Today, we have very sanitized images of striking workers—folks walking in circles with picket signs while chanting catchy slogans about unfair labor practices. Perhaps after a few days of interrupted business, workers and their bosses will sit down and work out some compromises. For most of American history, going on strike meant something far more radical. It was an indictment not only of individual work sites but also of a social order in which few were rich and most were desperately poor. Going on strike could—and often did—mean being beaten by strikebreakers, being shot at by National Guardsmen, or even having bombs dropped on you from biplanes.

10 The Great Railroad Strike

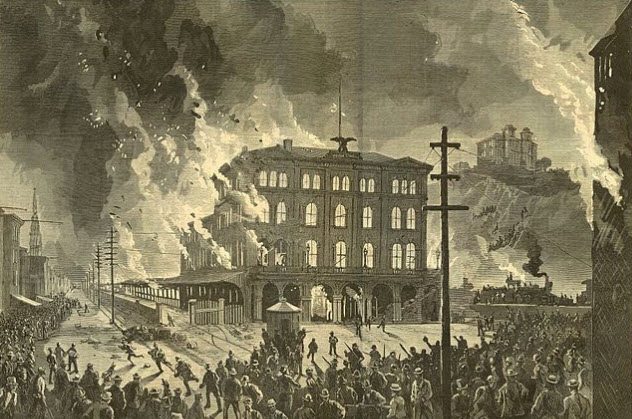

On July 14, 1877, railway workers in Martinsburg, Virginia, went on strike to protest the third pay cut within a year. Workers disrupted rail operations and prevented all train traffic. The strike soon spread to Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Missouri. It was the first national strike in US history. Within six days, first blood was drawn when Maryland National Guard troops confronted striking workers in Baltimore and opened fire on them—killing 11 and wounding 40.[1] Over the following two days, Pennsylvania National Guard troops killed 40 striking workers in Pittsburgh, firing upon crowds and bayoneting the strikers. At the same time, federal troops killed as many as 18 striking workers on the streets of St. Louis. This violence proliferated. As many as 44 strikers were killed in Pennsylvania, 30 in Chicago, and eight in New York. By the end of the strike, more than 100 workers had been killed by cops, National Guard troops, and federal soldiers. In the aftermath of the widespread violence and destruction, both workers and state governments took the events as a sign of a great struggle to come. State governments began growing their National Guard regiments, while labor unions ramped up recruitment and organizing efforts. It would be nearly a century before the bloody contest would come to an end.

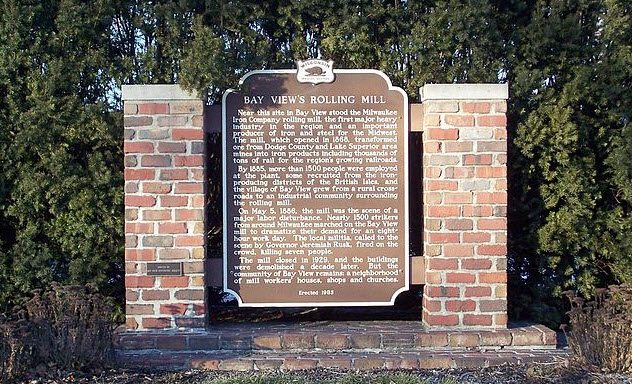

9 Bay View Massacre

On May 1, 1886, over 200,000 working-class men and women kicked off a nationwide campaign to win a nationally recognized and enforced eight-hour workday. In Milwaukee, such efforts led to the mobilization of 12,000 workers. By May 3, the striking workers had managed to shut down every factory in Milwaukee with the exception of the North Chicago Railroad Rolling Mills Steel Foundry in Bay View. Fifteen hundred strikers mobilized to march upon the mills and encourage the workers to join the strike.[2] Meanwhile, Milwaukee business owners were growing understandably anxious. Since day one of the strike, they had been pressuring Wisconsin Governor Jeremiah Rusk to call in National Guard troops to end the strike. For three days, Rusk resisted the employers’ demands. However, by the morning of May 4, several companies of the local Guardsmen had arrived at the mill, 250 men in total. On May 4, the situation grew tense as striking workers hurled rocks and insults at the National Guardsmen. In response, the soldiers fired rounds above the workers’ heads. By this point, the pressure on Rusk had reached a breaking point. That night, he ordered Captain Treaumer, who commanded the National Guard companies, to shoot at any striking worker who attempted to enter the mill. On May 5, the striking workers again assembled, chanting for an eight-hour workday. They were approaching the line of National Guardsmen when Treaumer gave the order to begin firing upon the crowd of workers. The volley killed 15, including a retired bystander and a 13-year-old schoolboy who had excitedly joined the crowd. The violence had the intended effect of breaking the strike. As a result, it would be many years before the common implementation of the eight-hour day.

