Well, almost everyone. Every so often, a rogue writer comes along with big dreams and a sneaky scheme, duping critics and readers alike. And while some maintain honesty is the best policy, that certainly wasn’t the case for these 10 literary hoaxers.

10 Naked Came The Stranger

Naked Came the Stranger was a novel written in 1969 by a group of reporters at Long Island Newsday. These journalists were sick of poorly written, smutty novels becoming bestsellers. Wanting to prove a point about the public’s appetite for trash, editor Mike McGrady developed the idea for the hoax, coming up with the novel and its tawdry plot. The novel centered on a suburban woman’s sexual liaisons, and each chapter focused on a different escapade (usually with a different man each time). Each of the reporters involved knew the main outline of the story and wrote one chapter each, making the plot deliberately inconsistent. In fact, submissions that were written too well were immediately rejected. McGrady’s sister-in-law played the part of the book’s author, Penelope Ashe, “a demure Long Island housewife who thought she could write as well as J. Susann.” She even posed for photographs and met with the publishers. The book ended up selling 20,000 copies before McGrady and his colleagues came clean. Nevertheless, by the end of 1969, the novel had spent a total of 13 weeks on The New York Times best-seller list, and the stunt had made headlines around the world, making Naked Came the Stranger a runaway success.

9 I, Libertine

In the 1950s, Jean Shepherd was the host of a late night radio show, and he inspired extremely loyalty in his listeners. Shepherd even described his fans as “night people,” because they always tuned in to his peculiar broadcast in the middle of the night. It also didn’t hurt that they were, in Shepherd’s view, a rather non-conformist bunch of people. Indeed, Shepherd was a favorite among the Beat movement, jazz artists, and young creative people. Even Jack Kerouac himself was an admirer. One day, Shepherd went down to a bookstore in search of a particular title. Not being able to find what he was looking for, Shepherd asked the clerk for help. However, the clerk insisted the book couldn’t exist, as it didn’t appear in any of the publisher’s lists he’d ever seen. Still, Shepherd was convinced the book was real . . . and that’s when his imagination went wild. With the help of the night people, he decided to pull a bizarre media hoax on the so-called “day people,” as well as New York pretension. Thus, Shepherd encouraged his listeners to stop by their local bookshop and ask for a book that didn’t exist. The fake title was I, Libertine, and the name of the supposed author was Frederick R. Ewing. Extra information about the author was also cooked up. Ewing was supposedly a retired Royal Navy commander who specialized in 18th-century erotica. (He’d also apparently done a BBC series on the subject.) Listeners followed Shepherd’s lead, and soon bookstores were flooded with customers asking for I, Libertine. These requests happened abroad, too, since some of the night people traveled for work. Confused booksellers began contacting publishing houses to find out more about this novel, and libraries began placing orders for this mysterious book. The hoax, however, did not stop there. A student wrote a paper on I, Libertine and received a “B+.” The night people created card files for the book and placed them in libraries all over the country. A New York gossip columnist said he’d had lunch with the author. The novel even hit The New York Times Book Review of newly published books, and all that time, it didn’t even exist.

8 My Own Sweet Time

My Own Sweet Time was an autobiography that was supposedly written by Wanda Koolmatrie, a part-aboriginal woman. The book tells about her experience growing up in South Australia with white foster parent, and it won the Dobbie Award for a first novel by a woman writer. It was even used in the New South Wales HSC English exam in 1996. However, as you might’ve guessed, it was later revealed that My Own Sweet Time was actually written by a white male named Leon Carmen. In 1997, Carmen admitted to writing this award-winning novel, causing quite an uproar in Australia’s literary establishment. The front page headline of Sydney’s Daily Telegraph dubbed Carmen as the “Great White Hoax,” the book was withdrawn from sales, and the award money was retrieved. Even Carmen’s agent was raided by police. Trying to justify his motives, Carmen said that Australians discriminate against white men. According to the hoaxer, critics and readers instead preferred female, aboriginal, and immigrant-descended writers.

7 The Hand That Signed The Paper

The highly successful novel, The Hand that Signed the Paper, was written by Helen Demidenko, a woman who claimed to be of Ukrainian heritage. The plot of the novel is centered on a Ukrainian family whose members participated in the Holocaust. Demidenko claimed she relied heavily on her father’s memories of what the Ukrainian famine was like. In addition to surviving such a calamity, her dad was also supposedly an illiterate taxi driver. In 1993, the manuscript won the Vogel Award for unpublished young authors, and in 1994, it was published by Allen & Unwin. The Hand that Signed the Paper then quickly went on to win the Miles Franklin Award, as well as the gold medal from the Australian Society for the Study of Australian Literature. However, some people criticized the book for its anti-Semitic values, but the worst was yet to come. After Demidenko won the Miles Franklin Award, the truth about her past quickly unraveled. It was revealed that she was actually the daughter of British migrants. And her name wasn’t Helen Demidenko, but instead, she was really Helen Darville. In 2006, Darville—now known as Dale (her married name)—wrote a full account of the affair. She claimed that she wrote The Hand that Signed the Paper in order to protect her source, a Ukrainian war criminal that only had six months to live, due to cancer. However, she also claimed that the book was a hoax aimed against the political left, which she apparently considered spineless.

