The grandson of American industrialist J. Paul Getty, JPG III grew up in Rome, where his father was in charge of part of Getty Oil’s European operations. JPG III grew up in the 1960s as a rebellious young man, managing to get himself kicked out of the exclusive private school he’d attended. On 10 July 1973, JPG III was kidnapped. His captors sent a note to his parents demanding a $17 million ransom. The family did not initially reply; some of his relatives scoffed at the demand, believing JPG III had staged his own kidnapping for financial reasons, something he had joked about on occasion. His kidnappers sent another demand, but Italian postal workers went on strike, delaying its arrival. After several weeks, the family asked the patriarch, J. Paul, for the ransom. He refused, saying that it might encourage the kidnapping of his other grandchildren. Finally, in November, the kidnappers sent a lock of JPG III’s hair and his severed ear, a much smaller ransom demand (now just over $3 million), and a note threatening to send the rest of JPG III back to the family piece by piece. J. Paul finally agreed to fund the ransom, but only the amount that was tax deductible (just over $2 million); he would loan the remainder to J. Paul Jr, who would in turn have to repay the rest, at interest. JPG III was released by his captors, and found the week before Christmas. Of the dozen-plus who were involved in the kidnapping, only two were ever convicted. Several years later, JPG III had surgery to reconstruct the severed ear. He was disabled in the early 1980s by a drug overdose, and remained in poor health until his death in early 2011.

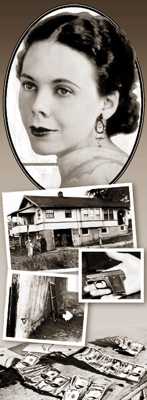

Henry McElroy was the City Manager of Kansas City, Missouri, in the early 1930s. One late spring evening in 1933, his twenty-five-year-old daughter Mary was bathing in her father’s home, when a gang of four masked men used a shotgun to force their way into the house. Mary and her kidnappers reportedly had a rather jovial conversation: when the kidnappers demanded that she accompany them, she asked for time to finish her bath and get dressed. When they told her that they were going to demand $60 thousand, she replied, “I’m worth a lot more than that.” Mary’s captors held her in the basement of a farmhouse in Shawnee, in nearby rural Kansas. Her father paid a negotiated ransom of $30 thousand, and she was released after a day and a night in captivity. Three of her four kidnappers were arrested over the next month. Mary suffered crippling shame and embarrassment after the kidnapping. At her captors’ trial, she refused to cooperate with prosecutors. She publicly expressed sympathy for her kidnappers, even pleading (successfully) for clemency when the ringleader was sentenced to death. Her life after the kidnapping was very difficult; she suffered one nervous breakdown before the trial, and several after. She eventually took her own life in 1940, leaving a suicide note in which she stated that her captors were the only people on earth who didn’t think she was a fool.

Twenty years after Mary McElroy’s captivity, Kansas City was the scene of another infamous kidnapping. Bobby Greenlease was the six-year-old son of Robert Greenlease, a wealthy businessman who owned General Motors dealerships in several states. Bobby was kidnapped from his school by Bonnie Heady, a petty criminal and drug addict. Heady pretended to be Bobby’s aunt, and claimed that Bobby’s mother had suffered a heart attack. Bobby accompanied her willingly. After taking Bobby captive, Heady rejoined her boyfriend, Carl Hall. The two drove Bobby across the state line into Kansas, where Hall shot and killed the boy. They then sent a demand to Bobby’s father, naming a ransom of $600,000. Mr Greenlease, desperate to get his son back, followed the kidnappers’ instructions, did not fully cooperate with the police, and agreed to pay the ransom. (At this point, $600,000 was the largest ransom paid in a kidnapping in the United States.) Hall and Heady collected the ransom, then split up and waited for things to “cool off.” Hall left Kansas City for St Louis, where a prostitute that he did business with saw the money. She informed police about the large sums of cash that Hall was carrying; the police questioned Hall, who eventually implicated Heady. When police arrived at her residence in Kansas City, they found Bobby’s body, buried in her backyard. Hall and Heady were convicted, and were both executed in 1953. Only half of the ransom money was ever recovered; an unscrupulous police officer is rumored to have “recovered” some of it for himself.

