However, there was a time when perfectly rational people not only believed in mermaids but sometimes also convinced themselves that they had seen one in the scaly flesh. Here are ten such reports.

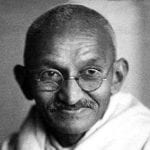

10 Christopher Columbus

In 1492, Christopher Columbus set off to find a new trade route to Asia and famously “discovered” the “New World” of the Americas by mistake. Not only did he find a new continent, but he also observed a few mythological creatures. He recorded in his journal that he was sailing in waters close to the Dominican Republic when he saw three mermaids, which he described as “not half as beautiful as they are painted” and as having “some masculine traits.”[1] It is now generally accepted that what Columbus actually saw was likely a manatee or dugong. Both creatures are able to do “tail stands,” which would lift their heads and torsos out of the water. Their forelimbs look vaguely like arms, and they are able to turn their heads from side to side. So, in the dusk, after having been at sea for six months and possibly having had too much rum, it is perhaps understandable that an experienced sailor would mistake a sea cow for a Siren. Though it must have been pretty strong rum. Columbus wasn’t alone, however. The supposed skeleton of a mermaid was presented to the Portsmouth Philosophical Society in 1826, but it turned out to be a dugong, which was no doubt disappointing, as a mermaid would have livened up their meetings considerably.

9 Taro Horiba

In 1943, at the height of World War II, a group of Japanese soldiers were stationed on one of Indonesia’s Kei Islands. They began to report seeing strange creatures in the waters around the island. The creatures were said to have a humanlike face but a mouth like a carp’s, with needle-sharp teeth. They were also about 0.9 meters (3 ft) tall, with pink skin and spikes on their heads. The creatures were seen around the edges of the many lagoons or cavorting along the beaches. If approached, they would dive into the water and not resurface. When the soldiers asked the locals about the creatures, they were told that the mermaids were known as Orang Ikan, which translates from Malay as “fish people,” and were fairly common in the area. Reportedly, local fishermen sometimes found them caught up in their nets and promised to keep one for the soldiers. Sergeant Taro Horiba claims to have been shown a creature that looked half-human/half-ape/half-fish (yes, that is three halves) and had webbed fingers and toes like some kind of amphibian. Horiba did not think to take a photo of this creature, which was unfortunate, but he did spend a great deal of time trying to persuade zoologists to investigate the creature after the war. So it must be true.[2]

8 The Chief Of A Scottish Clan

In 1830, crofters in the Outer Hebrides, off the coast of Scotland, were cutting seaweed on the shore when they spotted the figure of a small woman in the water. Some of the men tried to catch her, and as she was escaping, a boy threw a rock at her. The crofters said that they heard her cry out in pain as she disappeared beneath the waves. A few days later, her body was found washed up on the shore. Crowds gathered, and they sent for the most important person around, the chief of MacDonald of Clanranald, part of the great Scottish MacDonald Clan, who also happened to be the local sheriff. The upper half of the mermaid was said to be the size of a four-year-old child, albeit with abnormally large breasts. Her skin was soft and white, and she had long, dark hair. The lower half was like a salmon without scales. The clan chief ordered a shroud and a coffin be brought to the beach, and the mermaid was buried in the nearby churchyard. Her funeral was said to be the best-attended funeral they had ever had. Unfortunately, they didn’t think to take a collection for the headstone, and the exact location of the mermaid’s grave is unknown. This is not the only mermaid to have found its way to Scotland. In 1833, a professor of natural history at Edinburgh University reported that Scottish fishermen had captured a live mermaid and held it captive for three hours while they studied it. The creature apparently had a face like a monkey, the torso of a woman, and a tail like a dogfish.[3]

7 The Shaman Of Hakata

Japan has a long association with mermaids, although the mermaids of Japanese legend are significantly more fishlike than the buxom European ones we might be used to. They usually have razor-sharp teeth and occasionally horns as well and are said to have magic powers, though these are usually unspecified. The purported remains of one such Japanese mermaid can be seen in Fukuoka at the Ryuguji Temple. In 1222, a mermaid is said to have washed ashore at Hakata Bay. The local shaman declared that the mermaid was a good omen, and its remains were buried in the Ryuguji Temple, whose name means “the undersea palace of the dragon god.” Fitting. For many years, visitors to the temple were offered water to drink, in which the mermaid bones had been soaked. The water was said to be a prophylactic against numerous epidemics. Six of the bones still remain in the temple, rubbed smooth by their time in the water.[4] Many visitors still find their way to the mermaid’s tomb, which may or may not explain why the guardians of the temple have decided not to DNA-test the bones. Some scientists who have studied the bones, however, believe that they may well come from more than one animal and probably not from any known aquatic creature. Some scientists even believe that the mermaid’s bones may, in fact, be those of an ordinary landlubbing cow.

6 Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson was an English explorer in the early 17th century. He is best known for his explorations in North America and for the bay, strait, and river that are named in his honor. He made four expeditions looking for the fabled Northwestern Passage to the Far East. When his passage through the Arctic was blocked by ice during his second voyage, he changed course and sailed northeast toward the Russian region of Novaya Zemlya in the Arctic Ocean. Again, his passage was blocked by ice, and he was forced to retreat. While in the Russian waters, however, he had an encounter with a mermaid. Hudson described his mermaid as being, from the navel up, the size of a full-grown woman with white skin and long, black hair. “Going downe,” he saw a tail the shape of a porpoise, with a speckled Mackerel pattern.[5] Or perhaps it was a porpoise, with the tail of a porpoise.

