10 He Didn’t Actually Inspire Dracula

While everyone considers Vlad Tepes the inspiration for Dracula, Bram Stoker’s son, Irving, claimed that his father came up with the idea in a dream. Proof has been elusive for decades, since most of Stoker’s research notes were missing until they turned up at Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum & Library in 1972. Between Stoker’s death in 1912 and the reappearance of his notes, historians developed the idea that Stoker was present at a dinner party with Henry Irving and Hungarian professor Arminius Vambery—who must have talked about Vlad Tepes. The link between Dracula and Vlad III first showed up in 1958 in the work of researcher Basil Kirtley. He pointed to Abraham Van Helsing’s biography as proof of the link, and the idea was echoed again and again before being recanted by the Stoker researchers who discovered his notes. Now that the notes have been examined, there is no evidence to suggest Vlad III had anything to do with the development of the world’s most famous vampire, but the myth persists.

9 The Use Of Vlad’s Name Might Be Accidental, Too

The only inspiration that Vlad Dracula gave to Bram Stoker’s titular vampire was his name, and even that might be a stretch. The connection between vampires, staking, beheading, and Vlad the Impaler seems like it should be a given, but nowhere in Stoker’s notes is there any indication that he was even aware of a figure named “Vlad the Impaler.” On vacation in Whitby in 1890, Stoker found a copy of a book called An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldovia. Buried in Stoker’s notes is a reference to a footnote in the book, simply saying, “DRACULA in Wallachian language means DEVIL.” It’s entirely possible that the name was chosen for this meaning, not the connection to Vlad III, who wasn’t mentioned in the notes. In fact, the original name Stoker chose for Dracula was “Wampyr.”

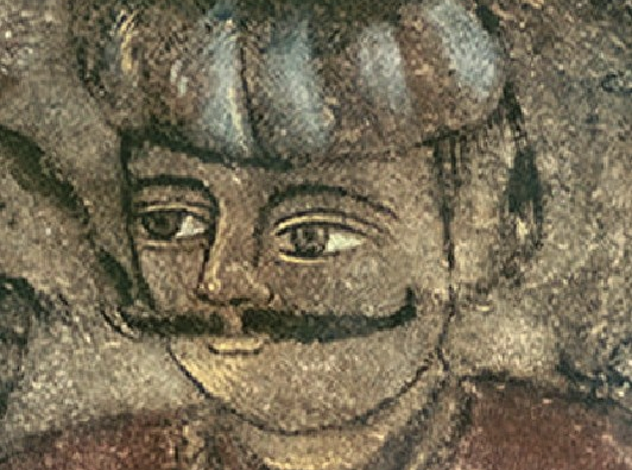

8 The Meaning And Use Of ‘Dracula’ Is Still Debated

While Stoker wrote that “Dracula” meant “devil,” there’s still a debate over what the name actually meant. “Dracula” is generally said to refer to Vlad’s father (pictured above) and to identify Vlad III as the “son of Drakul.” That, in turn, has been translated into the “son of the Dragon” or “son of the Devil,” which was linked to his dark reputation. Romanian scholar and historian Aurel Radiutiu has a different theory which starts with the idea that it was highly unlikely that a tyrannical leader would appreciate being called “the Devil.” Instead, he says that the name is actually a misspelling of the Slavic-Romanian “Dragu,” which meant “the dear one.” “Drakul” was likely a corruption of “Dragu” and came from the German-speaking Saxons that lived on the lands of Vlad II and Vlad III.

7 The Idea Of Blood Drinking Came From A Mistranslation

Vlad III’s cruelty was legendary, but the idea that he drank the blood of his enemies may have come from nothing more than a mistranslation. In 1463, a poem called “Von ainem wutrick der heis Trakle waida von der Walachaei” (“Story of a Violent Madman Called Voivode Dracula of Wallachia”) was performed for the Holy Roman emperor Frederick III. When it was translated in the 20th century, it included the idea that Vlad III dipped his bread in the blood of the men, women, and children he had impaled. But even the translation, done by scholars Radu Florescu and Raymond McNally, includes the term “basically” regarding what the poem actually says. Another look at the verse in question shows that it actually says that he washed his hands in blood. While that’s certainly still dark, it’s also entirely possible that it wasn’t literal reference but more of a metaphorical bloodbath.