8 Morewood Massacre

On February 2, 1891, more than 10,000 coke oven operators and miners halted all work in the expansive coke fields of Morewood, Pennsylvania. Organized by the United Mine Workers union, the workers demanded better wages and an eight-hour day. Negotiations between the striking workers and US industrialist Henry Clay Frick continued through the rest of February and into March. The strike nearly ended on March 26 when talks neared a wage agreement. The negotiations did not pan out. On March 30, over 1,000 striking workers damaged company property, destroying coke ovens and damaging railway lines in Morewood. In response, Pennsylvania Governor Robert E. Pattison ordered in local National Guard troops. As striking workers began mobilizing again on April 2, the troops opened fire on the unarmed workers. Seven men were killed. When this did not stop the strikes, Frick called upon 100 strikebreakers to regularly attack and harass the strikers. By May, the strike broke and the beaten, bloodied workers returned to the coke mines and furnaces.[3] Three years later, conditions had not improved. Matthew J. Welsh, a worker in the coke fields, sent the following letter to the Pittsburgh Times, which was published on April 14, 1894: The workingmen, and especially the Hungarians, of the coke region are represented as an ignorant class of men. Certainly we are to a certain extent or we would not be toiling our lives out with work that former day slaves never dreamed of on a coke yard or in the mines. Ignorant as we are, we know that it is time to quit work and die of starvation rather than be trying to work and starving at the same time.

7 Pullman Strike

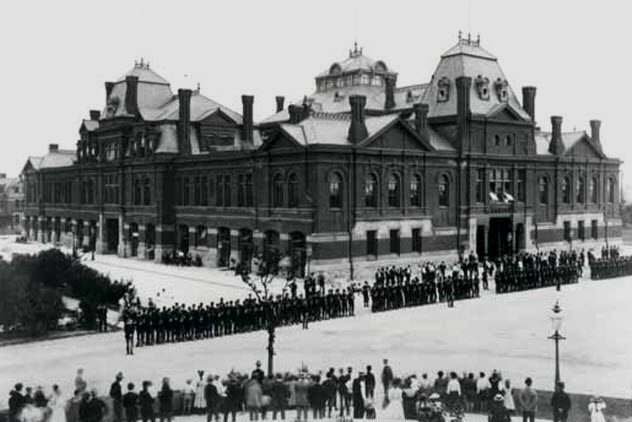

On May 11, 1894, the recently formed American Railway Union went on strike against the Pullman Company in Chicago, Illinois. The workers sought union recognition, a key step in securing fair wages and working hours. Like the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, railroad workers across the country went on strike, partly in solidarity, partly to win an improvement of their own working conditions. At its zenith, more than 250,000 workers were striking across 27 states, bringing railroad traffic in much of the nation to a grinding halt and disrupting every major industry. This put enormous pressure on local, state, and even the federal government to end the strike swiftly—and brutally, if needed. In June, President Grover Cleveland mobilized a massive force of thousands of US Marshals as well as 12,000 US Army troops. These marshals and soldiers deployed across Nebraska, Iowa, Colorado, Oklahoma, California, and Illinois. Troop responses to the striking workers varied, narrowly avoiding violent clashes in some regions such as Sacramento while killing more than a dozen strikers in Chicago, the heart of the strike. In total, more than 30 workers were gunned down by state and federal troops. Many more were wounded.[4]

6 Lattimer Massacre

In August 1897, the Lehigh and Wilkes-Barre Coal Company laid off coal miners from the Lattimer mine near Hazleton, Pennsylvania. Those who remained faced wage cuts, increased rent for living on company properties, and cost cutting measures that meant longer hours and increasingly dangerous working conditions. Such conditions gave rise to a strike. The workforce consisted largely of immigrant workers, primarily of Polish, Slovak, Lithuanian, and German origin. By September, as many as 10,000 workers were on strike. Initially, they were successful in negotiating higher wages. But the company broke the promise, prompting further outrage among the strikers. By this point, the mine owners, growing increasingly frustrated at the loss of revenue and their inability to dupe workers back into the mines, called upon local Sheriff James L. Martin to disperse the strike. Initially hesitant, Sheriff Martin organized a posse on September 10 to confront some 300–400 (mostly Slavic and German) unarmed strikers in Lattimer who were on their way to support the unionizing efforts of other local coal miners. When the sheriff’s demands to disperse were repeatedly ignored, one of his men shouted, “Shoot the sons of bitches.” The posse opened fire on the peaceful, unarmed crowd. Nineteen men were killed, and many were shot in the back.[5] The nation immediately understood that this massacre was different. In previous strikebreaking efforts, law enforcement could at least attempt to justify their violence by pointing to the aggression and unarmed violence of striking workers. However, in Lattimer, the strikers were simply walking by. A monument to the slain workers in Lattimer reads: It was not a battle because they were not aggressive, nor were they defensive because they had no weapons of any kind and were simply shot down like so many worthless objects, each of the licensed life-takers trying to outdo the others in the butchery.

