It’s also what the list author grew up on, and makes for some mighty tasting eating… somehow retaining a recognizable and homogeneous Taste of the South in spite of its disparate origins. For the purposes of this list, the South is defined as north of the Gulf of Mexico’s northern coast, west of the Altantic Ocean, south of the Mason-Dixon line, and east of the western Arkansas border (suck it, Texas and most of Florida). Some of the foods are prepared, end-product dishes and some are base ingredients (foodstuffs). We aren’t that big on distinction in the South; it’s either Southern or it’s not — it either tastes good or it doesn’t — we either cook it often or we don’t. ‘Nuff said.

Right off the bat there is certain to be controversy, because of the inclusion of two completely different Cajun dishes under the same heading that speaks of a Trinity while otherwise ignoring an entire genre. It happens to be true that a good list of Southern food must include Cajun cuisine… yet the author is not from anywhere near New Orleans, and Cajun food has never been a staple. Anyway, Jambalya is a paella-like rice-based dish with French, Spanish, and Carribean influences — and its variations are endless, especially when it comes to what vegetables are used. Most often it does include what are known as the “trinity” of Cajun cooking — onions, celery and green peppers, made famous by that blustering idiot Emeril. Stock of some sort is used to get “wet” rice, often approaching a risotto in texture. The most typical meats used are Andouille sausage (a quite spicy Cajun variety) and/or shrimp. Gumbo, on the other hand, is essentially a thick (but not “beefy”) stew. Again, it almost always includes the trinity of onions, celery, and green peppers… hence the list entry. When most people think of gumbo, they think of okra, a highly nutritious vegetable brought over from Africa during the slave trade. Gumbo does not have to include okra, but it will certainly be mucilaginous to a greater degree if it does. Accomplished chefs can use immature okra pods, cut thickly with VERY sharp knives, and not stir the stew much, thus decreasing the amount of okra slime that interacts with the stock. Other people, when hearing the word “gumbo,” often think of “file gumbo.” File is mainly dried and powdered sassafras leaves, used as a flavoring and thickener. Sassafras has a unique flavor that is instantly recognizable to anyone who has tried it; sassafras can be overpowering as a spice even though it is not that intense in and of itself.

Sigh. We cannot leave New Orleans for a bit, but we’re on our way to Georgia. Legend has it that the French developed pecan pie after settling in Louisiana and introducing the tree to the natives. However, the Southern pecan pie will forever be inextricably linked to the introduction of Karo syrup in 1902. More importantly, in the early 1930s, a wife of a Karo executive made a pecan pie with the almost sickenly-sweet corn syrup and the company publicized it. In many parts of the pecan-growing South, such as Georgia, people just say they made a “Karo pie” and everyone knows it’s a pecan pie made with Karo syrup. If made right, Southern Pecan Pie will only be palatable to those with a serious sweet tooth.

Ah, we can now talk about new influences. First, “cobblers” were made in England long before the Pilgrims decided to take their religion and go elsewhere. But the ingredients were different, with the British version typically featuring meats. Also, many sources will state that “cobbler is a western U.S. cuisine innovation, made necessary by ubiquitous Dutch oven cooking during the opening of the American West. It is unlikely that they predated the cobblers of such previously settled places as the Carolinas though, given the preponderance of readily available ingredients. For the purposes of this list, a Southern cobbler must feature what might be called an “interior dumpling” — as amply demonstrated by the image, a Southern cobbler has a doughy substance within its middle. There is a biscuit-like crust, and there may or may not be a bottom crust. If there is, no attempt will be made to make it flaky. The English version, even when made with fruit, typically aims to keep the crust totally separate from the filling — as is also true in some northern U.S. pretenders to the throne. Southern cobblers don’t care about that and just come out as a doughy-crusty-fruity-sugary whole.