6 He Probably Never Lived In Transylvania

Transylvanian tourism is all about their connection to the fictional vampire and their most notorious ruler, but some historians believe that it’s doubtful at best that Vlad III ever actually lived there. Florin Curta, a professor of archaeology and medieval history at the University of Florida, suggests that this is another case of Dracula inspiring stories about the real Vlad Tepes. He certainly never lived in Bran Castle, the most famous of Dracula’s residences. While it’s possible he was born in his father’s home in Sighisoara, it’s equally possible that he was born in Targoviste, the royal seat of Wallachia.

5 Vlad The Folk Hero

At the end of the 19th century, Vlad III was far from a hated, villainous leader. Numerous pieces of literature detailed his heroic fight for freedom from the Turks. The medieval ruler became a national hero, hailed for his military genius and crusade for national pride. While not all literature was so idealized (like those that focused more on Vlad’s methods than on his end goals), whether Vlad was a tyrant or a hero is still hotly debated. Stoker’s Dracula was banned by Nicolae Ceausescu and wasn’t released in Romania until 11 months after his execution. Now, Romania capitalizes on tourism based on a completely fictional image of their most famous ruler, who had been heralded as the one who stood up against the Turks. No one debates that 100,000 people died at Vlad’s command, so factor in the vampire mythology with a debate on whether or not the ends justify the means, and the figure of Vlad III is very convoluted indeed.

4 He Allied With Pope Pius II

After Vlad and his brother spent time as hostages of the Ottoman Empire, they had understandably strong feelings about their captors. While Radu converted and became pro-Turk, Vlad went in the opposite direction. When the Turks started advancing across Europe with their eye on Italy, Pope Pius II started recruiting his first line of defense. While many European leaders were unsure that the Turks were a threat, Vlad was more than happy to take up the sword—and the stake—to stop them. It was with the backing of the Church that Vlad stopped the practice of paying an annual tribute of soldiers to the Turks and started impaling them on stakes to send a very clear message. In six years, he put somewhere around 20,000 Turks to death, while Pius II wrote of his military genius and devout ways. It was only after Vlad’s death that the full account of the atrocities committed got back to the Pope, and by the time Pius II wrote his autobiography, his thoughts on the Wallachian ruler were quite different.

3 No One Knows How He Died . . .

After retreating across the Carpathian Mountains, Vlad spent 13 years as a prisoner of Matthias Corvinus. He was released in 1475 and made one last bid to reclaim his throne. He did—briefly—but died sometime around the end of 1476 under unknown circumstances. One story says that he fell in battle when his forces were ambushed by the Turks. Others suggest that his own men killed him, either accidentally mistaking him for a Turk or delivering the killing blow on purpose. After all, his cruelty was legendary, and he had just retaken his throne. Some stories suggest that he was assassinated by men who would rather not go back under his rule.

2 . . . Or What Happened To His Body

There are even more stories about what happened to Vlad’s body. According to most sources, he was beheaded, and his head was sent to Sultan Mehmed as proof of his death. The rest of his body was reportedly taken to Snagov Church. Stefan the Wanderer suggests that he didn’t ultimately rest there and that his body was then taken to Constantinope, then onto Sveti Georgi, a Bulgarian monastery, where monks had supposedly hoped to somehow save his soul. Snagov has been excavated, and the only bones found were mostly of horses. There is no shortage of fringe theories about Vlad’s final resting place. One student from the University of Tallinn claimed that her finding of a dragon-like creature in an Italian church meant that he was buried there, likely after his death was faked and he was ransomed to his daughter in Naples. (Spoiler alert: He wasn’t.)

1 Some Tales Describe Him As A Just Ruler

Vlad Tepes’s rule absolutely was filled with horrific acts, but he enacted a handful of policies that made some contemporaries paint him as a just ruler. Oral traditions tell of a ruler who maintained order by handing out punishments with an iron fist, seizing land and wealth from the disloyal, and rewarding the loyal. Stephen the Great of Moldovia (an ally) wrote of Vlad’s methods as cruel but just, necessary for the protection of the institution he governed. Even as his war on poverty ended with the lower classes burned alive so they would no longer burden society, Vlad also cracked down on something that was crippling the economy—imports. Saxon German merchants were taxed heavily and restricted to selling in certain towns, and those who didn’t listen died. He executed huge numbers of boyars with ideas for the redistribution of wealth and would be attributed as saying, “My sacred mission is to bring order . . . There must be security for all in my land.” Read More: Twitter