Last year, 144 US police officers were killed in the line of duty. More than a few of these deaths were the result of ambushes or shoot-outs with perps.[1] In countries like Brazil, where the overall murder total in 2018 was a staggering 63,880 (or 175 deaths per day), Mexico, or Guatemala, police fatalities following shoot-outs are even higher. The point is simple: Being a cop is not an easy job. The following ten shoot-outs are not necessarily the deadliest or most well-known. Don’t expect to see the 1997 North Hollywood gun battle or the 2016 murder of five Dallas police officers by African American militant Micah X. Johnson. This list is focused on the lesser-known, but no less deadly, shoot-outs that pitted police officers against armed thugs, political radicals, and, in one instance, a bunch of angry coal miners.

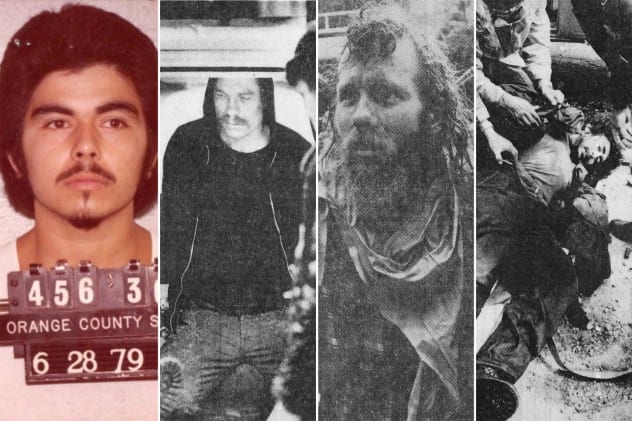

10 Norco Shoot-Out

Norco,is a small, inland desert town in Southern California. It is not the type of place where crime happens often. However, on May 9, 1980, one bank in Norco became a virtual war zone. Just as the Security Pacific Bank was about to close, four masked men left their green van and barged in. A fifth man acted as the getaway driver and lookout. The robbers, aged between 17 and 30, were all armed with semiautomatic rifles or pump-action shotguns. Altogether, the men had over 1,000 rounds of ammunition and were also armed with homemade bombs, grenades, and Molotov cocktails. The first officer to respond to the robbery was Glyn Bolasky, a young deputy with the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department. Deputy Bolasky arrived just in time to see the masked men try to flee the scene with their stolen loot, which amounted to $20,000. The robbers began peppering the window of Deputy Bolasky’s patrol car with rifle rounds. Bolasky was hit in the left shoulder, and the 24-year-old lawman received shrapnel fragments in his face and right arm. All told, the gang fired 200 rounds at Bolasky, and his patrol car was hit with 50 projectiles. Despite this, Bolasky managed to kill the getaway driver, 17-year-old Belisario Delgado, by shooting him with his shotgun. Once Bolasky exhausted his pump-action weapon, he transitioned to his service revolver. Deputy Chuck Hille was next on the scene, and he tried to cover the badly wounded Bolasky. As for the crooks, they stole a truck at Hammer Avenue and took police on a 37-kilometer (23 mi) running gun battle. This chase would destroy or damage 33 police vehicles, force a police helicopter to land, and leave eight officers wounded. In Lytle Creek, California, the gang ambushed Deputy Jim Evans and killed him with a bullet to the eye. Two days later, police arrested George Wayne Smith (right above), Christopher Harven (center left above), and his brother Russell Harven (center right above). The fourth member of the gang, Manuel Delgado (left above), had died during a gun battle with a SWAT team. The three arrested robbers were eventually convicted of 46 felonies, and each was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.[2]

