10 Ursula Kemp

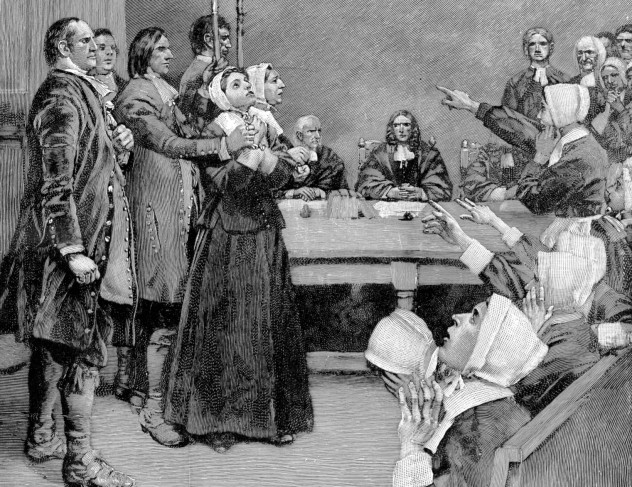

Ursula Kemp was put on trial on March 28, 1582, with 13 other women suspected of witchcraft. According to the charges, Kemp, a village midwife, had cursed a mother who had chosen the services of a different midwife. Not long after the baby was born, it reportedly died after falling out of its cradle. Remembering the heated words that had been exchanged between the two women, the local magistrate targeted Kemp with accusations of witchcraft. Ursula was accused of keeping several familiars, including a black toad named Pygine and a gray cat named Tiffin, whom the witch was rumored to feed cake, beer, and her own blood. Her eight-year-old son was coerced into testifying against her, and several others came forward to claim that her curses had led to the deaths of other locals. Ursula and one other woman, Elizabeth Bennett, were found guilty and hanged, while the others were given leniency for their supposed crimes. The records aren’t clear about where the women were executed after they were tried and convicted, but their story didn’t end with their deaths. In 1921, a local St. Osyth man discovered two badly damaged skeletons in his yard while doing construction work. Because they weren’t buried in consecrated ground and the Kemp legend was still familiar, he naturally thought they were the skeletons of the witches—and promptly started making some money by inviting people to view them. A mysterious house fire in 1932 put an end to the business, and the skeletons were reburied. They were exhumed again when the area was redeveloped. After a brief stay in a witchcraft museum, the remains thought to belong to Ursula ended up in the home of an artist, displayed beside the preserved body of a local beggar. Finally, a documentarian interested in uncovering the forgotten stories of 16th- and 17th-century convicted witches negotiated for the skeleton to be returned to St. Osyth. Examination of the bones found that it’s the right age to be Ursula. There are trace remains of iron nails still in her bones. After centuries, Ursula was finally laid to rest in 2011.

