Also known as the Diamond-Water Paradox, the paradox of value is the contradiction that while water is more useful, in terms of survival, than diamonds, diamonds get a higher market price. The argument could be made that diamonds are more rare than water, thus, demand is higher than supply, which means that price will go up. However, consider the fact that less than 1% of the earth’s water is drinkable. Also consider the fact that access to clean drinking water is one of the world’s most pressing problems, every year 2 million people die and half a billion become sick from a lack of drinkable water. This paradox can possibly be explained by the Subjective Theory of Value, which says that worth is based on the wants and needs of a society, as opposed to value being inherent to an object. In developed countries, drinkable water in not only abundant, it’s considered a right. Because we do not have to worry about paying for water, this gives us money to pay for things like diamonds, that do not fall out of our faucets. Individuals in developing countries surely place a higher value on clean water.

This proposal was named after economists Daniel Khazzoom and Leonard Brookes, who argued that increased energy efficiency, paradoxically, tends to lead to increased energy consumption. It was found to be true in the 1990’s. So how is this possible? Wikipedia explains it very effectively: “Increased energy efficiency can increase energy consumption by three means. Firstly, increased energy efficiency makes the use of energy relatively cheaper, thus encouraging increased use. Secondly, increased energy efficiency leads to increased economic growth, which pulls up energy use in the whole economy. Thirdly, increased efficiency in any one bottleneck resource multiplies the use of all the companion technologies, products and services that were being restrained by it.”

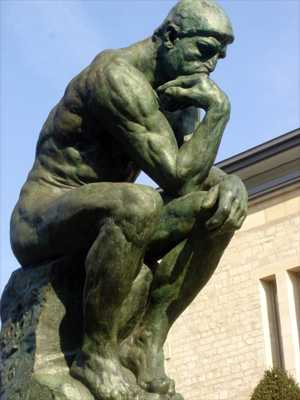

Economic theory generally assumes that individuals are completely rational, and as such, make rational decisions. Recent books on behavioral economics, notably Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational have brought forth evidence that people do not make rational decisions at all. Bounded Rationality is the idea that individual decision making is limited by personal information, cognitive limitations, and time constraints. The basic idea of economics is that people act in ways to maximize their self-interest. We do things that will increase our “utility”, or happiness. It seems logical that we would make rational decisions in order to accomplish that. Unfortunately, information asymmetry (described below), cognitive biases (read about them in my previous list) and other factors conspire to bound our rationality, and people often make choices that lead to outcomes that go against their desires.

Economics has many categories for “goods”. “Luxury Goods” are items that people buy more of as their income rises, as opposed to “Necessity Goods” like food and shelter, whose demand is unrelated to income. Examples of luxury goods include fine jewelry, expensive sports cars and designer clothing. The Lipstick Effect is the theory that during an economic calamity, people buy more less costly luxury goods. Instead of buying a fur coat, people will buy expensive lipstick. The idea is that people buy luxury goods even during economic hardships, they will just choose goods that have less of an impact on their funds. Other less expensive luxury goods besides cosmetics include expensive beer and small gadgets. Interesting Fact: After the 9/11 terrorist attacks on America, lipstick sales doubled.

The tragedy of the commons is a situation in which multiple individuals, acting independently, deplete a shared resource, even when it is not in anyone’s interest to do so. The best current example of this is fishermen. Nobody owns the earth’s fish populations, indeed, they are a shared resource. Fish are a good that people the world over consume, and as a result, there are multiple fisherman competing for these fish. Each fisherman will try to catch as many fish as possible in order to maximize his profits. However, it is also in the fishermen’s best interest to sustain the fish populations, i.e., leaving enough fish to repopulate, so that down the road, there are still fish to be caught. If each fisherman is concerned with sustainability, and they should be if they don’t want to find new careers in the near future, they theoretically will work to preserve the fish populations. Here is the problem: there is a lack of trust. A fisherman that acts responsibly and limits the amount he catches will be screwed if all the other fisherman do not. The other fisherman get more fish than he does, make more in profits, and will ultimately deplete the fish population anyway. So each fisherman, believing that the others will take more than their sustainable share, will take as many fish as he can, and the world’s fish supplies will deplete, even though no one wants them to.

The opposite of the above mentioned tragedy of the commons, the anticommons is a situation where too many owners (and bureaucratic red tape) discourages accomplishment of a socially desirable outcome. The classic example is patents. If a product requires multiple components or techniques patented by different people or companies, then it becomes difficult, time consuming and very costly to negotiate with all the owners, and the product may not be produced. This can be a huge loss if the product is in great demand or would have great social benefits. Everybody loses in this situation, the patent holders, the would-be manufacturers and the consumers who would have bought the product. Interesting fact: A single microchip contains up to 5,000 different patents. No one can create a microchip unless every single patent holder agrees to license their patent.

