10 Frankenstein; Or, The Modern PrometheusMary Shelley

Nearly two centuries after its publication, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus continues to fascinate readers. Not only has the novel become a landmark of both the sci-fi and Gothic horror genres, it also established its author as one of the few outstanding female novelists prior to the 20th century. But what if Mary Shelley wasn’t the true author of Frankenstein? As incredible as it might sound, that’s the claim advanced by author John Lauritsen in his book The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein. Lauritsen argues that the famous novel was actually penned by none other than Mary Shelley’s husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Lauritsen’s case is superficially compelling, despite his flawed credibility. (He has no training as a literary historian and denies a causal link between HIV and AIDS.) He argues that Shelley, a teenager with little education, could not have mustered the literary sophistication and lyrical brilliance on display in Frankenstein. Lauritsen also says the novel is pervaded with themes of male homoeroticism, a subject supposedly more in keeping with Percy Shelley’s psychology than his wife’s. According to Lauritsen, the truth of Frankenstein‘s authorship has been suppressed by feminists in the academic establishment. Some will no doubt detect misogyny in Lauritsen’s charge. However, the debate took an interesting twist thanks to feminist author Germaine Greer. In her review of The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein, Greer argues that Shelley really was the author of Frankenstein. But Greer insists this is nothing to brag about. After all, in her estimation, Frankenstein is badly written.

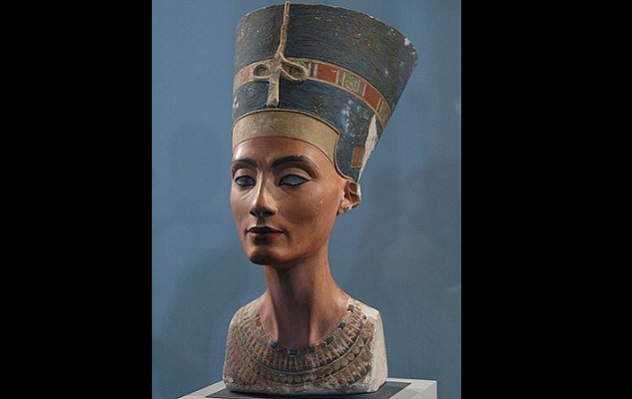

9 The Bust Of Nefertiti

“Suddenly we had in our hands the most alive Egyptian artwork. You cannot describe it with words. You must see it.” So wrote the archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt in his diary shortly after his team unearthed the famous bust of Nefertiti. Borchardt was right. The bust—said to depict the wife of Akhenaten, Egypt’s Sun King—is indeed a revelation. With its strikingly vivid colors and anatomical fidelity, the work manages to convey an aura of majesty that contrasts with its sheer delicacy. It’s almost unbelievable that such an exquisite masterpiece could have survived through the centuries. Of course, if we listen to Swiss art historian Henri Stierlin, it is unbelievable. According to Stierlin, the bust’s false reputation began with a duped aristocratic. Sometime in 1912, the story goes, Borchardt commissioned an artist to create a decorative piece on which to display an ancient necklace. Wanting to experiment with ancient materials, Borchardt ordered the bust to be painted with pigments from his archaeological archives. (Hence the reason why it has been able to pass forensic tests.) However, when the bust was seen by the the Prussian prince, Johann Georg, he mistook it for a real artifact. Prince Georg was reportedly so enamored with the work that Borchardt lacked the nerve to tell him the truth. It wasn’t long before the deception took on a life of its own, and today, the world reveres the bust of Nefertiti as a 3,000-year-old treasure . . . when really it’s a 100-year-old fake. (The bust currently resides in the Berlin Museum). Stierlin’s account remains a minority position. Still, doubters are unlikely to be quieted any time soon. As Stefan Simon, a scientist who specializes in authenticating ancient works, has admitted, “You can prove a fake, but you can’t prove originals.”

