10 Grampussing

Militaries are always tough on people who don’t perform their duties properly. Repelling an enemy attack can depend on a single guard keeping watch, so people who slack off have to be taught to respect their positions. An example of severe punishment for this offense can be found in the navy during King Henry VIII’s reign. Men who fell asleep on watch were given three strikes, with each strike ramping up the punishment. After the guard had fallen asleep for the fourth time, he was tied to the front of the boat in a basket and given food and a knife. The guard could choose to starve to death or cut himself free and land in the open sea. The punishment for the next offense involved a process known as grampussing. Although records on this punishment are scarce, King Henry VIII gave these orders to his navy: “The second time he shall be armed, his hands held up by a rope and two buckets of water poured into his sleeves.” When the water was poured down a man’s sleeves, he made a loud, gasping noise. This gasp was similar to the kind of sound made by a grampus (a kind of dolphin), which is how the punishment got its name.

9 Drunkard’s Cloak

Although some punishments were meant to harm the criminal, others were invented purely to embarrass the offender. That was the goal of the drunkard’s cloak, which was used as a punishment for public drunkenness during the 16th and 17th centuries. The offender would have to wear the drunkard’s cloak, a barrel with holes that allowed a person’s head and arms to stick out. The drunkard’s cloak wasn’t designed to harm the offender or otherwise impede movement. But a man walking around town wearing a barrel like a cloak was enough to teach him the importance of responsible drinking. The drunkard also had to pay five shillings to the poor. This tactic was so well received that it soon became a standard punishment in England. It began to spread across Europe as well. When Germany adopted it, they called it the schandmantel (“coat of shame“). A nastier variant called the Spanish mantle acted more like a pillory than a cloak. While the offender was held in the barrel, he’d have to kneel in his own waste and depend on others to feed him—if anyone was kind enough to offer food.

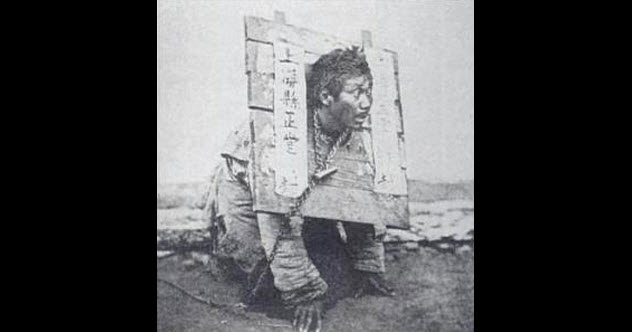

8 Cangue

In China, the cangue method of punishment was first mentioned around the 17th century. Cangue came in several forms, but they all shared the same general idea: The offender was placed in a wooden frame that locked his neck into place. Only his head appeared on the other side. The large frame prevented the offender from putting his hands to his mouth. Unable to feed himself, he was left to the mercy of others in his community to feed him and help him with daily tasks. Some variants of the cangue consisted only of the neck collar, which allowed the victim to move while wearing the device. The weight of the cangue was customized to match the crime. Some cangue were reported to weigh around 90 kilograms (200 lb), often causing the criminal to die from the stress. Another variant had a cage built around it, which kept the offender still. These cangue were often placed in public places. Some portable cangue could hold more than one criminal at a time.

7 Welsh Not

In 1847, a book by the British government reported that the Welsh educational system was doing poorly. The children were undereducated and unmotivated. They were also kept in bad conditions. The Welsh now refer to this book as the Treason of the Blue Books. At the time of the report, the commissioners decided that the only way to save the Welsh was to have them adopt English as their primary language. In school, Welsh children were only allowed to speak English. The punishment for those caught speaking their mother tongue was the Welsh Not. The Welsh Not was a wooden block with “Welsh Not” or “W.N.” etched into it. If someone was caught speaking Welsh, they were given the token. If the person who currently had the token caught someone else speaking Welsh, the first offender could pass the Welsh Not to the second offender. At the end of the day, the child with the Welsh Not was beaten. The use of the Welsh Not wasn’t governed by law. Each headmaster made his own choice as to whether to use this form of punishment on his students. Even so, permission from parents had to be given beforehand.

6 Treadmills

The treadmill, a 19th-century punishment used mainly in British prisons, was similar to the modern-day exercise machine. However, the prison treadmill looked more like a waterwheel than a moving floor and forced its user to perform a climbing motion rather than a running one. These treadmills weren’t designed as health machines. Instead, prisoners were forced to walk on them for eight hours per day with occasional breaks. The monotony and strenuous work was intended to deter prisoners from committing other crimes. Treadmills could also be linked to machinery. In Bedford Prison, the treadmills powered the production of flour. As this activity made money for the prison, the prisoner officially earned his keep. Over time, however, the linkage to machinery faded, and the treadmill became a simple punishment based on walking.