5 Chicago Teamsters’ Strike

In April 1905, workers at the Montgomery Ward department store went on strike in Chicago, Illinois. Their chief complaint was that the owner subcontracted to nonunion workers. This minor labor dispute rapidly grew when the Teamsters Union launched strikes in solidarity with the department store workers.[6] The Teamsters had a strong Chicago membership. About 30,000 out of its 45,000 total members were in the Windy City. Soon, nearly every major employer in the metropolitan area of Chicago was affected. In response, the Employers’ Association of Chicago raised millions of dollars (adjusted for inflation) to hire a massive force of strikebreakers. These men received special protections from the courts, allowing them great leniency in dishing out violence. The Teamsters and other union strikers often clashed with the strikebreakers. By the time the strike ended in August, more than 20 striking workers had been killed in clashes with strikebreakers (none of whom were killed). More than 400 workers were also injured.

4 Paint Creek–Cabin Creek Strike

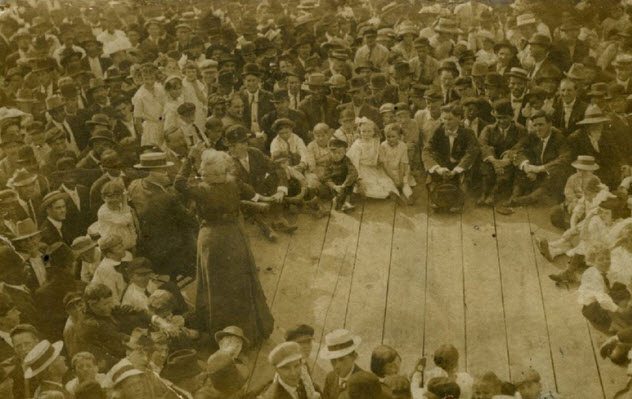

On April 18, 1912, West Virginia coal miners at Cabin Creek, under the banner of the United Mine Workers, went on strike. Among their demands were union recognition, better wages, and improved working conditions. Shortly afterward, nearby miners at Paint Creek joined in. Tensions escalated when the mine owners hired the infamous Baldwin–Felts Detective Agency to end the strike.[7] Little more than a gang of thugs, the strikebreakers harassed the striking miners for months, often sabotaging their food, beating them, and even shooting at them from afar. By September, after months of standoff, thousands of coal miners from neighboring regions of West Virginia were moving to join the existing strikers. While skirmishes were frequent, progress toward any resolution was not. Months passed. Frustrated by the impasse and the enormous loss of revenue, mine owners encouraged local law enforcement to increase their violence against the striking workers. In February 1913, 10 months into the standoff, Kanawha County Sheriff Bonner Hill and a group of detectives resorted to truly desperate and brutal measures of repression. They brought in a heavily armored, weaponized train and assaulted the strikers’ camp with high-powered rifles and machine guns, deliberately targeting the homes of strike leaders. The vulgar display of violence demoralized the strikers. But they continued to resist for another five months until the strike was completely broken in July 1913. Over the course of the 15-month strike, more than 50 workers were killed and many more were wounded. It is also estimated that many died from starvation, disease, and related causes due to the conditions of the strikers’ camp.

