Yet his disturbing and complex legacy goes deeper than simple theft. It involves repeated cases of mass murder unlike almost anything else the world has ever known.

10The September 30 Coup

In 1965, Indonesia was a political mess. President Sukarno had overseen crippling inflation and managed to alienate both sides in the increasingly tense Cold War. It was from these dismal circumstances that the 30 September Movement was born. In the early hours of October 1, 1965, a group of disaffected army officers kidnapped and murdered six high-ranking generals, declaring themselves in control of the armed forces. Facing a potential coup, Sukarno had no choice but to hand almost all his powers over to the loyalist military under the control of Suharto. It was the beginning of the end. Although Suharto succeeded in wiping out the 30 September Movement, he never relinquished his emergency powers, eventually using them to replace Sukarno as president. It’s now thought that the Movement may have been orchestrated from behind the scenes by Suharto himself. Whatever the truth, the misguided actions of the Movement would set Indonesia on a long and bloody course.

9The 1965 Mass Killings

With the 30 September Movement quashed, Suharto embarked on a campaign to eliminate all dissent in the country. Under the pretense of purging the Indonesian Communist Party, he sent his troops on a killing spree. For over a year, Indonesia’s intellectuals and ethnic Chinese were murdered in a massacre so bloody we still don’t know how many lives it claimed. Common estimates put the number at 500,000–1,000,000 deaths, but some have claimed it may be as high as 2.5 million. One thing all accounts agree on, though, was the campaign’s brutality. Across the nation, military units forced ordinary people to carry out the murders, including killing their own friends and relatives. In some provinces, villagers were ordered to beat hundreds of prisoners to death with crowbars. In others, violent thugs garroted thousands with wire. At the height of the violence, bodies lined every street. A stench of blood settled over towns so thickly that residents had to evacuate. Rivers clogged with discarded corpses, and still the killings continued. By the time they finally ended, there was no one left to oppose the new dictator.

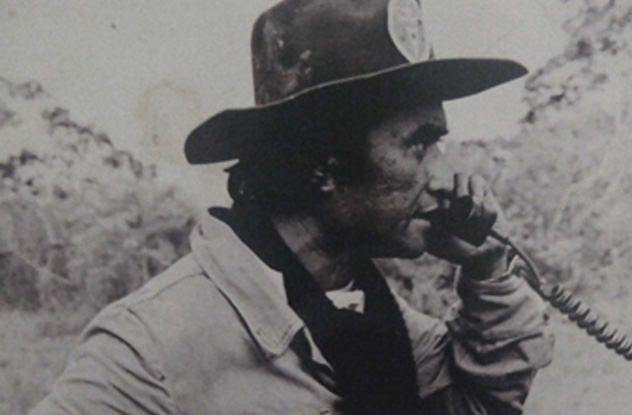

8The Fate Of West Papua

In 1963, the province of West Papua had come under unwilling Indonesian rule. By the time Suharto gained power, there was a strong demand for independence and self-determination. According to one Washington cable from the time, at least 85 percent of the population wished to secede from Indonesia. Instead, Suharto embarked on a sustained campaign to destroy their culture. After a sham vote in which only those selected by the military were allowed a say, Suharto claimed total control of the province. A brutal period of authoritarian rule followed, and all signs of Papuan nationalism were banned under penalty of a 15-year prison sentence. At the same time, a policy of transmigration was enacted, which brought so many Javanese into the province that they quickly outnumbered the natives. With their culture effectively outlawed and destroyed, West Papuans then had to watch as the regime turned their entire country into a gigantic environment-trashing mine. Today, more than a decade after Suharto was finally deposed, West Papua remains an unwilling outpost of Indonesia.

7The Genocide In East Timor

Most dictators are content with only one horrendous killing spree. Suharto managed two. In December 1975, he parachuted the first Indonesian troops onto the island of East Timor, allegedly in response to a communist threat. What followed was one of the worst massacres in history. Within 24 hours of landing, Suharto’s troops were committing atrocities. In one town, 150 civilians were picked at random, led onto a jetty, and shot into the water by a firing squad. In the capital of Dili, men and boys were targeted for mass executions. In the town of Malim Luro, soldiers forced 60 civilians to lie on the ground at gunpoint. They then drove a bulldozer over them, sprinkling a thin layer of soil over the crushed bodies. Other atrocities saw entire villages locked in buildings, which were then set on fire. Survivors of the initial invasion were left to die of starvation. All told, the occupation of East Timor resulted in over 200,000 deaths. On a per capita basis, this was the deadliest genocide of the 20th century aside from the Holocaust. At a bare minimum, one-third of all Timorese died, and the figure may have been even higher.

6A Booming Economy

Suharto’s New Order drove an economic boom almost unparalleled in modern times. When he seized power from Sukarno, around 60 percent of all Indonesians lived in poverty. By the time he left office 31 years later, that number was down to 13 percent. During his rule, Jakarta magically transformed from a sprawling mess of slums and filth into one of Asia’s slicker boom towns. What marks Suharto out from other dictators is that he made sure everyone got a piece of the pie. He built schools, roads, and health clinics in even the remotest provinces. As GDP expanded at an impressive 8 percent per year, his regime made sure nearly every Indonesian had a job and historically high wages. He saved the country from the economic meltdown Sukarno had left it in. As a result, plenty of Indonesians continue to revere him to this day.

