10 The Amboyna Massacre

The island of Ambon in the Moluccas was a rich hub of the spice trade shared between the English and Dutch. After several years of bloody conflict, the English and Dutch East India Companies agreed to peace in 1619, but Dutch ships continued to harass English merchant vessels, increasing the cost of pepper in England. In 1623, a Japanese mercenary paid by the English was discovered by the Dutch prowling around and asking suspicious questions about fortifications, leading the Dutch merchant-governor Herman van Speult to believe the English were about to launch a strike against them. Several Japanese mercenaries were tortured until they revealed an English plot against the Dutch, and several Englishmen were later also captured and tortured. As the English had fewer than 20 men on the island and no prospect of reinforcements, the Dutch had 200 European troops, 300 native troops, and a number of Japanese mercenaries, so the plot was pretty unrealistic. But von Speult didn’t care. After forcing the chief English factor Gabriel Towerson to confess to the plot through torture, von Speult put 10 Englishmen and nine Japanese mercenaries to death by beheading, allowing those who freely admitted to the plot to leave the island. Those put to death protested their innocence in notes smuggled off the island: “tortured with that extream (sic) Torment of Fire and water, that Flesh and Blood could not endure it, and we take it upon our Salvation, that they have put us to Death Guiltless.” The executions and their dubious legality led to a spike in anti-Dutch sentiment in an enraged English public, complicating the relationship between the countries for generations.

9 Vasco da Gama’s Campaign Of Terror

In 1502, Vasco da Gama led the third Portuguese expedition to the Indian Ocean with a fleet of 20 ships sent to wrest control of the trade routes from Muslim powers. The Portuguese had built a factory in Calicut several years earlier, believing they had been given a monopoly over the local spice trade. This was a mistake. After they seized a vessel bound for Jeddah, they were massacred by the furious Muslim traders. The Portuguese responded by destroying 12 Muslim vessels and bombarding Indian ports, but they still wanted their revenge and monopoly. Da Gama was the man chosen to get it. Da Gama was dubbed Captain Major of the expedition with a special decree by the king. Arriving near Cannanore (present-day Kannur), India, he wasted no time in beginning a campaign of terror along the Arabian coast, attacking and raiding coastal communities. After a few days of searching for ships returning from the Arabian sea for pillage, the Portuguese spotted the Meri, a Gujarati or Egyptian ship carrying Muslim pilgrims back from Mecca, including some of the most wealthy people of Calicut. The Portuguese fired warning shots at the unarmed Meri. Da Gama negotiated with a wealthy man named Jauhar Al Faquih, who first offered the Portuguese money, then his own wife, his nephew as collateral, and four ships’ worth of spices. He even offered to help establish good will between da Gama and the ruling Zamorin of Calicut. But da Gama demanded everything. After stripping the vessel of a lot of wealth (as well as 20 children he vowed to make friars in the Church of Our Lady at Belem), da Gama initially offered five ships’ worth of food in return, then ordered his men to set parts of the Meri on fire. The Portuguese sailed away, but after seeing the pilgrims had put out the fires, da Gama went back to start them again. The pilgrims offered even more wealth and jewels, but da Gama was intractable. He wanted revenge for the deaths of Portuguese in Calicut several years earlier. The Portuguese confined the pilgrims below decks and stoked the fires with gunpowder charges for several days while preventing the ship from escaping, which eventually caused the ship to sink, killing almost 400 people aboard. Da Gama then moved closer to Calicut, where his men captured and dismembered 30 fishermen and left their bodies floating for their families to find.