8 FlowersPaolo Porpora

If you ever drop by Taipei, Taiwan, you might spot a painting entitled Flowers, a still life touted as the work of the 17th-century painter Paolo Porpora. However, an Italian auction house confirmed that the same painting had been listed in their catalog, and that it’s actually the work of a lesser artist named Mario Nuzzi. Now, fakes and misattributions aren’t all that rare in the art world. But what makes the case of the (possibly) misidentified Porpora noteworthy is the manner in which the alleged mistake was discovered. In August 2015, surveillance cameras captured a 12-year-old boy punching a hole through the painting after seemingly losing his footing. The video went viral, prompting the aforementioned Italian auction house to reach out to the media, letting the world know of the error. And what an error it was. The painting the boy had damaged was reported to be a masterpiece worth $1.5 million, yet the Nuzzi work was valued at considerably less—roughly around $30,000. The organizers of the Taipei exhibition continue to insist that their Flowers is indeed an authentic Porpora, though they’ve yet to provide any proof. But the story gets even more bizarre. Apparently, museum oversight in Taiwan is quite lax, and it may be that the entire Taipei exhibition is itself a sort of counterfeit operation. For one thing, the exhibition is not actually associated with a museum. Instead, it exists in a rented-out venue. It also doesn’t provide the climate controls—or the security—needed to preserve the priceless works that are supposedly inside. Should you be in Taipei and want to visit, the exhibition is called “The Face of Leonardo, Images of a Genius.” But be warned that the self-portrait of Leonardo on display is also of dubious authenticity.

7 La Bella PrincipessaLeonardo Da Vinci

The portrait known as La Bella Principessa (The Beautiful Princess) was sold at auction in 1998. While it was originally thought to be a 19th-century German work, some suspected it was much older. Many also thought its exquisite rendering must surely be the work of an extraordinarily gifted artist. The owner agreed to have it analyzed, and when the verdict was returned, the art world was absolutely astonished. La Bella Principessa was by none other than Leonardo Da Vinci. In order to confirm the work as a Leonardo, a team of experts, headed by Oxford Renaissance scholar Martin Kemp, subjected the portrait to a painstaking battery of tests. Every little detail was rigorously analyzed. The team even paid attention to the direction of the brushstrokes. Just one right-handed stroke was enough to cast doubt on Leonardo’s authorship, as the Renaissance painter was left-handed. But after Kemp finished his analysis, an impressive list of authorities accepted his attribution. However, a choir of incorrigible skeptics remains. Not only do some say the work lacks the spirit of the great master, they also point to several suspicious details. For example, the drawing is rendered on vellum, a material Leonardo was unknown to use. Also, in November 2015, convicted art forger Shaun Greenhalgh claimed the piece as his own handiwork, saying he modeled the work after a girl who worked at a supermarket he once frequented. The painting’s current owner, Peter Silverman, balks at Greenhalgh’s claim. Silverman has challenged Greenhalgh to reproduce La Bella Principessa in front of a committee of experts, with a prize of £10,000 (about $15,000) if he succeeds. And if he fails, Silverman says, “He goes back to jail where he belongs.”

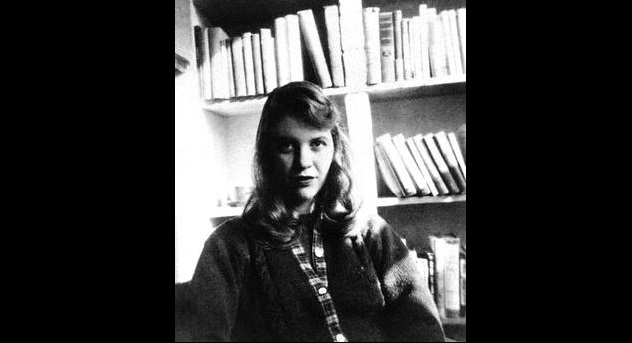

6 Ariel And Other PoemsSylvia Plath

In 1963, Sylvia Plath was a 31-year-old poet of modest reputation. Recently estranged from her husband, the poet Ted Hughes, Plath was spending the winter in London, looking after the couple’s two young children. Sadly, on the morning of February 11, Plath gassed herself to death in her townhouse oven. Upon her death, Plath left behind a completed volume of poetry that, owing both to her sensational biography and to the sheer brilliance of her craft, would soon be hailed as a literary masterpiece. This book was titled Ariel and Other Poems. Published in 1965, it remains one of the 20th century’s most celebrated books of poetry. However, many Plath admirers have insisted that the Ariel we know is not the original work. While Plath and Hughes were separated at the time of her death, Hughes remained her literary executor, able to wield complete editorial control over her posthumous works. Hughes admitted to rearranging Plath’s chosen order for the Ariel poems. He also omitted works he deemed too “personally aggressive,” by which he meant angry poems that were addressed at him. Hughes died in 1998, and in 2004, the couple’s daughter collaborated in the release Plath’s original manuscript, now titled Ariel: The Restored Edition. Reviewers noted that while the Hughes-edited work had emphasized Plath’s characteristic themes of despair, Plath’s own volume presented an attitude of hope. For example, Hughes chose to have his version end with “Edge,” a gorgeous yet bleak poem. However, the restored work ends with the meditative “Wintering,” which concludes with these optimistic lines: What will they taste of, the Christmas roses? The bees are flying. They taste the spring.