5The Petrus Killings

Another area where Suharto had great success was in keeping down crime. But unlike his economic achievements, his crime stats came from terrible policy. Instead of jailing suspected criminals, Suharto had his men murder them. Known as the Petrus Killings, the operation aimed to strike terror into the hearts of civilians. Over a period of three years, military, police, and vigilantes on the government payroll rounded up anyone they suspected of criminal activity and executed them without trial. To make sure that other potential criminals got the message, the bodies were mutilated and dumped in public places, a handful of money left beside them to cover funeral costs. Over 2,000 people were murdered during the operation. Not all of them were criminals. Innocent civil servants and farmers are known to have been among the victims. Many suffered almost unimaginable fates, such as being forced to jump into a rocky canyon already filled with the decomposing bodies of other victims. Suharto would later boast about the operation in his autobiography.

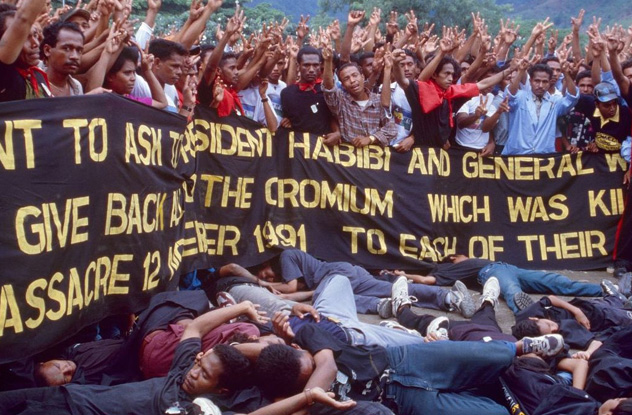

4The Santa Cruz Massacre

In 1991, peaceful protests erupted across occupied East Timor. Under the trigger-happy eye of the Indonesian military, thousands of Timorese marched to the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili to lay flowers on the graves of resistance fighters. Once the cemetery was full, the military leveled their guns and opened fire. The result was a scene from a nightmare. Hemmed in by guards and walls, the Timorese protesters had nowhere to run. As people tried to escape, the military unleashed volley after volley into the crowd until the ground was slick with blood. At least 400 protestors were seriously wounded, and 270 were killed. Many more disappeared, presumably rounded up and murdered by the military. The attack was such a bloodbath and so clearly unprovoked that the UN condemned Suharto’s government publicly for the killings. Yet it was all for nothing. To this day, no one has been held to account for the Santa Cruz Massacre.

3Economic Collapse

By the late ’90s, Suharto had transformed his economic boom into an opportunity for corruption and cronyism. Contracts, subsidies, and entire companies were handed over to family members, squeezing Indonesia’s middle class dry. Then in July 1997, the economy of Asia utterly collapsed. Currencies plummeted, countries flew toward default, and no one was safe, not even Suharto. As Indonesia plunged into an economic disaster easily as bad as the 2008 recession in the US, students took to the streets of Jakarta, demanding change. Rather than simply police the protests, Suharto sent in the army. At Trisakti University, four students were killed by gunfire. Dozens more were badly injured. For the people of Indonesia, it was the final straw.

2The Apocalyptic Riot

In response to the student killings, the whole of Jakarta went into meltdown. For two days, citizens rioted. At Plaza Klender in the city’s east, someone lit a fire in a department store full of looters. The resulting inferno killed 486 people. Across the city, shops were smashed and plundered, their owners barely escaping with their lives. In the violence that followed, gangs used the cover to attack and murder ethnic Chinese. Others stalked Jakarta’s buses, raping any Chinese women they found. The riots sealed Suharto’s fate. As the death toll climbed beyond 1,000, his supporters deserted him all across the country. Finally, 10 days after the riots first ripped Jakarta apart, the elderly dictator was forced to step down. In a brief televised ceremony, he transferred power to his deputy and bowed out of politics. Thus ended one of the longest and bloodiest dictatorships in modern history.

1A Happy Death

It would be fitting to write that Suharto died miserable, humiliated, and utterly alone, but he didn’t. As he slipped away in the early days of 2008, hundreds of Indonesian politicians came to visit the dictator and thank him for his reign. Outside the hospital, everyone from reporters to human rights activists laid flowers and prayed for his soul. In East Timor, leaders asked their people to forgive him, claiming that he had done “many positive things.” When he finally died, the government declared a week of mourning. In the years between his resignation and death, Suharto never stood trial for any of his crimes. He never paid back a penny of the billions his family stole. He remained revered, courted by his country’s politicians and international businessmen. At his funeral, politicians from around the world lined up to pay their respects. Former Australian prime minister Paul Keating even took to television to defend his legacy, claiming that the genocide in East Timor was nothing more than biased reporting. Suharto died a hero, an undeserved end for one of the 20th century’s greatest butchers.