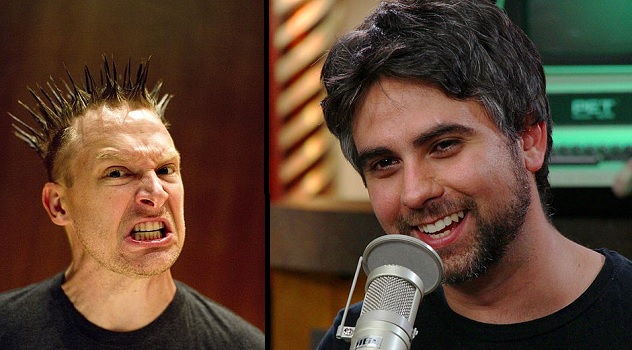

6 The Diamond Club

Basically a modern-day Naked Came the Stranger, The Diamond Club is an e-book supposedly written by Patricia Harkins-Bradley, but in actual fact, it was created by Justin Young and Brian Brushwood of the NSFW Show podcast. The book’s plot was submitted by their listeners and, upon the duo’s request, included lots of sex. The Diamond Club made it to number four on the iTunes store’s top-seller list, topped only by the Fifty Shades of Grey trilogy. Brushwood had previously written and published a few books of his own, including Scam School Book 1: Smoke and Scam School Book 2: Fire. However, he found it annoying how his second book was dominated by novels that appeared to sell just because they looked like Fifty Shades of Grey knockoffs. Irritated, Brushwood and Young decided to pull a hoax, or as they call it, a “social experiment.” The Diamond Club was a real success, and even though it sold for only 99 cents, it made more than $17,000 in three days after it was published. Interestingly, most fans of The Diamond Club didn’t even realize that the book was a hoax, and they left real, genuine reviews.

5 The Autobiography Of Howard Hughes

In 1971, Clifford Irving, a successful author, was struck by the idea of writing a fake autobiography for Howard Hughes, the eccentric billionaire who hadn’t been seen in public for 15 years. Counting on Hughes’s reclusiveness, Irving figured the billionaire wouldn’t come forward to renounce the fake book. To convince the publisher, McGraw-Hill, of the project’s legitimacy, Irving actually forged letters from Hughes, copying handwriting that had appeared in a Newsweek article. The fake letters claimed Hughes would be willing to cooperate with Irving on a book about his life, but the project should remain a secret. The only person Hughes wanted to deal with, even when it came to financial matters, was Irving. As for “research,” that fell to Irving’s writer friend, Dick Suskind. McGraw-Hill and Irving agreed that Hughes would receive $750,000, and Irving himself would take home a tidy $100,000. Irving’s wife, Edith, then flew to Switzerland where she opened an account under the name of “Helga R. Hughes.” This account was where the $750,000 ended up. Over time, Edith withdrew money from the Swiss account and carried it to the Spanish island of Ibiza. There, in their farmhouse, Irving hid his ill-gotten gains. Now, originally, Irving had pitched the book as a series of interviews with Hughes, but Irving and Suskind later changed their minds, thinking an autobiography would be better. A forged note from Hughes, saying he was okay with the change in plans, was soon produced. Shortly afterward, the manuscript was delivered to McGraw-Hill. The stories that appeared in the autobiography were outlandish, to say the least. For example, one tale has Hughes engaging in secret combat missions with the RAF in World War II. But shockingly, no one was suspicious of this alleged autobiography. When the book’s publication seemed inevitable, Frank McCulloch, a Time-Life journalist who’d interviewed Hughes 14 years previously, received a phone call from a man claiming to be the billionaire. The man said that he hadn’t cooperated with Irving. The call really was genuine, but after examining the manuscript, McCulloch decided the book was the real deal, and the phone call had been a fake. However, just before the scheduled publication, Hughes called from his Bahamian hotel and held a televised press conference. Of course, Irving claimed that the voice didn’t belong to Hughes, but Swiss authorities investigated the “Helga R. Hughes” bank account, and soon learned that it actually belonged to Irving’s wife. Dick Suskind was sentenced to six months in prison, and Irving was sentenced to two years. His wife was also sentenced to two years, but her sentence was suspended after only two months.

