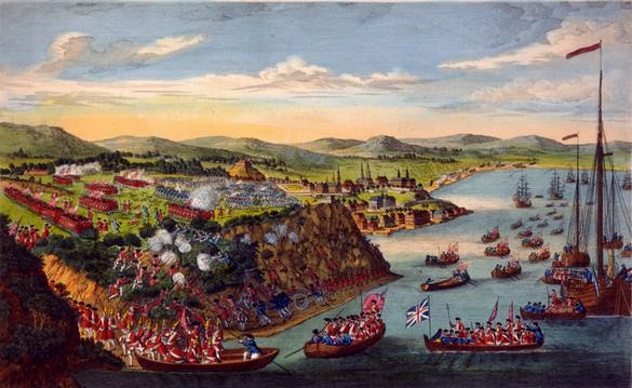

10 French And Indian War

Before and during the American Revolutionary War, not many maps of the American continent existed. Consequently, many military maps were made in the field, often under fire, and battles might be won or lost based on their accuracy. According to authors Richard Brown and Paul Cohen, maps sometimes even caused war. Countries involved in land disputes have backed up their claims to the disputed land with maps that didn’t clearly represent the owner of the land in question. One such map, by John Mitchell, was a contributing cause to the French and Indian War, according to Brown, “because it showed claims of the British possessions, which was one of its purposes in the first place.” Maps made by British officers on-scene corrected misconceptions about topography and the navigability of waterways. In 1759, during the French and Indian War, Captain James Cook needed to move General James Wolfe’s troops 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi) down the St. Lawrence River, from Louisburg, Nova Scotia, to Quebec, but the river was considered “unnavigable.” At night, Cook mapped the river, allowing the British ships to traverse an area the French thought to be impassible. As a result, Wolfe captured the city of Quebec.[1]

9 Napoleon’s Defeat At Waterloo

Napoleon Bonaparte lost the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, in part because of a map error. According to documentarian Franck Ferrand, Napoleon aimed his artillery in the wrong direction, far short of the British, Dutch, and Prussian lines. Napoleon relied on an inaccurate map when planning his strategy for the battle, which explains why he didn’t know the lay of the land and became disoriented on the battlefield. According to Ferrand, “It is certainly one of the factors that led to his defeat.” Due to a printing error, the map showed a strategic site, the Mont-Saint-Jean farm, 1 kilometer (0.6 mi) from its true position, which was the range of Napoleon’s misdirected guns. It also showed a nonexistent bend in a road, according to Belgian illustrator and historian Bernard Coppens, who found the bloodstained map at a Brussels military museum.[2]

8 Fatal Bombing Mishap

In July 2006, the Israeli military duplicated a map for a bombing run against a target in Southern Lebanon. An error on the copy of the map identified a United Nations post as a Hezbollah position. As a result, four international observers were killed. Israeli officials expressed their “deepest condolences and sincere regret.” Mark Regev, Israel’s foreign ministry spokesman, acknowledged that “a mishap on the Israeli side” during the copying of the maps resulted in the failure to correctly identify the UN post’s position, leading to the calamity. The observers, who were from China, Austria, Finland, and Canada, were killed by a precision-guided bomb on July 26. The Hezbollah positions were 180 meters (590 ft) from the UN building.[3]

7 Nicaraguan Invasion

In November 2010, Nicaraguan troops led by former Sandinista guerrilla commander Eden Pastora crossed the San Juan River near the Caribbean coast. Invading Costa Rica, their neighbor to the south, the soldiers planted their country’s flag in the soil of Costa Rica’s Calero Island, which is located in an area claimed by both nations. Google Maps almost decided the issue by placing Calero Island inside Nicaragua’s border. “See the satellite photo on Google, and there you see the border,” Pastora said. Costa Rica has no army, but it sent security forces to support the 150 agents already in the area.[4] The dispute was solved judicially, rather than militarily, when the United Nations’ International Court of Justice ruled that the island, which measures 3 square kilometers (1.2 mi2), and its wetlands should be ceded to Costa Rica, since it has sovereignty over the area. The court also took Nicaragua to task “for violating Costa Rica’s right to navigation in the waters” along the countries’ joint border. Although the international court is powerless to enforce its judgments, both countries must agree to its ruling before their case will be heard by the tribunal. Nicaragua’s deputy foreign minister Cesar Vega said Nicaragua would “abide by the verdict.”

6 Grounded Minesweeper

According to the United States Navy, its minesweeper USS Guardian ran aground on a Philippines reef because of an error on a navigational chart. The ship’s January 16, 2013, collision damaged the Tubbataha Reef, which is located in a protected area and is home to “one of the most biologically diverse areas in the Coral Triangle.” The Philippines government demanded an investigation of the incident to determine whether the US violated Philippines or international laws.[5] It was ultimately found that the US Navy damaged 2,345 square meters (25,241 ft2) of the coral reef, and the US paid $2 million in compensation and helped the Philippine Coast Guard to upgrade its station at Tubbataha. The Philippines said that the money will help to rehabilitate and protect the reef as well as enhance monitoring of the area to prevent any similar incidents from occurring. The Guardian‘s captain and other officers were faulted for the incident because they failed to adhere to standard navigation procedures when the minesweeper ran aground.

