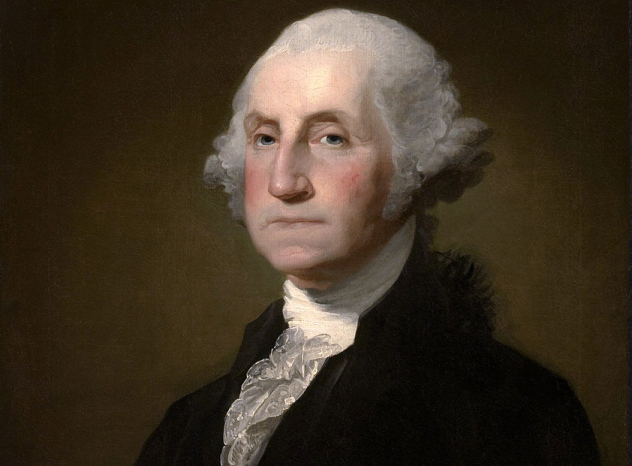

10 George Washington

After George Washington retired, he returned to his plantation at Mount Vernon and promptly began to brew as much alcohol as he could. Then he got bored. John Adams, Washington’s successor, kept Washington’s cabinet. Washington therefore had close working relations with all of them, and they were used to serving under him. Even before he left office, they offered to continue to listen to him, and after a few weeks, he took them up on that offer—without informing Adams. He was particularly interested in foreign policy, especially relations with France, which was a bitter partisan issue at the time. When relations with France completely fell apart in 1798, Washington was ready. The US was seething, and Adams raised a provisional army. There was only one man to head that army, and Washington accepted the job. Problems arose immediately. Washington demanded that Alexander Hamilton be his second-in-command. When Adams tried to appoint someone else, Washington convinced the cabinet to revolt, forcing Adams to hire Hamilton. Washington also grew more and more convinced that the Republicans (which at this time meant anyone aligned with Thomas Jefferson) were traitors and could not be allowed in the army. He upped the ante there by organizing a campaign against Republicans during the Virginia elections, a huge departure from the man who had stayed above party politics for years. When he died in 1799, Washington was as involved in politics as he had ever been.

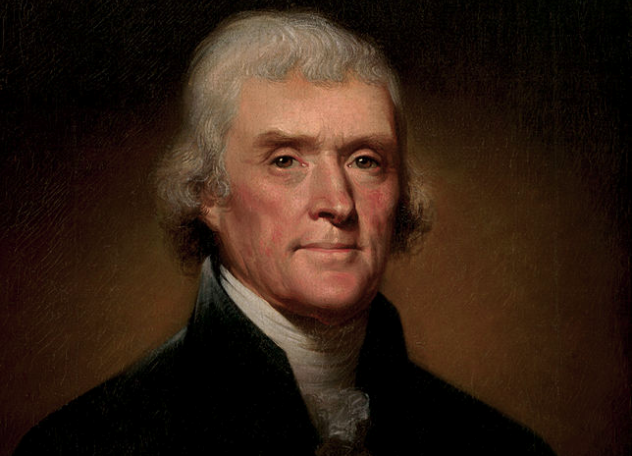

9 Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was still relatively young when he retired. He had time left for a project that he considered among the greatest in his life, one that he deemed worthy of being put on his tombstone along with writing the Declaration of Independence—founding the University of Virginia. When Jefferson founded the University of Virginia, all universities in the United States were controlled by churches, and many solely educated pastors and priests. Jefferson wanted to change that and focused education at the University of Virginia on practical subjects and public affairs. It was also the first university where students could choose their own classes, instead of taking ones chosen by the university. Jefferson was heavily involved in the entire project. He designed the curriculum, hired the teachers, and even designed some of the buildings. He devoted the later part of his life to it, even as his health deteriorated and he fell deeper and deeper into debt.