5 Trial By Ordeal

The trial by ordeal was a method of punishment known as judicium Dei (“judgment by God”). At a time when it was difficult to gather decisive evidence, people appealed to God’s will to determine a suspect’s guilt or innocence. The court would decide on the type of ordeal used to test the accused person. Supposedly, each ordeal could only be passed through a miracle from God. If the person did pass, it meant that God had spared the accused and that he was innocent of the crime. If he failed, God had forsaken him and he was guilty. Nasty examples of this type of punishment include the ordeal of the duel in which the accused had to make it through a fight. The ordeal of hot water required a person to dip his arms into hot water to retrieve a stone. If his arms were still scarred three days later, he was guilty. However, some ordeals didn’t need much of a miracle to pass. The ordeal of the cross had both the accuser and the accused stand in front of a cross with their arms outstretched. The first person to drop his arms lost the case. The ordeal of bleeding required a suspected murderer to stare at the corpse of the murder victim. If the corpse began to bleed again, the onlooker was the murderer. With the ordeal of the blessed morsel, the accused had to eat some blessed dried bread and cheese. If the person choked while eating, he was guilty.

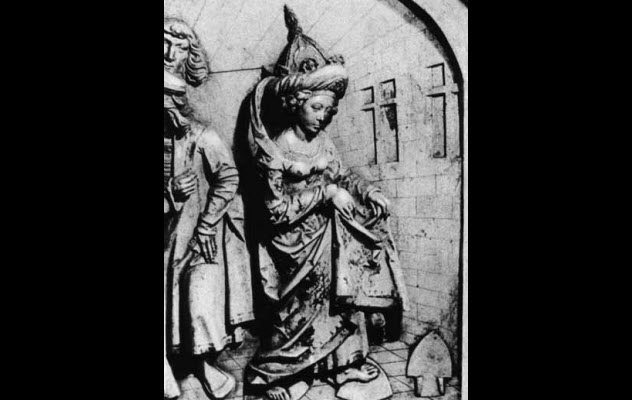

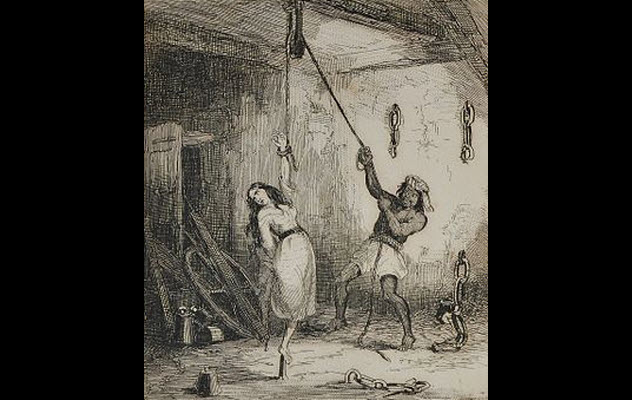

4 Pitchcapping

Pitchcaps were used mainly on people suspected of being rebels during the 1798 Irish Rebellion. The pitchcap was a conical hat created from any material close at hand, such as stiff linen. Boiling pitch was poured in the cone, and then the cap was forced onto the suspect’s head. When the hat was torn off, the hair and scalp went with it. Some methods added gunpowder to the hat and lit the gunpowder on fire after the pitch cooled. Although it was traditional for men to be bareheaded in church, it was said that Irish priests made an exception for survivors of pitchcapping, who were allowed to cover their scarred scalps with a handkerchief.

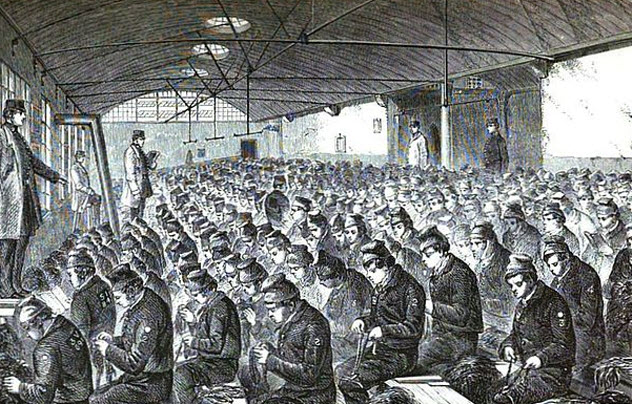

3 Oakum Picking

Oakum picking was another punishment that made ne’er-do-wells productive in prison during the 18th and 19th centuries. At the time, “junk” (old ropes from ships) was used to make oakum. The junk was cut into pieces and picked apart to create fibers called oakum. Then the oakum was mixed with tar to produce a sealing mixture that was placed in the gaps of wooden ships to make them watertight. Of course, the act of cutting up rope and manually picking out its threads was boring for prisoners. Although it was a useful punishment, some feared that prisoners were getting off too easy. In 1824, the authorities at one prison demanded that prisoners work a treadmill instead of sit and pick at rope. But some prisons stuck with this rope-picking method of punishment until iron ships began to replace wooden ones, which made oakum unnecessary.