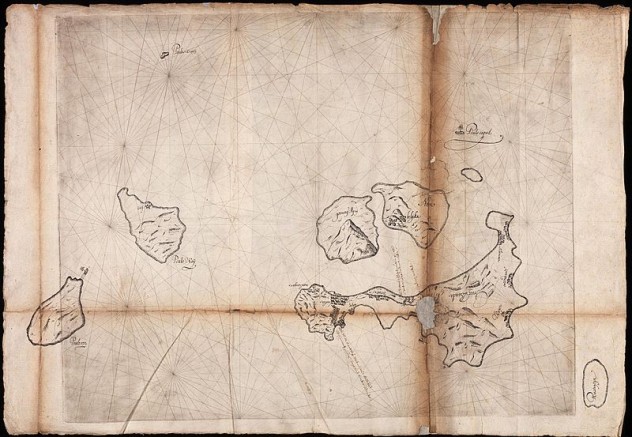

8 Banda Islands Massacre

Nutmeg was a highly popular spice in Europe in the 15th century, used for flavoring and to disguise the taste of poorly preserved meat. It was also believed to be a cure for the plague, so women wore nutmeg satchels around their necks to protect themselves from the pestilent air. Nutmeg that cost a penny in Asian markets could fetch two pounds, 10 shillings on the London streets. The profits were on the order of 68,000 percent. Nutmeg was found at a single source, the Banda Islands in the East Indies, where sultans maintained a neutral trading policy with the spice-crazed European merchants. The Dutch coveted control of the Banda Islands, where the trade was monopolized by the Portuguese. So in 1612, the Dutch East India Company swept in and seized control of the islands. The Dutch established a strict and paranoid policy of protection, banning the export of trees, drenching nutmeg in lime to render it infertile before export, and imposing a death penalty on those caught stealing, growing, or selling it. When the local inhabitants rebelled against the rules, company head Jan Pieterszoon Coen ordered a massacre. The Dutch set about executing every Bandanese male over the age of 15 by quartering and beheading. Village leaders were beheaded, their heads placed on poles outside villages. Within 15 years, the Dutch reduce the island’s population from 15,000 to 600. One of the islands, Rum, escaped for a time thanks to the protection of the British, but after several failed attempts at the military seizure, the Dutch gained control of that island as well when they gave up control of a seemingly insignificant and unpromising island halfway around the world: Manhattan. Nutmeg helped make the Dutch East India Company the richest corporation in the world—at least until 1770 when French horticulturist Pierre Poivre managed to break the Dutch monopoly by smuggling some nutmeg to Mauritius. A tsunami destroyed half the nutmeg trees in Banda in 1778, and they were captured by the British in 1809.

7 Battle Of Diu

The Battle of Diu is considered one of the most decisive naval battles in history and helped to turn the Indian Ocean into a Portuguese lake. An international coalition had formed to unite the Ottomans, Egyptians, Gujaratis, Calicutis, Venetians, and Ragusans to expel the Portuguese interlopers and preserve established trade routes through the Red Sea and Arabian Gulf. A joint fleet of the ships of the Sultan of Gujarat, the Mamluk Burji Sultanate of Egypt, and the Zamorin of Calicut was formed with Ottoman, Venetian, and Ragusan support. In 1508, Mamluk admiral Amir Husain Al-Kurdi surprised a Portuguese fleet and killed its commander, Lourenco de Almeida, the son of Viceroy Francisco de Almeida. The next year, however, the viceroy got his revenge. The Battle of Diu was fought in 1509 and seemed terribly lopsided. The coalition had a great advantage over the Portuguese with their 100 ships, firepower, tonnage, and fighting men. The Portuguese had only 18 ships under the command of Viceroy Francisco de Almeida, but they had a crucial advantage. De Almeida’s fleet had better artillery with better trained gunners, seasoned and professional crews, and better arms and equipment including armor, arquebuses, and a new kind of clay grenade stuffed with gunpowder. The coalition fleet comprised Mediterranean war galleys hastily built in Egypt, Indian dhows, and a couple of new Venetian ships. The sailors were relatively green, mostly Greek sailors and Turkish mercenaries armed with bows and arrows. The heavily armed Portuguese carracks and caravels were larger and had a greater range than the joint fleet. Their powerful cannons kept the smaller craft from approaching, and when they did, the galleys and dhows were too low in the water to allow their crews to board the enemy ships while the Portuguese rained bullets and grenades from above. The joint fleet was destroyed while the Portuguese did not lose a single ship. The colors of the Egyptian Sultan and Admiral Amir Husain were captured and sent back to Portugal. No fleet would challenge the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean again until the arrival of the English and Dutch. Some ships of the joint fleet were captured and kept as war booty. Among these were two newfangled ships known as galleons, which had been built by the Venetians and performed well in the battle. These galleons would eventually be copied by the Portuguese, further helping to cement their stranglehold over the Indian Ocean.