In the early 1960s, the government of New South Wales was having difficulty funding the construction of the world-famous Sydney Opera House. To increase revenue, they sponsored a series of lottery drawings, with 100,000 pound prizes. (This amount would be the equivalent of about $4.5 million today.) The winners of one of the drawings were Bazil and Freda Thorne. As was the custom, their identities were published, along with their home address, when the prize announcement was made. About a month later, their eight-year-old son Graeme, was waiting at the curb for a family friend to give him a ride to school. He was snatched up by Stephen Bradley (born Ishtavan Baranyay, a Hungarian émigré), who had previously “cased” the Thorne residence, using a ruse to learn their phone number etc. The family friend arrived at the pickup spot, and quickly determined that Graeme was not at school. Less than an hour after the kidnapping occurred, police were at the Thorne residence, gathering information. While the police were still in the residence, a phone call came (answered by one of the officers) demanding a ransom of 25,000 pounds. The kidnapper called the police several additional times; the ransom was never delivered. The police went public with the story almost immediately, begging for help with finding the boy. Sadly, his body was discovered about five weeks after the kidnapping. He had died of a head injury less than 24 hours after being abducted; he may have accidentally received the injury during the kidnapping itself. Three months after the kidnapping, Stephen Bradley was arrested. He was convicted and sentenced to life in prison; the prosecution built a textbook case on forensic evidence (carpet fibers, hair, pollen etc.) Bradley died in prison in 1968.

Lesley Whittle was the seventeen-year-old daughter of George Whittle, a wealthy businessman. Donald “Black Panther” Neilson was a successful burglar who graduated to murder when one of his victims, who happened to be home when Neilson broke into his house, confronted him. Neilson killed the homeowner quickly and violently; the victim’s wife told reporters that her husband’s killer wore black and moved “like a panther” and thus was born the nickname. In the early 1970s, George Whittle was being sued by his wife over financial maneuvers he had undertaken to keep her from receiving any of his money should he die or she sue for divorce. Tales of their dispute made the Daily Express and other newspapers, where Neilson read about them. Neilson thought he could kidnap Whittle’s son, or common-law wife, and demand a 50,000 pound ransom. Whittle was wealthy enough, Neilson figured, to pay that amount quickly and without protest. Neilson broke into Whittle’s home and found Lesley. He captured her and left his demand. Through a series of mishaps, the ransom drop was never made. Neilson had left Lesley, hands tied, tethered by a wire around her neck, in the sewers near Bathpool Park, Staffordshire. While Neilson was waiting for the ransom, and subsequently fleeing when it was not delivered, Lesley fell (or perhaps was pushed by Neilson) down a shaft in the sewers and died. Neilson was captured eleven months later; carrying a sawed-off shotgun, he managed to take two policemen captive. They reversed the situation and arrested him. He was found guilty of the murder of Lesley Whittle, and several others from his robberies. He has been incarcerated since 1975.

In December 1981, Nina von Gallwitz, the eight-year-old daughter of a bank officer from Cologne, Germany, was kidnapped while walking to school. Her parents agreed to the kidnappers’ demands, and attempted to pass the ransom to them. The kidnappers were exceptionally careful and skittish; they bailed out on the Gallwitzes’ first few attempts to ransom their daughter when circumstances weren’t to their liking. Fortunately, after every unsuccessful attempt, the kidnappers made contact again, giving Nina’s parents new instructions, sometimes in recordings of Nina’s own voice. (The kidnappers also raised the amount of the ransom demand, eventually to the sum of 1.5 million Deutschmarks.) Finally, in May 1982, the Gallwitzes successfully passed the ransom to the kidnappers by throwing it from a speeding train. Three days later, Nina, weak but otherwise okay, wandered into a highway rest area. She reported being confined in a small crate or box for extended periods of time, but was otherwise unharmed. She had spent five months in captivity. Due to the care—dare we say “professionalism”?—of the kidnappers, few clues were discovered. The only notable exception was the discovery of several thousand Deutschmarks from the ransom in a forest some twenty-five miles from Cologne. Nina’s captors have never been apprehended.

