The St. James’s area of London soon became known as Clubland, with dozens of clubs springing up for the benefit of gentlemen with nothing much to do with their time. Behind closed doors, however, many of these organizations were and continue to be very ungentlemanly indeed.

10 White’s

White’s is one of the oldest gentlemen’s clubs in London, dating from the early 18th century. It is said to have been the inspiration for the gaming house in The Rake’s Progress. White’s was a noted gaming house and often considered a den of iniquity. Dinner at White’s is a long, formal event with many courses served by intimidating waiters. It is followed by port and cigars aplenty. White’s maintains a Betting Book which records the details of every wager placed there. Few of those bets are concerned with horse racing or sport in any form. Rather, they were bets about the length of a person’s life or which raindrop would reach the bottom of the windowpane first. Other notable bets included whether the editor of a prominent newspaper would go to prison for libel and whether HRH the Duke of Clarence (who became King William IV) would father a legitimate child within two years. As shown by one peculiar entry on November 4, 1754, two members had a bet on which of two other elderly members would die first. Although the bet was a considerable one, it was never paid because both men who placed the wagers killed themselves before either of the two elderly gentlemen died.[1] The reason for the suicides? Gambling debts. One of them even lost £32,000 in a single night. In more recent times, the club was the recruiting ground for the Cambridge Spies, those Eton and Cambridge graduates with every material advantage who spied against their country.

9 Boodle’s

Boodle’s, named after one of its waiters, was established in 1762 by the Earl of Shelburne. Membership has always been by election only, with many hopeful applicants refused entry. The aims of the club were nominally political, but it was acknowledged that “wining and dining, gaming and betting” were always going to be important elements of the club. The tradition of gambling at Boodle’s has continued ever since. The members, including the dandy Beau Brummel, recorded their bets in the betting book. Indeed, Brummel noted his final bet in the book right before he fled London to avoid paying his massive gambling debts.[2] But gambling was not restricted to the club. In 2002, the former chairman of Boodle’s admitted to a £4 million fraud to cover his investment losses and membership fees at the club. Boodle’s was the inspiration for the fictional club, Blades, of which James Bond was a member.

8 The Clermont Club

The Clermont Club was opened in 1962 by John Aspinall, an eccentric millionaire and zoo owner. It was designed from the beginning as a casino for the use of the superrich. During the swinging ’60s, the club was famous for its opulence and high-stakes gambling. Guests included actors, politicians, and even royalty. Roger Moore, Frank Sinatra, and Princess Margaret were regular visitors, and the membership included at least five dukes, eight viscounts, and 17 earls. Lord Lucan was a regular visitor to the casino and a personal friend of Aspinall. On the night of Lucan’s disappearance, he visited the club and settled his debts. Just hours later, his children’s nanny was found bludgeoned to death. The most popular game at the casino was a card game called chemin de fer. The Earl of Derby is said to have lost half a county in a single evening’s play. It is alleged that Aspinall, facing big losses at the club, began to use marked cards in the casino to reduce his liability. However, this has never been proven.[3]

7 Brooks’s

Brooks’s was founded in 1762 by two gentlemen who had been blackballed for membership at White’s. The premises of the original club were on the site of a former tavern. Its members, known as Macaronis, frequented the club for the purposes of wining, dining, and gambling. The club is now in a much grander building. To this day, it has a number of gaming rooms where fortunes have been won and lost.[4] After a particularly lavish dinner at Brooks’s Club, an earl bet a duke 500 guineas that the duke couldn’t have sex with a woman “a thousand yards up” in a hot-air balloon, thus paving the way for the formation of a different sort of club.

6 The Reform Club

The Reform Club was founded in 1836. Membership was originally restricted to those who pledged support for the Great Reform Act of 1832 and was thus mostly an organization for members of the Liberal Party. Today, it holds no particular political affiliation. Its membership is not limited to gentlemen only as it was one of the first clubs to admit women. In recent years, the club has been at the center of allegations of bullying and discrimination among staff and elected officials, but the confidential nature of the organization has prevented the details from being made public. However, several club officials have been paid handsomely to leave the organization and never return.[5] The Reform Club was the one that Phileas Fogg famously departed when he bet members £20,000 that he could circumnavigate the globe in 80 days in Jules Verne’s classic novel. However, despite being one of the largest clubs in London with some very rich members indeed, it still occasionally has to resort to consorting with “trade.” In 2017, they rented out the entire club to Cartier for a jewelry exhibition, and the members had to drink elsewhere for a month.

5 The East India Club

Billed as a “gentleman’s home from home,” the East India Club was founded in the mid-19th century. However, what it lacks in age, it makes up for in wealth and opulence. And scandal. Originally set up for officers of the East India Company, it soon opened its doors to “gentlemen” of all persuasions. Members had to be nominated, usually by the headmasters of the exclusive private schools that they attended. The club has continued to keep to tradition, refusing to allow women to become members. “Ladies” are occasionally allowed in on special occasions as long as they know their place and enter through the back door.[6] The East India Club has steadfastly refused to move with the times. Even when their treasurer appropriated £500,000 from their accounts, their first concern was discretion rather than prosecution. The organization was also the scene of an ugly blackmail scandal when a British member of parliament claimed expenses to stay at the club during an extramarital affair. A colleague attempted to blackmail him by filming him leaving the club with the mistress.

