Looks, however, can be deceiving when it comes to something as apparently complicated as death, leading to prisoners unknowingly choosing the manner in which they will be tortured. Whether or not you agree with the death penalty isn’t the point—the point here is that even when you’re in charge of your own fate, you can’t control the tragedy of errors that an execution can turn out to be. So, for those of you that might find yourself in such a position as to be forced to decide how you’re going to die, reflect for a moment on how some other people were helped from this world before you make the ultimate decision.

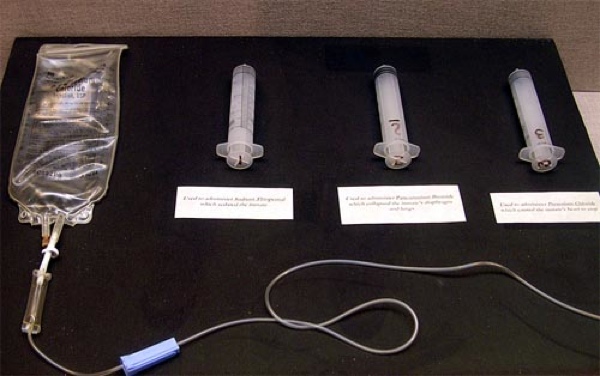

Christopher Newton was a man with some pretty severe problems. Having intentionally gotten himself arrested for burglary so that he would be imprisoned, Newton decided that prison was exactly where he wanted to die. Under the pretense of being threatened by fellow inmates, the 6 foot (182.8 cm) 265 pound (120.2 kg) man was placed in a cell with 130 pound (58.9 kg) inmate, Jason Brewer. If this doesn’t seem automatically alarming to you, don’t worry—the warden didn’t see anything wrong with it, either. After getting his way, Newton would enact the first part of his plan by brutally murdering his new cellmate after the man kept giving up during chess games. It seems petty, but when all you have in life are chess and seductive photographs of Macaulay Culkin, your mind begins to do strange things. Regardless of his true motives for the murder, Newton was unsurprisingly placed on death row to be executed by lethal injection. When the time came, though, not quite everything went to plan. First off, it took about an hour-and-a-half to find a suitable vein in which to administer the cocktail of chemicals due to his weight. During this time, he was stabbed a minimum of ten times with needles, and was even permitted a bathroom break because of the sheer amount of time taken. Finally, when the needle was properly inserted, witnesses report that Newton’s stomach heaved, his chin and mouth twitched and he suffered at least two mild convulsions on the gurney, all of which should have been impossible if the injection was administered properly. Further adding to the debacle, it took Newton a full sixteen minutes from the time the drugs began flowing to the time he was declared dead. That’s about double the time it normally takes for lethal injections to kill the condemned.

Brian Steckel might as well be synonymous with being a despicable human worthy only of death. Given the nature of his crime, it’s difficult to find a valid reason for keeping him alive. However, capital punishment is intended to be humane—something it was not in his case. It began when Steckel knocked on twenty-nine year old Sandra Lee Long’s door and asked to use her phone. Upon being allowed into the premises, his demeanor rapidly changed as he propositioned the woman for sex. Of course, she refused him. This sent him into a rage, at which point he strangled her with a pair of tights. Half-conscious from the attack, Sandra was unable to defend herself as Steckel sexually abused her with a screwdriver, then raped her from behind. Unsatisfied with just this, Steckel then decided to set her on fire, which was ultimately the cause of her death due to smoke inhalation and severe burns. All of that is certainly bad enough, but Steckel managed to up the ante by sending taunting letters to Long’s mother during his trial. In spite of all of this, when it came time to execute Steckel, the procedure should have been carried out quickly and humanely. But he execution was anything but quick, as the lethal injection machine sat and clicked for about twelve minutes while Steckel remained conscious and lucid throughout. Determining that the main IV line was blocked, the machine was switched to the backup line, though the sedative drug was not administered, and Steckel continued to stay conscious as the paralytic pancuronium bromide took effect. The heart-stopping potassium chloride was then injected, excruciatingly killing Steckel with a sensation described as “having your veins set on fire,” all while he was unable to move or react to indicate the kind of pain he was experiencing. A fitting end for one so fond of murder by fire, I suppose.

