thwarts him in a boat race.

9 Changelings

It was once believed that fairies, elves, or witches would abduct human infants and replace them with their own sinister offspring. The original babies were either raised by the mythological creatures or handed over to the Devil as a sacrificial gift. While the changeling takes on the guise of a small child, there are obvious signs that a swap has taken place. Changelings were said to speak with greater wisdom than that expected of a normal child. They also liked to dance, drink, and eat. However, despite their insatiable appetite, the creatures often displayed stunted growth. Changelings are common to European folklore and may even have pre-Christian roots. The first documented case of a changeling was described by the Bishop of Paris William of Auvergne in 13th-century France: They say they are skinny and always wailing and such milk-drinkers that four nurse maids do not supply sufficient milk to feed one. These appear to have remained with their nurses for many years, and afterward to have flown away, or rather vanished.[2] The “brewery of eggshells” test was commonly used to confirm the presence of a changeling. The child was placed in front of a roaring fire. A series of eggshells were filled with water and set ablaze. The display was enough to impress the changeling, prompting it to exclaim: “I have seen the acorn before the oak: I have seen the egg before the white chicken: I have never seen the equal to this!” Parents who felt they were the victims of changeling swaps took extreme measures. It was thought the fairies would return the original baby if the changeling was harmed. This meant the “counterfeit children” were often burned, beaten, or starved. In reality, the “changeling” was probably just a sickly child. The parents were likely confusing simple childhood disorders like autism or birth defects like spina bifida with superstitious manifestations.

8 Pooka

A mythical fairy of Celtic folklore, the pooka is a dark-furred creature that assumes a variety of forms. The name stems from the Old Irish word for “goblin,” puca. Legend has it that the pooka have used their shape-shifting powers to change into cats, rabbits, horses, ravens, goats, goblins, and even humans. The pooka’s motives are usually unclear, demonstrating both malevolent and benevolent intentions. According to some folklorists, the pooka usually comes out to wreak havoc at night. These sly pranksters leave their mountaintop homes to roam the countryside, smashing fences and spoiling crops. Its most common form is reported to be that of a black horse with golden eyes. The horse gallops around remote areas looking for a suitable rider. Those who fail to answer the creature’s calls have no alternative but to watch as the horse destroys their earthly possessions. It is said that Ireland’s King Brian Boru once tamed the fabled beast. He leashed the pooka with a bridle made from its own tail.[3] The king rode the pooka until it was utterly exhausted. He made the creature promise to leave both Christians and Irishmen in peace. The pooka was given a slight concession, though. It was still permitted to play its devilish tricks on unsuspecting drunkards and evildoers. Pooka can, on occasion, show a more caring side. Some of the more superstitious parts of Ireland believe the pooka reveals prophecies and warns people about evil fairies. They also reward acts of kindness by helping out with manual labor.

7 Skinwalkers

Skinwalkers were once normal members of the Navajo and Ute tribes. But after embracing dark magic and witchcraft, these former tribesmen ended up traveling a very different path. The skinwalker cloaks itself in the skin of whatever animal it wishes to become. These therianthropes can become bears, wolves, owls, coyotes, and crows. According to Navajo mystics, the skinwalker takes on the properties of that animal. For example, a tribal shaman could change into a wolf to gain speed and agility. To become a skinwalker, a medicine man must commit an act of great evil, like killing a close family member or friend. These disgraced shamans are permanently exiled from Navajo life. They have become, in Navajo tongue, yee naaldlooshii : “With it, he goes on all fours.” Skinwalkers are often cast out because of necrophilia, murder, or grave robbery. They also play sadistic practical jokes on others. They plant dismembered fingers in homes to lure apparitions and chase frightened motorists in dead of night. But the skinwalker’s secret weapon appears to be “corpse powder.” The powder induces convulsions and causes the recipient’s tongue to drop out.[4] Because they possess such formidable knowledge of spiritual medicine, the Navajo people blame skinwalkers for death, disease, and famine.

