Millions of people were arrested and terrorized by the Red Guards, the Cultural Revolution’s paramilitary youth organization. Those arrested were forced to endure brutal “struggle sessions,” where they were tortured and humiliated in public. By the time the revolution ended in 1976, possibly as many as three million people had been killed. The violence and persecution during the revolution was catastrophic, and the decade arguably ranks as one of China’s darkest periods.

10 The Execution Of Fang Zhongmou

Fang Zhongmou, a Communist Party member and veteran of the People’s Liberation Army, felt proud when her two older children got caught up in the furor of the Cultural Revolution and became Red Guards. Fang’s enthusiasm, however, began to wane after her daughter got sick and died following a trip she made to see a Mao Tse-tung rally in Beijing. Her husband was then accused a few months later of being a capitalist roader, a vague Maoist slur which referred to somebody who was working to betray the ideals of the Communist Party and lead China to a capitalist system. Due to a past accusation of her father being a Nationalist spy, it wasn’t long before Fang was suspected of being a dissident as well. Like her “capitalist-roader” husband, she was put in detention multiple times and subjected to struggle sessions by the authorities. While home one day in 1970, Fang angered her husband and her son Zhang Hongbing after criticizing Mao Tse-tung. Fang’s family duly reported her to the authorities, and she set the family portrait of Mao on fire in retaliation. She was then taken away by a soldier but not before Hongbing beat her on orders from his father. For the crime of “attacking Chairman Mao Tse-tung,” Fang was executed by firing squad on April 11, 1970. Neither Hongbing nor his father attended the execution. In the years following his mother’s death, Hongbing realized what a terrible thing he and his father had done. With the help of his uncle Feng Meikai, Hongbing was able to influence his province’s legal system to clear his mother’s name in 1980. He has since become a lawyer, active in raising awareness of the Cultural Revolution’s victims and fighting to have his mother’s grave turned into a memorial.

9 The Paralysis Of Deng Pufang

From ordinary peasants to high-ranking party members, nobody in China was truly safe during the Cultural Revolution. Not even Deng Xiaoping, the high-ranking leader best remembered for his post-Mao capitalist reforms in China in the 1980s, was safe from the revolution’s purges. In 1967, while serving as the Communist Party’s general secretary, Deng was denounced as a capitalist roader and removed from his position. He then spent the next two years under house arrest in Beijing, forbidden to leave or see his children. While the worst thing that most of his children suffered was being forced to work in the countryside, Deng’s oldest son, Pufang, became paralyzed after an encounter with the Red Guards. In 1968, a group of Red Guards captured Pufang on the campus of Beijing University and tortured him for the sole reason of being his father’s son. After clubbing him, the Red Guards locked a dazed Pufang in a fourth-story room. Pufang has never been able to remember what happened next. Either his torturers pushed him out an open window or he attempted suicide by jumping out the window himself. Fortunately, Pufang survived the fall. But he did break his back and become paralyzed. Since the Dengs were political pariahs, Pufang was denied the treatment he needed. By the time some specialists finally examined him in 1974, Pufang was already permanently paralyzed. While still bound to a wheelchair today, Pufang has worked tirelessly the past few decades for the rights of the handicapped in China. In 2003, he was awarded the United Nations Prize in the Field of Human Rights for his humanitarian efforts.

8 The Murder Of Bian Zhongyun

One of the earliest victims of the Cultural Revolution was Bian Zhongyun, a 50-year-old vice principal at the prestigious Beijing Normal University Girls High School. In June 1966, some of the school’s students began to criticize school officials and organize revolutionary meetings. Bian’s college degree and bourgeois background made her a natural target for the revolutionaries, although many of them were ironically from privileged families themselves. Over the next two months, Bian was repeatedly harassed by her students and even beaten during a meeting. On August 4 of that summer, Bian was tortured and warned not to come to school the next day. But she decided to come in that morning anyway. It was a courageous decision that would cost Bian her life. First, her teenage students beat and kicked her. Then they whacked her with nailed-filled table legs. The attack was so terrible that Bian soiled herself and was knocked unconscious before dying of her wounds. Nobody was ever punished for her murder, and even today, the perpetrators have yet to step forward. In January 2014, Song Binbin, a famous Red Guard and one of Bian’s students at the time she was killed, made a public apology for her death. Although Song claimed that she had no direct part in Bian’s beating, she felt guilty for not being able to stop it. Some critics, however, felt the apology was insincere and that Song had a larger role than she was willing to admit. Bian’s husband, Wang Jingyao, was also not impressed with the apology. In one interview, he said that Song was a “bad person,” although he believed that the Communist Party and Mao Tse-tung were also responsible.