3 Ludlow Massacre

In September 1913, approximately 12,000 coal miners in Ludlow, Colorado, went on strike to protest low wages and unsafe working conditions. Colorado was the deadliest state for coal miners, with a death rate about twice the national average. The strike had been organized with the help of the United Mine Workers. Along with their other demands, the workers sought union recognition because unionized mines had 40 percent fewer workplace deaths. Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, which owned and operated the coal mines, began evicting striking workers and their families from the company towns in which they lived. The workers moved with their families into a nearby tent colony that they had set up in anticipation of such an event. The mine owners hired the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency—little more than a private gang of armed thugs—to break the strike. For months, the “detectives” harassed the strikers in their camp. At night, the thugs would shine floodlights into the camp, sometimes firing randomly at tents and occasionally maiming and even killing workers.[8] In October 1913, after a bloody month of violence, Colorado Governor Elias M. Ammons ordered the National Guard to move into the area. The miners had initially hoped that the arrival of the militiamen would bring peace and end the violent attacks they endured daily at the hands of the strikebreakers. This proved little more than wishful thinking as the sympathies of the soldiers became clear. They palled around with the strikebreakers, and the two forces became nearly indistinguishable. Six months passed. Progress toward any resolution was nonexistent. Unable to tolerate the strikers’ colony any longer, the mine owners urged the strikebreakers and militiamen to take drastic measures. So on the morning of April 20, 1914, as 1,000 men, women, and children were getting ready for their day, machine gun fire ripped through the camp. The volley left 13 immediately dead. The leader of the strike was lured out of the camp to “negotiate a truce,” but he was executed instead by National Guard troops. That evening, the militiamen and strikebreakers moved into the camp, setting fire to it. By the following day, the camp was mostly abandoned. One worker picking his way through the camp uncovered the burned corpses of two women and 11 children. The massacre sparked national outrage. In Denver, the United Mine Workers prepared for war. Hundreds of armed strikers from nearby striker colonies marched to the Ludlow region. Thus began the Colorado Coalfield Wars, a brutal period of widespread armed conflict between workers and National Guard troops in the state. Although the period of intense conflict ended by the beginning of May, the strike would continue until December. It ended in defeat for the workers. By the end of the conflict, nearly 200 people had died.

2 The Battle Of Blair Mountain

In May 1920, agents of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency went to Logan County, West Virginia, at the behest of local mine owner-operators to prevent efforts by miners to form a union. Upon arrival, the agents began evicting the families of miners suspected of unionization efforts. As the Baldwin-Felts men worked their way through the town of Matewan, locals began to take notice, along with the mayor and Police Chief Sid Hatfield. Numerous armed miners had also arrived. The ensuing confrontation erupted into gunfire, leaving two miners, the mayor, and seven Baldwin-Felts agents dead. Sid Hatfield became a local hero to the working people. For the next 15 months, a protracted labor dispute carried on. Miners sabotaged equipment and went on strike, while mine owners continued to fire workers, evict them, and bring in new workers. The extended dispute took a dramatic turn when Sid Hatfield was murdered by the brother of two Baldwin-Felts agents who had been slain in Matewan. Miners all across the region began pouring out of the mountains to join forces and take up arms, intent on ending the tyranny of mine owners and their hired guns. As many as 13,000 miners marched on Logan and Mingo Counties to unite many more thousands of miners, drive out the hired gunmen who constantly terrorized them, and unionize the southern counties of West Virginia. It was the largest armed insurrection since the US Civil War. Meanwhile, Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin—securely in the pocket of the regional coal mine owners—was given sizable funds to put together a private military force to stop the workers’ march. Chafin and his men set up on Blair Mountain, a daunting natural obstacle which lay in the strikers’ path. The first skirmishes broke out between strikers and hired goons on August 20, 1921. A brief agreement to cease the march came to a quick end when Chafin, displeased at letting his assembled force go to waste, murdered several union sympathizers in a nearby town. Infuriated, the strikers continued their siege of Blair Mountain. Chafin employed pilots to drop surplus munitions (bombs and gas) left over from World War I onto the workers. President Warren Harding ordered federal troops to move into the area and even threatened to deploy Martin MB-1 bombers against the striking workers.[9] Instead, under the command of General Billy Mitchell, the planes were used to run reconnaissance. The troops arrived on September 2. Fearing a bloodbath, strike leaders disbanded the march. As many as 100 strikers were killed during the conflict.

1 Memorial Day Massacre

On May 26, 1937, Cleveland steelworkers went on strike when minor steel companies refused to follow the US Steel Corporation in adopting union demands of recognition, eight-hour workdays, and better pay. The work stoppage in Cleveland led to calls for strikes by two major unions—the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO)—which took place in many cities across the country. On May 30, the Memorial Day holiday, approximately 1,500 striking steelworkers and allies in Chicago assembled at the SWOC headquarters. They planned to march to the nonunionized Republic Steel mill nearby in protest. At the gates of the mill, the unarmed, peaceful crowd—which included women and children—was met by 250 armed Chicago policemen, who were provisioned and paid for by Republic Steel. Without provocation, the assembled policemen fired over 100 shots at the crowd, killing 10 and wounding more than 100. Most were shot in the back.[10] Not one officer was indicted for the shooting. Centered in Cleveland, the strike was gradually defeated, with Chicago being the only violent incident during the entire work stoppage. However, the massacre of Chicago workers and the strike brought national attention to the plight of the steelworkers. Five years later, they won union recognition and the fulfillment of their demands. Zachary is a graduate student in history in Arizona. His work focuses on the struggle of the American working class and labor movement. He runs the American Labor History Facebook page.