10Plague Art

It is impossible to understate the effect that the Black Death had on medieval society. Peaking in Europe somewhere between 1348 and 1350 with additional outbreaks in 1361 and the 1430s, the plague was a bacillus that could be contracted by the bite of an infected flea or rat or through the air, depending on the variety. The first wave of the Black Death killed an estimated 25–50 percent of Europe’s population. The plague made itself felt throughout medieval culture, where people found an outlet to express their collective despair and depression. Artists who had formerly painted joyous scenes depicting pious devotion or lofty illustrations of humankind’s achievements now turned to scenes of death and devastation. Religious themes also turned dark, focusing on the torments of hell and the wages of sin, increasingly turning their backs on the rewards of heaven or the comforts of ritual. It was in this macabre environment that several themes began to emerge revolving around death in early European art, not the least of which was the plague itself. Giovanni Boccaccio used the Black Death as the backdrop to his classic Decameron, a story about men and women who flee the city to a small villa in order to escape the plague. The delightful stories they tell while in hiding are a stark counterpoint to the devastation happening outside. Funeral procession scenes—already a common theme in art—were painted showing not famous kings or saints like before but anonymous plague victims as they were led to the grave. As more and more people began to see the plague as some sort of divine condemnation, the church stressed the importance of salvation through religious ritual and repentance as the proper means to combat the epidemic, an attitude reflected in works like the Limbourg brothers’ The Procession of Saint Gregory (1300) and James le Palmer’s 14th-century illumination for the Omne Bonum, which depicts plague victims receiving the blessings of a priest. Realistically-painted scenes of patients being treated in hospitals and at home were widespread, especially during the Renaissance. These were often accompanied by accurate depictions of the wounds and swollen pustules of the dying, such as in Jacopo Robusti’s St. Roch In the Hospital. (“Plague saints” were a genre in themselves.) The “death bed” scene, in which a dying person is ceremoniously surrounded by loved ones, dates from the Black Death period in the 1400s. There was also a trend toward depicting sculptural figures on tombs as actual corpses, often bearing signs of the plague or even fully skeletal, instead of idealized portraits of the deceased. As death became a grim reality and heaven a faraway abstraction, realism made a great comeback within European art. These are just a few examples of how the Black Death had a direct influence on the art of the Middle Ages through the Enlightenment, which inspires us to this very day. In 1988, avant garde diva Diamanda Galas released the first record in her Plague Mass trilogy, Masque of the Red Death, a Black Death–inspired look at the AIDS epidemic that was surely recorded in hell.

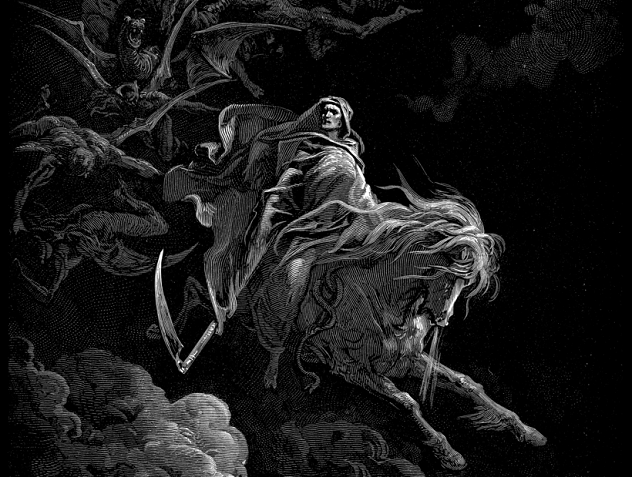

9Death As A Reaper Of Souls

All cultures in all times and places have personified death in one form or another. To us modern-day people, one of the most immediately recognizable personifications is the Grim Reaper. Nowadays, he’s mostly found on heavy metal album covers or goth jewelry, but to the medieval world, he was an authentic figure of terror. The idea of death as a reaper holding a scythe that he uses to harvest souls is a 15th-century invention that drew upon many earlier sources. Inspirations from Greek mythology included the Titan named Kronos (whom the Romans might have confused with Chronos, the god of time) and the boatman of the river Styx in the underworld named Charon. Before its modern form was fully developed in Europe, death was usually portrayed as a corpse holding a crossbow bolt, dart, bow, or some other weapon. It was during the plague that Europe began portraying death as a skeleton wielding a scythe and wearing a black (or sometimes white) robe. He was usually portrayed as a guide who would appear at the subject’s appointed hour to lead them away, although in later tales, he actually took life himself, and victims could cheat or bargain with him. Death as a reaper can be found in every form of art throughout Europe. He has appeared in plays, songs, poetry, romantic literature, and bawds. He cavorts through the darker paintings of Breugel and is often the figure of “danse macabre” art. In sculpture, a 17th-century statue of a bishop in Germany’s Cathedral of Trier accompanied by the Grim Reaper serves as a great example. While the Bible never portrayed death as a reaper, many artists from the 15th century onward used the motif in biblical art. Gustave Dore’s engraving of Death on a Pale Horse (1865) is a particularly dramatic example.

