Amid the sound and the fury from the media, hard facts can be hard to come by. But look closely and you’ll find there are some inarguable truths about Europe’s current crisis.

10It’s Closer To A Refugee Crisis

Most of the press has so far characterized the crisis as being about “migrants.” The UN disagrees. On July 1, 2015, they released a statement on their investigations into the 137,000 people who had, by that point, crossed the Mediterranean this year. They concluded that the vast majority of them would be better classified as “refugees.” This has sparked an important (and emotional) debate in Europe’s media. Outlets like the BBC have chosen to keep using the term “migrant” as it is technically correct, arguing that it is neutral and accurately describes both the refugee majority and the economic migrants arriving with them. Others strongly disagree. Because “migrant” denotes voluntary action, the UN has suggested that it shouldn’t be used where the refugees are concerned. Al-Jazeera has argued that the term is used as an insult these days and dehumanizes both groups. The UK’s Channel 4 and The Guardian agree, and The Washington Post has expressed similar reservations. This is important because the language surrounding migrants has become toxic in recent weeks. UK tabloids have reported on “swarms” or “hordes” of “marauding” migrants preparing an “invasion.” One prominent columnist even called those dying in the Mediterranean “cockroaches.” It is unlikely that such things would be written about refugees, especially considering where most of them have come from.

9Most Of Those Refugees Come From The Worst Places On Earth

Of course, there are still economic migrants coming into Europe, often through the same routes. However, the majority are fleeing some of the most dangerous countries on Earth. Of those crossing the Mediterranean, one-third are escaping the carnage that is Syria. The second- and third-largest groups are coming from Afghanistan and Eritrea, the former a corrupt warzone and the latter a brutal dictatorship known as “Africa’s North Korea.” Smaller groups are also fleeing equally horrendous places. Iraqis, Somalis, and Nigerians are all making their way to the safety of Europe, as are citizens of Darfur, where genocide has been underway since 2003. Altogether, they are thought to make up 70 percent of those crossing from Africa. On the other hand, there are still large numbers coming from countries that we would not consider dangerous. In the first three months of 2015, there were more asylum applications from citizens of Kosovo than anywhere else. Albanians and Serbians also made up a significant number of the total. By and large, people from these countries have been denied asylum. Germany has made a point of turning back anyone from the Balkans.

8There Are Fewer Refugees Than You Think

At the beginning of this article, we mentioned that 350,000 people had crossed into the EU for the eight months ending in August 2015. This is 70,000 more than arrived in the whole of 2014. It’s more than the entire population of Iceland. It’s also not as big as it seems. Watch this video on YouTube As a single entity, the EU has a population of 503 million and a surface area of 4.4 million square kilometers (1.7 million mi2), larger than India and Peru combined. At that scale, 350,000 people account for less than 0.7 percent of the entire population. Although 350,000 is likely too low of an estimate, it doesn’t include the Balkan refugees who are sent back and others who are denied asylum. The rhetoric of a swarm engulfing Europe fails to reflect the reality in all countries. While some, like Hungary, are genuinely stretched to the breaking point, others have hardly felt any impact. Britain has so far taken fewer than 300 Syrian refugees this year and has generally seen its levels of asylum seekers drop overall. From a 2011 high of nearly 200,000 refugees, the UK now houses only 117,161, a drop of over 76,000. Spain has received a mere 21,112 applications, one of the lowest in Europe on a per capita basis. Slovakia has taken so few that the number is effectively zero. The real issue is Europe’s uncoordinated policy on refugee resettlement. Germany wants each nation to take its fair share and ease the pressure on Hungary and Greece. But there are no EU rules to require this. As a result, several countries have effectively shut their borders and refuse to take any refugees at all.