4 The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things And Sarah

The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things and Sarah were supposedly written by J.T. LeRoy, a literary sensation in the late 1990s and early 2000s. His books were autobiographical fiction, and they were supposedly inspired by his troubled childhood. As a kid, LeRoy worked as an underage transvestite prostitute, alongside his drug-addicted, prostitute mother. He also became addicted to heroin, and at the mere age of 13, ended up on the streets of San Francisco. According to LeRoy, he had his first sexual experience at around age five or six, and he was regularly beaten and raped. Then, salvation came. LeRoy was found by a social worker who introduced him to a psychologist. The psychologist encouraged LeRoy to write, and soon J.T. realized he was quite good at it. In 1997, at the age of 17, LeRoy published his first piece of writing in an anthology called “Close to the Bone: Memoirs of Hurt, Rage, and Desire.” It was about dressing up like his mother and seducing her boyfriend. In 2000, he published a novel called Sarah, and a year later, he published a collection of stories titled The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things. The books were publically acclaimed, and LeRoy became friends with celebrities. And while he was at first reluctant to be seen in public, he did eventually make appearances. However, it was soon discovered that LeRoy was a pseudonym for Laura Albert, a married woman who was 15 years older than LeRoy. The author’s public appearances were made by none other than her sister-in-law, Savannah Knoop. Nevertheless, it would be unfair to say that Albert had no idea what she was talking about in her books. Just like LeRoy, Albert was abused as a little girl, and as a teenager, she’d become a ward of the state and had to live in a group home.

3 Fragments

Binjamin Wilkomirski’s Fragments is a memoir that deals with his childhood in the Nazi concentration camps of Majdanek and Auschwitz. Fragments was published in 1995, and it caused quite a sensation in Germany. Shortly afterward, the memoir was translated into 12 languages, and in 1996, it was published in both the UK and the US. It also won the National Jewish Book Award in America, the Jewish Quarterly Literary Prize in Great Britain, and the Prix de Memoire de la Shoah in France. The memoir recounted the story of a young Jewish child whose family was slaughtered in the Latvian city of Riga. After the massacre, he was taken to the death camps in Poland. There, Wilkomirski survived the war, as well as the vile conditions of the camps. When it was all over, he was taken to an orphanage in Switzerland and adopted by a Swiss couple. The book was sensational, the sales were high, and readers and reviewers were both impressed and sympathetic. Wilkomirski toured the world and recounted his story to emotional audiences, interviewers, and journalists. Then, a young Swiss Jew named Daniel Ganzfried was sent to interview Wilkomirski. Ganzfried had written an account of his father’s experience in Auschwitz, and upon hearing Wilkomirski’s account, he felt something was off with the guy’s story. Ganzfried dug deep, and he soon discovered that Wilkomirski was born in a Swiss village close to the capital of Berne. His mother was unmarried, so she placed her son in an orphanage, where he was adopted and taken to Zurich. Thus, it was revealed that Wilkomirski was neither Latvian nor Jewish. In fact, his name was even made up. Binjamin Wilkomirski was actually Bruno Dossekker. And of course, he’d never been in a concentration camp. Ganzfried’s expose was published in a Swiss newspaper, leading to Dossekker’s breakdown. He refused to respond to the accusations, and people soon viewed his book for what it was—a piece of fiction.

2 Famous All Over Town

Famous All Over Town was a novel written by Danny Santiago. In his book, Santiago wrote about life in East Los Angeles, and the 1983 novel received praise for its awareness of the troubled Mexican-American culture. In 1984, the book won a Rosenthal Award for literary achievement sponsored by the American Academy and Institute of Arts. Of course, the book might’ve received a bit more criticism if everyone had known that Santiago was actually Daniel Lewis James, a Yale graduate and son of a wealthy Kansas businessman. He’d also helped Charlie Chaplin write The Great Dictator. However, at one point, he’d been a member of the Communist Party. As the fear of communism spread through Hollywood in the 1940s and ‘50s, both James and his wife were subpoenaed to testify in front of the House Un-American Activities committee. Shortly afterward, James was forced into writing B-grade movies, and he eventually disappeared from the movie scene completely. James then spent the next 25 years in East Los Angeles, working as a church social worker. There, he became enchanted with Latin culture, and he was inspired to write as Danny Santiago. The publication of these stories was a result of chance and luck. James and his wife had rented a Hollywood home from the writer John Gregory Dunne, and when Dunne saw the stories, he sent them to his agent in New York. However, it was also Dunne who disclosed the deceit when writing in The New York Times Review of Books in 1984. But James was happy that the charade had come to an end, because now he was finally free to talk about his books with others.

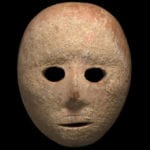

1 The Voyage And Travels Of Sir John Mandeville, Knight

The Voyage and Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Knight was supposedly written by the titular Sir John Mandeville, the greatest traveler of the Middle Ages. The book was extremely popular in its day and was “a household word in 11 languages and for five centuries.” The book was considered a guide for pilgrims to Jerusalem, and while the first part does indeed focus on the Holy Lands, the second half deals with the eastern world beyond the borders of Palestine. However, it’s now known that the tales found in The Voyage and Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Knight are actually stories selected and copied from the narratives of genuine travelers. However, they’re all embellished with Mandeville’s additions. In other words, nobody knows if the Mandeville actually traveled at all. In the book, Sir John describes himself as a knight of St. Albans, but the man’s real identity is unknown. The 14th-century chronicler Jean d’Outremeuse of Liege stated that the true author was a physician named Jean de Bourgogne. Others believed that d’Outremeuse himself was the actual author of the book. However, these speculations have been debunked, and the true writer remains shrouded in mystery to this day. A student from Ireland in love with books, writing, coffee, and cats.