Author ruefully admits that this classic should probably be ranked much higher, perhaps in the top five, only it segues so perfectly from talk of cobblers. That’s because the concept of wet-dough-within-the-food applies, even though this is a salty meat dish rather than a sweet fruit dish. People have been making dumplings basically as long as they have had a grain to grind for flour and liquid with which to form a dough. And chickens certainly did not originate in the American South. How then, has chicken and dumplings come to be so identified with Southern cooking? It is possible that no one knows for sure. However, truly Southern chicken and dumplings will be a thickened stew-like dish, with interior (not just on top) dumplings that are fairly close to a non-sweet “wet” dough as in a cobbler. The taste is utterly different, of course, but the science is relatively close. If you ever experience a biscuit-like crunchiness in a bowl of chicken and dumplings, sorry, but that is not what has propelled real Southern c&d to a pedestal far taller than similar dishes in many other cuisines over the centuries. The primary flavor signatures should be chicken fat with salt and pepper to taste..

It is the adoption of a food, not its origination, which controls definition of food cultures. And the tomato had to cross the ocean twice before the American South finally fell in love with this summer staple of home veggie gardens. Native to the Andes, Spanish conquistadores took it back to the Old World. We all know that southern Italians took to the tomato quite well, but it was Spanish and French influences coming back across the Atlantic that established the oft-reviled plant in the South. And certainly the long, hot summers of the American South are perfect for this fruit-like vegetable. Southern cooking regarding the tomato is unique in that it is not used all that often an an ingredient (some forms of BBQ or soups excepted), but rather as a dish unto itself. Very easy to grow, generations of Southerners have discovered the joy of simply placing a thick slice of vine-ripe tomato on a plate next to a sandwich during summer. The slice is usually salted, often heavily. But the most original Southern contribution to the uses of the ubiquitous red orb isn’t even red: Fried Green Tomatoes. Archetypal enough to become the title of a movie set in the South, this dish lends verisimmilitude to the fact that only the Scots rival southern Americans in frying foods. FGTs are always pan-fried, not deep-fried. There may or may not be a binder wash of egg & buttermilk, and the coating is either corn meal, flour, or a combination of the two. Note: this is also the most common way Southern cooks utilize eggplant — an aunt’s recipe for both FGTs and Fried Eggplant often differs only in the main ingredient. Special mention is now made of another crop that flourishes under specific Southern growing conditions: the Vidalia onion. By law — both state and federal — an onion cannot be sold as a “Vidalia” unless it it grown in a VERY specific region in Georgia near the town of Valdalia. The laws literally define the boundaries by a bewilderment of county roads. And that’s because the sandy, very-low-sulphur soil in that area produces an onion of exceptional sweetness and low “bite.” A properly grown and stored Vidalia is mild enough for the majority of people to eat as unadorned raw slices. They are planted in the fall, grow throughout the winter, and then storehoused until just the right time — hitting East Coast markets in early April as a welcome celebration of spring.

Drive the byways of many medium-sized towns in the South, and you will encounter “catfish joints” just like the more common BBQ joints. You can be absolutely certain that EVERY catfish joint will serve hush puppies. Several religious dietary restrictions will preclude a number of people (most notably, observant Jews) from enjoying this classic Southern combination because the catfish feeds on bottom and has no scales. But its meat is firm, white, and sweet. Perfect for breading up and deep-frying. Almost all of the rivers of the South contain channel catfish, and that is the species most commonly served. In restaurants nowadays, though, you are most likely to be served farm-raised catfish, as that fish is the leading aquaculture industry in the United States. Four Southern states — MS, LA, AR, and AL — account for 94% of the production (source: Mississippi State University Extension Service, 2003 statistics). And as long as you are deep-frying, make some hush puppies. There are as many hush puppy recipes as there are hush puppy cooks, but you simply must start with corn meal… and if you keep reading this list, you’ll come to realize that true southern cooks always keep corn meal on hand — usually within easy reach in the cannister set. From the starting point of corn meal, other dry or dryish ingredients are added: some flour maybe, usually some onions or onion flavoring; many recipes call for whole kernel corn and/or sugar. Then liquid (milk, eggs, water, beer are common) is added to form a batter. The batter is scooped into balls and deep-fried. The author believes that a good hush puppy will not be dry and crumbly on the inside; it should have a rich, almost caky consistency while the outside should of course be Golden Brown And Delicious.