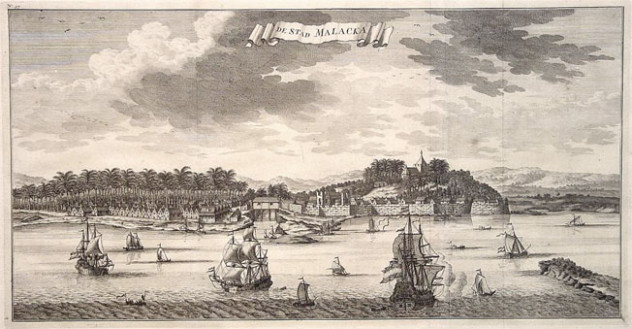

6 Conquest Of Malacca

Malacca was a wealthy trade hub ruled by a Muslim sultan said to have descended from the Javanese who seized control of the peninsula from the Kingdom of Siam centuries earlier. The city was cosmopolitan, lying on the crucial trade link between East Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It was divided into four districts representing the main trading groups—the Chinese, the Javanese, the Gujaratis, and the Bengalis. The Malay peninsula had been first visited by Diogo Lopes de Sequeira in 1509 when it was known to the Portuguese by its classical name, the Golden Chersonese. Fruitful trade seemed likely to ensue after a factory was set up, but the Malaccan prime minister was advised to destroy the Portuguese fleet by Muslim merchants. A plan was made to invite the fleet’s officers to a banquet, murder them, and capture their ships. A Javanese woman who had fallen in love with a Portuguese man swam out to the squadron to warn them, but the officers ignored her warning. The Malays seized the factory and captured about 20 men, including chief factor Ruy de Araujo. De Sequeira abandoned them and sailed back to Portugal, sending two ships to the Malabar coast to report the situation to Viceroy Afonso de Albuquerque. De Araujo sent letters to de Albuquerque complaining of being forced to convert to Islam, and the viceroy put a fleet of 18 ships together to stage a rescue and take revenge on the Sultan of Malacca in 1511. Negotiations continued for weeks. The Portuguese demanded the prisoners before signing a treaty, and the Sultan demanded a treaty before releasing the prisoners. The Malays built up their defenses, but when Albuquerque set fire to some boats and buildings near the harbor, the Sultan relented and released the prisoners. De Albuquerque was sure the Sultan was planning something and was advised by de Araujo that control of the city rested on a particular bridge uniting the two halves of the city. Plans were made to launch an attack on July 25, the day of the viceroy’s patron saint, Saint James the Greater. The first push to seize control of the bridge failed, but some cannons were captured and fires ripped through the city, including the royal palace. A second attack was made when the Portuguese sailed a tall junk converted into a siege ladder to the bridge, which they then captured and defended while other troops used the diversion to make a landing elsewhere. An attempt by the Sultan to use the strength of his war elephants backfired when the Portuguese held their ground and the elephants panicked, knocking their riders—including the hapless Sultan— to the ground and crashing back through the Malaccan lines. The Portuguese retired to their ships. When they returned a week later, they discovered the Sultan had fled inland. The Portuguese seized an enormous booty of gold, silver, jewels, silks, and spices. A Portuguese administration was set up over the city, and a fort was built with stone taken from local mosques and tombs of former sultans.