8The Dance Of Death

A belief developed throughout the plague years that the dead could rise from their cemeteries and draw any unlucky passersby into a ghoulish dance of death. These folkloric beliefs, fueled by period poetry about the inevitability of death and a traditional dramatic play enacted in Germany, quickly found their way into European art as a societal allegory about mortality, which gained widespread popularity. The message is clear in the danse macabre—nobody escapes death, so it’s wisest to prepare your soul for its time of reckoning. The danse macabre portrayed the hierarchy of classes, from pope to commoner child, engaged in daily routine as they were forced into death’s waiting arms. One of our earliest pictorial examples is from a series of paintings created in 1424–1425 and formerly displayed in the Cimetiere des Innocents in Paris. The originals were destroyed in 1669, but Paris printer Guy Marchant preserved their essence in a series of woodcuts along with the verses that accompanied them. The motif reached its ultimate expression in Hans Holbein the Younger’s woodcuts and verses The Dance of Death. It was first published in 1538 as a book with 41 woodcuts, while later additions in 1545 and 1562 brought this count up to 51. The entire text, as well as all of the woodcuts, can be found online here. Another fantastic example, this one in painting, is Bernt Notke’s Danse Macabre. It was destroyed during bombing in World War II, an event that was considered a great loss to art.

7Dance Of The Skeletons

Another theme related to the dance of death is the dance of skeletons, which we know primarily through a woodcut by German humanist and early cartographer Michael Wolgemut that appeared in Liber Chronicum (“The World’s Chronical”), a book written by Hartmann Schedel and published in 1493. The dance of skeletons is different from the dance of death in that it is strictly based on folklore, with no social or moral message. Skeletons are usually depicted coming forth from open graves, cavorting about, and often playing music and dancing. Wolgemut’s woodcut is a beautiful example of the genre, which was used to illustrate and thrill rather than educate or preach to the viewer. The skeleton dance was a short-lived theme in early art, with few surviving examples. In more recent times, it cropped up in music when Camille Saint-Saens based his 1874 Danse Macabre on the dance of death and skeleton dance themes. In film, Walt Disney and Silly Symphonies revived the theme in 1929 in the immortal and often-imitated short cartoon “The Skeleton Dance,” in which four skeletons dance around a cemetery and terrorize the living residents.

6Anamorphosis And Hidden Symbols Of Death

Anamorphosis, which means “the image within the image,” is a technique sometimes employed in art to create hidden imagery that can only be seen properly from certain angles or under the right conditions. It was first seen in Europe in 1485, when Leonardo da Vinci used it to depict a human eye. Several artists have incorporated anamorphosis into themes of death, the most famous example of which is Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors (1533). The painting is a double portrait of Jean de Dinteville, French ambassador to the court of Henry VIII, and his childhood friend Georges de Selve, the Bishop of Lavaur who also acted as an ambassador on several occasions. It was painted in the early years of the Reformation and is rife with political and theological symbolism on those themes, but the most jarring element is a strange, elongated oval shape at the bottom of the painting, which resolves itself into a skull when viewed with the eye at a position near the bishop’s hand. One of the purposes of this hidden skull was to remind the powerful players involved in the troubles of this time to be humble and mindful of their mortality. Anamorphosis and other forms of hidden images have been used throughout the history of art since Da Vinci’s day. A later example is Charles Allan Gilbert’s All is Vanity (1892), in which a Victorian-era lady admires herself in a mirror that, with a shift in vision, turns into a skull. You can find a contemporary example of death-themed anamorphosis in the work of Hungarian artist Istvan Orosz, who creates illustrations with a medieval woodcut feel that always hide a skull.

