10 Jane McCrea

Born in 1751 and killed in 1777, Jane McCrea has a strange story that exists somewhere between fact and fiction. According to the popular story, McCrea was visiting with friends when she found herself and her companions surrounded by Native Americans who were allied with the British. McCrea was ultimately killed and scalped, and because the general in charge of relations with the tribes was afraid of the fallout should he avenge her death, he let her killers go. According to the Native Americans, on the other hand, McCrea had been accidentally killed by an American musket ball. Once the locals heard the news, they quickly took up arms with the group of rebels who were marching against the British forces that had let one of their own be brutally murdered. McCrea’s death is noted as a moment in the war when sides were chosen. Historians are unsure how much of the story is true and, for that matter, who Jane McCrea really was. Because she’s become a legendary figure, the story is changed with each retelling. She’s become much more beautiful as time goes on. She was also purportedly engaged—in later versions of the tale—to a young soldier who finds out about her grisly fate when he recognizes the trophy that is her scalp. Supposedly, she was killed beneath a tree, which was allegedly later used for making McCrea souvenirs. There’s a house with her name attached to it, but there’s no evidence that she ever lived there. Whatever the truth really was, the sensationalized stories spread like crazy through the newspapers of the colonies. Readers were enraged by how the British soldiers cared more for their relationship with the so-called savages who would kill and scalp an innocent young girl, and the images created of McCrea went a long way in forming attitudes not only toward Native Americans, but toward the British as well. McCrea’s body has been exhumed several times, most recently in 2003. The forensic investigation found that her bones bore no evidence of injury, but her skull was completely missing and likely stolen as a souvenir in the 1850s.

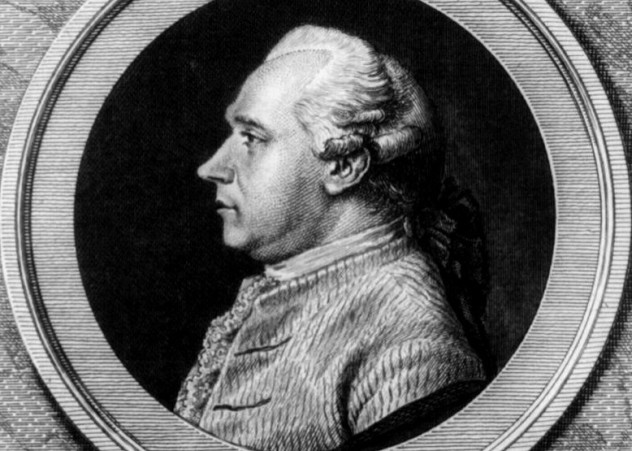

9 General Charles Lee

Charles Lee was a former member of the British Army who moved to the colonies and transferred to the Continental Army in 1775. It was a huge promotion for him, and he only had one senior officer in his new military—George Washington. Just how loyal he was to his new cause has long been up for debate, though, and it’s not clear exactly what sort of damage he did to the rebel cause. During the last years of the war, Lee was respected for his capabilities as a military leader, his decisions on the battlefield, and his devotion to the cause. Originally, no one questioned his former British allegiance—he wasn’t the only formerly British soldier on the field by any means. In December 1776, he was captured by the British. He spent the next two years a British prisoner. The events of this time are unknown, but there are plenty of rumors. According to the British General Howe, Lee spilled the beans on Washington’s strategies and told his adversaries just where to find all of the Americans’ weak spots. Documents substantiating his treason were kept quiet for a long time; they came into the public eye almost 70 years after the fact. Whether or not Lee was actually betraying his commander is unclear. Some theorize that he was feeding false information to the British. Events after his rescue in April 1778 make the object of his loyalty even less clear. With the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse descending into complete chaos, Washington and his army stepped into the battle just as Lee was leaving it. Harsh words were exchanged, leading to Lee’s suspension from his post. It’s absolutely not clear whether or not he had made the right call—as some insist that he did—and why on Earth he thought talking back to George Washington was the best course of action. He was permanently removed from the military and died two years later, leaving behind unanswerable questions about whether he was a traitor or a hero.