6 Kumiho

Popularized in Korean folklore, the kumiho (aka gumiho) is a nine-tailed fox with a penchant for young men. The kumiho is actually a demon who tries to lure men to their deaths by shape-shifting into a seductive woman. The demon fox uses a magical stone to extract the soul of its besotted victim. In some versions of the story, the fox rips out the liver or heart. This can take place while the demon is engaging in sexual acts. In “The Jewel of the Fox’s Tongue,” a shape-shifting kumiho slays 99 schoolboys, siphoning off their human energy.[5] In accordance with similar tales of the kumiho, the fox needs to claim just one more soul to reach heaven. But she is bested by her final victim. The fox tries to take the boy’s energy by rolling an enchanted jewel (yeowu guseul ) over his mouth. He sees through the fox’s ploy and swallows the jewel. This grants him great wisdom. He sees no other option but to rally his fellow villagers and hunt down the deceitful kumiho. The Korean word for “fox,” yowu, has negative connotations. It is often used to describe women who are cunning and manipulative. Tales of the kumiho aim to promote Confucian principles, warning Korean women against engaging in sexual deviancy.

5 Nagual

The Aztecs believed that animal spirits were linked to each person’s life energy. The nature of this spirit was determined through the Mesoamerican calendar. Sorcerers who had the power to transform into animals, and were born on certain dates, were known as naguals. The Olmecs and the Maya thought naguals were stealthy night stalkers who drank the blood of innocent mortals. Other reports suggested they could control the weather and cast bizarre illusions. The historian Antonio de Herrera penned one of the earliest accounts of these mysterious figures. He argued that the Devil would assume the form of a “lion, tiger, coyote, lizard, snake, bird, or other animal” to con the Maya tribespeople of Cerquin, Honduras. Herrera spoke of a tribesman who, in a desperate bid to achieve the wealth of his ancestors, embraced nagualism. After performing a sacrificial ritual in which he laid waste to a dog or a fowl, the man slept. Talking spirit animals filled his dreams and delivered the following prophecy: On such a day go hunting and the first animal or bird you see will be my form, and I shall remain your companion and Nagual for all time.[6] It is likely this prophecy was the work of an intoxicating plant called peyote (peyotl ). Its hallucinogenic properties were often mistaken for supernatural divinations. In many parts of rural Mexico, the legend of the nagual lives on. Recent sightings suggest the beast has now taken on a more feral appearance, looking like a large dog or wolf. The naguals have been blamed for missing persons, stolen goods, damaged property, and dead livestock.

4 Madame Pele And The Hog Child

Madame Pele is an ancient deity who played a major role in shaping the Hawaiian Islands. It is no wonder, then, that Pele plays such a pivotal role in Hawaiian culture. Stores feature her memorabilia. The Hawaii Volcanoes National Park has a large painting of the goddess. And there is a volcanic rock formation called Pele’s Chair. The shape-shifting goddess is also known by the name Pelehonuamea, or “she who shapes the sacred land.” Locals claim they have seen their goddess in the form of a white dog or a beautiful woman. Legend has it that Madame Pele was born in Tahiti. She was forced to flee, however, after seducing her sister’s husband—a wise decision, considering that her sister was the goddess of the sea. The voyage took her to the islands of Hawaii, where she used a divining rod (pa`oa) to create a series of giant fire pits. These pits represent the region’s many volcanoes. Madame Pele eventually settled down in Hawaii and created the most active of the island’s volcanoes, Kilauea. Today’s volcanic activity is said to be more pronounced when Pele is angered. It is, therefore, not unusual for local islanders to leave offerings to ease her mood. In 2018, many locals celebrated the eruption of Kilauea. The event triggered a number of earthquakes and destroyed many homes. “My house was an offering for Pele,” explained retired schoolteacher Monica Devlin. “It’s an awe-inspiring process of destruction and creation and I was lucky to glimpse it.” The goddess was romantically pursued by another shape-shifter—the demigod Kamapua’a (aka the Hog Child).[7] Kamapua’a could transform into fish, plants, and a powerful human-hog hybrid. Madame Pele was repulsed by the Hog Child’s advances, attacking him with a torrent of fire. In the ensuing battle, Kamapua’a wielded an unstoppable army of hogs to defeat Pele and her relatives.