9 Hypatia

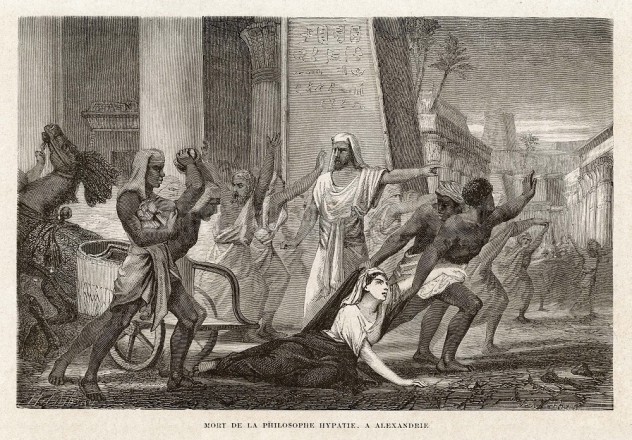

Hypatia was born in the fourth century. Her father was the director of the Library at Alexandria, and she grew up immersed in astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy. A brilliant teacher, lecturer, and thinker in her own right, her memory was resurrected in the 19th century as a tragic figure who was murdered because of superstition. The myth and history of her life have become almost impossible to separate. Historians believe that her death came after accusations of witchcraft and sorcery. The circumstances surrounding her death are complicated. At the time, Christianity was a blossoming young religion that was quickly threatening the old pagan ways, and Hypatia had so much influence and knowledge that many considered her dangerous. Cyril, a high-ranking patriarch within the Church, clashed constantly with the prefect Orestes as they argued about how much influence the Church should have over government matters. In 414, conflict reached a high point when Orestes refused Cyril’s attempts at a peaceful solution. Cyril’s followers became convinced that Hypatia had something to do with the failed attempt at bringing the conflict to an end, and rumors about Hypatia’s knowledge of witchcraft and sorcery began to spread. She was accused of casting spells and forcing her will over the entire city. It wasn’t long after the rumors started that the people took justice into their own hands, dragging her from her chariot one day as she headed to the library and flaying her alive with shells and broken pieces of pottery. What little was left of her when they were finished was burned.

8 Giovanna Bonanno, The Old Vinegar Lady

In 1788, everyone in Palermo knew that Giovanna Bonanno was a witch. She was old, she was a beggar, and she possessed the secret knowledge of how to concoct deadly spells and potions. Bonanno might not have been communing with the devil or casting spells by the light of the full Moon, but she had something even better—a real poison that worked. According to the story, she heard about a child who had nearly died after drinking a potion that was commonly used to kill lice. Based on her clientele and the reasons they usually came to her—to get rid of someone—she decided that she could use a tried-and-true poison. It became her “mysterious vinegar liquid.” After testing it on a stray dog, she spread the word that she had a simple food additive that could be slipped into anyone’s dinner for an inexplicable and untraceable death. Perhaps best of all was that the right dose would cause the victim to waste away, retaining enough strength to receive communion and last rites and ensuring that the poisoner didn’t have to bear the guilt of damning the soul as well as killing the man. When Bonanno was finally put on trial, the result was about 1,500 pages of court documents. The original potion maker—who only ever wanted to kill lice—was called into the court and asked to replicate the formula to demonstrate that it wasn’t witchcraft after all. Bonanno claimed that her potion and the lice potion were entirely different, but she also repeatedly testified that she didn’t know anyone who was in the business of practicing magic. The trial became a question of witchcraft versus traditional murder. Bonanno was eventually tortured, found guilty, and executed on July 30, 1789.

7 Thomas Doughty

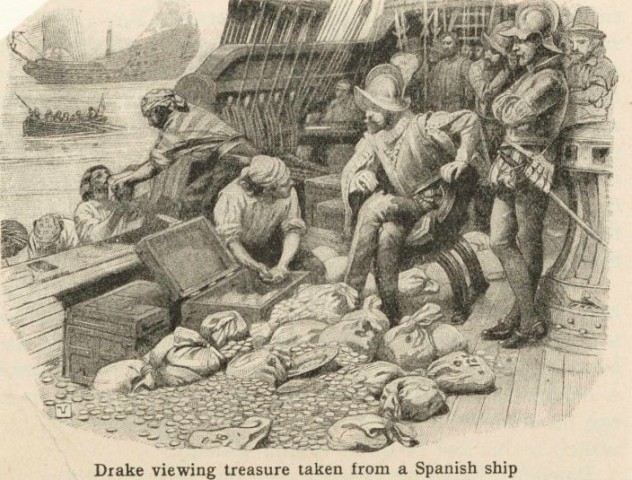

There are a couple different accounts of how Thomas Doughty met his end, but the general idea is the same—he challenged Sir Francis Drake. In 1577, Drake, Doughty, and some other mariners left Plymouth and headed south. They captured a few Spanish and Portuguese ships along the way, one of which was renamed the Mary and put under Doughty’s command. The whole journey was tarnished with bad luck, from storms that damaged their ships to unrest among the men. That unrest had in no small part been encouraged and spread by Doughty. Drake attempted to head the mutiny off, giving Doughty his own ship and every chance necessary to prove his loyalty to his captain, but he never did. Doughty continued his efforts to rouse the men on all the ships in the fleet into a mutinous condition. After weeks of problems with the crew, ships that disappeared in the night, and storms that struck out of nowhere, Drake was convinced that the ill-tempered, foul-tongued Doughty wasn’t just a problem—he was a practitioner of black magic. He was clearly trying to sabotage the mission, and he needed to be dealt with. Drake called together his crew and arrested Doughty and his brother John. Drake insisted that Doughty was in league with the devil and that his sorcery and witchcraft were putting everyone on his ships in danger. The trial, though, was officially for mutinous conduct, and Doughty was found guilty. Doughty had his last meal and asked Drake to forgive anyone suspected of having been in league with him. Drake agreed, and Doughty was beheaded.

