Among the amazing discoveries, archaeologists have found that the Neanderthals had a surprising fashion sense, that ancient artists risked their lives for their craft, and that at least one ancient musical instrument still works.

10 Neanderthals Wore ‘Body Glitter’

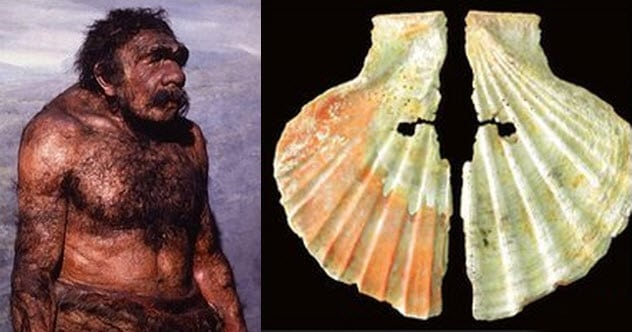

Several discoveries in Spain suggest that Neanderthals were more fashion-forward than previously believed. The first came in 1985 at the Cueva de los Aviones, a cave site in Murcia. There, archaeologists uncovered a bunch of perforated shells which they say were strung up and worn as a necklace. Even better, these 50,000-year-old shells, along with a similarly aged scallop shell discovered more than 20 years later at another site in Murcia, still showed traces of red, orange, and yellow pigments. These pigments were made from minerals like charcoal, pyrite, and hematite. According to researchers, they were then applied to oneself like caveman body glitter.[1]

9 People Of The Atacama Worshiped Llamas

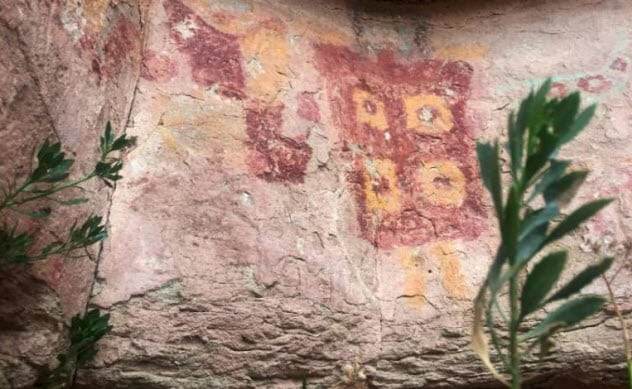

The Atacama’s Alero Taira rock paintings reveal the sacred significance of nature, especially the llama. About 90 percent of the artwork, which is between 2,400 and 2,800 years old, depicts llamas. The Rumualda Galleguillos, extant indigenous inhabitants of the Atacama who still raise llamas, revere natural processes like volcanoes and springs as deities. And the llama, most hallowed of desert fauna, was born of desert springs. These furry holy symbols were often sacrificed to the Mother Earth, Pacha Mama. The Taira rock art itself was created to appease the deities and ensure a fruitful llama harvest. The art also reveals ancient psychology. Human figures are rare. When they do appear, they’re always painted small, probably to represent humanity’s relative insignificance in the grand scheme of nature.[2]

8 Ancient Artists Risked Their Lives

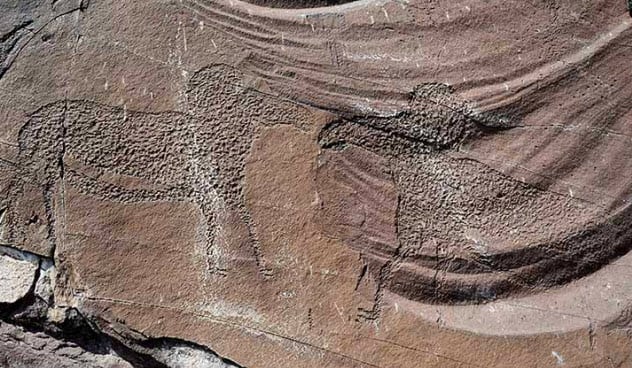

The damming of the Siberian Yenisei River led to the discovery of some insane petroglyphs that would have otherwise remained out of sight due to their dizzying heights. The decorated cliff face is like a Neolithic art gallery. Though some pieces are now more than 30 meters (100 ft) underwater and obscured forever, others are made visible for the first time in millennia. The art depicts animals like elk and aurochs. One especially inaccessible 5,000-year-old glyph portrays a fierce battle between two argali, horned mountain sheep. It’s even more amazing because it shows us the dangers faced (voluntarily) by ancient artists in pursuit of their craft. The location of the image is so ruggedly impossible that researchers say that it could barely be reached even with modern, “state-of-the-art climbing equipment.”[3]

7 Musicians Made Tiny ‘Jaw Harps’

The mouth harp, a reed attached to a frame which you put to your lips and pluck at, is one of the world’s earliest musical devices. Its relative simplicity makes it a historical favorite, exemplified by five 1,700-year-old jaw harps (aka “Jew’s harps”) found in the Siberian Altai Mountains. These are fancier than other regional models because they’re crafted from cow or horse ribs rather than deer antlers. Three of the harps were works in progress, but the other two were finished. Amazingly, one is in working order, still producing the notes it did when the Huns dominated Europe nearly 2,000 years ago.[4]

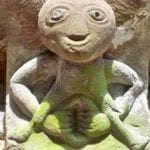

6 Ghanaian Terracotta Figurines Reveal Trade Routes

The Chinese Terracotta Army is world-famous, but the lesser-known Ghanaian terracotta figures are equally packed with history. They were crafted by a mysterious civilization from the Koma Land culture of northern Ghana. A recent biological scan reveals that these unknown people fostered extensive trade routes that crisscrossed Asia and Africa. During arcane rituals, the hollow figures were filled with various substances, like bananas, which were not locally available and might have come from Asia.[5] Researchers also found DNA from grasses and pine trees imported from the opposite side of the continent. Boiled pine bark and needles is a medical concoction, so these rituals may have conferred health benefits.