A perverse incentive is an incentive that has an unintended and undesirable effect which is opposite to the initial interests. A type of unintended consequences, perverse incentives are the result of an honest good intention. A historical example illustrates the problem: 19th century paleontologists traveling to China used to pay peasants for each piece of dinosaur bone that they presented. It was later found the peasants found bones and then smashed them into many pieces, which significantly reduced their scientific value, to get more payments. More modern examples include paying architects and engineers based on project costs, which leads to excessively costly projects as they overspend unnecessarily to make income.

Information asymmetry is a prevalent issue in economics. In most sales transactions, the seller has more information than the buyer, and as such has the opportunity to try to pass off low quality or defective products for higher prices. This leads to buyer distrust and the old idiom: Buyer Beware. Adverse selection is a market process where information asymmetry causes negative results. A good example is health insurance. Insurance companies depend on a mix of clients: they need a certain number of healthy individuals (low-risk) to pay premiums and not use a lot of services so that the premium prices can average out. However, the people most likely to buy health insurance are people who need it because of health problems (high-risk). These people are more costly to the insurance companies because they need more services than a healthy person. The insurance companies do not know every new policy applicants health status (but they certainly do everything in their power to find out as much as they can), and this lack of information requires the companies to raise premiums to mitigate the risk. This increase in premiums causes the healthiest people to cancel their insurance. This leads to a further increase in premium price as the insurance companies now have a riskier group, which leads to the now healthiest people canceling their insurance, continuing the “adverse selection spiral”, until the only people insured are the direly ill. At this point, the premiums paid will not even begin to offset the costs of the sick. In theory, this could lead to the collapse of the health insurance industry, however, this is an unlikely scenario as their risk is diminished by things such as employer offered insurance, which includes a large set of healthy individuals who average out the risk. Another information asymmetry example is the “Market for Lemons”, a term coined by the economist George Akerlof. The used car market is the classic example of quality uncertainty. A defective used car (“lemon”) is generally the result of untraceable actions, like the owners driving style, maintenance habits and accidents. Because the buyer does not have this information, their best assumption is that the vehicle is of average quality, and therefore will pay only an average fair price. As a result, the owner of a car in great condition (“cherry”), will not be able to get a price high enough to make selling the cherry worthwhile. End result: the owners of good cars will not sell their vehicles in the used-car market. This reduces the quality of cars in the used-car market, this reduces the price buyers will pay, this further reduces the quality of cars sold. You get the idea.

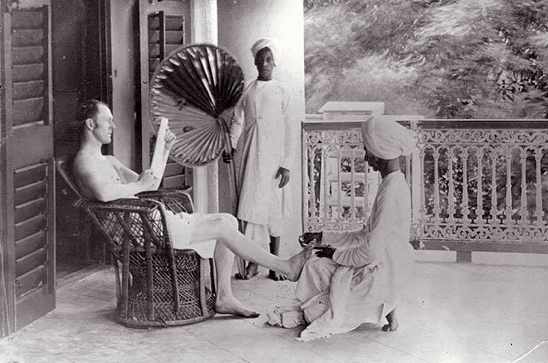

This is when the solution to a problem actually makes the problem worse. The term ‘Cobra effect’ comes from an anecdote from colonial India. The British government wanted to decrease the population of venomous cobra snakes, so they offered a reward for every dead snake. However, the Indians began to breed cobras for the income. When the government realized what was going on, the reward was canceled, and the breeders set the snakes free. The snakes consequently multiplied, and increased the cobra population. The term is now used to illustrate the origins of wrong stimulation in politics and economic policy. Unfortunately, some of the crises facing our world are the result of honest attempts to solve problems.

This is the idea that giving charity reduces an individual’s incentive to help themselves. When given assistance, the recipient has two choices: use the aid to improve their situation, or come to rely on the aid to survive. Obviously, good Samaritans give assistance in the hopes of the former, that the recipient will use the aid to improve their situation. For example, when a country gives financial aid to another country who has experienced a natural disaster, we assume that the money will go to helping the victims, cleaning, rebuilding, etc. Arguers against charity often bring up this dilemma, claiming that beneficiaries of such aid lose incentive to work or become productive members of society. This can be seen in action when people who want to give a dollar or two to a homeless person do not, because they are afraid the person will buy booze with it. A “transfer of wealth” of a couple of dollars from someone who can spare the dollars to someone who will use the dollars to improve their situation is a wonderful arrangement. However, if the recipient of the dollars is not going to use the money for a noble purpose, and instead is going to buy illicit drugs with them, it is a less desirable arrangement, and most charitable people would decline to give the dollars. Here’s the problem: it is hard to know how the person you are giving the dollars to will use the funds, so people might instead opt to not give to any homeless people. Now the individuals who would have used the money to improve their situations suffer.