8 Agent 726 And The Royal Gazette

On the surface, the story seems pretty clear-cut. James Rivington was a printer living in the colonies. In 1773, he announced that he was going to publish a weekly newspaper with the goal of bringing the colonists all the news that they would possibly need to know. He originally called it Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, but it wasn’t long before it had become Rivington’s New York Loyal Gazette—with British coat of arms right on the masthead. Unsurprisingly, he was harassed, forced to flee the area more than once aboard British ships, and even hanged in effigy by an angry mob. The paper changed its name to the Royal Gazette in 1777, but when it finally came time to close the paper for the last time, he did it under a colonial guard with colonial protection. In 1783, the paper, run by one of the most hated men in all the colonies, closed. Rumors circulated that Rivington had actually been working as a double agent. Some claimed that secret messages were passed through the paper and that spies would purchase the paper and take it—and its secret messages—directly to George Washington. Evidence is circumstantial, but there’s so much of it that it seems unlikely that there’s absolutely nothing to the rumor. One of the most interesting and controversial documents is a codebook that revealed the names of all the agents working for the rebels, their code names, and a number. Rivington is given a number—726—but no aliases; it’s been argued that it simply meant he was a person of interest, not necessarily a spy. Stories told by Martha Washington’s grandson also suggest that the Loyalist printer was actually a double agent, but critics point out that the man was fond of telling tall tales, especially if he thought there was money in it for him. There are stories of Rivington meeting with Washington in New York in 1783, and even though the story is told and retold by a handful of different sources, it’s not clear if it was the truth or just another product of the rumor mill. Other evidence includes Rivington’s coffee house, which was a favorite hangout for British officers but was also financed by money coming from the known spy network.

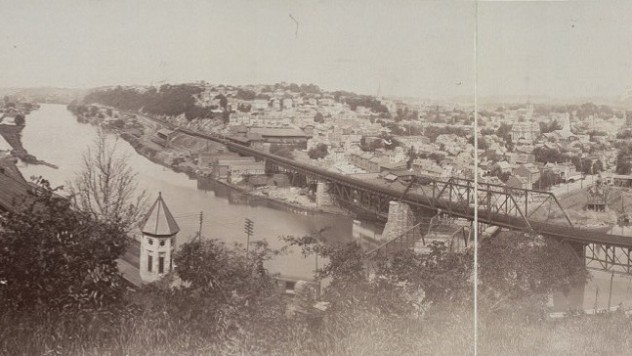

7 Easton Hospital Mass Graves

Easton, Pennsylvania was a small town with no more than 500 residents, but its value was in its location. Easton was one of the few places people could cross the Delaware River from Pennsylvania to New Jersey. In addition to being a weapons and ammunition stronghold, there was also a hospital there throughout the Revolution. Countless people were treated—or died—in the small town, but historians have no way of knowing exactly how many. Various documents recount massive numbers of troops moving through Easton, and there are many more records of sick and wounded soldiers being treated there. The hospital records themselves are mostly missing. Records from other area hospitals and trends throughout the area have suggested that Easton probably saw the same high casualty rates during the cold winter months that all the other hospitals did. The sporadic records we do have from Easton indicate that the hospital was full of sick and injured soldiers. At the same time, they also housed prisoners of war who were too exhausted to be bothered to try to cause trouble or escape. Letters talk about the unsanitary, unhealthy conditions at the hospital, and there’s no way to tell how many people died there throughout the course of the war. Based on all the evidence we do have, we can safely assume that hundreds of people died in the hospital and were probably buried nearby. Whether in a mass grave or in a more formal cemetery, there have been no markers or records found. The town slowly grew after the war, but graves were never found.