5 Prince Shotoku

Prince Shotoku, one of the most important figures in Japanese history, was a powerful and sober man. In the seventh century, he introduced the Seventeen Article Constitution, which set the expected ethical behaviors for officials. The prince was not the kind of man to believe in fairy tales. However, a merman was said to have appeared to Prince Shotoku at Lake Biwa. The merman was dying and so, as dying people always do, found time to tell his story to a stranger. The merman said that he had once been a fisherman who had sailed into forbidden waters. As a punishment, he was turned into a hideous, fishy creature. The merman, or ningyo, clearly felt that this was a just punishment because he asked the prince to build a temple to display his body after his death, as a warning to other fishermen to stay inside the lines. This temple, known as the Tenshou-Kyousha Shrine, can be found near Mount Fiji, where the mummified remains of the mermaid are watched over by Shinto Buddhist monks.[6]

4 Captain Richard Whitbourne

Richard Whitbourne was an explorer, writer, and colonizer of other people’s land in the 16th and 17th centuries. He led ships in battle against the Spanish Armada and organized the supply of fish from Newfoundland to the Mediterranean. So, he was a man of wide experience, one might think—not one for fanciful imaginings. In 1610, off the coast of Newfoundland, he described his encounter with a mermaid that swam “cheerfully” toward the small boats he and his crew were sailing offshore. He stated that the mermaid swam swiftly, diving under the water at times and then rising out of the water high enough for him to “behold” her bare shoulders and back. He claims not to have looked at the front of her. Whitbourne described how she came up to their boat and tried to climb in, but the sailors were afraid, and one of them hit her over the head with his oar, whereupon she let go and swam toward another boat. All the men, then, being frightened, made for the shore as quickly as they could.[7] Whitbourne’s account appears to be very detailed and is written in his usual neat handwriting, which must have been particularly difficult after all that rum.

3 Captain John Smith

The explorer Captain John Smith may or may not have rescued/been rescued by Pocahontas (not). He was elected leader of the Jamestown colony and traded largely peacefully with the Native American Powhatan tribes around them. He seemed to be a levelheaded kind of guy. Thomas Jefferson once described him as “honest, sensible, and well informed.” Surely, then, his account of seeing a mermaid can be taken at face value? It is claimed that in 1614, he saw a green-haired woman, “by no means unattractive,” swimming in the water. When she turned to dive, Smith was apparently shocked to see her mermaid’s tail. Manatees are often sighted in the bay where Smith had his Sirenian encounter, so it may be tempting to believe that he, like others, saw the manatee from behind and thought he had seen a mermaid. However, it has been suggested that not only might Smith have not seen a mermaid, but he might not even have claimed to have seen a mermaid. Some scholars believe that the account of the mermaid sighting was written not by John Smith but by Alexander Dumas, author of such novels as The Three Musketeers and The Man in the Iron Mask. The account was purportedly written contemporaneously by Smith in 1614, whereas, in fact, Smith had not been in that area since 1607. No evidence of the mermaid entry can be found in Smith’s original notes, most of which are still available. The first mention of Smith’s encounter with a mermaid is in a tale by Dumas, in which he cited Smith’s account. Smith’s supposed adventure lent credence to Dumas’ own story about a man who sired four children with a mermaid.[8]

2 Blackbeard

Edward Teach, the legendary pirate known as Blackbeard, served first as a privateer during Queen Anne’s War. He became a pirate after the war ended. He named his ship the Queen Anne’s Revenge in honor of his former employer. Blackbeard and his crew cruised the Caribbean, plundering ships and adding them to their fleet. His pirate crew of 300 was the largest ever to trouble shipping on the high seas. At one point, he brazenly blockaded the port of Charlestown, seizing any ships that attempted to enter or leave and demanding ransoms for the release of captured sailors. In 1718, the Queen Anne’s Revenge was run aground. Some scholars maintain that Edward Teach deliberately scuppered his own ship in order to break up the crew, who were fast becoming a liability. Blackbeard was soon caught and killed, and his severed head was mounted at the front of his captor’s ship as a warning to others. Before he met his grisly end, however, Blackbeard had an encounter that was altogether more ethereal. It is recorded in his logbooks that he ordered his crew to steer away from certain “enchanted” waters because they were populated by merfolk. He was said to have seen the merfolk with his own eyes and to have been wary of vexing them.[9]

1 Henry Loucks

Henry Loucks was a fisherman working the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. He was said to have been “as reliable as any fisherman on the river,” which may or may not be a testimonial. In 1881, Loucks reported five separate sightings of a mermaid on the Susquehanna River. He claimed that the mermaid came out at sunrise and at dusk, rising to the surface of the water, whereupon it had a good look around, floated on top of the water for a while, and then slowly sank beneath the surface, leaving its hair floating on the surface for a moment before finally diving to the depths below. Loucks said that he had considered shooting it but was worried about being charged with murder, so he let it go. When asked if, as in the fairy tales, the mermaid carried a comb and a mirror, he replied, “It might have had, but I didn’t see it.” When asked where he thought it went, he supposed that it had a cave somewhere at the bottom of the river. Newspaper reports appealed for the mermaid to be captured, alive if possible, and reassured potential mermaid hunters that they would be immune from prosecution if they brought it in dead. To date, no one has taken advantage of the offer.[10] Ward Hazell is a writer who travels, and an occasional travel writer.