10The Nine-Year-Old Author

After her mother died in 1917, 36-year-old Daisy Ashford was going through her papers when she discovered a relic from the past. It was a book Daisy had written as a child, back when she wanted to be an author. It was called The Young Visiters (give her a break, she was nine), and the story followed an “elderly man of 42” named Alfred Salteena who wants to become a gentleman and marry his young ward, Ethel Montecue. But Ethel loves Bernard Clark, a friend of Mr. Salteena who’s helping him in his quest to join the upper classes. Hijinks and social misunderstandings ensue. Sure, it wasn’t all that original, but when Daisy published it nearly 30 years later, complete with spelling errors, the book became a best seller. Critics called it “one of the most humorous books in literature” thanks to its absurd adjectives, terrible typos, and extreme earnestness. This was a nine-year-old trying to sound like an adult. Daisy loved using words like “sumpshous” and “aristockracy,” and her dialogue was pretty comical. “You are to me like a Heathen god,” whispers one lover to another. She was also incredibly fond of describing everything, right down to a man’s “nice thin legs in pale broun trousers and well fitting spats and a red rose in his button hole and rarther a sporting cap which gave him a great air with its quaint check and little flaps to pull down if necesarry.” In fact, some people thought her book so childishly brilliant that perhaps J.M. Barrie was the real author. He’d penned the introduction. But no. The Young Visiters was written by Ms. Ashford, and it went through eight printings in its first year alone. Copies were given to wounded World War I vets to lighten their spirits, and one book even made its way to Queen Mary. And The Young Visiters continues to delight audiences in the 21st century. Back in 2003, BBC released their own adaptation starring Jim Broadbent and Hugh Laurie.

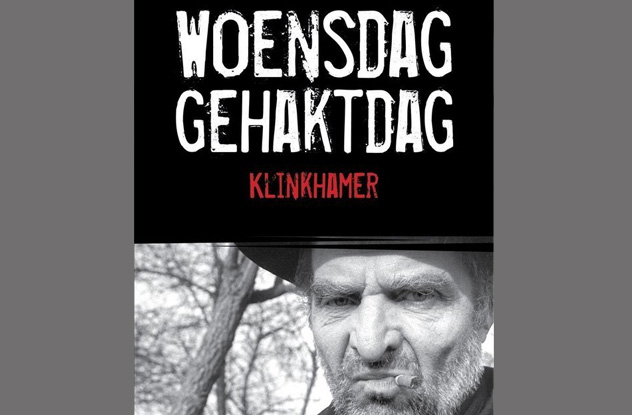

9The Author Who Murdered His Wife

Remember when O.J. Simpson published a book describing how he hypothetically murdered Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goodman? He wasn’t the only author who copped to killing his wife in book form. Only Richard Klinkhammer’s story was a bit more . . . creative. Klinkhammer was a Dutch author with an alcohol problem and a wife named Hannelore who mysteriously disappeared in 1991. Cops considered Klinkhammer their top suspect, but after turning his house and property upside down, they had to give up on the case. They just couldn’t find any evidence. They couldn’t even find a corpse. A year later, Klinkhammer wrote a story about his runaway bride, a novel called Wednesday, Ground Meat Day. The book was divided into seven gory segments that detailed the different ways he might’ve murdered his wife. In one chapter, he even sticks her in a meat grinder and then feeds her flesh to birds. His publisher thought it was a bit much. Also, it was horribly written. However, word of his sensational story spread throughout the Dutch literary scene, and Klinkhammer became a celebrity. He sold his home to a young couple, moved to Amsterdam, and started popping up at literary parties and appearing on TV shows. As he enjoyed his newfound notoriety, the couple who’d bought his house decided they wanted to make a few changes to the yard, like tearing down that old shed out back. When they dug up its concrete foundation, they discovered a skeleton. When the cops picked up Klinkhammer, the author confessed that his book was an autobiography. But he hadn’t used a meat grinder. Instead, he’d bludgeoned his wife over the head. However, Klinkhammer got off pretty light. He was sentenced to six years behind bars and only served about half that. Even worse, after he got out in 2003, he actually found somebody who agreed to publish his nasty novel.

