When the Populares faction were in power, the government actively worked to empower the people at the expense of the elites. Senate funds were used to buy farms off wealthy people and then give them to the poor, as well as to establish hospitals where the poor could be treated for free. Most public buildings were built and maintained with government money and charged very little for entry. Here, we study ten of the ways ancient Rome was surprisingly progressive.

10 Free Food

In the early years of the Roman Empire, Rome’s population grew rapidly.[1] At the same time, wealthy landowners were buying up agricultural land outside the city, forcing poorer farmers to head to the city for work. The result was a large, impoverished group of people who struggled to find regular work. Gaius Gracchus’s grain law of 123 BC tackled this by offering grain at half the market price once a month to anyone who was willing to stand in line and wait for it. The practice of doling out grain to Rome’s poorest would last another six centuries. The system was overhauled during the reigns of Julius and Augustus Caesar. From then on, the grain would be completely free, but only Rome’s poorest 200,000 people would be eligible. They introduced a test which determined who the poorest were. Though the grain was free, the people still had to pay for the materials and skills to have the grain turned into bread, unless they were able to do it themselves. In AD 270, Emperor Aurelian altered the system, replacing the grain with fresh bread, and introduced a system where pork, oil, and salt were also regularly distributed for free. The policy finally came to an end when the empire fell in the fifth century.

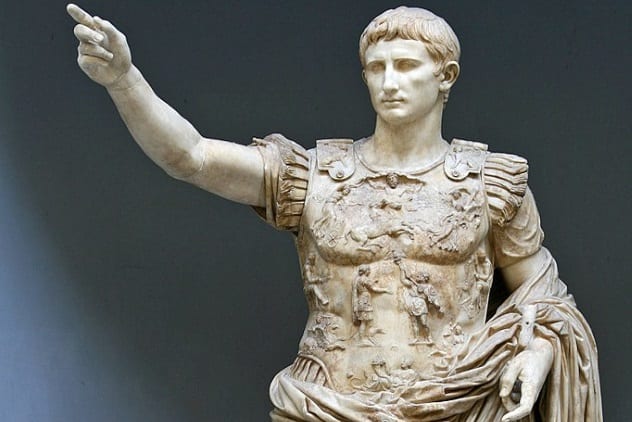

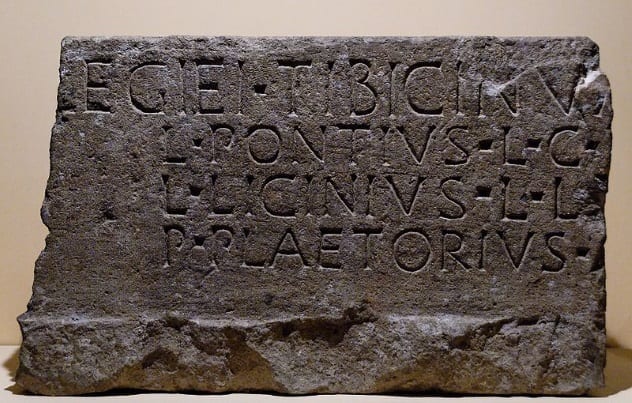

9 Military Pensions

Throughout the history of the Roman Empire, soldiers received a pension upon completion of their military service (16 years for Praetorians, 20 years for regular legionaries).[2] In the early years of the empire, payment was usually in the form of land. However, the land was often either newly conquered and on the empire’s border—where it was vulnerable to raiders—or publicly owned land that was often rented or in temporary use by other tenants. Neither of these scenarios were particularly satisfactory for the average soldier, and they often led to land disputes. In AD 6, Augustus Caesar scrapped the system and replaced it with a monetary payment scheme. From then on, each legionary received 12,000 sesterces when he was honorably discharged—along with a bronze plaque that recorded his completion of service. The value was equal to around 12 years of legionary wages and would have been more than enough to allow the soldier to buy a property with money to spare. Augustus injected 170,000,000 sesterces from the imperial treasury to start the system and maintained it with a five-percent tax on inheritance and a one-percent tax on all goods sold at auction. Many of the wealthy Roman elite complained, since the taxes were hard on them personally, but the system benefited Rome in the long run by making soldiers reliant on the emperor himself for their pensions. It also guaranteed that anyone, regardless of class, could enjoy wealth in their twilight years if they completed a term of service in the military.

