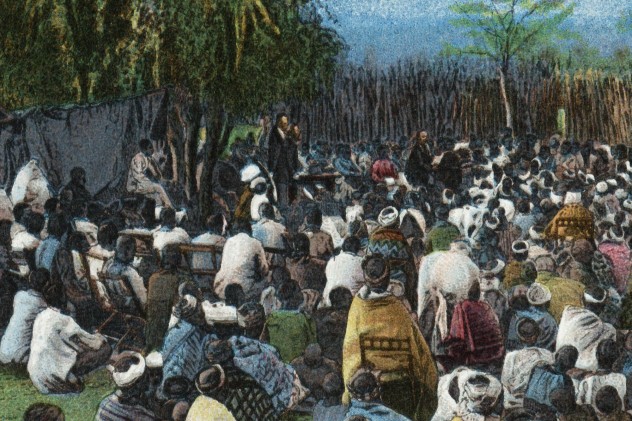

10 John Smith

Reverend John Smith was a member of the London Missionary Society living in Guyana in the early 1800s. It wasn’t a pleasant time by any stretch of the imagination; as the price of sugar dropped, plantation owners needed to make up the difference by forcing their slaves to work even longer hours under even more grueling conditions than they had previously been subjected to. Even though there were appeals in place to improve working and living conditions for the slaves laboring in British territories, decisions on the ruling were frequently pushed back. For his part, Smith was well-known throughout Demerara for advising the slaves to uphold the values of their newly adopted religion. He preached hard work and dedication to family, but plantation owners made it increasingly difficult to balance grueling work and family values. In 1823, a massive rebellion broke out in the colony. Between 9,000 and 30,000 slaves rebelled in a hugely unsuccessful revolt that was put to an end by the local military. Hundreds of slaves were killed, and Smith was arrested for his rumored role in organizing and encouraging the rebellion. It took several months, but word of the rebellion and Smith’s arrest reached England, where there were people willing to speak out on behalf of the missionary. Back in Demerara, Smith was tried and convicted. Even though he was given a reprieve from his death sentence, he died in prison from consumption. When the truth of his teachings came out, he was styled the Demerara Martyr for his attempts at encouraging hard work and responsibility over outright rebellion. His death shed a new light not only on the unreasonably hard life plantation slaves were forced to live, but also the politics and policies of the plantation owners in charge.

9 The Maryknoll Sisters

In a letter written to her sister not long before her horrifying death in 1980, Sister Ita Ford wrote, “Actually, what I’ve learned here is that death is not the worst evil. We look death in the face every day. But the cause of the death is evil. That’s what we have to wrestle and fight against.” On December 2, 1980, missionaries Maura Clarke, Ita Ford, and Dorothy Kazel flew into a Maryknoll conference in El Salvador, a nation on the brink of civil war. They met with another missionary, Jean Donovan, and left the airport. They hadn’t gone far when they were stopped by members of El Salvador’s National Guard who beat, raped, murdered, and buried them in a shallow grave alongside the road. The reaction to their deaths was nothing short of outrage. The missionaries had spent years working with the poor in Nicaragua before heading to El Salvador, where they found similar conditions. Their work was done largely with the financial backing and military training of the United States government. It was only in 2013 that the court battle finally came to an end; it was ruled that the general at the head of the military who killed the four missionaries—along with 70,000 others—would be deported back to El Salvador. General Vides Casanova was found to be responsible for the actions of his men in the brutal murders of the four women. Additionally, he had taken no action in response to any other instance of human rights violations that his men perpetrated. And there were a lot of human rights violations, which were made possible in part by the United States. In order to help El Salvador put down the rebellion of armed guerrillas, the United States provided financial backing, military training, and equipment to Casanova’s government. The murder of the four women brought American involvement in the civil war to the attention of the entire world.

8 Juan De Zumarraga

Appointed the first bishop of Mexico in 1527, Juan de Zumarraga arrived in Mexico bearing the title of Protector of Indians just after Cortes left the New World. What he found was the chaos left behind by the explorer; the native people had been persecuted, enslaved, and tortured. De Zumarraga took his title very, very seriously. He was one of the first to struggle to uphold the rights of the native people of the New World. His fellow officials, though, had a less benevolent attitude, and it was only by smuggling a message in a cake of wax that he was finally able to get word back to Spain about the atrocities that had been committed in Mexico. Finally backed by Spain, de Zumarraga became such an influential representative of the Spanish court that he oversaw the baptism of countless people and converted them from a polygamous to a monogamous society. Eventually, his worked helped to establish laws against taking native people as slaves. He went on to establish some of the first schools and hospitals in Mexico. His popularity in Mexico also led to the development of one of the world’s great commodities as we know it today: chocolate. Chocolate in its raw form didn’t appealed to Europeans in the New World at all. A group of nuns in Oaxaca stumbled into the idea of mixing it with sugar to make it more palatable for their bishop.