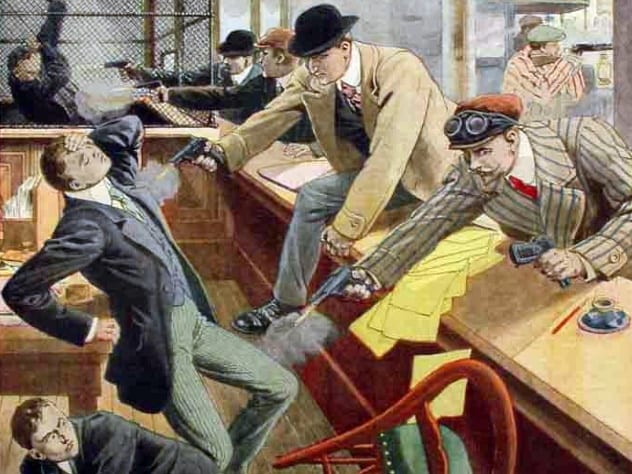

9 ‘Red-Nest’ Shoot-Outs

In 1911, a gang of “illegalist” anarchists coalesced around Octave Garnier. Garnier and his fellow radicals believed that crime could be an act of resistance against capitalism and France’s bourgeoisie. Once the gang made contact with a chauffeur named Jules Bonnot, the group, later christened as the Bonnot Gang, became criminal innovators. Specifically, the Bonnot Gang was the first well-known gang to use automobiles during their heists, starting with a Paris bank robbery (depicted above) in December 1911. The Bonnot Gang also enjoyed technological superiority in the fact that they battled the French police with semiautomatic Browning pistols and shotguns, whereas their opponents were either unarmed or had revolvers. In 1912, the Bonnot Gang were antiheroes to thousands of working-class Parisians. In that year, Bonnot was actually interviewed by Le Petit Parisien. 1912 would prove to be the apogee of the gang, for by April, they were cornered by the French police near the suburb of Choisy-le-Roi. Here, Bonnot and his gang held up in a house armed with three Browning pistols and one Bayard semiautomatic. Arrayed against them were 500 police officers, members of the French army with a brand new Hotchkiss machine gun, firemen, and a local lynch mob. This coalition fired hundreds of rounds at the gangster hideout, while army sappers brought up a case of dynamite in order to blow the building sky-high. Unbeknownst to the men outside, a mortally wounded Bonnot had already written his last words after receiving several wounds.[3] Once the smoke cleared from the shoot-out, a crowd of spectators tried to enter the gang’s hideout in order to gain plunder and desecrate the corpses of the bank robbers. The police and soldiers held them back. At a little past 1:00 AM the next morning, Bonnot and his accomplice Jean Dubois were pronounced dead. A few weeks later, on May 14, Garnier and gangster Rene Valet were surrounded by 300 French police officers and 800 soldiers at Nogent-sur-Marne. The two criminals decided to make a last stand. Their gun battle with the police and soldiers lasted until 2:00 AM the next morning, when the gendarmes used dynamite to blow up the apartment. Garnier died in the explosion, but Valet survived and attempted to continue fighting until he was killed.