6 John And Elizabeth Middleton

The fear of witches and witchcraft also hit Bermuda. In May 1653, John Middleton’s trial had taken something of a weird turn. In 1652, locals of Bermuda heard John Middleton confess that he was a witch—so they said. His wife, Elizabeth, had been accused of witchcraft herself and was very vocal about her husband’s participation in the occult. In December, she was convinced that if there was a witch in town, it was him, not her. She was so convincing that by the time his trial came around, even John was almost certain she was right. According to the accusations, John had bewitched a local man who had been living in the governor’s home. The man, John Makeraton, was so out of sorts that he needed to be restrained and jailed for his own protection. Witnesses including a young boy named Symon claimed that Makeraton was being plagued by a huge, black, shadowy figure with the vague shape of a man. Makeraton gave the same description of the thing that was haunting him, reporting that the demon “sate upon him very heveyley & asked him is he would love hym & he answered noe.” When it came to his trial, John uncertainly confessed even though his wife recanted her previous statement about his guilt. At first, the jury accepted her statement as an attempt to divert attention away from the accusations that had been leveled against her, but John failed his trial by water. (In this trial, witches float, as John did; innocent people sink and drown.) He had other strikes against him as well. He knowingly stole a turkey, and he had admitted his adulterous affairs. Afterward, he confessed to being a witch even though he hadn’t known it, and his appeals for mercy were ignored. He was hanged only a few days after the trial concluded.

5 Leatherlips

Leatherlips was a turn-of-the-century chief of the Wyandots, a Native American tribe forced from their land after a conflict with the Iroquois. Moving into Ohio, they found more conflict with white Europeans who were already there. Conflict led to war, and that war led to the defeat of the Wyandots. They were offered a treaty that laid out guidelines for the tribe to coexist with the other settlers. The treaty specified boundaries and land rights, and while many Native American leaders refused to even attend the meeting, Leatherlips didn’t just attend—he signed. That was in 1795. At the same time, Tecumseh and the Shawnee were fighting to keep the land he had just essentially given away. Many felt that signing the treaty was a huge step in the wrong direction, and the action Tecumseh saw as outright defiance was causing him to lose his influence over other tribes. As things continued to go downhill, Tecumseh and his supporters leveled charges of witchcraft against Leatherlips. In 1810, they captured Leatherlips and several of his men, claiming that he had delivered illness and death to his people. For the accusers, writing down a name and putting it on a paper treaty was nothing less than witchcraft. Literacy wasn’t only frightening because of superstitious reasons—although some had dreams warning against learning to read and write. Writing allowed the invading armies to exchange information, to create records of their enemies, and to record who was related to them, which gave them a massive advantage. Leatherlips was executed while kneeling before his grave. After he was killed with blows to the head with a tomahawk, the sweat on his neck was declared proof that he was guilty.

4 The Witches Of Belvoir

At the start, the story of the witches of Belvoir is pretty standard stuff. It was 1619, and the Earl of Rutland had just lost his two sons. Blame fell on two girls who were recently fired from the family’s service because of speculation that they were stealing from their employers. Their mother was also accused of involvement with the witchcraft, but she died before the trial. The trial was quick. The sisters were found guilty and hanged at Lincoln Castle. The execution of Margaret and Philippa Flower was a horrible affair. As they walked to the gallows, they were invited to say the Lord’s Prayer one last time. Both stumbled over the words, which those in attendance took as proof that they were so deeply involved with the devil that they could no longer speak holy words. They weren’t so much hanged as slowly strangled, then buried in unmarked, unconsecrated ground. The boys they supposedly killed were buried, and the family’s monument reads: “Two sons—both died in infancy by wicked practice and sorcery.” Today, historians think that they’ve found evidence that there was more at work in the accusations against the girls than just fear of witchcraft. The Earl of Rutland also had a daughter who had caught the eye of the Duke of Buckingham. The duke wanted to marry her, but with male heirs in the family, she didn’t stand to inherit much. The theory is that the Earl of Rutland got rid of his own sons and blamed their deaths on witchcraft.