7 Dianna Ortiz

In 1989, Ursuline nun Dianna Ortiz was working with the residents of a number of small villages throughout Guatemala when she began receiving threatening letters insisting that she was working with “subversives” and that she was in danger. On November 2, she was kidnapped, held hostage, and tortured for information about the “subversives” the letters referred to. One of the men who kidnapped her wore the uniform of a policeman. After their interrogations failed, her kidnappers attempted to move her. She fled from the car while they were stopped in traffic and left the country within 48 hours. Her case was taken to some of the highest authorities in the United States. Over the next few years, the case exposed a variety of human rights violations that were going on in Guatemala. Returning to Guatemala, Ortiz faced hours and hours of interrogation by government officials who attempted to punch some serious holes in her case; they even went so far as to cite her nervousness during interviews as evidence that she was lying. Eventually, the Guatemalan government was found guilty of violating a massive number of international laws regarding human rights in their treatment of the missionary during and after the attack. Ortiz continues her outreach and missionary work today. June 26 has been declared United Nations International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, recognizing and supporting the victims and survivors of torture. Ortiz has also founded the TASSC, the Torture Abolition and Survivors Support Coalition, an organization that strives to put an end to episodes like the horrific ordeal that she endured and support survivors and their families through what is often a long and painful recovery process.

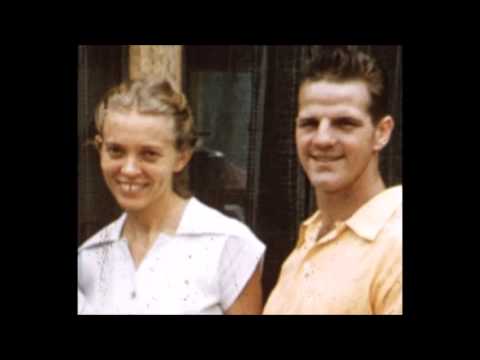

6 Elisabeth And Jim Elliot

In 1956, missionaries Elisabeth and Jim Elliot were in Ecuador, reaching out to one of the most remote tribes on record. No one had yet returned from attempting to contact the Auca. Jim, along with four other missionaries, attempted to do what no one else had successfully done. After meeting with three representatives, the missionaries were speared and killed. Elisabeth remained in Ecuador with her 10-month-old daughter. She had been working with the Quichua. A year after the death of her husband, Elisabeth was introduced to two Auca women; the introduction opened a door that had never been opened before and began a year-long relationship with the two women. Eventually, Elisabeth entered the world of the men who had killed her husband and colleagues, reassured by the women that she wouldn’t be killed like her husband because she was their friend. After living with them for two years, during which she converted a number of the Auca as well as the men who had killed the missionaries, she returned to the United States to become a speaker and author. Elisabeth has spoken about an incredibly wide range of topics. In each one of her speeches, her message comes from her heart and from the life she’s lived. She’s spoken of facing grief and death. She’s also promoted the idea that women should be subservient to their husbands and stay home to raise their children.

5 Bernabe Cobo

Spanish Jesuit missionary Father Bernabe Cobo arrived in Peru in 1599. Throughout his first decade in South America, he walked across much of the country. Along the way, he started what would become a lifelong fascination with the Inca. He wrote and left behind some of the most complete works about Incan civilization that we have today. After spending time in Lake Titicaca with the native people, Cobo learned their language, customs, and history as much as he shared his own. He wrote Historia del Nuevo Mundo only four years before he died in 1657. The work would ultimately contain 43 books, and even though some of it has been lost over the centuries, the 17 books that we do have provide a fascinating look into Incan life. He recorded—in amazing detail—stories of Incan deities and related their creation myths. The books tell the stories of Incan rites, rituals, festivals, and holidays. They even report the roles that their holy men held in their society. Cobo wrote about how nature guided their lives and their rituals, and how respect for the gods is worked into their everyday lives, from their farming schedules to their sacrifices. Thanks to his work, we also know an extraordinary amount about their daily lives, like their style of weaving, what their clothes looked like, and the methods they used to build walls and raise crops. Some of his information was gathered from other published sources about the Inca, but much of it he got simply by talking to the people around him. He interviewed the descendants of formerly powerful families. Much of it needs to be looked at through the eyes of the writer; his work isn’t a straight history of the Inca, and he often refers to some of their folklore in terms of his own beliefs. Still, he was responsible for putting together the most complete picture of the people that we have. Tragically, much of his work remains lost.

