But there’s more to Charlie Hebdo than simply caricaturing Islam’s prophet. Throughout the years, they’ve targeted just about everyone.

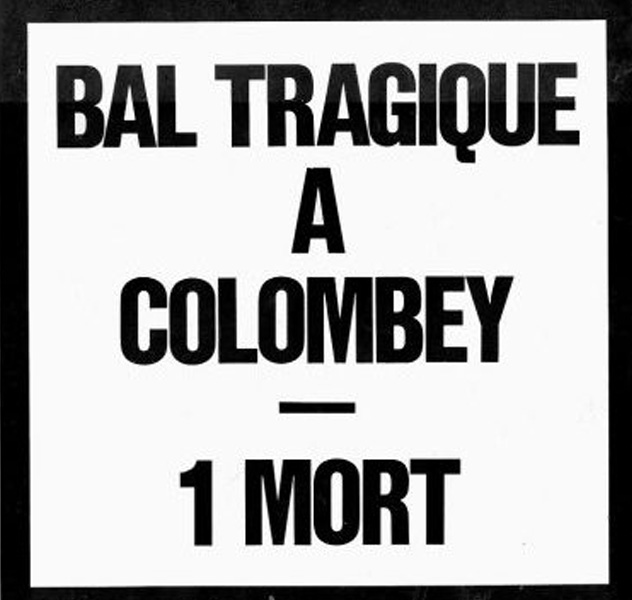

10The Death Of De Gaulle

Before it became Charlie Hebdo, France’s most controversial magazine was known as L’Hebdo Hara-Kiri. Hara-Kiri had one mission only: to be as “dumb and nasty” as possible (their words). It achieved this spectacularly in 1970 with the death of Charles de Gaulle at his home in Colombey. Eight days before de Gaulle passed away, a devastating fire had swept through a nightclub in Saint-Laurent-du-Pont. The death toll was 142 teenagers, and many of the survivors had severe burns covering 90 percent of their bodies. It was a hideous, immeasurable tragedy that would have defined the year in news had France’s elder statesman not passed away soon after. With his passing, the fire vanished from headlines . . . until Hara-Kiri hit the newsstands. In English, their cover read: “Tragic Ball At Colombey: 1 Dead” (original shown above). It was like setting a firecracker off underneath the French establishment. A furious government banned Hara-Kiri from sale, claiming that the headline was tasteless and offensive. It wasn’t the first time the magazine had angered those in power, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last.

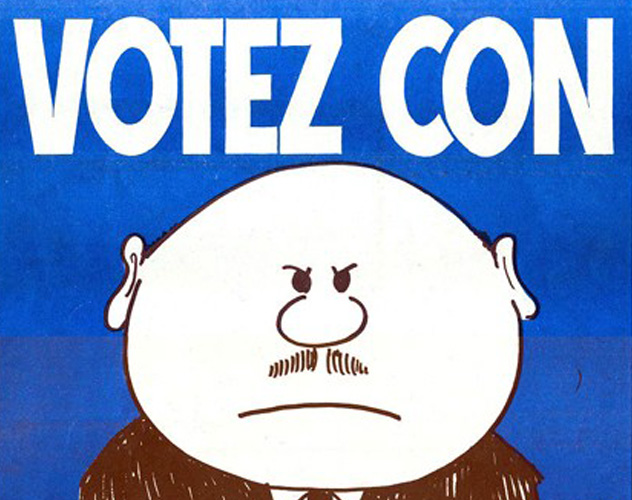

9Vote Asshole

When Hara-Kiri closed its doors for the last time, many thought they’d seen the end of the offensive weekly. No such luck. Instead of disbanding, the journalists and cartoonists took advantage of a loophole in French law and simply renamed the magazine. Charlie Hebdo (“Charlie Weekly”) had more or less the exact same staff as Hara-Kiri, the same layout, and the same mission—only with the added dig of a name that now referenced their biggest controversy. It wasn’t long before a new controversy took the place of the de Gaulle fiasco. When the French municipal elections rolled round in 1971, there was plenty of anti-government feeling in the air. The newly relaunched Charlie Hebdo took advantage of this with a cover reading “Votez Con” (“Vote Asshole”). Underneath, the paper’s cartoonists added the words “You Don’t Have A Choice.” It was a statement that resonated with a lot of disaffected people. Even today, French graffiti artists sometimes tag their works with it. It may not have matched the de Gaulle controversy, but it showed that the magazine wasn’t going to give up its “dumb and nasty” tagline anytime soon.