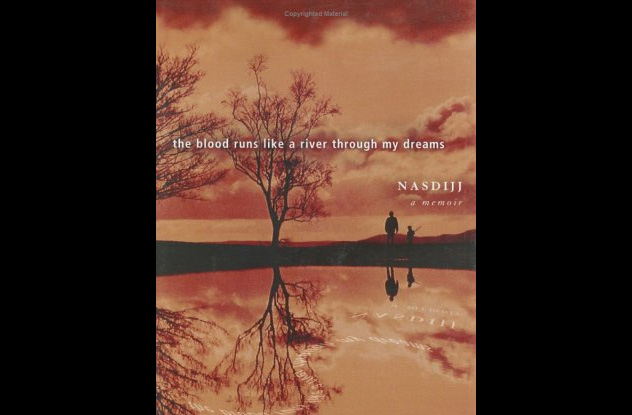

8The Fake Navajo

His name was Nasdijj, and his life was awful. Born to an abusive white father and alcoholic Navajo mother, Nasdijj lost his mother at age seven and was then raped by his dad. As a boy, he wandered from migrant camp to migrant camp, all while protecting his little brother. Eventually, he adopted a boy who suffered from fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), and after his son’s sixth birthday, he died in Nasdijj’s arms. Yeah, it was depressing stuff. And the critics loved it. In 1999, Nasdijj wrote about his son in Esquire, and the piece did so well that he earned a book contract. Soon, he’d written three memoirs, including one about how he adopted a young AIDS victim, only to watch him die, just like his first son. Nasdijj’s books earned international acclaim, and he even won a grant to help him continue telling stories about Navajo life. However, some were skeptical of Nasdijj’s stories—particularly Native Americans. Author Sherman Alexie suspected Nasdijj was borrowing stories of other Native American writers, including his. Navajo professor Ivan Morris also noticed troubling details like Nasdijj claiming his mother belonged to the Water Flowing Clan, a group that doesn’t exist. He was also concerned about the author’s name. According to the writer, “nasdijj” means “to become again.” According to the professor, there’s no such word in the Navajo language. Finally, in 2006, LA Weekly exposed Nasdijj as a fraud. His real name was Timothy Patrick Barrus. He didn’t have a little brother or son with FAS, never adopted a kid with AIDS, and wasn’t even a Navajo. He did, however, have a lot of writing experience. In a past life, Barrus wrote gay leather porn and even coined the term “leather lit.” And “Nasdijj” wasn’t his first hoax. Once, he wrote a novel about his time fighting in Vietnam, and as you’ve probably guessed, Barrus was never in the military. Barrus confessed to the hoax, claiming no one paid attention to his work until he invented Nasdijj. That’s equal parts tragedy and irony, as no one really pays any attention to him now, either.

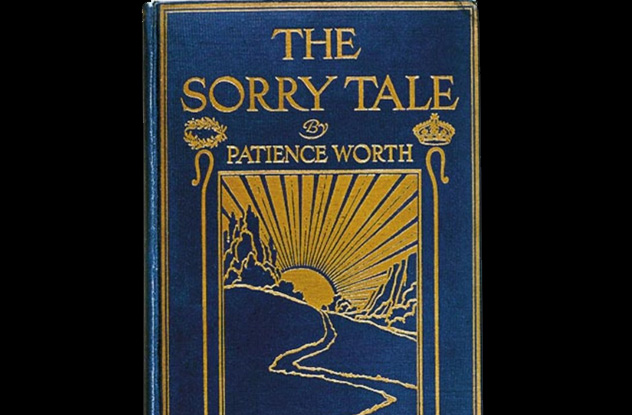

7The Writer Who Communed With A Spirit

There wasn’t anything special about Pearl Curran. Born during the Victorian Era, she dropped out of school at 13 after suffering a “nervous collapse.” She was a bit of a hypochondriac. She also hoped to become a singer, but those plans were shelved after she got married. Without any kids, she spent most of her time around the house, totally bored. That is, until she met Patience Worth. After Curran’s dad died in 1912, she tried to contact him with the help of a Ouija board. But instead of finding her father, she discovered a spirit named Patience Worth. In the 17th century, Patience had been a young Englishwoman who’d moved to America and ended up on the wrong side of a Native American knife. She wasn’t ready to move on to the afterlife. Instead, she wanted Pearl to help her become a famous author. Together, Pearl and Patience churned out nearly 40 million words. They wrote everything from short stories to plays, and Patience-Pearl even composed seven novels, the first of which was praised by the New York Times as a “feat of literary composition.” Pearl also invited guests to attend special seances in which she composed impromptu poems on the fly—with Patience’s help, of course. Skeptics were baffled by Patience-Pearl. How could she write so much amazing stuff so quickly? Was she writing stories in her subconscious? Did she have multiple personalities? And how did she know so much about the 1600s? She’d dropped out of school at 13. How did she know everything about 17th-century diets, customs, and wildlife? How did she know so much about places she’d never visited? Some say she had a photographic memory and could remember everything she read. Or maybe she was a really fantastic con artist. In 1919, Pearl wrote a short story called “Rosa Alvaro, Entrante,” and it was about a bored Victorian woman who uses a fake spirit guide to make her life more interesting. Perhaps Pearl Curran was writing from experience.