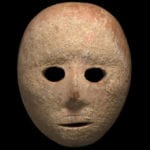

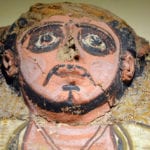

5 Egyptian Art Became Depersonalized

More than a century ago, a Nile explorer stumbled upon a rock with the image of a bowling-pin-headed figure. Scientists think it might be Egypt’s founding pharaoh, Narmer, who united Upper and Lower Egypt more than 5,000 years ago. The image dates back to between 3200 BC and 3100 BC, around the same time that Narmer become Egypt’s first supreme ruler. The 3-meter-wide (10 ft) “tableau 7a” depicts the king and his bowling-pin-shaped white crown along with a royal procession of pennant bearers, fan wavers, trusty hound, and giant ships towed by bearded men.[6] It’s unlike Egyptian art of the next few millennia, in which images of living kings were replaced with a symbolic bull or falcon.

4 Neanderthal Hunting Styles Dictated Their Art (And Fate)

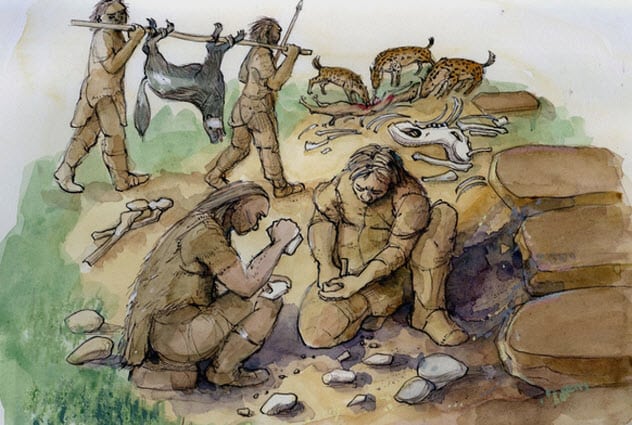

Neanderthals never attained the artistic realism achieved by their Homo successors, and it might (indirectly) explain why the Neanderthals died out. They had similar cognitive skills. As suggested by their hunting practices, they lacked the hand-eye coordination required for delicate art. In Eurasia, Neanderthals hunted horses, deer, and bison, which hadn’t developed a wariness toward early humans and could be speared from close range. But in Africa, Homo sapiens preyed on game that had already learned to be cautious. So Homo sapiens developed the tricky motor movements necessary to throw spears and kill from range. This newfound coordination resulted in a smarter, fatter brain and a finer artistic touch.[7]

3 The Ancients Kept Star Charts

What appears to be just another hunting scene could be the world’s oldest depiction of a supernova. Researchers found the tantalizing image, which shows hunters beneath two giant celestial objects, in a ruined house in Burzahom in the Kashmir Valley. The house dates to around 2100 BC, and the settlement was established in 4100 BC. So the mysterious supernova occurred within that time period. Since dead stars continue to emit X-rays long after going supernova, scientists were able to pin down the culprit, supernova HB9. It’s 2,600 light-years away, and its light would have reached Earth around 3600 BC. If the image is a star chart as researchers believe, its position lines up favorably, with the figures actually representing the constellations Orion, Taurus, and Pisces.[8]

2 The Thinker Is Several Thousand Years Old

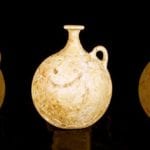

Archaeologists at a Bronze Age site in Yehud, Israel, found some basic funerary goodies—including daggers, arrowheads, and animal bones—offered to accompany a prominent Canaanite into the afterlife. They also found something way better, a ceramic jug topped with a clay figurine that resembles Rodin’s famous The Thinker. The 3,800-year-old statuette is considered historically unique. Along with some nearby Copper Age discoveries (in modern-day Jordan) like an irrigation system with terraced gardens, this suggests that an advanced civilization tamed this “fatally uninhabitable” land 6,000 years ago.[9]

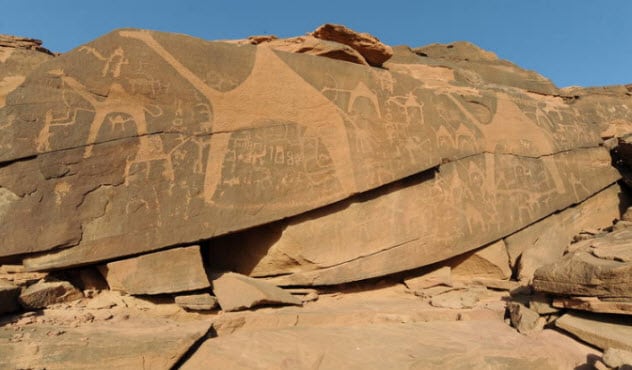

1 The Arabian Desert Was Once A Thriving Savanna

Like a millennia-old snapshot, petroglyphs can preserve an entire ecosystem. The art found in northwest Saudi Arabia captures a humid savanna full of unexpected creatures. With few earlier excavations and poor environmental conditions for preservation, researchers read the past via 250 stone etchings and identified 16 different species, which gradually disappeared from art as desertification spread. But between 11,000 and 6,000 years ago, the Arabian peninsula resembled East Africa rather than the desolate desert of today. As in Africa, lions, leopards, and cheetahs thrived here, feasting on plentiful large prey like gazelle and wild asses while fighting off hyenas, which were also abundant.[10]