8Reprinting Denmark’s Muhammad Cartoons

You probably don’t recognize the name Jyllands-Posten, but you may remember their most famous issue. In 2005, the Danish paper ran a series of Muhammad cartoons, including one of the prophet with a bomb in his turban. The reaction was immediate and visceral. Riots broke out. The Danish flag was burned. Things only got crazier when the Charlie Hebdo team decided to reprint the cartoons in solidarity. It wasn’t the only magazine to take this route. In Jordan, a weekly newspaper also ran the cartoons with the caption “Be Reasonable.” But for one reason or another, it was Charlie Hebdo that got all the press attention. The Great Mosque of Paris (which has condemned the recent attack) and the Union of Islamic Organisations of France sued the magazine, and the case was brought to court. It was stated that the cartoons could incite racial violence in France, a charge with some seriously heavy penalties. It didn’t help that, around the time the trial was going on, 50 Muslim graves were desecrated with pig’s blood and swastikas. Ultimately, Charlie Hebdo and its team were acquitted under French freedom of expression laws. It was the first time that most of the world had heard about them, but it wouldn’t be the last.

7The Anti-Semitic Column

Now might be a good time to remember that Charlie Hebdo was never just about goading Muslims. The editors saw themselves as equal opportunity offenders, especially where Jews and Catholics were concerned. One famous cartoon featured a Jewish Israeli machine-gunning a Palestinian while exclaiming, “Take that, Goliath!” But while the intent was always satirical, it occasionally led to the magazine being accused of anti-Semitism. Those accusations weren’t always unfounded. In 2008, the magazine published a column by industry veteran Sine. In it, Sine claimed that then-president Nicolas Sarkozy’s son was converting to Judaism so he could get more money, something that managed to be both offensive and utterly inaccurate. The outcry that followed only got worse when it was discovered that Sine had once said, “I’m an antisemite, and I’m not afraid to admit it . . . I want every Jew to live in fear, unless he’s pro-Palestinian. Let them die.” The magazine ultimately fired Sine, claiming that it had gotten used to publishing his columns without reading them. But the controversy never truly faded.

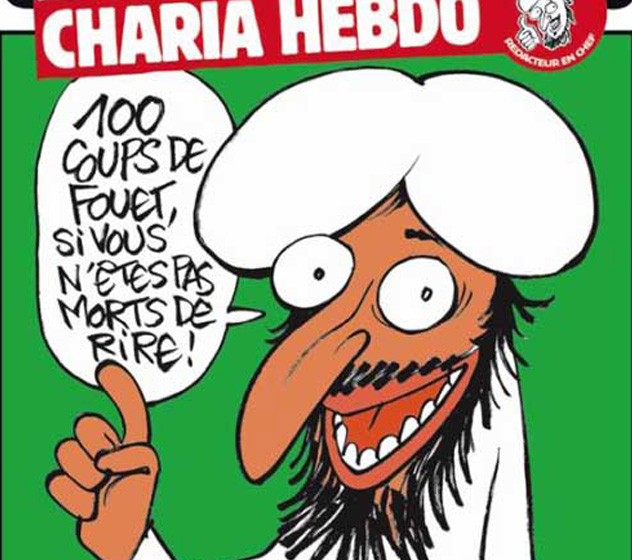

6Hiring Muhammad As Editor

Prior to the shooting, Charlie Hebdo’s most infamous moment was in 2011. To celebrate the victory of an Islamist party in the Tunisian elections, the magazine produced its “Sharia” issue—supposedly guest-edited by Muhammad. Unsurprisingly, it was incredibly offensive. The cover featured the prophet with a speech bubble saying, “100 lashes if you don’t die laughing!” But it was what happened in the hours before the issue hit the newsstands that stuck in most people’s minds. At 1:00 A.M. that morning, the offices of Charlie Hebdo were firebombed and burned to the ground. Equipment, drawings, and personal possessions all went up in flames. Simultaneously, hackers defaced the website and sent terrifying death messages to the editorial team. Although no one was killed, the attack still contained a dark message for French society: Back down or worse will come. At the time, many thought it might be the end of Charlie Hebdo. Instead, they simply increased their provocation.