6The Infamous Winsted Liar

It was August 1895, and Lou Stone needed some cash. If only he could find a story. Stone was a Connecticut newspaperman, writing for the Winsted Evening Citizen. He knew the papers in New York would fork over $150 if he found something crazy enough to grab their interest, but things were slow in Winsted. So Stone made up his own story. The reporter whipped up the wildest tale imaginable, and when it went over the wire, editors in New York freaked out. Evidently, there was a hairy wild man running around the woods of Winsted. Journalists from the Big Apple rushed to the little Connecticut town and started interviewing everyone in sight. When the Winsted citizens heard a wild man was close by, people panicked. They suddenly remembered seeing a huge tusked man with Neanderthal arms lurking in the forest. Soon, posses were marching into the wilderness, armed to the teeth, hunting for the monster. They only found a donkey. Eventually, Stone confessed to his hoax, but instead of ending his career, the wild man made him a star. The “Winsted Liar” began cranking out a new article each week, each one crazier than the last. In one column, he wrote about a chicken that laid red, white, and blue eggs on the Fourth of July. He did another piece on a frog that downed a jug of applejack and broke into an amphibious rendition of “Sweet Adeline.” Stone also covered a Winsted cow that was accidentally locked in an ice house and, as a result, only gave ice cream for two straight weeks. His stories were wildly popular, and newspapers across the country regularly ran his columns. His articles made Winsted kind of famous, and his neighbors were so proud that they erected a billboard thanking Stone for putting their town on the map. In 1933, the “Winsted Liar” died, and the citizens honored the old fabulist by naming a bridge after him. Appropriately enough, the bridge ran over Sucker Creek.

5The Man Who Wrote Letters To A Serial Killer

Alabama native Sheila LaBarre moved to Epping, New Hampshire, in the late ‘80s. LaBarre quickly gained a reputation for pulling stunts like greeting deliverymen in the nude. People also thought it was suspicious when her elderly husband died in 2000. Some claimed LaBarre had poisoned the old doctor. After her husband’s death, LaBarre shacked up with a series of young men, including a young autistic man named Kenneth Countie. In 2006, Countie’s mother asked the Epping police force to check on her boy. He hadn’t contacted her in quite some time. When the cops showed up at LaBarre’s horse ranch, they found what was left of Countie . . . smoldering in a burn barrel. In addition to Countie, police also found the remains of a man named Michael DeLoge—plus several unidentified toes. After a weeklong manhunt, LaBarre was arrested for murder. Then TV reporter Kevin Flynn launched his letter-writing campaign. Flynn was hoping to befriend LaBarre so he could interview her for a book. Around Christmas, Flynn sent Sheila a letter, offering a sympathetic ear. Then, just like Flynn had hoped, LaBarre wrote back. Soon, the reporter and the killer were pen pals, swapping letters on a regular basis. And things took a flirtatious turn. LaBarre decorated her envelopes with intricate illustrations and even wrote a poem especially for Kevin. While Flynn insists there was nothing romantic going on, he does admit he probably encouraged her sweet-talking. Their relationship fell apart after LaBarre’s letters started arriving at Kevin’s work. His coworkers opened them and read them out loud for laughs, which humiliated Kevin. Even worse, Flynn tried to explain himself by writing a letter to a prosecutor, saying if he learned any key details, he’d share them with the district attorney. Thanks to that slipup, Flynn could now be called as a witness, and that majorly conflicted with his job as a reporter. Flynn was fired from his job and, right around this time, got divorced. He doesn’t think his relationship with LaBarre ended his marriage. Instead, he believes his unhappiness with life prompted him to start writing a serial killer. Whatever made him swap letters with a murderer, Kevin did publish his book. As for LaBarre, she’s currently serving two life sentences. They aren’t pen pals anymore.