In 1890, William Kemmler was convicted of violently murdering his common-law wife with a hatchet and sentenced to death via electric chair. What makes this special, is that William was to be the very first man in the world to die in this manner, so of course nothing would go wrong. Placing a childlike trust in his soon-to-be executioners, Kemmler did what he could in order to assuage their nervousness . . . Yes. Their nervousness. This including assisting in his own restraint and offering some words of encouragement to the warden and his deputy: “Take your time; don’t be in a hurry. Do it well; be sure everything is all right,” he said. “It won’t hurt you, Bill,” the warden replied, “I’ll be with you all the time.” The warden probably believed his own words as much as his prisoner did, but this was 1890, and they were attempting to painlessly kill a man using electricity. But it worked well enough on their equine test subject, they reasoned, so how could it not succeed on a much smaller man? Upon finishing up with the preparations to begin the execution, the warden gave the signal to flip the switch and was obliged almost instantly. Kemmler’s body became rigid with the current flowing through it, and by the end of the ten second mark, everything seemed to have gone according to plan: Kemmler was declared dead. As the warden and doctors started to wrap up the execution with a businesslike discussion about the preceding events, one of the doctors noticed a cut on Kemmler’s hand that was caused by a piece of the equipment rubbing against it. The wound, by all appearances pretty inconsequential, happened to be bleeding—strongly indicating that William was still alive. The warden, panicked by the apparent blunder, quickly ordered the current to be restarted in order to finish the job. By this point, fluid seeped from Kemmler’s mouth and ran down his beard as he began to groan repeatedly and increasingly loudly. It was clear that the condemned man was beginning to regain consciousness, which caused even seasoned doctors to turn their heads and pale. At last, after what seemed like ages to all those involved, the electricity was restarted and Kemmler once again convulsed, ceasing the noise coming from his lips. It was almost a relief to watch as the man died, but then came a sickening sizzling sound from the chair, as if meat was being cooked upon it, followed by a billow of smoke that filled the room with the odor of burning hair. And it’s with these mental images that we can best remember the advent of the electric chair; a horrifying spectacle that went on to become one of America’s most commonly practiced methods of humane execution.

On parole for the murder of his girlfriend, Gray abducted a three year old girl, sodomized her, attempted to drown her in a creek, and then finally finished her off by stomping on the back of her neck, breaking it. The executioner was fully aware of Gray’s crimes and expressed his opinion on the man by calling him a “sumbitch,” describing the crime, and then sarcastically stating: “So yeah, I feel really sorry for Jimmy Lee.” There’s a reasonable chance that the execution was intentionally botched so as to cause as much suffering as possible to Gray. Having been sentenced to die in the gas chamber, Gray sat in the death chair as the cyanide crystals were dropped into a dish beneath him containing sulphuric acid and distilled water, creating the lethal gas. As the gas reached his lungs, he began to choke and gag for about eight minutes, to the horror of the witnesses. After this initial horror-show, Gray’s unrestrained head began to smash into a steel pole placed directly behind the death chair. This was enough for the warden, so he prematurely cleared the witness room to spare them having to watch the gruesome display of a suffocating man slamming his skull against the hardest object in the vicinity. Witnesses reportedly counted eleven groans from the dying man before being mercifully ushered out of viewing range. The prison maintained that Gray had died painlessly and was brain dead by the time he began his self-destructive episode.