A single “named” stew scores high on this list because it is so Southern that many other cultures would not even contemplate making it. If you have had Brunswick stew, the chances are extremely high that you have never had the “real” version, unless you are from the South — and maybe not even then. That is because the good stuff is made with the meat of the grey squirrel. It is impossible to discuss this dish without discussing the ubiquitous squirrel. It may be a rodent, but its meat is velvety in texture, flavorable, and as lean as you can get. It tastes like squirrel. But, squirrels which have been feeding off of pine sources are considered very inferior throughout the South, as are fox squirrels that are not feeding almost exclusively on corn. The good old American oak-and-hickory-feeding grey squirrel shines in this stew, which is further distinguished from other stews in its reliability on generous numbers of corn kernels simmered for a long time. Did it originate in Brunswick County, Virginia or the town of Brunswick, Georgia? Or even Brunswick County, North Carolina? Regardless, it’s a true Southern fall classic of harvest season combined with squirrel season, though nowadays most people make it with chicken or pork (as in the image)… more’s the pity. And we will in passing dismiss (without ranking) another uniquely Southern stew, known as “burgoo” and being the main draw at more than one cooking festival, especially in Kentucky. Typically heavily spiced, it could almost be defined as a chili using chicken, mutton, or other whitish meats rather than beef. Most winning burgoos are “thin” in character and quite bold in their spiciness. Note: burgoo is subject to many spelling variations, and is both identifiable yet different from bowl to bowl as is chili.

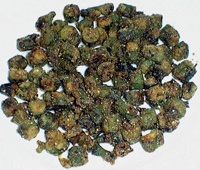

Many people are aware of the contributions of the former slave turned agronomist, George Washington Carver, to the uses of the peanut. Fewer are aware that he never came up with peanut butter, a food that can only be defined as “American without regionalism” because its development history ranges from Battle Creek, Michigan by famed health-food guru John Harvey Kellogg to the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair to becoming an early national-distribution item, once shelf-stability was solved by J.R. Rosefield in California in 1922. Southerners, however, grow lots and lots of peanuts and use them for many purposes, including food for world-quality hams and the only-in-the-South Boiled Peanuts pictured in the image (a dish truly hated by the list author). Thomas Jefferson was an early adherent, experimenting with the legume in Virginia. Commonly called “goobers” in some states, a drive through the state of Georgia is almost guaranteed to pass large commercial peanut farming operations. And of course, it is common knowledge that former president Jimmy Carter was a Georgia peanut farmer before entering politics (though few remember that by education he was a nuclear physicist who pursued a career in the U.S.’s “nuclear navy” prior to his father’s death).

“Greens” are the leafy parts of numerous plants. The quintessential “greens” of Southern cooking is collard greens, a type of loose-leaf cabbage similar to kale. But many other greens are used, including kale, turnip, spinach, mustard, and that no-one-else-eats-it green, the leaves of the poke plant. A popular song of 1969, “Poke Salad Annie” by Tony Joe White, has led to the erroneous belief that Southerners eat poke leaves raw in salads. Not true, as uncooked pokeweed leaves are extremely bitter and possibly toxic. The confusion arises from the Old English term “sallet” or “salit” which refers to boiling and discarding initial waters to remove bitterness. “Greens” are a staple of Southern Soul Food, having been a food of necessity for black slaves and poor blacks after the Civil War. The dish is usually flavored with bits of fatty, salty meat such as fatback from a hog. In many grocery stores throughout the South in modern times, fatback is sold (at a per-pound price comparable to what the average consumer would consider not cheap for “desirable” hog products) almost exclusively for use as a flavoring agent. The process of cooking genuine Southern greens is basically simple, being that of stewing freshly washed greens with seasonings and some fatty meat, but of course everyone has their particular take on it. An initial water may or may not be discarded, based on the bitterness of the greens used and how much of said bitterness the cook wants to retain. Regardless, the final remaining water — which stews the longest– is reserved and known as “pot likker” and often sopped up with cornbread (which see).