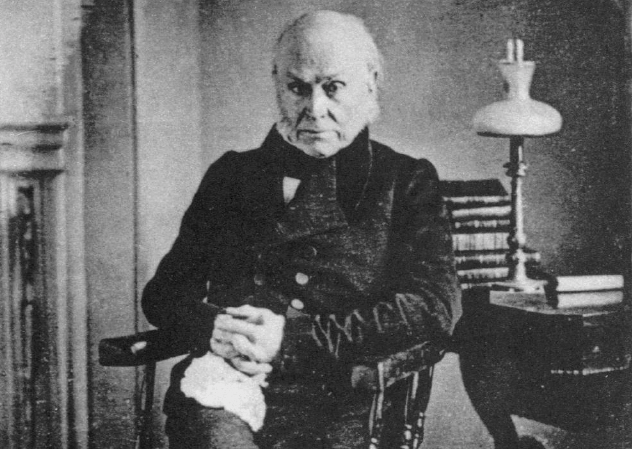

8 John Quincy Adams

After John Quincy Adams lost his reelection campaign to Andrew Jackson, he retired to his hometown of Quincy, Massachusetts, where he quickly became tremendously bored. In 1830, neighbors offered to elect him to the House of Representatives. (It was a simpler time.) He agreed, so long as he was always allowed to follow his conscience. He proceeded to do just that for his next nine Congressional terms. Adams managed to overturn the House’s “gag rule,” which prohibited any criticism of slavery. (Again, it was a simpler, and much worse, time.) He became one of the leading opponents of slavery in the United States, even arguing before the Supreme Court on behalf of a slave rebellion on the Spanish ship Amistad, leading to the slaves being granted freedom. A lifelong champion of the natural sciences, Adams was the primary driver behind the creation of the Smithsonian Institute. He also spent his entire career opposing the Mexican-American War. His final vote was against giving honors to officers who had fought in it.

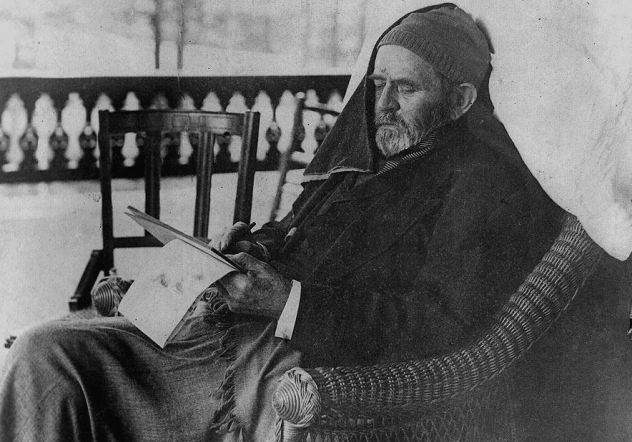

7 Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant declined a third term as president in 1875, mediated the next election, and then left the country. He traveled the world for two years. In that time, he visited three continents, met Queen Victoria, Otto von Bismarck, King Chulalongkorn of Siam, and Emperor Mutsuhito of Japan. While visiting China, he met with the head of the government, Prince Kung, as well as China’s premier general, Li Hung Chang, who asked him to assist in negotiating with Japan, with which China was edging toward war over ownership of the Ryukyu Islands. Thanks to Grant’s intervention, the two countries negotiated a treaty and avoided war. By this time, Grant was homesick and nearly out of money. He returned to cheering crowds, met with friends, and decided it was time to return to the presidency. He ran and was soundly defeated. He returned home, in debt and exhausted. After multiple failed business ventures, he accepted offers from magazines to write articles about the Civil War for some quick cash. Soon, he began to consider writing his memoirs. Since Grant had apparently met everyone important from that era, Mark Twain found out and offered to publish them. Grant accepted, but he learned he had throat cancer shortly after. He decided that wasn’t a reason to quit and kept writing, even as he grew unable to talk, eat, or walk. He completed his memoirs days before his death in 1885. Today, they are remembered as among the best and most important works of American nonfiction.