7But It’s Still Stretching Some Countries To The Breaking Point

Over the last couple of years, Hungary has opened its doors to nearly 130,000 asylum seekers. While this isn’t a big number, Hungary’s population is so small that it’s creating nightmarish challenges. As one of the main routes for refugees coming through the Balkans, this tiny nation has seen a tide of humanity passing over its doorstep. Leaders have responded by shutting refugees out of its train stations and refusing them onward passage to Germany. Farther south, parts of Greece have been similarly overwhelmed. Already in dire straits financially, the tiny nation has been unable to process thousands upon thousands of applications. As a result, places like the island of Lesbos have seen their population balloon from 90,000 to around 110,000 as 2,000 new refugees land every day. The result has frequently been squalor, as thousands of people are herded into temporary camps that the government can’t afford to maintain properly. Even the countries which pride themselves on being open to refugees may be having more trouble than they’re letting on. Although Germany has flung its doors open to Syrians, The Economist claims that the country is politically reaching its breaking point.

6Many In Europe Welcome The Refugees

Given the potentially explosive scenario described above, it’s easy to assume that all Europeans are united in protest against the refugees. Although some sections of the media paint it this way, it simply isn’t true. In Germany, hundreds of soccer fans at multiple games have taken to unfurling huge banners welcoming the refugees. With European soccer traditionally considered a breeding ground for far-right racism, this is an unexpected turn of events. In immigration-averse Austria, 20,000 recently marched on Vienna to show solidarity with those fleeing persecution. At a temporary migrant camp in Munich, German police were forced to turn away locals when an appeal for food donations resulted in the camp being flooded with parcels. Polls have consistently shown that 60 percent of Germans believe their country is capable of helping even more refugees. Even the frontline Hungarian town of Szeged, one of the cities most affected, has seen thousands donating food, clothes, and medical aid to the refugees on their streets. Similar scenes have been reported in parts of Greece. This isn’t to suggest for a minute that everything is clear sailing. In Eastern Germany, migrant shelters have been torched by neo-Nazis. In Sweden, there are fears of integration among the refugee community. However, it does show that ordinary Europeans are far from united against the newcomers.

5The UK Is Especially Conflicted

With their shared language, many Americans interested in the refugee crisis are turning to the UK for news. However, the UK response has been especially conflicted, with the media blowing it up into a political ball game. Recent polls have shown that the country doesn’t know how it wants to respond to the crisis. One poll reported by ITV declared that roughly half of the British public wants all refugees blocked from entering the country. When asked specifically about people fleeing the Syrian civil war, 47 percent of respondents said that they shouldn’t be welcomed into the UK. When asked more broadly about those fleeing conflict, 42 percent still preferred to close the borders. Other polls have contradicted this. One commissioned by YouGov last summer found that 8 in 10 young Brits were proud of their country’s history of tolerance toward refugees. Different regions are also hugely divided. While pledging to do more to help the refugees, Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has publicly berated David Cameron for refusing to accept more than 300 Syrian refugees. Members of the prime minister’s own party have called his response to the crisis shameful. The media, meanwhile, is tearing itself apart. Toxic language is becoming the norm as the tabloids battle the broadsheets. Interestingly, this is happening despite the UK having one of the lowest levels of migrant influx on the continent.

4The Crisis Could Still Unravel The EU

One of the most notable aspects of the crisis is how it’s acting as a catalyst for many of the issues facing Europe. Despite surviving a banking crisis that nearly sank the entire continent, the EU is now in danger of unraveling. At the forefront of this is the principle of free movement. As part of the Schengen Area, 26 European countries have eliminated border controls between one another, creating an open EU where any citizen can live and work anywhere. This is regarded as one of the bedrocks of Europe. Angela Merkel has made it very clear that Germany considers an EU without Schengen to be destroyed. However, some countries now want Schengen to be eliminated. Denmark is one of many now agitating to have border controls reinstated. Britain is close behind, despite being one of only two EU countries not in Schengen (Ireland is the other). In a different way, Germany is also having problems with the union. Berlin is increasingly frustrated that other nations aren’t taking more refugees, arguing that it’s their humanitarian duty to do so. There’s also the issue of Britain’s upcoming referendum on staying in the EU, which could be held as early as April 2016. Some are worried that the refugee crisis could push the UK to vote to exit. If that happens, Finland has already claimed that “without Britain, there is no European Union.”