Corn is a New World food that is now grown all around the world; more total tons of it are now produced than are of either wheat or rice [source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2006 statistics]. And while the northern states also have several varieties of “cornbread” made from corn meal, they are nowhere near as famed as those of the South — mainly because they are also nowhere near as good. Cornbread may be baked or fried (or a combination of the two), but for authenticity the cooking vessel must be a cast-iron skillet… one that has been in use a long time and is thus properly “seasoned.” It is more than possible to see cornbread served at any southern dinner (in some homes, at every dinner!), but it is often paired with one of three signature accompaniments: black-eyed peas or pinto beans, a bowl of greens (which see), or crumbled into a glass of cold buttermilk and eaten with a spoon.

If you have only tasted okra that was not fried, you must understand that the stuff becomes literally a whole different food when breaded and dropped into hot oil or fat. The truly amazing sliminess that so many people object to disappears entirely. And the unique “soft-green” flavor of the pods, something like a cross between avocado and zucchini with mild notes of thyme but better, fares extremely well with a good corn meal-based breading. Two images are provided because there are two schools of thought towards Southern fried okra. Both pictures are of okra that is perfectly cooked for its style. The darker one was panfried in a cast-iron skillet, using a fairly light dusting of just corn meal and salt. The second was deep-fried after using a buttermilk and egg wash as a binder, then coated with flour (note: more commonly, the dry coating will be about a 50-50 mix of corn meal and flour). The pan-fried okra has a crispy, almost crunchy mouthfeel and every single bit of sliminess has been cooked out of it; the overall taste will be homogeneous. The deep-fried okra will — bearing in mind it won’t be slimy — nonetheless have a wettish interior, and the taste will noticeably include separate notes of that interior, the pod fiber, and the breading. Restaurants will almost always serve the second type, because if you already have a deep fryer going, clean-up is much easier. The list author enjoys both types, with a slight prejudice towards pan-frying.

Another Old World introduction, from back in the days of the voyages of Columbus. Even with numerous dietary restrictions against it, more pork is consumed worldwide than any other meat (source: National Food Review). And the South certainly downs it share: from the snout to the tail, pigs are almost revered. And the world has embraced the exceptional quality of Southern hams. As Nero Wolfe author Rex Stout once had the famous sleuth declare, “Poles and Westphalians have the pigs, the scholarship, and the skill; what they do not have is peanuts.” Pigs fed peanuts during their growing lives do indeed produce a distinctively sweet ham. And although the famous hams of Smithfield, Virginia have been made since the town’s founding in 1752, a 1926 Virginia law amptly illustrates the importance of pairing swine with peanuts: “Genuine Smithfield hams [are those] cut from the carcasses of peanut-fed hogs, raised in the peanut-belt of the Commonwealth of Virginia or the State of North Carolina, and which are cured, treated, smoked, and processed in the town of Smithfield, in the Commonwealth of Virginia.” The peanut requirement was repealed in 1966, and most hams today are fed a corn-based high-protein scientific diet… too bad. There are two main types of hams: country and city. Southerners devour them both by the ton. Country ham is dry-cured and very salty. City ham is what you get from the deli. There are also combination curing methods. Regardless, “baking a ham” is a ubiquitous event in the South, and the varieties of “glazes” are endless, although pineapple and brown sugar are probably the most popular glaze ingredients.

Although almost every culture that has raised chickens has fried them, for many people the very term “fried chicken” conjures up visions of the South. The initial influence was probably immigrants from that previously-mentioned Frying Capitol, Scotland. But frying chickens southern-style undoubtedly owes its greatest debt to the slaves. Chickens represented an economic no-brainer to slave owners, as those in bondage could raise the birds themselves next to their quarters, providing them with eggs and meat with little or no additional capital outlay required. As is common to most foods on this list, it must be repeated once again: there are as many recipes as there are cooks. Both pan-frying and deep-frying have their adherents, but for pan-frying one needs that old and seasoned cast-iron skillet. Fried chicken came to be so associated with Southern culture that social mores developed around it. It was the quintessential Sunday dinner (an afternoon meal, not an evening one, yet the largest of the day) entree. It would be surprising if ANY church pot-luck dinner did not include fried chicken… giving rise to the idiom “disappearing faster than fried chicken at a pot-luck dinner.” Then, fried chicken really took off. The phenomenal success of the Kentucky Fried Chicken chain spawned dozens of competitors — virtually all of which came out of the South using Southern recipes. And even that could not stop fried chicken from becoming the most common home-cooked meal in the late 20th century, eaten more often than even hamburgers. That trend has declined; the author feels this is attributable to both the ease of take-out and the time required to prepare and clean up after a genuine home-cooked fried chicken dinner.