4The Writer Who Predicted The Atomic Bomb

It was 1943, World War II was raging, and Cleve Cartmill had a story idea. After holding several jobs, the 36-year-old Californian, crippled by polio, was making his living as a writer. Now, he wanted to tell a story about a super bomb, a weapon so powerful it could wipe out thousands upon thousands of people. When Cartmill sent his query letter to John Campbell, editor of Astounding Science Fiction, he discovered his idea wasn’t all that original. When Campbell wasn’t running his magazine, he was reading scientific journals, so he knew scientists were making big advancements when it came to splitting the atom. In fact, he theorized scientists might soon make a bomb that could “blow an island, or hunk of a continent, right off the planet.” However, Campbell suggested it might work if Cartmill set his story on another planet. Inspired, Cartmill wrote “Deadline,” a short story where a “Seilla” agent must stop a “Sixa” bomb from destroying his alien world. (Read “Seilla” and “Sixa” backward, and you’ll see Cartmill wasn’t great at dreaming up sci-fi names.) During the writing process, Cartmill was in constant contact with his physics-savvy editor, asking for tips on how an atomic bomb might work and what its effects might be. “Deadline” was published in March 1944 and wasn’t popular. Of the six stories in the magazine that month, readers picked it as their least favorite. However, it did catch the attention of the US War Department. Special agents combing through Astounding Science Fiction were particularly interested in passages that contained spot-on descriptions of how the real-life—and totally top secret—atomic bomb actually worked. Concerned someone was leaking info, the feds investigated Cartmill and Campbell. Even though the editor explained that he’d figured it out on his own, the government was skeptical at first. They put both men under surveillance, investigated Cartmill’s friends (like Robert A. Heinlein and Isaac Asimov), and even recruited the author’s postman as a spy. Eventually, the War Department agreed “Deadline” was just a major coincidence, though they did ask Campbell to stop publishing stories about atomic weapons.

3The Scary Victorian Travel Guide Writer

Favell Lee Mortimer wasn’t a happy person. Born in London in 1802, Mortimer was raised a Quaker but fell in love with a young Evangelical. She eventually converted, but even so, her parents refused to let her marry the guy. Then the jerk ran off, married somebody else, and stopped talking to poor Ms. Mortimer. Depressed, she married an abusive reverend, and the man was such a monster that she spent most of her time hiding at her brother’s house. She was miserable. Her doctor even said she was the only person he’d met who wanted to die. But instead of using her pain to create great art, she decided to terrorize children across England. Favell Lee Mortimer published 16 books, starting off with The Peep of the Day. Written for four-year-olds, The Peep of the Day is Bible primer in the style of Roald Dahl. It’s the most gruesome book ever written for toddlers. For example, in one passage, she explains all the nasty ways a four-year-old could die: “How kind of God it was to give you a body! I hope your body will not get hurt . . . Will your bones break? Yes, they would, if you were to fall down from a high place, or if a cart were to go over them . . . If it were to fall into the fire, it would be burned up. If a great knife were run through your body, the blood would come out . . . If you were not to eat some food for a few days, your little body would be very sick, your breath would stop, and you would grow cold, and you would soon be dead.” Even worse are her three travel guides: The Countries of Europe Described, Far Off: Asia and Australia Described, and Far Off: Africa and America Described. These books were meant to give Victorian kids a glimpse of the outside world, which is a terrifying place. Hungarian swineherds will murder you with pigs, Sweden is full of bandits, and the Swiss snow will cause your house to collapse on your head. But wait, there’s more. According to Ms. Mortimer, the people of Iceland are incredibly filthy. Italians are “ignorant and wicked” Catholics who regularly “take out their knives and cut each other.” Evidently, “no people in Europe are as clumsy and awkward as the Portuguese,” but hey, that’s nothing compared to Asia. In Burma, the people “tell lies on every occasion,” and in China, “it is a common thing to stumble over the bodies of dead babies in the streets.” When she wrote her travel guides, Ms. Mortimer had only left England once to visit France and Belgium as a teenager. Of course, she probably wouldn’t want to visit anywhere else. The world is a scary place, and it’s probably best just to stay at home.