6 The Wreck Of The HMS Hussar

According to the story, a nearly priceless treasure is sitting at the bottom of New York City’s East River, covered by less than 30 meters (100 ft) of water. In 1780, the HMS Hussar headed into port carrying the payroll for British troops stationed in the city. The ship never made it, though, and rather than going out in a blaze of glory, it had the rather inglorious end of hitting a sunken rock that ripped a hole in its hull and sent it to the bottom of the river. The ship was also carrying a handful of prisoners of war who were to be traded for the freedom of some British prisoners, but it’s the chests of gold and silver that have had treasure hunters searching for more than 200 years. Nothing has ever been recovered. The ship sank near Hell’s Gate, badly injured by an underwater formation called Pot Rock. Accounts say that the ship sank incredibly quickly, and even though there were attempts to retrieve the payroll almost immediately, the water was too dangerous. Other attempts were made as early as 1819. Pieces of the ship have been recovered and the site of the wreck is confirmed, but the treasure hasn’t been found. The mystery is far from forgotten, too. In 2013, Hurricane Sandy swept through the area and revealed part of what might have been a shipwreck from the era. That wasn’t the first time divers have taken to the waters with modern technology to try to find the remains of the old ship, either. Expeditions were mounted in the 1980s, and even though divers were so confident that they would find the the treasure that they brought champagne along, they never actually succeeded.

5 Valley Forge

The events of Valley Forge form one of the most long-lasting images we have of the American Revolution. American troops—mostly of civilians with little training or experience—freezing in the long winter months, wearing nothing but rags, and slowly starving. Countless people died while waiting to fight for their freedom. There’s even a monument there, established by the Daughters of the Revolution in remembrance of all the people who died and were buried there. Only now, no one’s sure that anyone’s actually buried there, and there aren’t any records of anyone starving or freezing, either. Most of the stories about Valley Forge can only be traced back to the 19th century, and many of those were based on stories that had been passed down through families rather than on actual written records from the time. In the 1970s, the National Park Service oversaw an extensive archaeological dig at Valley Forge. They found plenty of everyday artifacts, but what they didn’t find was a graveyard. There were bones found, but they were the bones of fish, horses, and cattle—animals that had both died of natural causes and that had been slaughtered for food, matching written descriptions of the conditions at the camps. Surveys of the park had specified up to 15 places that were marked specifically as human burial sites, but no actual evidence has ever been found to support the idea. When historians looked back at what we really do know about Valley Forge, it wasn’t as bad as we tend to think. Sure, there was a lot of hunger and a lack of supplies, but the troops were considerably better outfitted and more experienced than we’re taught in school.

4 Philadelphia’s Unknown Soldier

Philadelphia’s Washington Square is the home of the Tomb of the Unknown Solider. While it’s pretty obvious why this one is a mystery, it’s a fascinating history nonetheless. The area where the monument now stands has a long history with the unknown and long-forgotten dead. Before it was turned into a park, it was a potter’s field, a place where the forgotten would be buried. It was unconsecrated ground, too, and one family that’s buried there, the Carpenter family, chose to do so because it was the only place they could bury one of their own, who had committed suicide. It was John Adams who was overcome by this sense of absolute despondency while walking through the area. At the time of the war, it saw countless deaths from battle injuries and the ravages of illness and disease. Area hospitals weren’t able to cope with all the injured, ill, and dying, so camps sprang up all around Philadelphia. People died in the camps and were buried in the camps. The land was used as a mass burial plot again in 1793, after yellow fever swept through the population. In the beginning of the 19th century, it was turned into the park that stands today. After another century or so, a memorial honoring the man who led the troops was erected, as was another for the ordinary soldiers who had died in the Philadelphia field. It wasn’t until 1954 that archaeologists started digging for their unknown body. They uncovered a series of graves before they found one of the mass graves they were looking for. Based on the area around their body, the age of the boy (about 20), and his cause of death (a head wound probably made by a musket shot), they’re pretty sure he’s a Revolutionary War veteran. Which side he fought for is anyone’s guess, as colonist and British soldier alike died side by side on the old cemetery grounds.