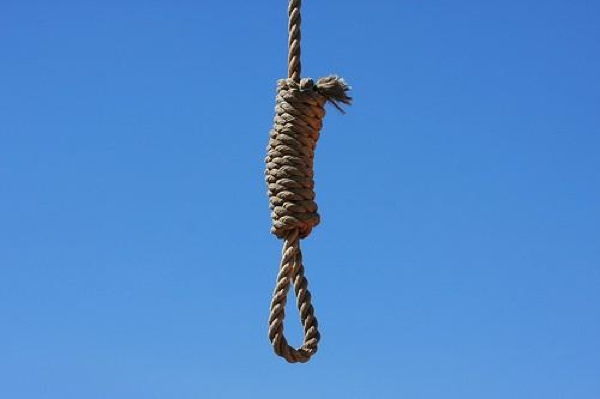

Convicted of murdering his girlfriend in 1891, Painter was sentenced to be hanged three years later for the grisly crime in which the woman was strangled, and her head beaten against a bed post until she was dead. If Painter, who maintained his innocence until the end, had been the true murderer (multiple witnesses came forward in Painter’s defense but were dismissed as unreliable), he had attempted to make the scene look like a burglary by pulling down his lover’s left sock—a known hiding place for money amongst women of her class. But, despite who may have been the killer, George would be the one to pay for the crime with his life. On January 26th, 1894, Painter was walked to the gallows in front of about seventy spectators and allowed to speak his final words: a low, trembling assertion of his innocence and a desire for the real killer to be found. A white hood was then placed over Painter’s head and drawn closed with a string, and his thighs bound by straps. The noose was then presented and placed around George’s neck as the men preparing the condemned stepped away from the trap door. Given the signal, a man in a concealed box cut the rope and the trap door below Painter swung open with a bang, dropping his body through. The rope supporting Painter’s weight became taut, then, as the crowd breathed a collective gasp, snapped and sent the man’s body hurtling to the solid ground in a heap. Jailers rushed to carry Painter’s body back up to the platform where doctors confirmed that his neck had snapped, but did not believe him to be dead. While the jailers cut the rope from his neck and replaced it with a new one, spectators were aghast at the sight of the white hood becoming red in color as Painter’s head began to bleed profusely. Now in a sitting position upon the trap door, blood poured down George’s body, staining his white gown the same crimson shade as his hood, prompting some spectators to flee the room. The trap door was then sprung once more, and Painter’s body took a second, final plunge, after which he was pronounced properly deceased.

During the 1720s, French authorities had just executed the ringleader of the then-infamous Cartouche gang and were busying themselves with rounding up and executing the rest of the members of the bandit collective. Louison Cartouche, a member of the gang and younger brother of the aforementioned ringleader, was already condemned to hard labor in the wake of the crackdown when a judge by the name of Arnould de Boueix decided to use the young man as an example to would-be criminals. The punishment, however, was a bizarre-as-hell one: fifteen year old Cartouche was ordered to be hanged by his armpits for two hours, the act apparently intended as a humiliation rather than an execution. The judge, of course, had no cause to believe his dreamt-up punishment would not be fatal, as there was currently no precedent for hanging someone under the arms for hours on end. So, on the judge’s word, the punishment was carried out in 1722, with Cartouche crying out in agony early into the hanging. The boy begged for his sadistic captors to put him out of pain, but he was denied and continued hanging as the blood in his body was forced downward to his feet causing incredible pain. Finally, his tongue lolled from his mouth, and his agonized pleas ceased. Though the two hours had not yet expired, Cartouche was taken down and placed in medical care, where it was determined that the boy was well beyond help and declared dead. And so it goes that a non-fatal humiliation became an excruciating death by nothing less than torture.

Lady Margaret de la Pole was an aristocrat of high standing during King Henry VIII’s thirty-eight year reign over England. Despite her relation to the king (her cousin, Elizabeth of York, was Henry VIII’s mother), the sixty-seven year old Margaret was accused of treason in place of her son, Reginald Pole, who had imposed a self-exile on himself and remained in France and Italy, out of reach of the English king. Her punishment, beheading by axe, would be the king’s revenge for her son’s denunciation of the king’s policies, which included Henry’s interpretation of the Bible’s stance on marrying a brother’s wife, denying the Royal Supremacy. Furthermore, Reginald was unwilling, at the king’s request, to support his separation from Queen Catherine and subsequent marriage to Anne Boleyn. But the icing on the cake had to come in the form of a highly treasonous call for the princes of Europe to depose Henry. The sexagenarian Margaret, never seeming to have a treasonous thought of her own, spent the next two and a half years imprisoned in the Tower of London, before finally facing the day of her execution. Guilty of no crime, Margaret was one day awakened from her sleep and told she was to be put to death within the hour, but naively protested on the grounds that she had done nothing wrong and no evidence existed to prove otherwise. This protestation, of course, fell upon deaf ears as she was later led out to the scaffold, in front of about 150 witnesses. Told to place her head on the chopping block, Margaret sternly refused and the frail woman had to be forced into position. As she struggled, the inexperienced executioner, who was by now panicking, swung the axe to deliver the single required blow to her neck. Almost predictably, the axe failed to land a fatal strike and instead buried itself in the elderly woman’s shoulder. The axeman then had to deliver several more inaccurate strokes, imbedding the axe variously in the woman’s head and upper body before finally delivering a life-ending blow that ceased her agony. Some reports suggest that Margaret ran about screaming and had to be hacked to death by the executioner who was seemingly playing the part of Wile E. Coyote. These versions of the event are most certainly fabricated, though some of the descriptions can be morbidly comical.