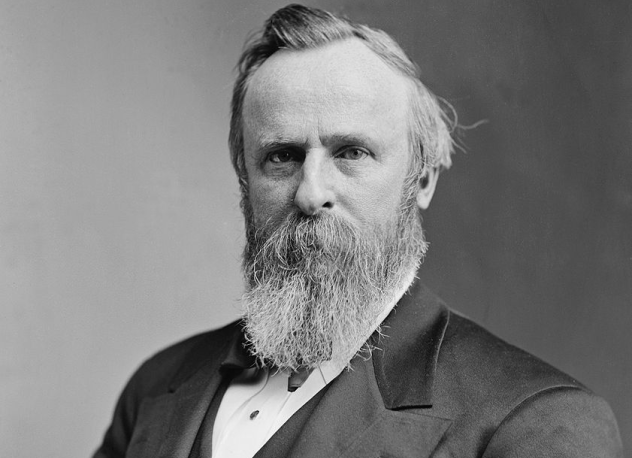

6 Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes is one of those presidents no one thinks about more than once a year. He’s part of that chain of presidents between Lincoln and Roosevelt who didn’t seem to do very much, all had mustaches and funny names, and seemed to exist for no particular purpose. Despite that, Hayes was actually a rather intelligent and educated person with strong views on the issues of his day. Luckily for him, most of his views are ones that most Americans now agree with. After retiring, Hayes devoted his life to various causes, particularly education. He started funds to educate poor children, both white and black, and pushed the federal government to give greater funding to education, as he believed it would create greater equality and democracy. He also favored regulating industry and forcing factory owners to undergo education through work so they would know what it was like to work in their own factory. Hayes spoke out against the growing movement of social Darwinism, saying that education and greater opportunities for the poor would be better than just letting them die. He also argued for heavy taxes on inheritances as a way to reduce economic inequality. A few years before his death, Hayes summed up his political concerns in his diary: “The giant evil and danger in this country, the danger which transcends all others, is the vast wealth owned or controlled by a few persons. Money is power . . . excessive wealth in the hands of the few means extreme poverty, ignorance, vice, and wretchedness as the lot of the many.”

5 Theodore Roosevelt

Did anyone really think Theodore Roosevelt wouldn’t be here? After leaving the presidency in the hands of William Taft, his chosen successor, in 1908, Roosevelt decided to leave the continent in order to give Taft the opportunity to be seen as his own man, independent from Roosevelt. While other presidents might have seen this as an opportunity to wander around Europe for a few years, Roosevelt decided to spend those years in Africa, hunting animals to be stuffed and sent to the Smithsonian. He collected 3,000 in all. Upon returning to the United States, Roosevelt heard from friends, who told him that Taft wasn’t implementing Roosevelt’s programs like he’d promised. Deciding to run for president again, Roosevelt initially tried to become the Republican candidate but found himself blocked by conservatives in his own party. Not dissuaded, Roosevelt founded his own party, the Progressive Party, better known as the “Bull Moose Party.” He campaigned hard and ended up coming in second place in the 1912 election, beating Taft (really badly) while losing to Woodrow Wilson. In the end, however, much of Roosevelt’s progressive platform was carried out by Wilson and still stands today.

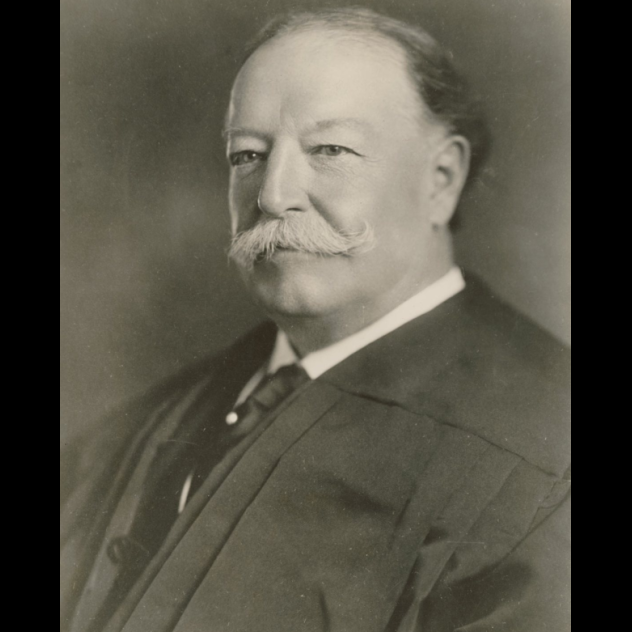

4 William Howard Taft

Taft enjoyed his job after the presidency more than the presidency itself. Of course, that’s because it was the job he’d wanted all along—Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He served for nine years and completely changed how the Supreme Court operated. First, he threw his considerable weight behind the Judiciary Act of 1925, which allowed the Supreme Court to decide which cases it would review. This allowed the Supreme Court to lighten its workload and focus on cases of national importance, something that has profoundly shaped the country, allowing decisions such as Brown v. The Board of Education and 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges. Taft also pushed for the Supreme Court to have a separate building, instead of meeting in the basement of the Senate like the most boring fight club in history. He didn’t live to see the building completed, but now it’s a vital part of how we view the Supreme Court. Taft loved his new job so much that by the end of his life he wrote, “I don’t remember that I ever was president.”