7 The Down To The Countryside Movement

The Down to the Countryside Movement was a massive relocation program that ultimately sent over 17 million young urban Chinese into rural areas across the country between 1968 and 1980. While some of these “sent-down youth” left the cities voluntarily, the vast majority were coerced against their will. Due to a variety of factors, including urban unemployment and the Cultural Revolution’s disruption of the education system, Mao Tse-tung proclaimed in 1968 that it was “very necessary for the educated youth to go to the countryside and undergo reeducation by the poor peasants.” Ideally, the relocation program would cultivate the sent-down youth’s commitment to party ideology and foster economic growth in underdeveloped areas. The young urbanites, fresh from high school, university, and even elementary school, were forced to endure backbreaking labor jobs and the extreme poverty common in the countryside at the time. Although some of the youth saw the policy as a great opportunity for adventure or patriotism, others resented the harsh work and poor living conditions and yearned to return home. Most of the sent-down youth did eventually return home, but the many years they spent in the countryside remained lost. They’ve become known as a lost generation, an immense group of people who were denied the chance to finish school and maximize their potential. As one Beijing history professor put it, “From the perspective of a historian, from the perspective of the entire nation’s development, this period must of course be negated.”

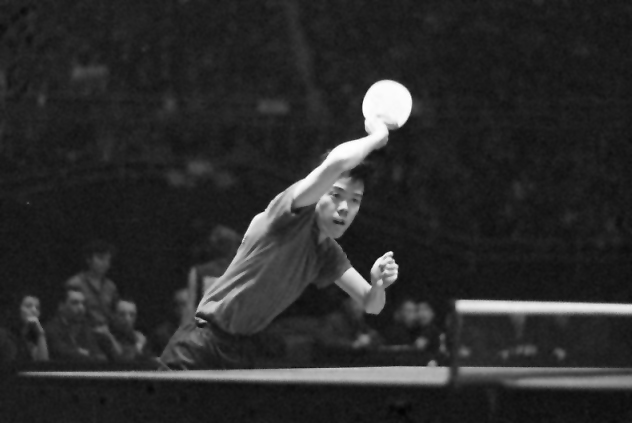

6 The Ping-Pong Spies

Rong Guotuan, Fu Qifang, and Jiang Yongning were three of the biggest names in Chinese ping-pong during the 1950s and 1960s. Rong was especially popular, and he was considered a national hero for being the first Chinese to win the World Table Tennis Championships in 1959. Despite playing for the Chinese, all three men had originally come from Hong Kong, which at that time was controlled by the British. As foreigners, the three ping-pong greats were deemed untrustworthy by their countrymen during the Cultural Revolution, and they were all accused of being spies in 1968. Fu was subjected to struggle sessions and beatings by his own teammates, and he eventually committed suicide on April 16 of that year. Jiang would hang himself a month later. His hobby of reading newspapers, along with a childhood picture he had of himself wearing a Japanese flag during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, was enough to convince the authorities that Jiang was a Japanese spy. Given the humiliating accusations against him, Rong decided to follow in Fu’s and Jiang’s footsteps. Early in the morning of June 20, Rong wrapped a rope around the branch of an elm tree and hanged himself. In his pants pocket, Rong left a note that pleaded for his innocence. “I am not a spy,” he wrote, “Please do not suspect me. I have let you down. I treasure my reputation more than my own life.” The National Sports Commission remained unconvinced, however, insisting that the three men were operating a Hong Kong spy network.