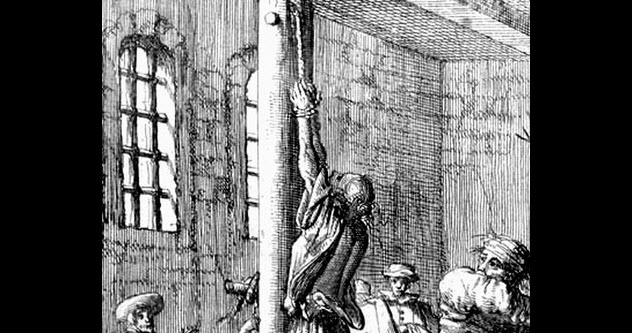

2 Picket

The picket (aka picquet) was often used for punishment in late medieval Europe, especially in the military. A stake was forced into the ground, and the flat end was sharpened to a rough point. The criminal was suspended above the stake. Records vary as to whether the person in question was hanging by his thumb or his wrist. Criminals were suspended at a height that allowed them to stand on the stake with a single foot. The stake was sharpened enough to cause discomfort but not to pierce the skin. The prisoner was supposed to stand on the stake until the pain became too much to bear. At that point, he could pull himself up to relieve the pain. But that solution caused pain in his wrist or thumb. The result was a “pick your poison” style of punishment which ultimately caused pain across the entire body.

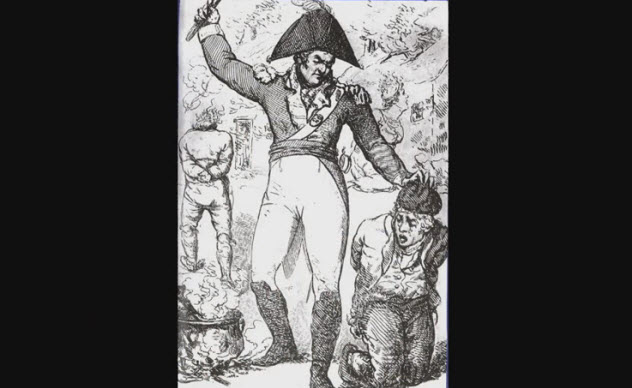

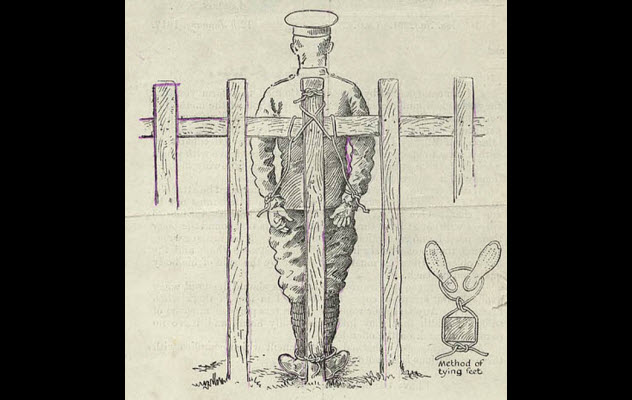

1 Field Punishment Number One

When flogging was abolished in the British army in 1881, officials had to think of new ways to mete out justice to those who were guilty of minor offenses such as drunkenness. One form of discipline was the strangely named Field Punishment Number One, which was used until 1920. The offender was tied up for several hours a day—sometimes to a wheel or post—with a military officer checking his posture every so often. During World War I, however, Field Punishment Number One was more than just mild humiliation. As one record from Private Frank Bastable demonstrated, this punishment could be life-threatening: When on parade for rifle inspection, after opening the bolts and closing them again the second time as it did not suit the officer the first time, I accidentally let off a round. I had to go before the CO and got No. 1 Field Punishment. I was tied up against a wagon by ankles and wrists for two hours a day, one hour in the morning and one in the afternoon in the middle of winter and under shellfire. S.E. Batt is a freelance writer and author. He enjoys a good keyboard, cats, and tea even though the three of them never blend well together. You can follow his antics over at @Simon_Batt or his fiction website at www.sebatt.com.