3 Ilimu

Horrifying accounts of a predatory demon have spread throughout parts of Africa. One of the Bantu tribes of Kenya, the Kikuyu, names this evil hunter the ilimu. Some tribe members say the ilimu takes on the form of a healthy man. Others claim he looks more like a deformed village elder, with one of his feet jutting from the back of his neck. According to Kenyan folklore, the ilimu is a flesh-eating terror that can shape-shift into a replica of another human. To do this, the ilimu must steal the target’s hair, nail clippings, or blood.[8] The demon can also possess a range of animals, most often lions. Some African tribes attribute lion attacks to ilimu activity, consulting medicine men for solutions. In 1898, the British Empire coordinated the construction of a railway bridge over the Tsavo River. A large camp was established near the site to accommodate thousands of Indian workers. This served as an ideal hunting ground for a pair of highly intelligent lions—the Tsavo Man-Eaters (aka “The Ghost and The Darkness”). The duo worked together to outmaneuver their prey. During a series of nightly skirmishes, the lions negotiated their way around the camp’s man-made traps and fortifications. They would then target the slumbering workmen, one by one, spiriting them away into the undergrowth. These attacks went on for months, prompting hundreds of workers to flee. News of demon tigers had spread like wildfire through the camps. The bridge project’s overseer, Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson, spent weeks hunting the animals. But they were too clever to fall victim to Patterson’s many and varied traps. Eventually, after several direct encounters, Patterson shot and killed the Man-Eaters. Incredibly, one of the lions took nine bullets before succumbing to its injuries.

2 Leyak

On the Indonesian island of Bali, the Witch Widow, Rangda, reigns supreme. She uses a formidable cult of child-eating witches to terrorize the island’s superstitious population. Together, they are known as the leyak. During the day, the leyak blend in with the crowds. It is only after sunset that the leyak reveals its true form. They spend their nights desecrating grave sites, looking for body parts to steal. These organs are used to craft a magical concoction that grants the leyak its shape-shifting power. Leyak can transform into monkeys, goats, lions, or other animals. If that was not bizarre enough, a leyak can deliberately rip off its own head. It then flies around, entrails dangling in the wind, in search of sustenance.[9] While the creature will happily feast on almost any animal, it favors the blood of mothers and their newborn babies. According to Balinese legend, Rangda’s witch army once waged a war against the king of good spirits, a lion-like beast called Barong. Rangda cast a spell on Barong’s warriors, forcing them to fall on their own swords. But the great guardian prevented this massacre by turning his people invincible. Barong used his mighty powers to overcome the Witch Widow, restoring balance to the Hindu island. The events of this battle are proudly depicted in Balinese ceremonial dances.

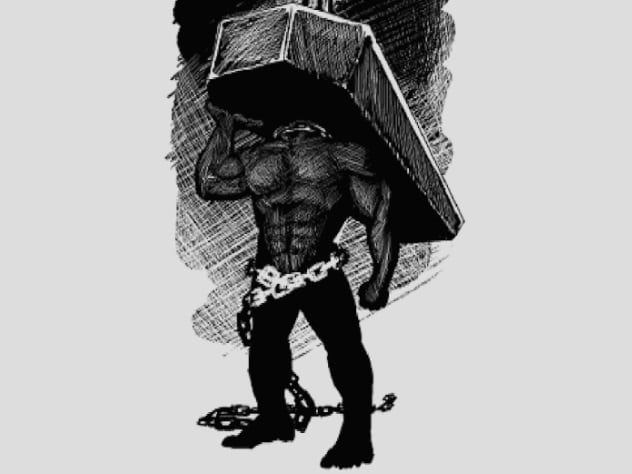

1 Lagahoo

Many communities throughout the Caribbean still believe in black magic (obeah ). It is not uncommon to see citizens sporting protective amulets, which are designed to ward off malevolent entities called “jumbies.” Trinidad and Tobago is no exception. The people of the West Indies nation fear a shape-shifting jumbie named Lagahoo (also spelled “La Gahoo”).[10] Derived from French folklore, the Lagahoo is a muscular man with a coffin for a head. His torso is sheathed in heavy chains, which rattle as he hunts for food. Lagahoo feasts on the blood of livestock and, more rarely, humans. While the Lagahoo spends much of its time looking like a weight-lifting pallbearer, the beast can transform into a variety of animals, including a centaur-like creature. Defeating the Lagahoo is no small task. He must be captured and, for nine long days, beaten with a holy stick. During this rather unforgiving process, the creature will shape-shift into a variety of animals, eventually disappearing in a puff of smoke. The Lagahoo’s French counterpart, the werewolf Loup Garou, is not quite as unshakable. Simply throwing grains of rice into the air is enough to stop this dopey brute in his tracks. Since Loup Garou appears to suffer from obsessive compulsive disorder, the creature must then spend the rest of the night counting each grain of rice.