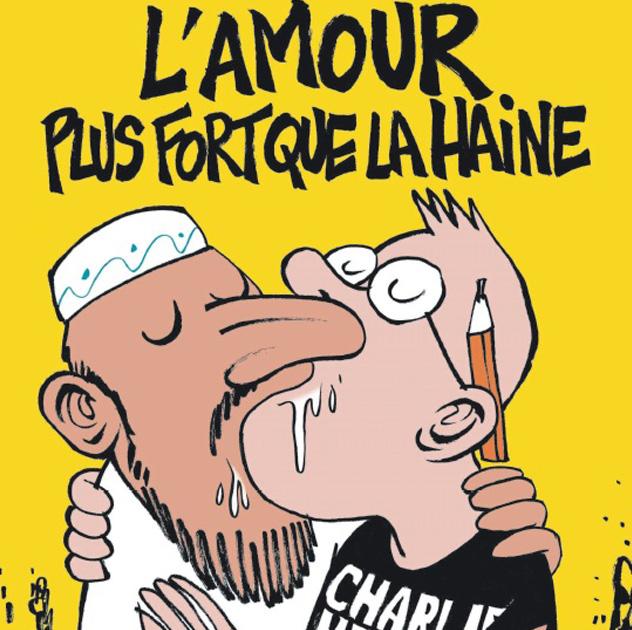

5Responding To The Firebomb

Charlie Hebdo’s response to the firebombing was designed to push buttons, and boy did it work. Within a week of the offices being torched, the magazine was back on the shelves, sporting one of its most famous covers of all. Set outside the ruined remains of its former offices, the image (shown above) depicted a male Charlie Hebdo cartoonist and a Muslim man sharing a passionate kiss. The caption simply read “Love Is Stronger Than Hate.” Even for a magazine that routinely published images of Muhammad and Israelis murdering Palestinians, this was provocative. The paper followed it up with a furious press offensive. Editor Stephane Charbonnier (better known as “Charb”) openly attacked the “idiot extremists” responsible, saying that it was his job to make their lives as difficult “as they do ours.” Not long after, he would also add his famous quote, now much more relevant following Wednesday’s attacks: “I don’t feel as though I’m killing someone with a pen. I’m not putting lives at risk. When activists need a pretext to justify their violence, they always find it.”

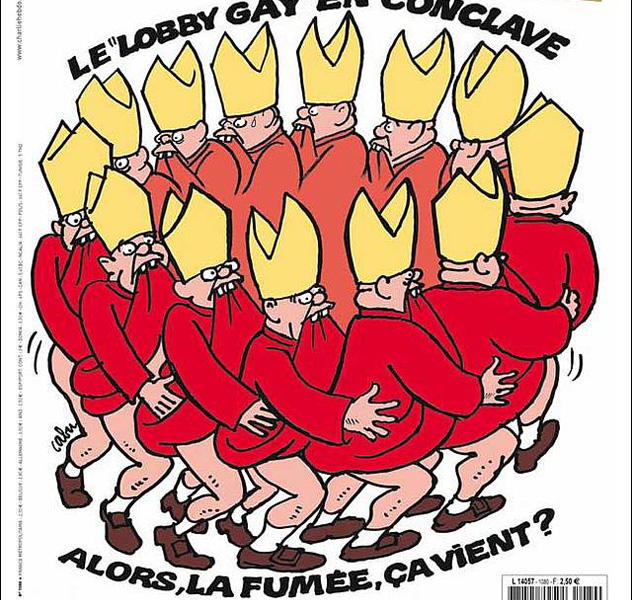

4The Catholic Covers

Along with Judaism and Islam, Charlie Hebdo had a strong dislike of Catholicism. Perhaps that’s putting it too mildly. By all accounts, the editors had it in for the Pope almost as much as they had it in for Muhammad. At the height of the Church abuse scandal, they ran a cover depicting Pope Benedict XVI as a green-skinned corpse advising his bishops on how to get away with pedophilia. The summer after Pope Francis took over Benedict’s old job, a cover cartoon showed him dressed up as a flabby drag queen at Rio’s Mardi Gras. Another showed a group of bishops sodomizing one another. Stuff like this is important because it shows how Charlie Hebdo touched a nerve with every single group on Earth. As we’ve been writing this, the Catholic League has released a statement saying that Charb “provoked” the massacre and his own death with his “disgusting” cartoons of religious figures. Although the group has condemned the killings, they’ve also added a depressing disclaimer: “Had [Charbonnier] not been so narcissistic, he may [sic] still be alive.”

3The Gay Marriage Issue

Even at their most offensive, Charlie Hebdo never just published cartoons for the sake of upsetting people. The magazine came from a strongly left-wing, feminist, and staunchly liberal background. One of its strongest principles was equal rights. So when France’s right-wing Catholics organized huge protests against the legalization of gay marriage, the magazine responded in kind. Published in November 2012, the cover of their “Mariage Homo” issue featured Jesus and God sodomizing one another while the Holy Spirit, to coin a euphemism, brought up the rear. It also made reference to outspoken gay marriage opponent Cardinal Vingt-Trois by including a caption that read “Cardinal Vingt-Trois has three fathers.” The reaction in France was nothing short of apocalyptic. Catholics and Christians of all stripes got up in arms, and gay marriage opponents were deeply offended. Although gay marriage was ultimately legalized, the cover still caused a lasting controversy.