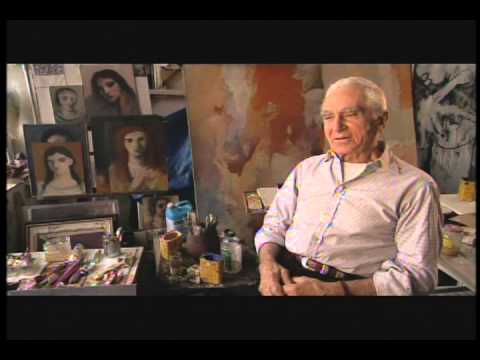

5 Teri Horton’s Jackson Pollock

Teri Horton was a 73-year-old former truck driver who purchased a painting for five dollars from a local thrift shop. The piece was intended as a gift for a friend. However, when it proved too large for the friend’s trailer, Horton decided to sell it at a yard sale. That’s when a local art teacher noticed the painting bore a remarkable similarity to the work of Jackson Pollock. But could it be an actual Pollock? Many seem to think so. Forensic analysis on the painting yielded a fingerprint consistent with those found on Pollock’s authenticated works. Additionally, no less an authority than Nicolas Carone, a friend of Pollock and a famous painter in his own right, has testified to the painting’s veracity. Nevertheless, skeptics remain. Doubt has been cast on the fingerprint analysis. And some believe the work is too inferior to be attributed to Pollock, an artist who developed techniques that are difficult, if not impossible, to reproduce. But whether the work is real or not, we shouldn’t despair for Horton. She was offered $9 million for the painting by a Saudi buyer. She refused the offer, however, saying she won’t accept anything less than $55 million. And if you’re interested in learning more about the disputed Pollock, the story is recounted in the film Who the #$&% is Jackson Pollock?

4 To Kill A MockingbirdHarper Lee

y Literary legends Truman Capote and Harper Lee grew up as childhood friends in Monroeville, Alabama. Perhaps it was inevitable that they would drift apart in later life, given their radical divergence in temperament. Capote was a flamboyant man-about-town and self-destructive party animal, while Lee was a shy homebody who became famous for her reclusive nature. Prior to their estrangement, however, the two were close confidantes and avid readers of each others’ work. But some have claimed their collaborations went beyond mere criticism and encouragement, and that Capote actually wrote much, if not all, of a Lee’s landmark novel, To Kill a Mockingbird. The rumor was apparently started by Pearle Belle, an editor from Cambridge, Massachusetts, who allegedly claimed that Capote confided his secret to her. Capote’s father, Archulus Persons, also said that Lee merely provided the outline for the novel, and that “it was his genius son that made the novel sing.” The rumor seemed to have been put to rest when a letter from Capote to Lee emerged in 2013. In the note, Capote congratulates Lee on the novel but gives no indication of a prior collaboration. Yet perhaps such written proof was unnecessary. The historian Wayne Flynt once summed up what may be the strongest case against Capote’s authorship. Flynt points out that Capote was well-known for his “enormous ego” and habitual “self-promotion.” Or in other words, “To assume, as jealous as [Capote] was of Harper Lee’s success, that he would not have claimed credit for [Mockingbird] if in fact he had done it, is simply too much . . . to believe.”

3 The Madonna Of The PinksRaphael

For generations, it was standard practice for art apprentices to hone their craft by imitating the works of the masters. And in an era before mass photographic reproduction, those copies were both highly prized and widely circulated. So would it come as a surprise if, after centuries, one of those copies should be mistakenly accepted as an original? Well, that was thought to be the fate of The Madonna of the Pinks, a painting by the Renaissance master Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael. For years, one painting in particular was reputed to be Raphael’s Madonna of the Pinks. No bigger than a standard-sized sheet of paper, the work depicts the Madonna and Child, each holding up a pair of carnations. (The flowers, the “pinks” of the paintings title, symbolize marital love, and thus the Virgin Mary’s role as the Bride of Christ.) In 1860, however, Raphael scholar Johann David Passavant denounced the work as a copy. For decades, his judgment was taken as authoritative. It wasn’t until 1991 that a gallery curator named Nicholas Penny gave the painting another close look. Intrigued by the smallest anomaly in the painting’s background, Penny arranged to have the work examined using modern forensic technology. The new techniques revealed, among other things, the painting’s underdrawing, which indeed proved to be characteristic of Raphael. Other clues also pointed to the master’s authorship, and the work has since been restored to its former glory. The painting is now widely accepted as the true Raphael, and it currently resides in London’s National Gallery. However, the acerbic critic Brian Sewell was one formidable authority who remained skeptical of the little oil painting. Sewell dismissed the attribution based on the quality of the painting, as well as the chronology of Raphael’s life. (The painting was said to have been an early Raphael, done in 1506–1507, which Sewell thought unlikely.) Sewell also provided an explanation for why “rediscovered” masterpieces receive such feverish welcome. According to the critic, “There are a lot of people who want to be fooled. There are a lot of people who want to discover another Rembrandt drawing. If you discover a genuine Rembrandt . . . you become associated with it. It makes you important, because it is important.”