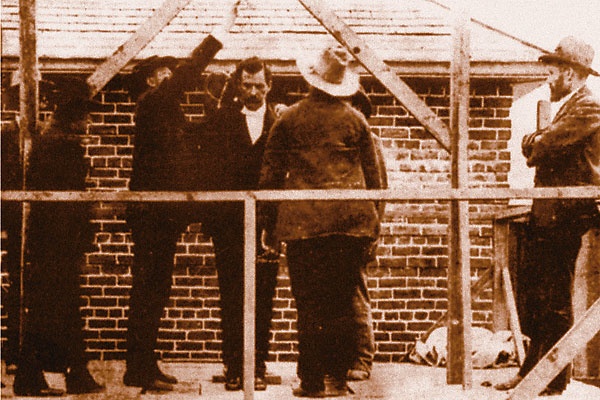

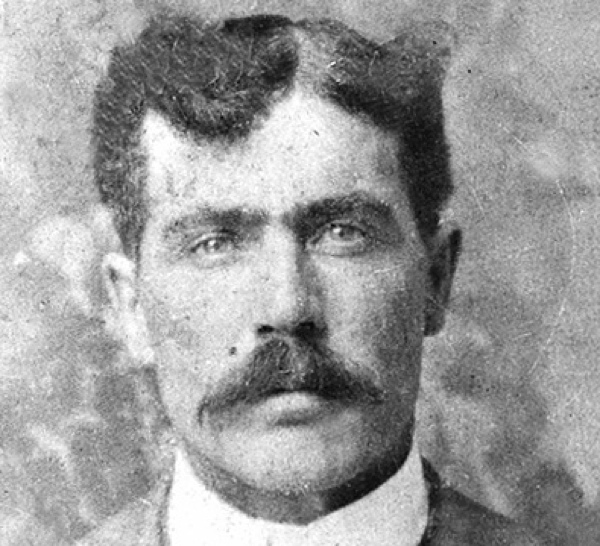

An American outlaw who operated in Texas and New Mexico during the latter portion of the Wild West years, Thomas Ketchum was a sordid kind of fellow with little regard for human life or charity. Little seems to be known of Ketchum’s life between his birth in 1863 and the beginning of his criminal career in 1890, so it’s likely that he was on the straight-and-narrow up until about that date, when he inexplicably (perhaps after committing a crime) left Texas for New Mexico. For two more years, he worked as a cowboy, flying cleanly under the radar until his involvement in an armed train robbery. It’s believed that after the heist, in 1896, he may have been party to the disappearance of a man and his eight year old son, neither of whom were ever found. Several years ticked away with Ketchum joining the Hole-in-the-Wall gang and performing more train heists and other unsavory deeds. During one of these robberies in 1899, he was struck by a shotgun blast and had to have his right forearm amputated, after which he was moved from the medical facility to Clayton, New Mexico to face trial where he was convicted of ‘felonious assault upon a railway train’ and sentenced to hang. Two more years passed with Ketchum in custody until the date of his execution in 1901. Never having hanged a man in Clayton before, the procedures for doing so were unfamiliar and those involved with the execution were forced to improvise, which generally doesn’t turn out so hot. The rope, much too long for a man of Ketchum’s size, was also particularly thin and cord-like, which did not bode well for him. Noose around his neck and standing upon the trap door, an eternity seemed to pass for the man until his sudden drop. The rope went taut, and to the horror of the large crowd of witnesses, reporters, and gawkers, Ketchum’s body plummeted directly into the ground. Not to worry, though: the execution was a success with his head being torn clean off of his shoulders, prompting an eruption of blood from the corpse’s neck. To this day, postcards are sold in Clayton depicting the gruesome aftermath of the bungled hanging, which pretty much seems to be the town’s only claim to fame.

Wallace Wilkerson was born in 1834 in Quincy, Illinois, before moving to Utah with his family at the age of eight. At seventeen he worked as a stockman and repeatedly enlisted in the military, one time serving as a drummer in San Francisco. Around 1877, he found himself frequenting a nearby saloon that was tended by a man named William Baxter, who once had to break up a conflict between Wilkerson and another patron by using a revolver to settle them down. As luck would have it, that same year fate conspired against Baxter when he wound up running into Wilkerson at another saloon and the two decided to play a game of cribbage for money. As with most stories about card-playing in the 1800s, this one also took a turn for the worse with accusations of cheating. Baxter attempted to back out of the argument, but Wilkerson was having none of it and planted a bullet in the man’s forehead, then his temple. It later turned out that Baxter was unarmed at the time and Wilkerson was tried and convicted for premeditated murder. The execution date was set for later that same year, and Wilkerson chose his method of death to be execution via firing squad, rather than the alternative options of being hanged or decapitated. On the day of his death, Wilkerson was permitted to spend his remaining hours with his wife, during which time he must have gotten his hands on some alcohol, according to witnesses who saw him in his final moments. When he was at last taken from his cell, Wilkerson was dressed in black with a white felt hat and a cigar that he kept during the execution. The condemned man was then seated on a chair about thirty feet from the shooters as a blindfold was prepared for him. Wilkerson, however, declined to wear the blindfold, stating “I give you my word . . . I intend to die like a man, looking my executioners right in the eye.” Restraints, too, were eschewed at the word of the prisoner as a small white square was pinned over the man’s heart by a marshal. Wilkerson took a deep breath and drew himself up straight in the chair in anticipation of the volley. This action, unbeknownst to Wallace, moved the target several inches upward as the executioners fired their salvo at him. One bullet shattered his left arm, while the rest punched into his torso, failing to instantly kill the man. Wilkerson, meanwhile, leapt from the chair and hit the ground screaming “Oh my God! My God! They have missed!” Four doctors rushed to him amidst concerns that the executioners might have to shoot him again, but the worries were unfounded: Wilkerson bled out from his wounds just twenty-seven minutes after receiving them.