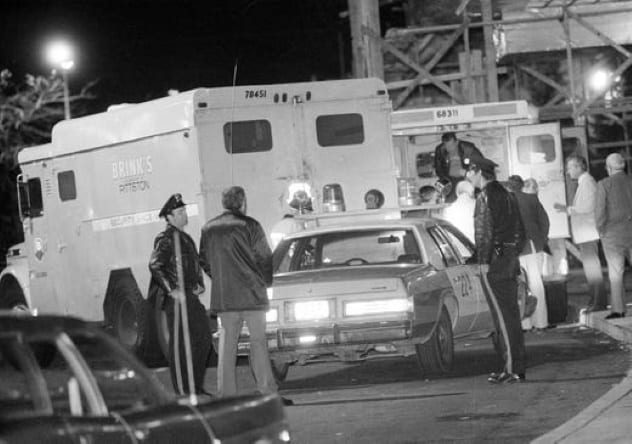

8 Brinks Robbery Shoot-Out

Between the late 1960s and early 1980s, the United States experienced an unprecedented wave of terrorism. Almost all of this terrorism came courtesy of left-wing organizations like the Weather Underground, the Black Liberation Army, and the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Between 1971 and 1972 alone, the FBI recorded 2,500 bombings on American soil. This violence would calm down a little as the 1970s became the 1980s, but the groups responsible for these bombings remained active. On October 20, 1981, members of the Weather Underground, as well as members of the Black Liberation Army and the May 19th Communist Organization, ambushed an armored truck at the Nanuet Mall in Nanuet, New York. The group sought to steal $1.8 million in order to fund their terrorist activities. The gang of robbers leaped out of their rented U-Haul as soon as Brinks security guards Peter Paige and Joseph Trombino began loading bags of cash into their vehicle. The radicals began firing with a shotgun and M-16 rifles. Paige was killed instantly, while Trombino was hit several times. Tragically, Trombino survived the 1981 shoot-out only to die at the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. During their escape, the robbers encountered a police roadblock in nearby Nyack. Nyack police officers Sergeant Edward O’Grady and Officer Waverly “Chipper” Brown were unprepared for six well-armed revolutionaries. Both men were shot to death.[4] Here, the gang split up, with the May 19th and Weather Underground group remaining in the U-Haul and the BLA members leaving the scene in a yellow Honda. U-Haul driver Judith Clark crashed the truck at Broadway in Nyack. Clark pretended to surrender to the police. She was actually reaching for her handgun, but she was apprehended before she could fire any rounds. Clark would be convicted for her involvement in the killing of the two police officers and the Brinks security guard. New York governor Andrew Cuomo commuted Butler’s 75-years-to-life sentence to 35 years in December 2016. A parole board released Butler from prison in May 2019. A month after the shoot-out, following the arrests of most of the gang, Katherine Boudin, David J. Gilbert, and Samuel Brown were indicted for murder. All three had been arrested back on October 20 following a second shoot-out with police. The other members of the group, including ringleader Jeral Wayne Williams (Mutulu Shakur), were arrested in 1985 and 1986. Williams went up for parole in May 2018, but his parole was denied. An investigation of one of the group’s apartments revealed that they had planned to do more than just steal money and “redistribute” it. Police investigators found homemade bombs and plans outlining attacks on New York City Police Department precincts.

7 Newhall Incident

Policing in California changed forever in April 1970. In total, the shoot-out only lasted four and a half minutes, but it would leave four California Highway Patrol (CHP) officers dead. On April 5, 1970, just before midnight, a pair of career criminals named Bobby Augusta Davis and Jack Twinning were pulled over by CHP patrolmen Roger Gore and Walt Frago. The origin of this stop occurred earlier in the day, when Davis and Twinning tried to steal explosives from a construction site near the town of Castaic. When the two men were chased away by suspicious onlookers, they drove off in a hurry. When one of the men flashed a gun, eyewitnesses called the police and told them to be on the lookout for a red Pontiac. When Gore and Frago pulled the car over, they radioed for backup before approaching the suspects. At first, everything seemed normal. Davis, the driver, left the car and put his hands on the hood. As Gore searched Davis, Frago approached Twinning in the passenger seat. Without warning, Twinning leapt up, aimed his Smith & Wesson Model 28 revolver, and shot Frago several times in the chest. Gore shot at Twinning, but he would fall victim to Davis, who used a concealed Smith & Wesson .38 special to shoot Gore at point-blank range. Gore and Frago were both 23 years old. The next officers to respond, 24-year-old George Alleyn and 24-year-old James Pence Jr., immediately came under fire. Pence made his last call, “Newhall, 78-12! 11-99,” before he and his partner were both killed by Davis and Twinning. A passing motorist, Gary Kness, saw the gunfight as it unfolded. Kness, a former Marine, jumped into the fray in order to rescue the wounded Alleyn. Kness could not move the wounded man, but he did pick up one of the CHP shotguns and attempted to fire at Davis. The shotgun proved to be empty. Kness then picked up one of the service revolvers and managed to land a ricochet round that hit Davis in the lungs. After being wounded, Davis decided that he and Twinning should split up. For nine hours, the criminals ran from the police. Twinning eventually took a homeowner hostage before killing himself just as police closed in. Davis was arrested, sentenced to life in prison, and died behind bars in 2009.[5] Following the Newhall incident, the California Highway Patrol rewrote firearms training for all future recruits, issued new procedure instructions for traffic stops, and began testing new weapons in order to give CHP officers an advantage over criminals.