4 Allen Gardiner

English missionary Allen Gardiner’s life is a story of hope and optimism in the face of tragedy. Born in 1764, Gardiner lost his first wife early after they had been traveling through South Africa on a mission to bring Christianity to the Zulus. After remarrying, he turned his attention to South America. Starting in Buenos Aires and undertaking a staggering 1,600-kilometer (1,000 mi) journey through the wilderness and difficult terrain of South America, Gardiner was constantly faced with native people who weren’t the least bit interested in what he had to say. In 1842, he established the Patagonian Missionary Society and was still met with failure after failure to convert the natives. His last mission was to introduce Christianity to a people who Charles Darwin had declared “the lowest examples of the human race,” those living on the Tierra del Fuego archipelago. The mission left England well-equipped, but they found the natives were less interested in listening to them and more interested in stealing their supplies. Food and fresh water began to run out, they were plagued with bad weather and exhaustion, and the party began to die off. Later, Gardiner’s diary was recovered from the ruins of their camp. They had been waiting for reinforcements, but by the time fresh supplies came, it was too late. Facing death and starvation for himself and his men, Gardiner wrote, “If I faint or die here, I beg of you, oh Lord, that you would lift up others and send more workers to this great harvest field.” And more missionaries were sent. The Patagonian Missionary Society became the Society of Anglican Missionaries and Senders and currently has missionaries operating throughout South America and Africa. They actively take on a variety of issues, from establishing churches and schools to helping combat human trafficking.

3 Jose De Anchieta

Born in the Canary Islands, Jose de Anchieta was one of the first Jesuit missionaries to travel to Brazil after it was claimed by Portuguese explorers. Canonized in 2014 for his work in creating one of the largest Christian countries in the world, he’s perhaps most well-known as one of the founders of both Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. De Anchieta and the Jesuit missionaries he was working with did more than just bring Christianity to the new Portuguese colony; they changed the way people were living for the better. Like other missionaries of the time, they were left to pick up the pieces that explorers and conquerors left behind. They began legitimizing marriages between the first of the colonists and their native wives, and they held priests already settled there to a higher standard, making it clear that taking native people as slaves and concubines would not be tolerated. Part of the difficulty faced by early missionaries was the language barrier. De Anchieta was a natural with languages, soon mastering the native tongue. It was a necessary step in getting the native people to abandon one of their traditional practices: cannibalism. Bringing peace to the native tribes—whose bellicose nature led to the capture and cannibalism of other neighboring peoples—was also crucial. De Anchieta was taken prisoner by one group and held for five months. During his captivity, the story goes, he composed a poem to the Virgin Mary and only transcribed the nearly 4,200 lines from memory once he was released.

2 Gabriel Malagrida

Italian-born Jesuit missionary Gabriel Malagrida served several missions in Brazil. He was summoned to Lisbon, Portugal in 1753 by the queen dowager. It was in Lisbon that things went very, very badly for Malagrida—and for the rest of the Jesuit ministers. The king, Joseph I, was returning from an evening with his mistress when he was attacked. Wounded but still alive, the king was soon surrounded by the fallout of a plot by the Tavora family to put one of their allies on the throne. Malagrida had the misfortune of being the Tavoras’ confessor and was soon deemed a traitor. Malagrida’s position was used by enemies of the Jesuits to create a political campaign against them. The episode completely succeeded in supporting a political movement to undermine all the work the missionaries had been doing in Portuguese colonies overseas; they were accused of using their influence to turn Portuguese territory into an independent state. Malagrida’s accused transgressions were seen as confirmation of the Jesuits’ betrayal of their royal family. Accused of convincing the converted natives to rebel against their colonial masters, the Jesuits suddenly found themselves opposed at every turn by the state and the political machine. In 1758, an official investigation was conducted into the Jesuits’ activities in South America. Malagrida was executed in 1759, and the Portuguese effectively stopped all Jesuit activity.

1 Bartolome De Las Casas

Born in Spain in 1484, Bartolome de las Casas’s interest in foreign lands began when he was present at a parade through Seville honoring Christopher Columbus. By 1502, he had made his first trip to the Americas, spending five years in Santo Domingo and witnessing the brutal treatment of the native people there. By the time his work had endowed him with enough authority to be heard in the Spanish court, it was under the control of Charles I. In the New World, the Spanish had already enslaved a huge amount of the native population in their search for gold and cheap labor. De las Casas re-established the idea of small towns for the native people. In these towns, they would be free to live and work for themselves. Presenting his idea for the re-colonization of Hispanola, de las Casas won the support of the king, but it wasn’t as easy to convince those living an ocean away. He took the knowledge that he’d gathered so far and headed to other areas. Throughout his ministry, he spent time in Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. During his travels, he compiled a huge amount of information about native cultures, writing his Historia General de las Indias and providing us with much of the information we have today on pre-colonial Central America. He also established what was at the time a revolutionary idea: the spread of the Church’s teachings not only by peaceful means, but by means that respected the native culture and the people who practiced it. Las Casas spoke out against slavery, stating that it was so incredibly immoral that it needed to be stopped. Strangely, he was almost all right with the enslavement of individuals from Africa. He suggested at one point that slaves from Africa should be used to replace the slaves from America and requested that his trips to the Americas be accompanied by groups of slaves. That position didn’t last long. Clearly bothered by the idea of simply trading one group of slaves for another, he looked deeper into the trade in the late 1540s. Once he witnessed the atrocities committed against African natives, he began campaigning for the abolition of slavery in both lands, a revolutionary idea at the time. Read More: Twitter