3Other Regions Have Absorbed More Refugees

As big as the European migrant crisis is, it’s nothing compared to some other regions. In the Middle East, a number of countries are experiencing some of the fastest population changes seen in human history. Turkey alone has already seen its population expand by 1.6 million as Syrians flee across the border in a desperate attempt to escape ISIS. By the end of the year, the UNHCR estimates that two million refugees will be living in Turkey. Yet this is still a comparatively small number, accounting for around 2.6 percent of Turkey’s total population. In Jordan, the effects have been even greater. This tiny state has taken in 620,000 refugees, equivalent to nearly 10 percent of its population of 6.4 million. With the added strain, Jordan is now in danger of running out of water. In Lebanon, nearly one in five people was a Syrian refugee as of March 2015. That number may now be as high as one in four. Compared to such numbers, Europe has received relatively few refugees. The US has also played its part in the crisis. As one of the biggest refugee resettlement nations on Earth, America takes in an average of 70,000 people every year. Unfortunately, post-9/11 rules mean that it is extremely hard for Syrians to get accepted. So far, only 1,000 Syrian refugees have been accepted into the US, although the White House plans to increase that number to 8,000 by 2016.

2The Effects On The Economy Are More Positive Than You Think

In Europe, the refugee debate often focuses on the effects that an influx of people will have on a nation’s economy. Many believe that migrants and refugees are lured in by excessively generous welfare benefits. This belief is especially prevalent in Britain. It’s also far from the full picture. The welfare state in Britain is fairly miserly. In a 2012 European Commission Report, the UK was ranked alongside Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Estonia, and Malta for its “relatively tight” welfare. Belgium, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, Finland, and the Netherlands ranked highest. It is also hard for migrants to claim unemployment benefits (“Jobseeker’s Allowance”) in the UK, requiring migrants to be in the country for over three months and to prove that they are likely to get work. Even then, they can only claim benefits for six months unless they get a job offer. For refugees, the controls are even tighter. In the UK, asylum seekers receive a mere £36.95 a week to live on, lower than in France. Refugee havens Germany and Sweden pay even less. Then there are the labor restrictions. Both Britain and Sweden have extremely tight rules regarding refugees working, meaning their impact on the job market is minimal. The Economist has argued that this is actually a problem and has called for countries to both accept the refugees and let them work. The newspaper points to studies showing that migrants are net contributors to the public purse, more likely to set up a business, and less likely to commit crimes than native residents. The paper argues that migrants have been shown to raise wages overall. Given Europe’s rapidly aging population, this may be the route that many nations are forced to go.

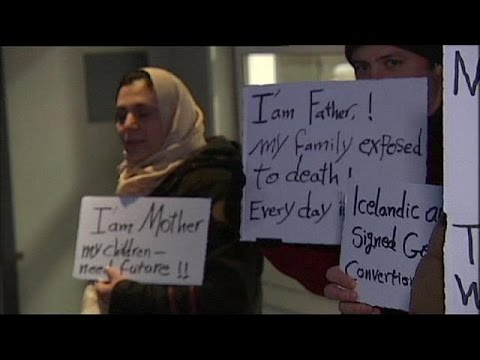

1It’s The Refugees Who Are Really Suffering

With the coverage of Europe’s crisis tending to focus on the impact on the EU, it’s easy to forget who the real victims are. For all the legitimate worries of many anti-migrant Europeans, it’s the refugees who are really suffering. Every day, children are drowning in the Mediterranean as they try to flee persecution. On September 2, 2015, a boy named Aylan Kurdi was found facedown, washed up on a Turkish beach. He and his family had been fleeing the atrocities of Islamic State in the north of Syria and had hoped to reach Canada. He was three years old. His five-year-old brother died with him. In Austria, a truck carrying 71 refugees was abandoned on a roadside in the sweltering summer heat. Everyone inside had suffocated. Among the dead were a two-year-old girl and three boys, ages 8 to 10. By the time they were found, their bodies had decomposed so much that it was nearly impossible to establish an exact death toll. Every day, there are more and more stories like this—from the tale of 150 people who drowned off the coast of Libya to the nearly 2,000 unnamed people who died in a desperate bid to reach Europe between January and April of this year. And still more keep coming. While there may be no easy answers to Europe’s current refugee crisis, the last thing we should do is ignore this unimaginable suffering.