5 The Death Of Lao She

Lao She, the pen name of the Manchu writer Shu Qingchun, is widely regarded as one of the greatest authors of modern Chinese literature. His 1937 novel Rickshaw Boy, the tragic story of a poor rickshaw puller in Beijing, is so popular that there’s a statue of the main character on the city’s Wangfujing Street. Such was the admiration for the “people’s artist,” as Lao She was nicknamed, that Chou En-lai, China’s first premier, asked him in 1949 to come back to China after he had moved to New York three years earlier. On August 23, 1966, as the Cultural Revolution began to gain steam, Lao She and 20 other writers were transported to Beijing’s Temple of Confucius, where a mob of 150 teenage girls beat them with bamboo sticks and theater props in a brutal struggle session. Later that night, after the writers were taken to the city’s Culture Bureau offices, Lao She was beaten for hours without end after he refused to wear a placard that said he was a counterrevolutionary. Finally, around midnight, the mob stopped and Lao She was allowed to go home. The next day, after earlier leaving his house in the morning, Lao She’s body was found drowned in a lake. It’s believed that the humiliation Lao She suffered during his struggle session drove him to kill himself, although his wife Hu Jieqing suspected that he was murdered. The exact circumstances surrounding Lao She’s struggle session are shrouded in mystery. It’s uncertain who organized the session and whether Lao She attended voluntarily or against his will. If Lao She did go freely, he might not have known what the unidentified organizers—possibly a trio of younger writers who disliked him—were plotting.

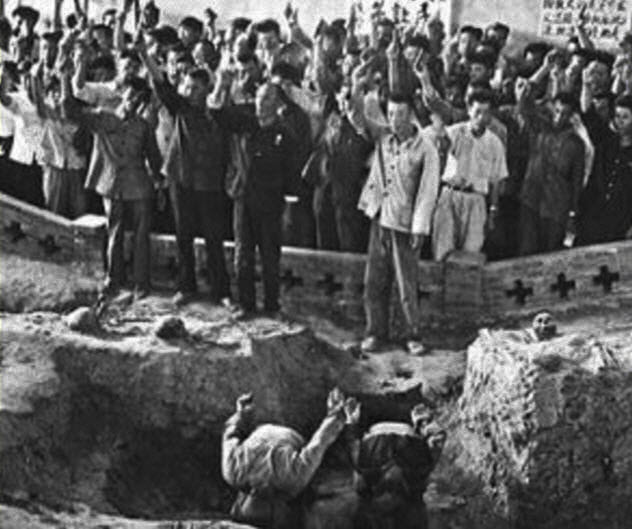

4 The Dao County Massacre

In summer 1967, a rumor began to spread around Hunan Province’s Dao County that there was going to be an invasion of mainland China by Taiwan. The Kuomintang, Taiwan’s ruling party and the former rulers of China from 1928 until 1949, was allegedly going to cooperate with antirevolutionaries to take back the mainland. The antirevolutionaries were also planning to conduct a massive purge in the county, wiping out all the members of the Communist Party and the peasant leaders in the local government. The invasion was a completely groundless rumor, but the county government’s confirmation that it was true set off a massacre that claimed the lives of over 4,500 people in only two months. Many of the victims were members of the Five Black Categories, a group that the Communists identified as landlords, rich farmers, counterrevolutionaries, bad influencers, and rightists. Some of the victims were killed by armed militias in their own homes, while others were given a mock trial and then killed by mobs. Victims were variously shot, decapitated, buried alive, and in some instances, blown up with explosives. The violence got so out of hand that it spread to nearby counties, eventually resulting in another 4,000 deaths. When all was said and done, over 14,000 people were thought to have participated in the massacre in Dao County. By the 1980s, 52 of the participants had been arrested and given prison sentences, but the vast majority were never punished.