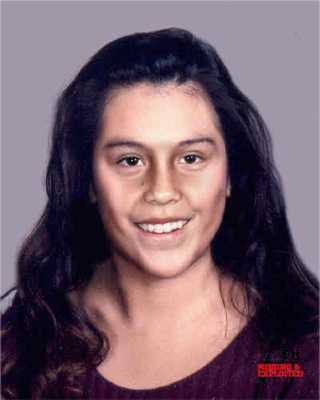

Anthonette Cayedito, a nine-year-old Navajo girl, was snatched from her family’s home in Gallup, New Mexico, in April 1986. According to Anthonette’s sister, a man claiming to be their uncle grabbed Anthonette, pulled her into his car, and drove away. Several people reported sighting Anthonette in the days following the kidnapping. She also may have called 911 in 1987, in an attempt to escape her captors. The most frustrating possible missed opportunity took place in Las Vegas, Nevada. A waitress there reported seeing a young girl traveling with an unkempt man and woman. The girl kept dropping her fork on the floor and grabbing the waitress’s hand when she brought fresh silverware to the table. After the group had left the restaurant, the waitress discovered a note written on a napkin, placed under the girl’s plate: “Help me. Call the police.” When shown a picture of Anthonette, the waitress said that the girl had strongly resembled her. Anthonette has never been found. No one knows the identity of the girl, who might have been Anthonette, nor of the couple she was traveling with.

Carlina White was born on 15 July 1987. She was nineteen days-old when her parents took her to Harlem Hospital Center in New York City for a high fever. She was receiving intravenous antibiotics, when a woman posing as a nurse removed the IV and abducted her. Hospital workers had noticed the woman hanging around the hospital for several weeks, but no one knew who she was. The city of New York offered a $10,000 reward for information leading to Carlina’s return. Her parents sued the hospital, and eventually received a large settlement. Carlina was raised by a woman named Ann Pettway, who told the girl that her name was Nejdra Nance. The pair first lived in suburban Connecticut (less than an hour from Carlina’s former home), then Atlanta, Georgia. During her teen years, several factors made her doubt that Pettway was her mother. Carlina noticed that she did not physically resemble her mother for example, and Pettway’s explanations for her inability to get a social security card, or produce a birth certificate, were unconvincing to Carlina. In 2010, now in her early twenties, Carlina found photos on the Internet of herself as an infant, pre-kidnapping, and saw a strong resemblance between those pictures and the pictures Pettway had of her as a small child. She also saw a strong resemblance between the old pictures of Carlina White and her own baby daughter. She contacted the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, and through them was able to confirm her identity and make contact with her birth family, twenty three years after her abduction. Ann Pettway turned herself in to the Federal Bureau of Investigation in January 2011. She told agents that she had kidnapped Carlina after suffering a series of miscarriages, and despairing of ever being a parent.

Patty Hearst is the granddaughter of William Randolph Hearst. In February 1974, at age nineteen, she was kidnapped from an apartment she shared with her fiancée. Her kidnappers were part of a guerrilla group, the Symbionese Liberation Army. (The name “Symbionese” refers to “symbiosis,” living together in interdependence and harmony.) The SLA initially attempted to trade Hearst for the freedom of jailed SLA members. When this failed, they demanded that the Hearst family donate hundreds of millions of dollars of food to the needy in California. The Hearsts immediately donated $6 million dollars of food to groups that fed the poor in the Bay Area. The SLA refused to release Patty, claiming that the food was of inferior quality. In April 1974, the SLA released a tape on which Patty Hearst said that she had joined the group and shared its rejection of capitalism and western values. She said she was taking the name “Tania,” after the name of Che Guevara’s comrade Tamara Bunke, and made subsequent communiqués under that name. Later that month, she was photographed in security footage shot during an SLA bank robbery; the photograph of the heiress, toting an M-1 carbine while shouting orders at bank customers who had become her captives, is one of the iconic pictures of Vietnam War era America. A shootout in Los Angeles, and subsequent police siege, led to the deaths of many of the members of the SLA. Hearst was arrested in the fall of 1975, along with several of her SLA surviving comrades. She served twenty one months of a seven year sentence. President Jimmy Carter commuted her sentence and in 2001, she received a full pardon from President Bill Clinton.