3 The Unsolved Death Of The Colonies’ Foreign Secret Agent

A degree from Yale, a successful law practice, and two marriages to wealthy widows left Silas Deane in fairly high standing. Serving in the Continental Congress, he rubbed elbows with all the important figures, from George Washington to Benjamin Franklin. After leaving the Continental Congress, he was given a new role—Secret Agent of the Colonies. His mission was simply to head to Europe and recruit help from France, one of Britain’s biggest enemies. And he did. In the late 1770s, Deane requisitioned one of his greatest assets, the Marquis de Lafayette, signed on thousands of soldiers, and requisitioned countless shiploads of goods and supplies and even more shiploads of weapons and ammunition. With the arrival of supplies in Saratoga in time to see victory at Fort Ticonderoga, France officially declared their role in the war. Deane’s mission should have been a major success. Only, not quite. It wasn’t long after he had presented himself to France’s king that things started to go sideways for him. He was summoned back to Philadelphia in order to face questions about his finances and his spending while he was in Europe. Accused of all sorts of shady dealings, Deane argued his case for more than a year before he was finally sent away with his reputation destroyed. He had made enemies while he was in France, and those enemies were in a position to have the ear of the same people that Deane answered to. Distraught and in ruins, Deane published a paper that encouraged a reunion with England, which spelled the end of his career. He left for England in an attempt to sort out at least some of his affairs and, from there, the story gets a little more shady. After six years living in England and traveling the country, he attempted to return home with the help of some friends. He never made it. Deane died onboard the ship the day it left for America. Some speculate that he was murdered before he could return to the country he had done so much to help.

2 Agent 355

The Culper Ring was the name given to the network of spies that the colonists had working throughout the American Revolution. In the same book that named James Rivington as Agent 726, there was another mysterious designation—this one female. In all the documents in which she’s mentioned, she’s called Agent 355. She operated in New York and was instrumental in some key moments of the war. This undercover operative exposed Benedict Arnold’s treasonous actions, and caused the arrest and eventual execution of British spy Major John Andre. Because she had access to influential people, it’s been suggested that she may have been the daughter of a Tory family, secretly recruited to the colonial cause. Information that she gathered on British activities went straight through to George Washington himself, but we don’t know what her name really was. We do know—we think—that she was romantically attached to another Culper Ring member, Robert Townsend. When Agent 355 was captured in 1780 and taken to the prison ship Jersey, she gave birth to a boy she named Robert Townsend Jr. She died soon after the birth, and for the next two centuries, her identity has remained anonymous. Her contributions, though, are the stuff of Culper Ring legend.

1 Did Washington Know About The Grave Robbers?

At the time of the American Revolution, there was another revolution just getting up and underway—a medical one. Grave robbers and body snatchers had already begun to supply medical universities with fresh corpses to dissect and examine, and there are records of the same thing being done on Washington’s battlefield. After all, there were many casualties of the American Revolution. In 1775, Washington issued a decree that the robbing of his soldiers’ graves would not be tolerated. The directive came on the heels of complaints about the disappearance of a body taken from a newly dug grave. Mention of the incident also comes in the journal of a surgeon from a nearby Continental Army hospital. The mention was such that it was pretty likely that the surgeon had something to do with the body in one way or the other. A colleague of his also made mention of the chances for medical advancement that war provided—namely, the chance for what was called “anatomical investigations.” The doctor in question, John Warren, is profiled in several biographies, including those written by his sons. They wrote about the number of people who died on the battlefield with no relations left to care about their proper burial and also suggested that the disappearance of the body that got Washington’s attention was far from an isolated incident. It’s not known what kind of attitude Washington had toward the use of fallen soldiers as cadavers, although it’s definitely suggested that he knew everything that was going on in his camps. At the time, body snatching was an up-and-coming business. John Revere, son of Paul Revere, was later recruited by the Warren family to help ensure that their students of anatomy wouldn’t go without fresh bodies. Read More: Twitter