3 The Cleansing The Class Ranks Campaign

To “cleanse the class ranks” of counterrevolutionaries and capitalists, the Communist Party operated revolutionary committees nationwide to root out its perceived enemies. From 1968 until 1971, the committees launched a campaign of terror across the country. One area especially hit hard was Inner Mongolia, where an alleged secret Mongolian separatist party was said to be carrying out counterrevolutionary activities. Hundreds of thousands of people, mostly Mongolians, were arrested, maimed, or tortured. Another 22,900 people were killed. Other provinces, such as Hebei and Zhejiang, also experienced huge purges. As part of a crackdown on an alleged Kuomintang spy ring, 84,000 people were arrested in Hebei. Over 2,900 suspects are recorded as having died from injuries they received from being tortured. In Yunnan, as estimated by the province’s Cleansing the Class Ranks Office, almost 7,000 people suffered “death from enforced suicide.” The Cleansing the Class Ranks Campaign began to fizzle after only a year in 1969, although it lasted in some areas until 1971. The large-scale arrests and executions eventually unnerved Mao Tse-tung, who feared that the purges had gone too far and could hurt his public image.

2 Project 571

During the 1960s, the great general Lin Biao was one of Mao Tse-tung’s most trusted men. He was vice chairman of the Communist Party and Mao’s designated successor. While Lin survived the early purges of the Cultural Revolution unscathed, Mao became increasingly worried about his influence in the party. By 1971, Lin and his supporters had fallen out of favor with the Maoists, and Lin found himself isolated from the party leadership. On September 13, 1971, Lin, his wife, and his son Liguo boarded a plane and tried to flee to the Soviet Union. The plane’s fuel was low, and the Lins were in such a hurry that they didn’t bother to bring a copilot or navigator with them. As government officials followed the plane on radar, it passed over Mongolia and then crashed. There were no survivors, and while the nine corpses that were aboard were scorched, autopsies conducted by the Soviet Union were later able to identify the remains of the Lins. In the days before the crash, the Chinese government had uncovered a conspiracy by Lin Biao to launch a coup. The plot, code-named Project 571, also intended to assassinate Mao Tse-tung. According to the party’s account, the Lins attempted to escape China after the coup failed. Their plane crashed, however, after running into technical difficulties. Despite what the Communist Party maintains, there is still a great deal of controversy over Project 571. Critics believe that it was Lin Liguo, not his father, who was probably the head of the conspiracy. In fact, Lin Biao might have been entirely innocent. The cause of the plane crash has also been disputed. Some skeptics have suggested that the plane was sabotaged or shot down. Strangely, the plane’s pilot Pan Jingyin was posthumously given the honorary title of “Revolutionary Martyr.”

1 Cannibalism In Guangxi Province

According to the research of Zheng Yi, a Chinese dissident and writer, hundreds or possibly thousands of people were cannibalized in the province of Guangxi during the Cultural Revolution. During his time as a Red Guard in Guangxi, Zheng heard stories about the cannibalism, but he never witnessed any incidents himself. In the mid-1980s, Zheng returned to Guangxi to see if the stories had any truth to them. Shockingly, he found and interviewed many participants, and few of them spoke with any remorse or fear of reprisal. Zheng found that the participants ate their victims not out of starvation but as a commitment to political ideology. Simply killing the revolution’s enemies wasn’t enough. They believed it was necessary to eat and completely destroy them. Participants ate brains, feet, livers, hearts, and even genitals. They held human flesh barbecues and banquets with their friends and families. In Wuxuan County, where the cannibalism was most prevalent, victims would be stalked by crowds and then pounced upon. Some of the victims were cut and skinned while they were still alive. In one incident in 1968, a man was beaten on the head, castrated, and then skinned and cut open alive by a mob. Children and elderly people also took part in the cannibalism. One old woman was infamous for cutting out and eating victims’ eyeballs. In another incident, a female teacher was killed by her students and barbecued at their school. The incidents of cannibalism in Guangxi remained unknown outside of China until Zheng left the country and publicized the episode in his book Scarlet Memorial in 1993. The Chinese government has banned Zheng’s book, and even today, officials are reluctant to talk about what happened in Guangxi.