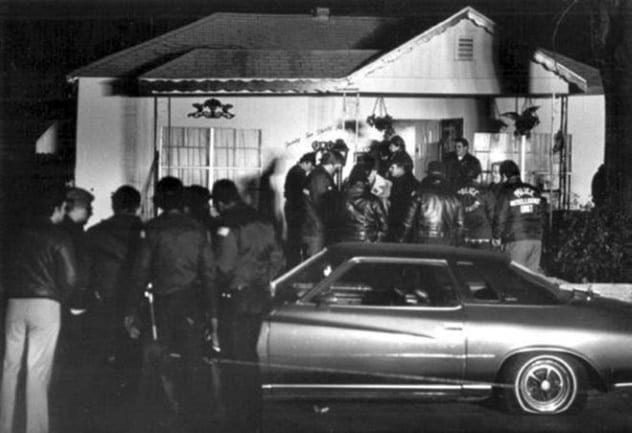

6 SLA vs. LAPD

The Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) is best known as the group behind the kidnapping of American heiress Patty Hearst. However, few know how this radical group met its bloody demise in 1974. The SLA was formed in 1973 by black ex-con Donald DeFreeze, aka Cinque Mtume. DeFreeze convinced a dozen middle-class and college-educated white radicals to join his army in order to defeat America’s “fascists.” During the group’s brief reign of terror, they managed not only to kidnap Patty Hearst but also to rob a branch of the Hibernia Bank in San Francisco, shoot up Mel’s Sporting Goods store, and murder Oakland school superintendent Marcus Foster. That last crime, which occurred on November 6, 1973, saw SLA members put a bullet in Foster’s brain and attempt to kill Foster’s deputy, Robert Blackburn. The SLA killed Foster based on false ideas about his opinions regarding school identification cards and the use of police on Oakland’s campuses. Foster was shot eight times with cyanide-tipped bullets. On May 17, 1974, 500 officers from the LAPD, FBI, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, California Highway Patrol, and Los Angeles Fire Department surrounded a house located at 1466 East 54th Street in Compton. Besides revolvers, the police were armed with AR-15 and AR-180 rifles. The SLA revolutionaries had M-1 carbines that had been converted to automatic fire. These two well-armed sides engaged in a heavy firefight that saw law enforcement officials fire 1,200 rounds of ammo. The police also assaulted the SLA compound with tear gas, but the six militants refused to surrender, despite being engulfed in a fire that had been started by the tear gas. All six SLA members inside, including ringleader DeFreeze, committed suicide rather than be arrested. As for Patty Hearst, she would not be found again until 1975.[6]

5 Siege Of Sidney Street

London’s East End is infamous thanks to serial killer Jack the Ripper and the infamous gangsters the Krays. Less known is the heavy gun battle that pitted left-wing anarchists from the Russian Empire against the British police and army. What later became known as the Siege of Sidney Street first began with a series of murders in Houndsditch. On December 16, 1910, three Metropolitan police officers, 36-year-old Sergeant Robert Bentley, 46-year-old Sergeant Charles Tucker, and 34-year-old Police Constable Walter Choat, were shot dead by a gang trying to rob a jewelry store. The gang, which included already experienced thieves, called itself “Leesma.” Leesma was a mostly Latvian anarchist collective headed by George Gardstein. Other members of the group included the mysterious Peter the Painter and Jacob Peters, the latter of whom would return to Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution and become one of the founders of the infamous Cheka secret police. The next day, at a flophouse room in the East End, the body of Latvian anarchist Poloski Morountzeff was found. He had died after being shot in the back by one of his comrades.[7] The investigation into the Houndsditch murders culminated in the January 1911 Siege of Sidney Street. When uniformed officers arrived at an apartment located at 100 Sidney Street, they were met with gunfire. The police surrounded the area. Seventy-four soldiers of the Royal Scots Guards arrived at the scene. They were accompanied by 35 members of the Royal Horse Artillery and 15 members of the Royal Engineers. These troops were armed with Lee-Enfield rifles, one Maxim machine gun, and several types of explosives, all of which were brought up in order to blow the apartment sky-high. Also at the scene was a young Liberal politician named Winston Churchill. Churchill tried to help by suggesting that an artillery gun be deployed to shell the house ahead of a multi-pronged assault carried out by police constables and soldiers. By 2:30 PM on January 3, the shooting ceased. Firefighters entered 100 Sidney Street in order to put out a raging inferno. Inside were the bodies of two of revolutionaries—Frtiz Svaars and William or Joseph Sokoloff. The rest of the gang were put on trial, but most were acquitted of the triple homicide in Houndsditch.