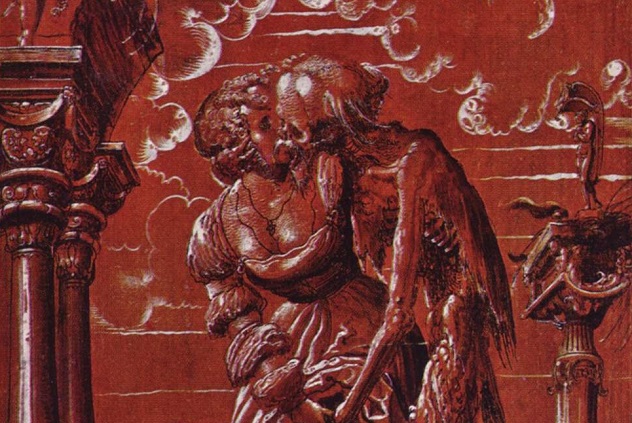

5Death And The Maiden

The theme of death and the maiden can be traced all the way to ancient Greece and the story of Persephone, who was kidnapped by Hades and brought to the underworld after picking the narcissus flower. One of its themes is familiar—that death overcomes all, even the proud beauty of women—but in the 15th century, the theme began to gain unique features and became overtly sexual. The women embraced in the arms of corpses or skeletons were now engaged in an intimate intercourse with death. Between Niklaus Manuel Deutsch’s Dances of Death and Death and the Maiden (1517), we can actually see the transition. In the former, death dances with an elegant lady, placing both bony hands firmly on her breasts. In the latter, Death is no longer dancing—he is embracing her fully, forcefully kissing her as his hands go to her genitals. The maiden is trying to resist but helpless to do so. This strongly erotic imagery, sometimes used by artists to justify paintings of nudes to the church, was used again and again throughout the 15th century and beyond. One painting in a series painted between 1518 and 1520 by Hans Baldburg Grien depicts a Madonna-like nude figure grasped by a desiccated corpse while sperm and fetuses, which were symbols of the renewal of life, revolve around them. This symbolism would be used again by Edvard Munch in his Death and Life (1894). One of the most powerful modern examples is a drawing by German avant garde artist Joseph Beuys. Created in 1959, it depicts death and the maiden on an envelope bearing the stamp of an organization of Holocaust survivors. In this drawing, both death and the maiden are insubstantial and desiccated, a testament to the fleeting nature of life and the cheapness of death in that cataclysm. A similar death-related theme that rose up in art of the period is called “the three ages of man,” although it usually depicted women. A figure is shown in succession as a child or newborn, a young adult, and finally, a middle-aged woman, where death stands to lead the subject offstage to the underworld. A good example is Grein’s The Three Ages of Man and Death (1510).

4Triumph De La Mort (The Triumph Of Death)

Much more disturbing than the dance of death, the “triumph of death” motif was another theme that was common among medieval artists. Like the dance, the underlying message was that mortality is inevitable, but unlike the “dance,” the “triumph” theme depicts death as an instrument of chaos and destruction, a brutal dictator whose minions sweep over everything, destroying all in its path. It was especially associated with times of war and plague. This theme dates back to at least the 1400s, as it was already a widespread idea when an unknown artist painted a fresco in the court of Palazzo Sclafaniin, Palermo in southern Italy. The Triumph of Death (1445) features a bow-wielding skeleton riding a skeletal horse and shooting arrows at his targets, medieval villagers of all walks of life going about their daily routines. The undisputed masterpiece of this theme is The Triumph of Death (1562) by Pieter Bruegel the Older. In the painting, a once-peaceful medieval village becomes reduced to an apocalyptic wasteland by an army of reapers and corpses. It is like Bruegel obliterated every one of his medieval scene paintings in one canvas. Literally hundreds of depictions and symbols of everyday life run through the painting, each one a little morality play whose thesis is death. Even a king gets no reprieve. A corpse displays his hourglass, running out of time, and the king succumbs as another armored corpse helps himself to his collected wealth. All is lost. All is futile. Death always triumphs in the end. The Triumph of Death is widely considered one of the most important paintings of its time. A Wall Street Journal article noted that “The brutality of these images has given Bruegel’s picture a woeful and continual relevance. It seems to anticipate descriptions of the Thirty Years War in the 17th century . . . Most disturbing from a 21st-century perspective are what appear on the right of the picture to be rectangular containers where humans are forced inside and sent to their deaths. The devices’ similarity to Nazi technology of mass extermination has struck many viewers.” As long as there is war, famine, pestilence, and death itself, Bruegel’s masterpiece will continue to be a painting that disturbs us even as it resonates.