2The Author Who Lives Under Armed Guard

Roberto Saviano is a best-selling author whose first book was translated in 51 countries. It was even adapted into an award-winning film, but if you asked Saviano how he feels about his career, he’d tell you that he hates the book that made him famous. Saviano grew up in Naples, where innocent bystanders were gunned down in gang wars and houses were blown apart by Mafia bombs. He lived in a city where the mob stuck its dirty fingers into every pie imaginable, from garbage collection to bread production to gas distribution. Infuriated, Saviano spent five years researching the Camorra Mafia. He worked for a construction company owned by gangsters. He listened to police frequencies so he could show up at gangland murders and investigate crime scenes firsthand. The man even waited tables at a Mafia wedding, and in 2006, he published Gomorrah, a savage expose of the Camorra mob. At first, gangsters enjoyed reading Saviano’s book and even gave copies away as gifts. They enjoyed the publicity and notoriety, until the book spread across the world. Soon, Gomorrah had sold over 100,000 copies, and now people across the planet were reading about their activities. They were out in the open and very ticked off. Saviano started getting death threats. His mom even found a picture of Saviano in her mailbox, complete with bold letters spelling out “Condemned.” When two powerful crime lords were put on trial, their lawyer read a document blaming Saviano for their arrest. An informant warned authorities that Saviano’s days were numbered. In a way, they were. Suddenly, Saviano found himself surrounded by bodyguards. If he wanted to drive down the street, his entourage traveled in two armored cars. He couldn’t stay in Naples as it was too dangerous, and he was soon traveling the world, spending nights in hotels or police barracks. For the past eight years, he’s lived under 24/7 protection, and his schedule is planned out to the precise minute. When he visits other countries, he isn’t even allowed to walk outside on his own. If he could go back in time, Saviano swears he wouldn’t write Gomorrah. “I realized the dream of a writer,” he mused, “an international best seller. But my life has been poisoned.”

1The Writer Who Baffled Intelligence Agents

Gerard de Villiers was a French superstar. Between 1965 and 2013, he thrilled readers with his Son Altesse Serenissime novels, a series starring the superspy Malko Linge. An Austrian aristocrat who freelances for the CIA, Malko lives in a castle, speaks multiple languages, and wears tailor-made alpaca suits. And when it comes to sex, he makes James Bond look like Mother Teresa. De Villiers published 200 novels before he died at 83, churning out four to five books a year. Thanks to their high-paced action and incredibly graphic sex scenes, the SAS series sold over 100 million copies before de Villiers died. De Villiers wasn’t beloved by the French literati, but while critics turned up their noses, the novels were majorly respected by one particular group of readers: real-life spies. Intelligence officers pored over the pages, and CIA agents recommended that analysts check out these action-packed stories. Even French officials like Hubert Vedrine and Nicolas Sarkozy were big fans. So many high-profile people were interested in these books because reading a Malko Linge novel was like reading a newspaper . . . before the news stories made headlines. In 2012, de Villiers published a novel focusing on terrorist cells in Libya, particularly ones in the city of Benghazi. The book also revealed classified information about the layout of the CIA’s Benghazi base. Six months later, actual terrorists attacked the CIA annex in Benghazi, eerily paralleling de Villiers’s novel. This wasn’t the first time de Villiers predicted the future or revealed secret info. In 1980, one novel predicted the assassination of Anwar Sadat. Another accurately profiled several secretive members of the Syrian government and prophesied an attack on a government building. A third novel detailed the real Syrian-backed plot to kill a Lebanese official and even contained a list of the actual assassins. Nobody aside from intelligence officers knew their names. Not until de Villiers published his book anyway. So how did de Villiers know all about CIA bases and Hezbollah plots? Probably because his life was one long spy story. In the 1950s, de Villiers was a reporter who almost died after a French agent in Tunisia used the unwitting journalist in an assassination scheme. The newspaperman survived, but his encounter with the world of espionage left a strong impression. Eventually, de Villiers decided to try writing fiction, and over the years, he’s injected his stories with real-life intrigue thanks to an incredible network of spies and diplomats. De Villiers rubbed elbows with African warlords, Russian agents, and the world’s most powerful politicians. He met terrorists, befriended bomb experts, and interviewed soldiers across the world. Even the character of Malko is based on three people de Villiers actually met: a French spy, a German baron, and an Austrian arms dealer. In exchange for information, de Villiers created fictional characters based on his factual sources. De Villiers traded cameos for state secrets. Spies like reading about themselves, just like everyone else.