5 Massacre At Bantam

One of the first Dutchmen sent to break the Spanish and Portuguese hold on the spice trade was Cornelius de Houtman, by all accounts a decidedly unsavory figure. He had secured the position due to personal connections. De Houtman was unpredictable, incompetent, and erratic. One of his ships sank, taking 145 sailors’ lives. He openly insulted the local merchants, who were nonetheless pleased to see some competition to the Iberian powers, and carried some ill-advised choices in trade merchandise for the sweltering tropics, including heavy woolen cloth and blankets. Discipline aboard ship had broken down, though a truce had formed by the time the fleet reached Sumatra, where the natives rowed out in dugout canoes to exchange rice, watermelons, and sugarcane for glass beads and trinkets. They soon arrived in the wealthy port of Bantam, where de Houtman hoped to buy spices at low prices. He had arrived at a time of political turmoil, however, and bickering traders had driven the prices up immeasurably. De Houtman was furious. In the words of one crewman: It was decided to do all possible harm to the town. Bantam was bombarded with cannon fire, and all prisoners were put to death. The fighting paused briefly as the Dutch commanders debated the best way to dispose of the prisoners: stabbing them, shooting them with arrows, or bombarding them with cannons. Soon the attack resumed, with the local king’s palace hit by cannon fire and one group of prisoners tortured seemingly for the hell of it. Another crew member wrote, “After we had revenged ourselves to the approval of our ship’s officers, we prepared to set sail.” They sailed onto the port of Sidayu, where they were attacked by a group of natives who boarded one of the ships, hacking 12 Dutchmen to death. The Dutch counterattacked, pursuing the Javanese in rowboats and executing them. They then sailed onward, straight toward another massacre.

4 Madura’s Welcome Party

De Houtman was still fuming about the attack near Sidayu when he arrived at the island of Madura off the Javanese coast. The locals were blissfully unaware of the massacre at Bantam and made efforts to welcome the Dutch visitors. The local prince had planned a welcome parade with a flotilla of prau boats, which slowly sailed toward the Dutch with a large and magnificent barge in the center for the prince. As the prau boats approached, the Dutch began to fear an attack, suspecting an ambush or similar treachery. Better safe than sorry, de Houtman opened fire on the flotilla, killing everyone aboard the prince’s barge. Cannon fire sank most of the boats, then the Dutchmen lowered rowboats and concluded the massacre with hand-to-hand combat. Only 20 natives on the flotilla survived de Houtman’s paranoia. The prince’s body was robbed of its jewels and dumped into the water. One sailor described the scene: “I watched the attack not without pleasure, but also with shame.” Despite their victory over their welcome party, the Dutch fleet was in dire straits. The crew was wracked by tropical diseases, bickering factions backing differing commanders had formed, and the ships were covered in barnacles, honeycombed by shipworms, and dried out by the beating sun. And they hadn’t even acquired their spices yet. A dispute with another commander, Jan Meulenaer, about whether to sail to the Banda islands or return home ended with Meulenaer’s suspicious death during an argument with de Houtman. It was obvious he had been poisoned. De Houtman was arrested, though he was released thereafter. It was eventually decided to give up and go home without any spices, with two out of every three crew members dead due to disease or misadventure, hardly any spices, and a trail of carnage behind them. What little de Houtman had been able to buy or steal was enough to make the whole venture profitable thanks to high inflation in the cost of spices in Dutch markets while the fleet had been away.

3 The Dutch-Portuguese War

In their struggle for independence from Spain, the Dutch decided to hit the enemy where it hurts most and disrupt Spanish and Portuguese trade routes in Africa, the Americas, and Asia. Both Portugal and Spain were under the rule of the Hapsburgs, the hated enemies of the Dutch. This was a global effort. One of the most profitable components of the Iberian trade system at the time was the Portuguese trading stations set up in the Indian Ocean and Asia. By disrupting these routes, the Dutch could enrich themselves for the war effort at the expense of their enemies. It was also revenge for Philip II and Philip III banning Dutch ships from entering Spanish or Portuguese harbors. Dutch merchants with expertise in the Spanish and Portuguese trading system were expelled from Antwerp after it was captured by the Spanish, taking their valuable knowledge with them. Between 1597 and 1602, 65 Dutch ships sailed for Asia—about 13 a year. In 1602, regional trade companies were merged into the Dutch East India Company, or Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC). Though it would become famous later for its trading empire, it was initially an instrument of war, receiving federal government subsidies while racking up huge debts. Between 1597 and 1609, the Dutch captured 30 Spanish and Portuguese ships in Asia, most of which were probably trading vessels. This was an average of two or three a year. The number of Portuguese ships sent to Asia was usually between 5 and 10 each year. The Dutch attacks on the Spanish and Portuguese trade in Asia in addition to their other efforts in Africa, Brazil, and the Caribbean took an economic toll. It is arguable whether the Dutch attacks on Portuguese shipping did immeasurable damage or merely impeded their growth. Some indicate the period was actually a boom for Portuguese shipping and point to their successes against the Dutch in Brazil. The war set the foundation for the growth of the Dutch maritime empire, which would form alongside the Iberian trade system and eventually eclipse it.