3The Grateful Dead

The motif of the “grateful dead” is rare in pictorial art, more commonly associated with folklore and literature. Legends about the grateful dead revolve around two basic themes. In the first, someone performs a service or favor to someone who is dead, such as taking care of unpaid debts or paying for a funeral service, and is rewarded in some way by its spirit. In the second, someone in dire need of aid enters a cemetery and prays for help. The dead then rise from their graves to assist the living. The former dates back to Old Testament times with the apocryphal Book of Tobit. It was later picked up in literature, most notably in the medieval romances. The latter can be seen in a fresco called The Legend of the Grateful Dead, painted in Switzerland by an unknown artist in the early 16th century and restored in 1740. It depicts a man being chased by a band of thieves into an unconsecrated graveyard, where he kneels to pray. Before the murderous thieves can reach him, the graves around him erupt with the corpses of the dead who rush to defend the man with sticks and scythes, thankful for the prayers that will allow them to rest in peace. The message of the grateful dead stories is much different from most death-related themes of European art, perhaps because memories of the plague were receding and more people were allowing themselves to be positive about the future. They reminded the living to think of their loved ones and keep them in their prayers and to remember those who were gone.

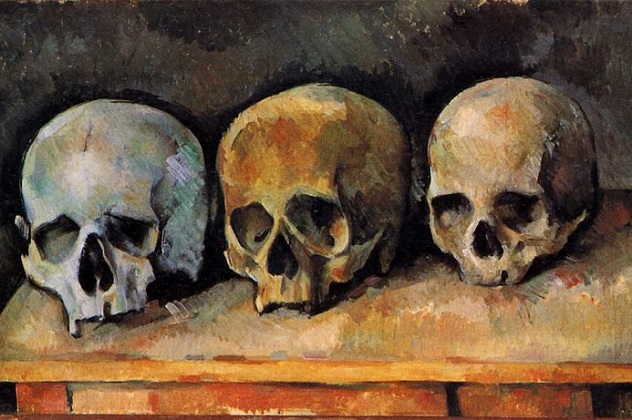

2Skulls In Art

Perhaps no other icon has had such a universal impact on symbolism and art than the human skull. Its symmetrical features are visually appealing to the eye even as its obvious association with death fascinates and repels at the same time. Virtually every culture has made use of it, most often as a symbol of mortality but sometimes as an affirmation of life, such as Mexico’s use of skulls and skeletons during Dia de los Muertos (“Day of the Dead”) festivals. The skull is often incorporated into still life paintings along with other related objects. Sometimes, it was used somewhere in a painting as an intimation of death or painted onto the backs of portraits to serve the same purpose. A skull might also be used as a replacement for the actual subject in a portrait if that person was dead. In the Braque Family Triptych (1452) by Dutch painter Rogier van der Weyden, a skull is depicted not only as a memento mori but a depiction of the patron, whose accomplishments are symbolized by the brick and family crest also shown. The skull was a common feature of jewelry even in the Middle Ages, as upper-class men and women alike wore medallions that were engraved with faces on one side and skulls on the other as a reminder of death and the obligation to lead moral lives. Because of their aesthetic appeal, skulls were often used for non-symbolic and purely decorative purposes as well. Cezanne’s The Three Skulls (1900), one of several paintings he did of the subject, combines elements of impressionism and expressionism, creating complex interactions of light and form that have technical and emotional meaning but without the emphasis on symbolic meaning that characterized earlier Western depictions of skulls. By the 18th and early 19th centuries, the skull had become a symbol of pirates and then rakes, ne’er-do-wells, and outlaws. This use continues today, as can be seen in the fashion and jewelry of bikers, punk rockers, and other anti-authoritarian subcultures.

1Anatomy As Art

In 1697, Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch so impressed Peter the Great that the Russian tsar bought the entire collection of his work from Ruysch’s anatomical museum. Anatomical displays of preserved human and animal corpses and skeletons were not new, and neither were the kind of admonitory captions often placed on plaques to describe the scenes, but what made Ruysch’s work unique was that he did his best to portray the beauty of anatomy and death. With the Renaissance in full swing and the memory of plague receding, the flowering of modern science brought with it new attitudes toward death and dying. Death could be seen as a cycle again, a counterpart to life that was just as important and poignant. Ruysch sought to capture those ideals in his work, which combined embalming techniques with sculptural and painterly concepts to create works that incorporated mummified children and preserved fetuses and skeletons with still life and artistic embellishments that were created with other anatomical details, including trees and bushes formed from human arteries and rocks formed from kidney stones. Ruysch continued his work through the 17th century. Sadly, none of his dioramas survive today, although a few decorated babies preserved in jars do still exist. We know of them thanks to the work of engravers, chiefly Cornelius Huyberts, who published them in the Thesaurus Anatomicus. Lance LeClaire is a freelance artist and writer. He writes on subjects ranging from science and skepticism, atheism, and religious history and issues to unexplained mysteries and historical oddities, among other subjects. You can look him up on Facebook or keep an eye for his articles on Listverse.