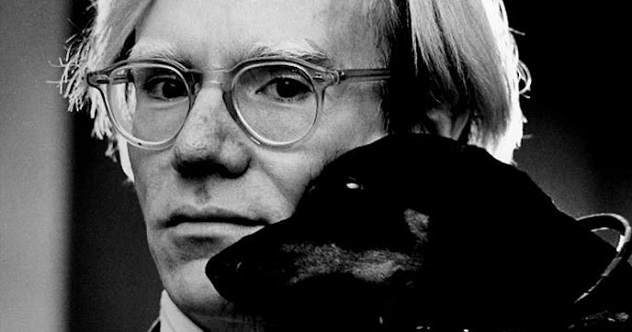

2 The ‘Bruno B’ Red Self-PortraitAndy Warhol

The painting known as the “Bruno B” is a portrait of Andy Warhol, produced with one of the artist’s own silk screen plates. Warhol himself signed and dedicated the painting to his friend, the art dealer Bruno Bischofberger (hence the “Bruno B” designation). What’s more, Warhol so admired the piece that he personally chose it to appear on the cover of the first major monograph of his work, published in 1970. Despite those impressive markers of authenticity, however, “Bruno B” is not considered an original Andy Warhol—at least not by the Andy Warhol Authentication Board, Inc., the organization charged with authenticating works by the infamous artist. When the painting’s current owner submitted to it the board for authentication, they returned it stamped with the word “DENIED.” So what was the board’s reasoning? The work couldn’t qualify as a true Warhol, since the artist himself was not actually present at its creation. As it turns out, “Bruno B” was silk screened by an independent printing firm, which had been given permission by Warhol to use his plates. There’s only one problem with this rationale. Warhol rarely created his own pieces. At the height of his career, Warhol often involved himself only with the conceptual stage of his works. The actual execution would be left to assistants at his art studio (which, because of Warhol’s assembly line methods, was known as “The Factory”). Oftentimes, Warhol’s only physical interaction with one of his paintings came when he signed it. In fact, Sam Green, curator of Warhol’s retrospective at Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art, attests that Warhol admired “Bruno B” precisely because it “exemplified his new technique for having works produced without his personal touch.” All things considered, it does appear that the denial of the authenticity of “Bruno B” is an instance of overreach by members of the artist’s foundation, none of whom, ironically, were actually appointed by Warhol himself.

1 The Polish RiderRembrandt

In 1639, the Dutch master Rembrandt purchased an enormous house in a fashionable district of Amsterdam. He was, by that time, a world famous painter, yet the house proved more than he could afford. He would go bankrupt in 1656. In the meantime, however, Rembrandt was able to to finance his purchase by taking on a bevy of students. The result was surely a boon for the art world in Amsterdam, though it would cause endless headaches for later generations of scholars. As it turns out, Rembrandt’s school was so extensive and its students so accomplished that experts often have trouble sorting out true Rembrandts from the works of his talented disciples. In order to remedy that situation, the Rembrandt Research Project (RRP) was launched in 1968 with the goal of authenticating every Rembrandt in existence. The result was a wild fluctuation in fortunes. As The Wall Street Journal reported, the number of “authentic” Rembrandts plummeted from over 700 in the 1920s to just under 300 by the 1980s. Of course, given the stakes involved, it should come as no surprise that debates still rage on, and the RRP itself has been known to reverse its findings. All this finally brings us to the The Polish Rider. Now hanging in New York’s Frick Collection, The Polish Rider has long been hailed as one of Rembrandt’s most excellent works. However, doubt was cast on its authenticity by a member of the RRP. Other members disagreed, and the official word now is that the painting is indeed by Rembrandt—with substantial contributions from his students. The RRP came to an end in 2011, having fallen short of putting its stamp of approval on every true Rembrandt. Yet it may be that the RRP’s mission was a fool’s errand all along. As the art critic Robert Hughes writes, “If one of [Rembrandt’s students] did a painting he liked, he was quite capable of signing it with his own name, keeping it and selling it as an autographed work by ‘Rembrandt.’ Criteria of originality and authorship were much more relaxed in the 17th century than they are now.” Ed Barreras bides his time in Long Beach, California.