4 FBI Shoot-Out In Miami

Miami during the 1980s was definitely not a safe place to be. Drugs made the sunny city slick with gore. Miami drank more blood on April 11, 1986, when eight FBI agents found themselves embroiled in an intense shoot-out with two well-armed ex-cons. Michael Platt and William Matix first met at Fort Campbell in Kentucky while both served in the Army. Matix had previously served as a cook in the Marine Corps, while Platt served in Vietnam in 1972 as a member of the elite Rangers. Besides their military backgrounds, both men shared something else in common: Their wives had died under mysterious circumstances. Matix’s wife died during a laboratory robbery in Ohio in December 1983, while Platt’s reportedly committed suicide in 1984. For whatever reason, these two men decided to go on a massive crime spree in October 1985. Their first crime was the murder of 25-year-old Emelio Briel on October 5, 1985. After shooting Briel, the pair stole his car. For the next six months, Platt and Matix knocked off banks and armored cars. On March 12, 1986, after robbing yet another bank, Platt and Matix severely wounded Jose Callazo before stealing his black Monte Carlo. At 9:30 AM on April 11, FBI special agents Ben Grogan and Jerry Dove spotted the Monte Carlo and began following it. The black car would not pull over, so the federal agents pushed the car into a tree. Another special agent, Richard Manauzzi, used his car to block driver’s side. Trapped, Platt and Matix decided to open fire. Matix shot at the FBI agents with a 12-gauge shotgun, while Platt made deadly use of his Ruger Mini-14, a semiautomatic rifle that fires a .223-caliber round. The FBI agents were armed with 9-millimeter and .38 handguns.[8] Grogan and Dove would die during the shoot-out, and so, too, would Matix and Platt. The fact that Matix and Platt continued to fire at the agents despite being hit several times convinced many that both men had to have been on some kind of drugs. A subsequent toxicology report proved that both men were stone-cold sober during the shoot-out. The lasting impact of the shoot-out was that it convinced the FBI to increase the stopping power of their service weapons. The 9-millimeter semiautomatics and .38 revolvers wielded by the agents in 1986 were replaced by .40-caliber handguns after the shoot-out.

3 The Battle Of Blair Mountain

The fact that hundreds did not die during the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921 is a secular miracle. This battle was nothing less than the largest insurrection on American soil since the Civil War. The Battle of Blair Mountain had its roots in the bitter disputes between West Virginia coal miners and their bosses. In the coalfields of Mingo, Logan, and McDowell counties, miners were not paid with US dollars but rather with company-issued scrip. This scrip could only be used at company-owned stores. In order to use scrip to pay the rent, miners had to live in company-owned houses. While the United Mine Workers (UMW) tried hard to improve conditions for the miners, the mining companies relied on “scab” labor and detective agencies in order to keep the unions out of West Virginia’s mines. Things came to a bloody head on May 19, 1920. In the small town of Matewan, West Virginia, Police Chief Sid Hatfield (a member of the infamous Hatfield family) and Mingo County deputy Tony Webb engaged in a gun battle with private detectives of the Baldwin-Felts agency, who were in Matewan in order to evict striking miners from their homes. Hatfield would later boast that he shot three of the detectives dead, including owner Albert Felts, Lee Felts, and C.B. Cunnigham. Another private detective, J.W. Ferguson, was murdered in cold blood as he sought refuge at the home of Mrs. Mary Duty. Hatfield and others were put on trial in nearby McDowell County in 1921. On August 1, 1921, on the steps of the county courthouse in Welch, seven members of the Baldwin-Felts agency ambushed Hatfield and Ed Chambers. Both men were shot several times. The private detectives were never brought to trial. They claimed to have acted in “self-defense.” The killing of Hatfield inspired throngs of miners to strike. Thousands of miners sporting red handkerchiefs met UMW organizers Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney near the state capital of Charleston and began their long march into Mingo County. They intended to free all pro-union miners languishing in the county’s prisons. Once the miners crossed into Logan County, Sheriff Don Chafin, who was anti-union, deployed 3,000 policemen, deputies, and deputized citizens against the miners. On top of Blair Mountain, Chafin’s army erected a series of trenches and machine gun nests. The shooting began on August 31. Over one million rounds would be fired on Blair Mountain, and the battle would continue until September 4. By that point, a squadron of Army Air Service biplanes had been deployed, while President Warren Harding had sent 2,100 US troops into the area in order to end the hostilities.[9] Approximately 1,000 miners laid down their arms. When it was all over, anywhere between 20 and 100 people lay dead. The true extent of the casualties will never be known.