8 Free Entertainment

In the modern world, we think it’s natural to pay for our trips to the stadium or the cinema—how else would they be able to support themselves? In Roman times, however, access to shows, whether they were gladiator fights, theatrical performances, or chariot races, was nearly always free.[3] Instead, shows were sponsored by wealthy patrons who were attempting to court the people’s favor. Most of the time, these hosts were aspiring politicians who wanted to get the people on their side. Occasionally, they went even further and sponsored the construction of new public buildings. The most extreme example of this was the construction of the Flavian Amphitheatre, commonly known as the Colosseum. Shortly after his succession, Emperor Vespasian began construction of the amphitheater on the old site of Nero’s personal palace, the ultimate symbol of an emperor granting a gift to his people. In return for sponsoring the games, the patrons were allowed to host them, which included deciding whether gladiators would die or not at the end of a fight. They were also permitted to give speeches or have people speak on their behalf at breaks between the performances. But the key fact remained: No matter how poor you were, you could go to the show for free.

7 Fire And Police Force

In 7 BC, Emperor Augustus decided to reform the way the city of Rome was organized.[4] He split the city into 14 wards and put them under the control of officials, whose job it was to oversee their portion of the city and ensure that things like crime, housing, and fires were kept in check. Premodern cities were massive fire risks, and large portions of them were frequently laid to waste by fires that spread out of control. After a particularly bad fire in AD 6, Emperor Augustus finally decided to create a public body responsible for the safety of the city—the vigiles. Made up of seven cohorts of 1,000 men each, the vigiles fulfilled the roles that modern police and fire departments serve today. Each cohort was responsible for monitoring two of the city’s wards. In many ways, there was little to separate the vigiles from regular soldiers. They lived in barracks and were expected to commit their lives to the job. They were also responsible for policing the city day and night and generally keeping order, including tracking down and returning runaway slaves. The vigiles had plenty of specialist equipment, including buckets, hooks for pulling down burning roof material, water pumps, axes, and a chemical compound called acetum, which they used to extinguish fires. They even had a fire engine—a horse-drawn cart with a double-action pump.

6 Free Baths

Baths, much like public entertainment facilities, were free to access—most of the time.[5] During the reign of Diocletian, the entrance fee was just two bronze pennies, and access was free on public and religious holidays. So they were much cheaper than a modern-day gym membership, and a Roman bathhouse contained many of the same features: a swimming pool, a sauna, an exercise room, changing facilities, massage rooms, and exercise rooms. In many ways, bathhouses served the same role as community centers do in cities today. They were hives of activity, where friends would go to have fun, politicians would go to preach their cause and win support, and pickpockets would go to steal the belongings of the bathers. Notches found in the walls of Roman bathhouses seem to have been storage for scrolls, so baths may even have provided reading material for their patrons—a much more feasible idea in Roman times, when scrolls were made of animal skin and therefore wouldn’t have been as vulnerable to the moisture in the air. Most baths were surrounded by places where people could buy food and drink. So the average Roman going to the bathhouse in the afternoon could enjoy a night out with friends, a swim, reading material, and a meal for next to nothing. The only caveat was that public baths were often, unsurprisingly, very dirty, and many of the wealthy built their own private bathhouses that they and their friends could enjoy by themselves.

5 Insulae: Social Housing

A Roman text, known as the Regionary Catalogue, states that there were 44,850 insulae and 1,781 domus in Rome in AD 315.[6] Both were types of residence: A domus was an individual home that contained a single family unit, while an insula was a block of communal housing occupied by tenants. While many of these insulae were built by private landlords, it seems at least some were funded and built by the Roman government to accommodate the capital’s population boom—or were, at the very least, regulated by laws passed by the Senate. In many ways, these insulae were very modern: The bottom floor was made up of shops or workshops, while the floors above were private residences of between one and four rooms, accessed by a central staircase. Many of them had balconies. While most were four or five stories tall, and laws passed by the Senate restricted structures any taller than this, some stretched to as many as eight stories. The Roman cityscape was much taller than many of us realize, and a city of similar height wouldn’t develop until the early modern era. While the Roman state seems to have stopped short of providing free accommodation for the poor, it was certainly concerned by the dodgy construction standards some of these insulae were built to, and by the late Roman era, they were even being built out of an early form of concrete. While these Roman blocks of flats certainly didn’t provide the highest of living standards, they were constructed en masse and regulated and monitored by the government in a way that housing projects wouldn’t be again until after 1500.