Four years after his famous trans-Atlantic flight, Charles Lindbergh and his wife, Anne Morrow Lindberg, had their first child, Charles Jr. On the evening of 1 March 1932, the baby’s nurse put him to bed. She heard a noise outside the house later that evening and when she went to check on Charles Jr, he was not in his crib. While looking for the boy, Charles found an envelope on the windowsill. When police opened it, they found a ransom note, filled with misspellings. The kidnapper demanded $50,000, and promised to contact the Lindberghs after two or three days to instruct them on how to ransom their child. Police found some physical evidence—a footprint in the dirt below the nursery window, a home-made ladder that had been left in the bushes—but they failed to secure the scene. The evidence’s value was compromised, as it had been trampled by media and police. Further instructions arrived a few days later, but instead of passing this note on to the police, Lindbergh gave it to an acquaintance who claimed to have mob connections. Due to Lindbergh’s fame, organized crime figures (including Al Capone) offered to help the Lindberghs recover their son. Two more ransom notes arrived in quick succession; the ransom had increased to $100,000, due to the Lindberghs involving the police. All these ransom notes were postmarked from New York City. A retired school teacher from the city, John F Condon, had written several letters about the kidnapping. These letters were published in The Bronx Home News. The kidnappers chose Condon as their intermediary with the Lindberghs. They sent several more notes through Condon, the next-to-last of these was accompanied by the pajamas that Charles Jr had been wearing the night of his abduction. One month after the kidnapping, Condon (followed by Lindbergh) went to deliver the ransom. The package included gold certificates, which (because the government was about to withdraw them from circulation) would be easier to trace than cash. Condon’s contact sent him on a wild chase across Manhattan. The path ended in St Raymond’s Cemetery, where a man accepted the payment and gave Condon a note, indicating that Charles Jr was being held on a boat called “The Nelly,” on Martha’s Vineyard. The mysterious man said that the child was accompanied by two women who did not know his identity. Lindbergh raced to the island, but found that there was no boat there by that name. Six weeks later, a truck driver found Charles Jr’s body in the woods only a few miles from the Lindbergh home. The body was badly decomposed; the apparent cause of death was a severe skull fracture. The discovery of the dead child prompted the United States Congress to make kidnapping a federal crime; this made for the speedy involvement of the FBI in the investigation of kidnappings. Suspicion fell on several potential kidnappers, including servants from the Lindbergh household (one of whom committed suicide) and John F Condon. Two years later, one of the gold certificates from the ransom turned up. It had a number written on it in pencil; agents determined that the number was from a license plate, and traced the certificate to a gas station. The attendant remembered the man who had passed the certificate had behaved suspiciously, so he had written down the man’s license plate number. That man proved to be Bruno Hauptmann, a small-time crook who had emigrated from Germany. Searching Hauptmann’s apartment, police found a drawing of plans for a home-made ladder like the one found at the Lindbergh residence. They found John Condon’s phone number and address written on a wall of the apartment. Police also found a small piece of wood, of the same kind as the ladder, bearing tool markings that matched markings on the home-made ladder. At Hauptmann’s trial, the prosecution presented their strong circumstantial case. Both Lindbergh and Condon testified that Hauptmann was the man who received the ransom in St Raymond’s Cemetery. While he maintained his innocence throughout the trial, Hauptmann was convicted and sentenced to death. He refused a last minute reprieve, because he would have been required to confess to the crime. He was executed in New Jersey’s electric chair on 3 April 1936, four years, one month and two days after the kidnapping.