4 The Albemarle Club

The Albemarle Club opened in 1874. In an unusual move, it opened its membership to both men and women from its inception. At the time, this was considered both progressive and, in some minds, almost scandalous. (Some clubs, such as London’s Garrick Club, still refuse to allow women to become members today.) The Albemarle Club attracted a wide range of artists, writers, and intellectuals. Now defunct, the organization is remembered chiefly for its association with Oscar Wilde and the night when the Marquess of Queensberry hammered at the door of the club. The marquess was a short-tempered and somewhat intolerant man, made famous for developing the rules of boxing. Believing that Wilde had corrupted his son, Lord Queensberry tried several times to forbid their friendship. He wrote to his son in terms that can only be described as “strong” and signed off as “your disgusted so-called father.” The marquess believed that Wilde had been having an affair with his son and, being denied entry to the Albemarle Club, left a card for Wilde with the doorman. It read: “For Oscar Wilde posing as a sodomite.” Despite his embarrassment, Wilde would have done well to let the matter pass. But he did not. Fearing that his reputation would be ruined by the marquess, who had also tried to storm the stage during the opening night of The Importance of Being Earnest to inform the audience of his suspicions, Wilde sued for libel. The doorman of the club was called to testify. Given his damning testimony (and the parade of young men whom the marquess had found to testify to having been Wilde’s lovers), Wilde was sentenced to two years imprisonment in Reading Gaol and his career was over.[7]

3 The Presidents Club

Not a gentlemen’s club as such, the President’s Club was a charity that hosted men-only fundraising dinners. The dinners might have been described as “lively, raucous, and filled with sexual harassment.” Scandal engulfed the charity when an undercover journalist working for the Financial Times posed as a waitress at the event. The waitstaff were all chosen because of their good looks and were told to wear sexy black dresses and black underwear. In the pre-event briefing, they were also warned that some of the men might become, shall we say, overly familiar but that this was all part of the “fun.” The ball was attended by prominent politicians, businessmen, and celebrities, all of whom claimed to be unaware of what was happening. No one saw anything untoward. However, when the newspaper published their evidence with secret film of how the serving staff was treated, the charity was forced to close its doors for good.[8]

2 The Savile Club

The Savile Club was born out of scandal. Their current building was bought from the widow of Viscount Lewis “Loulou” Harcourt. He had married a very wealthy woman, and after resigning as an MP upon succeeding to his peerage, he spent most of his time engaging in his hobby—which was pedophilia. He was said to have had the “finest” collection of child pornography in the country by the time he killed himself at age 59. His predilections had been an open secret in English society, with Eton boys in particular being warned never to take a walk in his company. However, his secret eventually reached the ears of the police. On the eve of his arrest in 1922, he blew his brains out. Writer H.G. Wells was once asked to resign from the club after his mistress became pregnant. The mistress happened to be the daughter of a fellow member. She quickly married another man to avoid a scandal. (Wells was not available because he was already married.) Even so, they continued the affair. Daily, the mistress’s father waited in the club with a revolver to confront Wells until the committee felt that Wells ought to resign in the interests of safety.[9]

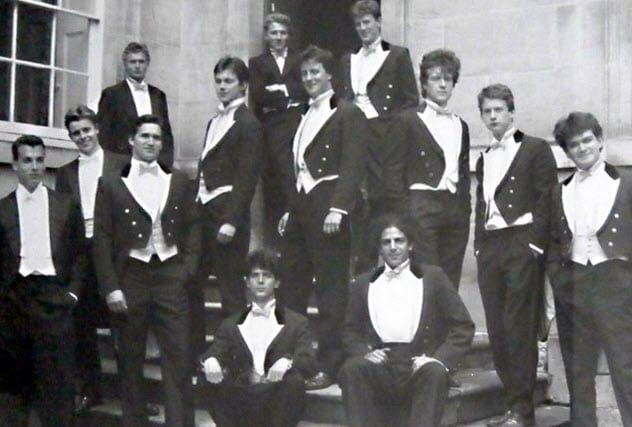

1 The Bullingdon Club

Officially called a dining society, the Bullingdon Club has no premises. Members are recruited from current Oxford University students, and most of those who are invited to join have also been to Eton. And they need to be rich. Very rich. The club uniform—full evening dress with a tailcoat of Bullingdon blue—is made by one tailor only and costs around £3,500. There are no club fees. But potential members need to consider the costs—not only of the food and drink but also of the repair bills. The members are famous for trashing restaurants on a night out and then tossing money to the patrons as they leave to cover the damages. The proceedings of the club are secret, though it was rumored that one member burned a £50 note in front of a homeless man as part of his initiation ceremony. Nice. Although the club has existed since 1780 when its primary interests were listed as hunting and fishing, the organization has seen a steep decline in membership over the last 15 years. This is not surprising, considering some of their previous antics. In May 1894, the members managed to smash almost all the lights and all 468 windows in Peckwater Quad, Christ Church, in Oxford. If that wasn’t enough, they recreated the moment in 1927 and smashed them all over again. Bullingdon is no longer on the approved list of clubs at Oxford University, and membership has waned. This is partly due to a scathing representation of the organization in the film The Riot Club, which showed the excesses and arrogance of club members.[10] Ward Hazell is a writer who travels and an occasional travel writer.

![]()