4 Free Water And Toilets

Ancient Rome, much like modern cities today, provided free public toilets and water fountains for their population.[7] However, a Roman public toilet wouldn’t meet the standards of many of us these days: A public toilet was a single room, with lavatories around the side walls that emptied into a sewer (sometimes) or a pit. There was no privacy, and anyone who used the toilet would have to use the sponge on a stick that everyone else used. Roman toilets did, however, contain running water fed by an aqueduct—and they were free to access. Public toilets wouldn’t exist again in cities for at least another millennium. Far more important, though, was the provision of free, fresh, and clean water in fountains. In his De Aquaductu, written around AD 100, Frontinus states that the nine aqueducts that fed Rome its clean water supply fed 591 fountains across the city with enough water to satisfy 900 people each. This wasn’t just the case in Rome; in Pompeii and many other Roman cities, water collection points were regularly spaced across the city. For most Roman people, a fresh supply of free, clean water was less than 46 meters (150 ft) away—a better ratio than many modern cities!

3 Free Health Care/Subsidized Doctors

In ancient Greece, like many places in the ancient world, health was considered a personal matter that people dealt with alone. If they were rich enough, they could pay for access to a consultant or a doctor. For many people, though, the best medical treatment they’d have access to would be common home remedies or family medical knowledge.[8] In Rome, however, times were changing. Rome’s first public hospital was built in 293 BC on Tiber Island, using Senate funds. Though hospitals were uncommon across the empire, they were always free to access and built using government funds—often from the purse of the local magistrate. Running costs were often subsidized by donations from people who used the hospital, or wealthy philanthropists. Much more common, though, were private doctors who ran their own practice (clinicus). Many of these doctors received a salary from the Roman government and used an unusual method of charging patients by increasing the price depending on the assets of the patient. For the very poorest, diagnosis and prescription were very cheap, though treatment was never actually free.

2 Collegia: Social Clubs

In the days of the Roman Republic, almost anyone could form a club, or collegium. All it took was three individuals who agreed to form it.[9] These groups were very important in everyday society, essentially operating like guilds did in medieval times. Groups of people from the same craft would come together and pool their resources, putting money into a collective pot that would work in a similar way to insurance if any of the group members fell ill, died, or lost their house. A collegium was like a modern-day corporation, social club, and political party rolled into one. Some collegia, like the example described above, were a kind of social security system for individual traders. Others, however, would have been business or trade ventures, while some clearly existed to support a certain political candidate or to express a certain political view in organized action. Since any three free individuals could form a collegium, they quickly became popular with the poorer people in society to lobby for political action. These kinds of collegia became increasingly common, until they were seen as a significant threat to the state. When the republic gave way to the empire after the rise of Julius Caesar, one of his first acts was to strictly limit people’s ability to form new collegia, making them have to personally get permission from the emperor rather than just the consent of two other people. Collegia largely disappear from history at this point.

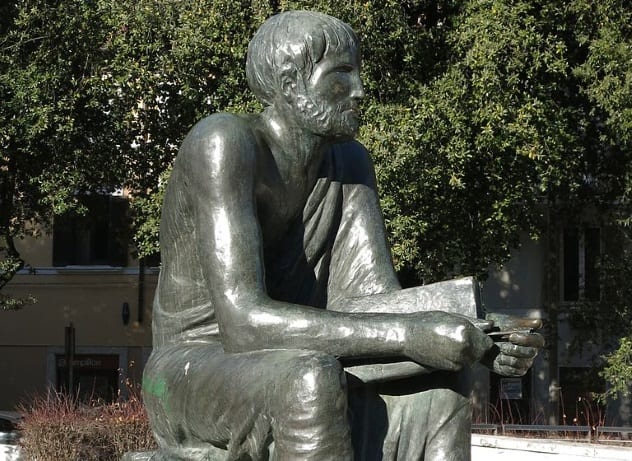

1 Natural Theory Of Disease

In 36 BC, Roman writer and scholar Marcus Varro wrote that new buildings shouldn’t be built close to swamps because of the risk posed by minute creatures that couldn’t be seen by the eye, which enter the body through the nose and mouth and cause serious illness.[10] While this idea was far from mainstream in Roman society, most Romans subscribed to a natural theory of disease rather than a divine one. Most commonly, they believed bad smells could be the cause of disease, as could having an imbalance of fluids (called humors) in the body. Marcus Varro’s statement was the closest they came to discovering the existence of germs—but their theories about how to avoid illness were largely accurate: Keep fit, rest when ill, drink clean water, don’t camp in one spot for too long, avoid moist environments, and clean yourself regularly.