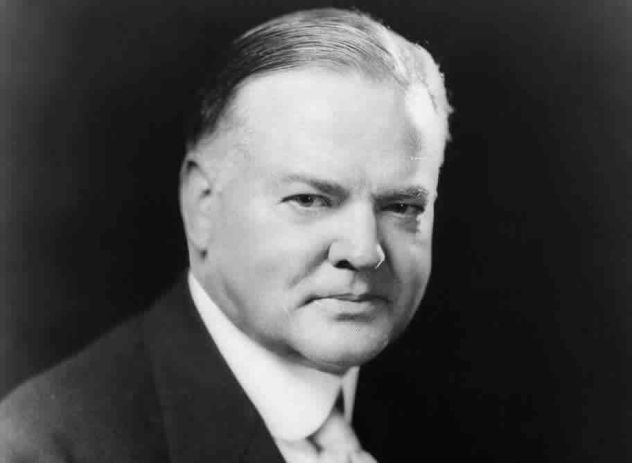

3 Herbert Hoover

Here’s a fun fact: There’s a German word named after Herbert Hoover—Hoover-Speisung, literally meaning “Hoover Feedings.” Long story short, Hoover was instrumental in ensuring that a generation of German children did not experience years of malnutrition. That’s the kind of thing that gets you a word. Hoover wasn’t the best president, given that whole Great Depression thing, but he was possibly America’s best post-president. He largely stayed out of politics during the Roosevelt years but came back in a big way once FDR had died. First, he went to Germany, where he noticed that everyone there was starving to death. He began a program to send tons of American food to Germany to feed the children. All in all, 3.5 million children were fed by Hoover-Speisung, and Hoover quite possibly became the first former president whose fan base consisted of German schoolchildren. Once Germany had ceased starving, Hoover moved on to a much more difficult task than ensuring food supply to a bombed-out wasteland—reforming the federal government. Under both Truman and Eisenhower, Hoover headed commissions that were intended to improve government administration and generally make everything more efficient. He did his job ridiculously well, and over 70 percent of his suggestions were eventually carried out. Hoover also found the time to write 16 books, including several best sellers, because why not? By the time he died, Hoover had managed to become highly respected throughout the United States, which isn’t bad for a man whose main accomplishment as president was the Great Depression.

2 Jimmy Carter

Jimmy Carter has probably had the most recognizable and famous post-presidency. He’s been extremely active in promoting health, development, and peace all over the world, both through his own organization (the Carter Foundation) and the Elders, a sort of super group of very peaceful old people, including seven Nobel laureates. Beyond that, he’s led the fight to eradicate guinea worm disease, which has been around as long as humans have existed. Guinea worm larvae lie waiting in stagnant water and then enter the body via drinking. It incubates and emerges a year later at nearly 1 meter (3 ft) long by burrowing through the skin. This is, for obvious reasons, ridiculously painful, and the side effects of having a worm in your body leave people unable to work or care for their families for years. When the Carter Center began its work in 1986, guinea worms infected 3.5 million people per year. In 2014, that number had been reduced to 124. By the Carter Center’s estimate, guinea worm disease is soon to become the second disease, after smallpox, to be completely eliminated among human beings. Also, since eliminating a disease as old as humanity isn’t enough, Carter has assisted in negotiations with North Korea, served as an ambassador between Israel and Palestine, helped to negotiate peace between Sudan and Uganda, overseen elections in Venezuela, written 21 books, and now, at the age of 91, has hopefully beaten brain cancer.

1 Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton’s post-presidential actions can be divided into two groups—helping to eliminate disease, suffering, and poverty worldwide and helping Hillary to try to become president. We’ll begin with the latter. For those readers who just awoke from a decades-long coma and are now discovering this “Internet” thing, Hillary Clinton is Bill Clinton’s wife, and she really, really wants to be president. Bill Clinton has thrown his support completely behind her, almost as if he’s trying to make up for some kind of past indiscretion. He was actively involved in her 2008 presidential campaign and is even more so in her 2016 campaign. He’s helped edit her speeches, raised money, given speeches, and has given her advice for staying calm during the Senate inquiry about Benghazi. However, most of his time still seems to be taken up by post-presidential duties (mostly serving as a symbolic representative of the United States in other countries), as well as his work with the Clinton Foundation. The Clinton Foundation is one of the largest charities in the world, with an incredible amount of assets and areas of interest. It’s donated billions of dollars to rescue people from poverty and disease and was one of the main engines driving donations to the Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina and to Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. Bill Clinton has been at the center of it all, traveling the world, collecting donations, and implementing programs.