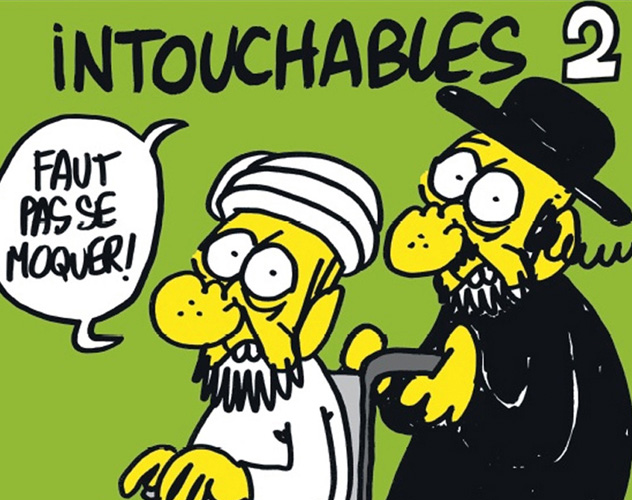

2The ‘Intouchables 2’

In 2012, one of France’s top box-office hits was a film called Intouchables. The story of a poor black man who becomes caretaker to a paralyzed rich white man, it was an utter schmaltz fest with less subtlety than a sledgehammer. However, it did inspire one of Charlie Hebdo’s more controversial covers. Featuring a Jewish caricature pushing a Muslim in a wheelchair and the caption “You Shouldn’t Make Fun Of Us,” the cartoon was designed to cause a reaction. The inside of the issue was even more provocative. Riffing on the recent release of Innocence of Muslims, it featured a filmmaker shooting scenes of a naked Muhammad in pornographic poses. The paper claimed that these scenes were sure to “set the Muslim world ablaze.” And they did. The day before the issue hit the shelves, France was forced to close 20 foreign outposts amid concerns that French nationals might be assaulted. Half the world condemned the cartoons. The Parisian press duked it out over Charlie Hebdo’s irresponsibility and right to free speech, and the magazine was given a permanent police guard. Sadly, it wouldn’t be enough to stop what happened next.

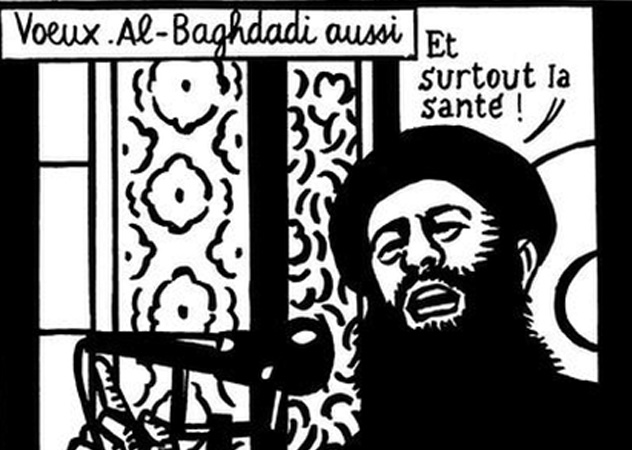

1The Last Tweet

It’s fitting that Charlie Hebdo’s last tweet before the attack would be provocative. But this one was more than simply challenging—it was a genuine puzzle, a mystery that, at the time of this writing, still hasn’t been solved. It featured a relatively lifelike picture of Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, drawn by one of the cartoonists who died in the attack, along with the caption “Best wishes. To you too, Al-Baghdadi.” Al-Baghdadi is depicted replying, “And especially good health!” Aside from having no obvious meaning, the tweet is also notable for its timing. It seems to have appeared seconds before the attack took place, with some suggesting that it may have been sent once the gunmen had already opened fire. The BBC has even entertained the possibility that the account was hacked, perhaps to send a message. Whatever the truth turns out to be, it won’t be Charlie Hebdo’s last incendiary moment. Already the magazine is planning a defiant print run of one million copies next week, while papers and websites across the globe are reprinting the images they were killed for drawing. Nine of its journalists may well be dead, but its work—offensive as it sometimes is—will carry on. Because right now, whether we agree with them or not, we are all Charlie.