2 Shannon Street Massacre

One of the deadliest days in the history of the Memphis Police Department began on January 12, 1983. A report of a purse-snatching led police to the home of Lindberg Sanders, the self-proclaimed “Black Jesus” who lived with his followers at 2239 Shannon Street. Patrolman R.S. Hester, 34, and his partner Ray Schwill arrived at the house and were immediately greeted with gunfire. Schwill took a round to the face but survived. Hester was taken hostage. Memphis police officers surrounded the house and tried to negotiate with Sanders. Sanders, 49, wanted to broadcast over the radio his warning to the police: Any officer who tried to enter his home would be responsible for Hester’s death. This tense standoff lasted 30 hours. During that time, police officers had to listen in horror as Hester begged for help. When the police finally decided to enter the house, they engaged in a 20-minute gun battle with Sanders and his followers. The police used M-16 carbines and 12-gauge shotguns to kill Sanders and six of his adherents.[10] Sadly, the SWAT team found that Hester had been dead for hours. His captors had stabbed and beat him mercilessly until he died.

1 The Howard Johnson’s Sniper

For 11 hours, Mark Essex, a Kansas native and a former US Navy sailor, held off officers of the New Orleans Police Department. This was simply the climax of the young man’s racist crime spree. By all accounts, Essex grew up a happy child in Emporia, Kansas. He was a Boy Scout, a choir boy, and an expert shot. The fact that he belonged to one of the few black families in the town never seemed to be an issue. In 1969, Essex enlisted in the Navy after spending a lackluster semester in college. According to Essex himself, it was while in the Navy that he was forced to suffer through racist insults and discrimination. Essex wrote letters back home complaining of his treatment, while his superiors began to see Essex as a troublemaker. Before going AWOL on October 19, 1970, Essex had become close friends with another black sailor, Rodney Frank. Frank was a convicted rapist and armed robber originally from New Orleans. It was Frank who turned Essex on to the Black Panthers and the Black Muslims. After a brief return to Emporia, where Essex shocked his former minister by calling Christianity a “white man’s religion,” Essex defended himself at his court-martial by blaming the systemic racism of the Navy for his behavior. The Navy decided to let Essex go in 1971. After spending time in New York City, where Essex studied the urban guerrilla tactics of the Black Panthers and purchased a .44 Magnum carbine, he moved to New Orleans and linked up again with Rodney Frank. It was here that Essex decided to carry one a one-man war on whites and police officers after seeing a news report about a bloody protest at Southern University. In a letter mailed to a local New Orleans TV station, Essex wrote: Africa greets you. On Dec. 31, 1972, aprx. 11 pm, the downtown New Orleans Police Department will be attacked. Reason—many, but the death of two innocent brothers will be avenged. And many others. P.S. Tell pig Giarrusso the felony action squad ain’t sh–t. MATA [11] On New Year’s Eve 1972, Essex shot and killed 19-year-old Cadet Alfred Harrell (who was black) before traveling to Gert Town, a mostly black section of New Orleans. Officer Edwin Hosli Sr. was killed by Essex after he and Officer Harold Blappert responded to the report of a breaking and entering at a warehouse in Gert Town. Days later, on January 7, 1973, Essex broke into the Howard Johnson’s hotel. In room 1829, Essex shot to death Dr. Robert Steagall and his wife Betty. Essex then started a fire in the room. Essex would kill the hotel’s assistant manager, Frank Schneider, and the hotel’s manager, W. Sherwood Collins, before setting more fires. As the hotel was surrounded by police, and as a Marine Corps CH-46 helicopter patrolled the skies above him, Essex went into siege mode. He maintained such a steady and accurate rate of fire that the police thought that they were dealing with two snipers. The 17-hour standoff at the Howard Johnson’s claimed the life of NOPD deputy superintendent Louis Sirgo. Essex, who died after being riddled with bullets, inspired the Beltway Sniper, John Allen Muhammad, who terrorized Washington, DC, and the surrounding area during the early 2000s. Read More: Twitter Facebook The Trebuchet