3 Ruth Osborne

In 1751, John Butterfield, a cattle farmer in Tring, Hertfordshire, became convinced that the elderly Osborne couple was responsible for the end of his livelihood. He accused Ruth and John Osborne of bewitching him and causing the death of his cattle. Butterfield spread rumors among his neighbors that there were witches in their midst. Even though local authorities tried to place the Osbornes in protective custody, Butterfield succeeded in amassing a mob of thousands to attack them. At the head of the mob was a butcher named Thomas Colley. Colley, drunk on beer that Butterfield had provided, led the charge that seized the Osbornes and forced them to undergo a trial by water. Ruth died after the ordeal. There had been no proof and no legal trial. Authorities had a murder on their hands. Colley was arrested and put on trial for the murder of the old woman. With the mob of thousands that had been witness to it, there was no question of his participation. He was found guilty and hanged for murder, but there was a widespread belief that justice hadn’t been done with the second death. Locals thought that Colley should have been recognized for freeing Hertfordshire from the grip of an evil witch.

2 Christence Kruckow

Christence Kruckow was a young noblewoman of Denmark in the 1580s. She was sent to spend her youth in the household of Sir Eiler Brockenhuus and found herself at the center of accusations of witchcraft by two servant girls. After her host’s marriage to Anna Bille was followed by the deaths of 15 infants, the household started looking for a likely suspect. One of the servants was originally accused, but she confessed that she had been forced to help Christence with her wicked spells, which had started from the earliest days of the wedding. Two of the servants were executed as witches in 1587, but Christence’s status saved her life. She left the house and moved to Aalborg, but accusations followed her. Supposedly, she and her sister had a quarrel with a neighbor named Maren. The girls were accused of being in attendance when a woman gave birth to a wax idol, which they named Maren and used as a vehicle for their curses. Again, servants were executed and Christence escaped. In 1618, she was accused again of using a similar wax idol to bewitch and attack a local vicar’s wife. This time, she went in front of the House of Lords in Copenhagen. Her titles and nobility were revoked, and she was ultimately executed. Her nobility did grant her one final advantage; she was beheaded instead of burned at the stake so that she could receive a proper burial. The University of Copenhagen inherited her fortune.

1 The Pappenheimer Family

Perhaps one of the most heartbreaking tale of executions at the end of a witchcraft trial is that of the Pappenheimer family. The family—parents Paul and Anna and their children, 22-year-old Gumpprecht, 20-year-old Michel, and 10-year-old Hansel—were arrested in February 1600. Originally, the charges were petty crimes you might expect from a destitute family of the 1600s. The Duke of Bavaria decided to make an example of the family and had them questioned under torture. As they were tortured, a saga of witchcraft and association with the devil started to unfold. When they were ordered to confess their crimes, they started to recount terrifying acts. They had flown on sticks and met with the devil—they had even had sexual relations with the demon. They were given the power to create magic potions and to control the weather, and they did it all by killing people and eating their corpses. They were robbers, murderers, and thieves, doing the devil’s bidding. The entire family was executed on July 29, 1600. Having already endured unimaginable torture, they were put on display before a crowd of thousands. Red-hot pincers tore at their flesh. The boys watched as their mother’s breasts were cut off, and the bloody tissue was then rubbed over their faces. The youngest watched as his family was burned alive, and then he was burned, too. The executions marked a turning point in Bavarian law. Before then, there was no standard of hunting and executing witches because there was some debate about whether they were dangerous enough to warrant the trouble. Many were, after all, folk healers and harmless old women. The confessions of the family suggested otherwise. In 1611–1612, the Territorial Ordinance against Superstition, Magic, Witchcraft, and Other Criminal Arts of the Devil made it clear that witchcraft was very, very serious. Witches were to be hunted and wiped out. The law was in effect for a shockingly long time—until 1813. Read More: Twitter