2 Portuguese Conquest Of Ceylon

In the early 16th century, the Portuguese dominated the spice trade in India. They had their eyes on the island of Ceylon—present-day Sri Lanka—which was famous for its cinnamon. The island was divided into four kingdoms—Kotte, Sitawaka, Kandy, and Jaffna. The Portuguese planned tactics similar to those used to acquire the Malabar coast, looking for a local ally with whom they could sign a commercial treaty and then use as support against their rivals. In 1518, Viceroy Lopo Soares de Albegaria landed near Colombo with a large fleet and set up a fort. After crushing some resistance, he forced the king of Kotte to become a vassal of the king of Portugal, unlike the kings on the Malabar coast who were considered “friends.” An agreement was engraved on sheets of beaten gold in which the king promised to pay 300 bahars of cinnamon, 20 ruby rings, and six elephants. The fort was reinforced the following year to withstand the sporadic attacks often raised by Muslim merchants who were angry about the competition in the cinnamon trade. During one siege, the Portuguese are said to have launched a counterattack in which they seized a nearby town, tied the women and children to doorways, then set the city on fire. Over time, the Portuguese presence slowly grew despite the resistance by local powers. In 1597, King Philip of Spain and Portugal also became king of Ceylon, as only the kingdom of Kandy remained outside Portuguese control. Kandy established friendly relations with the Dutch, and although the Kandians were later neutralized as a threat by the Portuguese, the Dutch systematically pushed the Portuguese off the island over the course of the 17th century to seize control of the cinnamon trade.

1 The War Of Chioggia

Long before the Atlantic powers rounded Africa and stuck their noses into the Asian trade system, trade of spices and other Asian commodities was dominated by Mediterranean powers like Venice and Genoa. These two maritime republics had a great economic rivalry, and Venice feared Genoese attacks against its trading stations in the Levant and the Black Sea. In 1378, two Venetian fleets were sent to harass the Genoese, the smaller fleet under the command of Vettor Pisani to the western Mediterranean and the larger fleet under the command of Carlo Zeno to attack Genoese trading stations in the Levant Sea. While Pisani’s fleet wiped out a Genoese fleet off the coast of Italy, Zeno harassed Genoese trading stations in the east. The Genoese were at first taken aback but soon rallied and decided to take advantage of the fact that Zeno’s best ships were busy elsewhere. In 1379, a Genoese fleet was sent to attack Venice directly, which was also being harassed on the mainland by Hungarians allied to Genoa. Pisani encountered the Genoese and tried to withdraw, but he was forced to engage the enemy by commissioner Michael Steno, who had authority granted by the senate over the admiral. The Venetian fleet was largely destroyed. After the arrival of reinforcements, the Genoese launched an attack on the city itself with the support of the Hungarians and Carrarese. The Venetians had closed the outer bank passages and set up formidable defenses, but there was a gap near the island of Brondolo and the town of Chioggia. The town was separated from Venice by a lagoon with shallow waters and intricate passages difficult for the heavy Genoese vessels to navigate. Pisani, who had been imprisoned, was released and made commander in chief. He developed an ingenious way to defeat the enemy. In a series of night attacks, he sank a number of vessels laden with stores, blocking the route from Chioggia to Venice and the route to the open sea, effectively trapping the Genoese. For a year, Venice and the Genoese fleet engaged in a besieging game of chicken. Zeno returned from his adventures on New Year’s Day, 1380, and the Venetians attacked the Genoese with greater vigor. By the middle of the year, the besiegers had no choice but to give up. The war was both a victory and defeat for Venice, which was still forced to give up the island of Tenedos and recognize Genoa’s sovereignty over Cyprus. But it pulled the city together and kept it from succumbing, allowing the Venetians to continue to expand their trade routes in the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean, where they would dominate the spice trade until navigators from the West found their way around Africa. David Tormsen has not yet had to murder and pillage for deliciousness. Email him at [email protected].