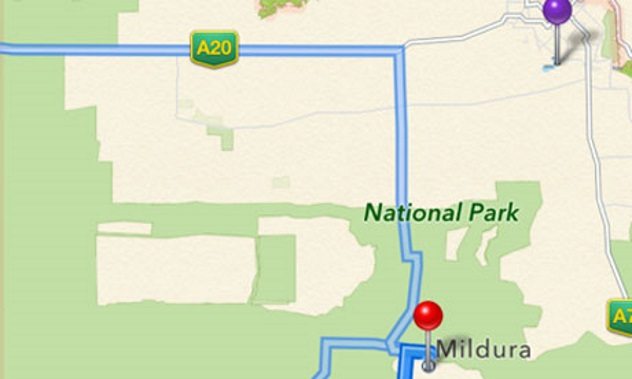

5 Stranded Drivers

Following Apple Maps directions, Australian motorists found themselves stranded in remote Murray-Sunset National Park. The drivers’ destination was Mildura, 72 kilometers (45 mi) away. In December 2012, police issued a warning to travelers not to rely on the application. Using the app, they cautioned, could be “life-threatening.” The official Australian Gazetteer shared responsibility for the map error, because its list of place names and coordinates, which Apple Maps uses as a reference, has two Milduras. The first is the actual town (purple pin above), and the second is a point located in the middle of the remote national park (red pin). Apple Maps understood the latter to be the former, and the app’s directions were based on this misunderstanding. Apple’s CEO Tim Cook admitted to the mistake and promised to correct it.[6]

4 International Territory Claim

For more than a century, Canada’s official maps have erroneously included part of the North Pole area as its own territory. The claim conflicts with international law, which states that nations with territory near the Arctic Circle can only claim 370 kilometers (200 nautical miles) of ocean off their northern coasts as their own waters. Anything beyond that distance is legally international waters. Canada’s claim arose from the old-fashioned “sector theory,” in which the Arctic Ocean was divided into triangular slices, with the pole as their meeting point in the center. The theory was never accepted as Canada’s official position on the matter. The old maps’ mistake increases the territory of Canada by 200,000 square kilometers (77,000 mi2), almost all of which is ocean. This additional area is roughly the size of the UK or all five Great Lakes. In December 2013, perhaps inspired by the sector maps’ mistake, Canadian officials decided to submit a claim of sovereignty over the entire North Pole and its wealth of natural resources, including oil. The claim would enlarge Canada’s territory by 1.2 million square kilometers (463,00 mi2), or about the size of Alberta and Saskatchewan combined. A subsequent claim would expand its territory even further. Before the claim can be submitted, however, Canada must map the area. Even if the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf agrees with Canada’s claim, its decision is nonbinding and would merely open negotiations between countries with their own territorial claims in the Arctic. Such disputes could take years to resolve.[7]

3 Wildlife Endangerment

Mapping mistakes that have persisted from the late 20th century into the 21st century continue to endanger African wildlife in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Luama Katanga Reserve. As a result of the errors, the reserve’s boundaries were shifted 50 kilometers (31 mi) to the west. Now, plants and animals that should be protected could be at risk, as mining, agricultural, cattle grazing, and forest clearing operations move in. “The moral of this story is that keeping track of parks—and especially getting maps and boundaries correct—matters hugely for biodiversity,” said James Deutsch, WCS Vice President of Conservation Strategy. A newly documented species of vegetation, Dorstenia luamensis, a hanging, fern-like plant, is among the flora in the 230,000-hectare reserve, which is also home to 1,400 chimpanzees, whose lives would be threatened should the clearing of forests destroy their habitat. Deutsch urged that the maps be corrected and the reserve protected.[8]

2 Flood Insurance Refusal

One of the responsibilities of the US Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) Flood Map Service Center is to serve as the “official public source for flood hazard information produced in support of the National Flood Insurance Program.” Its flood maps are important for three reasons: First, they’re intended to save lives by assessing an area’s flood risk and recommending relocation if need be. Second, they assist communities with managing their flood plans. Third, they’re used by insurance companies to determine homeowners’ flood insurance rates. The mission and the objectives of FEMA’s flood protection program appear to be in jeopardy in some cases, due to map mistakes. These errors have created a dilemma for the city of Rochester, Massachusetts. Despite the new FEMA flood plain maps’ numerous errors, Rochester must adopt them to be eligible for federal flood insurance assistance. If the city refuses to accept the mistaken maps, many homeowners could end up losing their insurance. FEMA’s latest maps of the area are based on older, erroneous maps, to which the new maps add mistakes of their own. Conservation agent Laurell Farinon said that some of the maps’ data make no sense. Rochester Planning Board member Ben Bailey agreed that the maps are “fundamentally flawed.” One of their errors affects him personally: “The line that goes through my property goes up a 20-foot hill and back down again. You don’t have to be an engineer to see that this is inaccurate.” As a result of the error, his insurance company refused to offer him homeowner’s insurance. Massachusetts forbids insurance companies to raise their rates, so Bailey couldn’t get insurance by paying more. The appeals period has ended, so homeowners are left with two options: Do without insurance or pay engineers to reevaluate their property. And it’s not only homeowners who suffer from FEMA’s map errors. The maps are also used by the Planning Board, the Conservation Commission, and building inspectors. FEMA assumes their maps are correct, placing the burden of proving them wrong on the landowners.[9]

1 Demolition Of House

It wasn’t their fault they tore down the wrong house, a demolition team argued in 2016. The blame lay with Google Maps. The house numbers were identical, but the duplexes were located on different streets. To explain the mistake, an employee of the demolition firm e-mailed a homeowner a copy of a Google Maps photo showing an arrow pointing to the demolished house she owned with another person. The map’s arrow pointed at the duplex on 7601 Calypso Drive, Rowlett, Texas—but identified its address as 7601 Cousteau Drive. The firm was supposed to demolish the duplex on Cousteau.[10] Despite the company’s contention that Google is at fault, Gerry Beyer, a law professor at Texas Tech University, is doubtful. “My gut reaction is that Google would not be liable,” he said, because Google’s terms of service clearly state that users are responsible for the actions they take based on Google Maps.