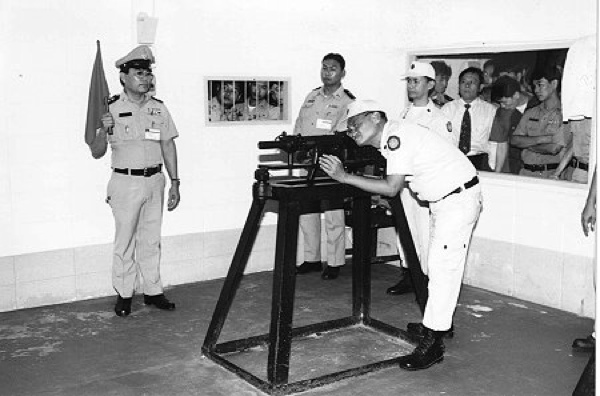

A mouthful, and certainly difficult to type, Ginggaew Lorsoungnern was a former domestic for a Bangkok family. Using her familiarity and the trust established with the family that once employed her, she picked up their six year old boy from school and personally delivered him to a Thai kidnap gang, who then demanded a ransom from the child’s parents. The parents complied, following the plan to hurl the money out of a moving train and close to a designated flag. Unfortunately, because the delivery occurred at night, the parents were unable to properly see the flag and missed the exact spot. Assuming the ransom was denied, the infuriated kidnappers proceeded to stab the young boy to death, at which point it’s alleged that Lorsoungnern flung her body over the boy’s and attempted to shield him. This act, assuming it happened at all, failed to save the boy who was then dumped into a grave. Another sad discovery came later, when the coroner found soil in the child’s lungs, indicating that he was still alive at the time of his burial. For her role in the boy’s murder, Lorsoungnern was sentenced to death by shooting, an execution in which the condemned was tied to a wooden cross, with their hands bound in a praying position and their bodies facing a wall. Behind them, a screen was set up in which a target was drawn, indicating where the heart was. The executioner remained behind this screen, unable to see the prisoner’s body, and operated a mounted automatic rifle which would deliver fifteen or so bullets to the vicinity of the heart. The sheer amount of bullets striking such a vital region would typically ensure that death came instantly, provided the target did not struggle too much. On the day of her death, January 13th, 1979, Lorsoungnern succumbed to repeated fainting spells, and had trouble standing under her own power. The escorts had to keep reviving her with smelling salts as they approached the execution room while she continued to maintain her innocence in the boy’s murder. “I didn’t do it, I didn’t kill the boy,” she begged. “Please don’t kill me, I didn’t kill him.” Her desperate words fell upon deaf ears as the escorts finally managed to lead the woman to the cross and began to secure her to it. At last, the gun was loaded and the executioner took aim. A moment later ten bullets were consecutively fired into the screen. Shortly after the shots were fired, a doctor approached the woman and checked for vital signs, none of which were found. Lorsoungnern was, by this point, bleeding profusely as they untied her body and laid her face down on the floor where she jerked and twitched slightly. Her chest had burst open from the bullets. Her body was moved to the morgue and placed upon a bed as they readied the next person for execution. It was then, however, that Lorsoungnern began to utter sounds and attempt to sit up. The escorts rushed into the morgue, one of them rolling her over and pushing down on her back in an effort to help her bleed out quicker. Another attempted to strangle her, but was stopped. She laid there gasping for breath as one of the men who had a part in her crime was executed and died instantly. Still, after this time, she continued to breathe and was ordered to be tied back on to the cross. The escorts became covered in her blood as they tried to hoist her back into position. Finally, fifteen more bullets were put into her body and she was mercifully pronounced dead. The reasons for her unenviable death are as follows: she was not tied tightly enough to the cross, and could therefore wriggle out of position, and her heart happened to be on the right side of her body instead of the left.