Let the, uh, fireworks begin! In the South, pork is barbeque, period. Along with the marrying of Mexican food into the cowboy trail tradition to create what is known as Tex-Mex or Southwestern cuisine, Texas’ insistence on using beef (which is what they had, after all) for its barbeque is why that state is NOT represented on this list. Hog-pickin’ goes way back in the true South, and was even a super-popular way for politicians to try and impress the voters as far back as the 1700s: they had pit masters cook a hog or two, and broke out the whiskey. Barbeque itself traces its roots to the Carribean, where indigenous people impressed white explorers by smoking meats over a wooden rack called a barbacoa. But again, it was African-Americans who turned pig, woodsmoke, and time into phenomenal succulence. It could be said that barbeque, (along with WWII overseas service), greatly helped to integrate Southern society… at a time when whites were loathe to drink from the same water fountains as blacks, they cheerfully bellied up to the cinderblock ‘que joints run by black pit masters who were masters indeed. But we cannot get away from controversy, even across so arbitrary a boundary as an adjoining county line. The image shown is North Carolina pulled pork barbeque — specifically, Eastern North Carolina. There (and in hundreds of places nationwide serving this style), the sauce is very thin, vinegar-based, with red pepper flakes and very little else. To the uninitiated, the meat appears not to be sauced at all — just seems to have a wettish sheen and a few flakes of red. But rest assured, it will have a bite to it. Travel just a little bit to the west, however, and in the same state the same pulled pork shoulder — perhaps even cooked with the same dry rub and in the same manner — will be doused with an obvious red sauce using tomatoes and/or ketchup. While the list author definitely prefers the Eastern NC style, he points to the fact that if you buy a “Carolina style pulled pork sandwich” at a joint IN ANOTHER STATE, you will likely be served the Eastern style, and thus that style must be considered more “archetypal” for the purposes of this list. Of course, pulled pork is only one dish in the Southern pork barbeque pantheon. “Going whole hog” is the phrase of art denoting the all-day process of barbequing an entire pig to feed many people at once. Both an art and a science, it represents an awesome undertaking and responsibility for Southern pit masters, as there is no recourse should either the art or science fail. Also, those who aren’t pulled pork freaks usually think of ribs when they hear the word “barbeque.” And they are indeed good. But when sampling the food of an unknown ‘que joint, one should probably start off with a pulled pork sandwich. If they can’t do that well, it doesn’t bode well for other pig parts. Ultimately, though… we’re talking swine here, not beef or poultry.

No one really owns a claim to either biscuits or gravy. Biscuits are a type of baked, leavened bread. Gravy is officially a “sauce,” albeit it usually a fairly thick one. The ingredients for both have been around for a long, long time. But the South invented the beaten biscuit, and using that 1850’s “technology,” America moved pell-mell into the realm of Bisquick-style mixes and canned grocery store doughs. Doesn’t matter. What matters is the pairing of a favored biscuit with sausage gravy as a hearty, belly-filling breakfast item — often the only course but no less hearty and filling therefore. First, let us mention and thus be rid of red-eye gravy, which is undoubtedly Southern but uses coffee as its base liquid. Enough of that. The archetypal biscuits and gravy from the South is a white sauce, using milk and/or cream. It can be made either from fat left from frying sausage or from a roux of butter and flour with sausage crumbles added later. But even though other types are certainly possible, what we are talking about MUST be a sauce for and/or from sausage. Pork sausage, of course. Using either pan drippings or a roux, all-purpose flour is cooked at least until no chalky taste remains, then liquid from a cow is stirred in to create a smooth and thick gravy. Salt and pepper, (plus the sausage flavor) are all that are required in terms of seasonings. The color of the gravy will vary by region and recipe. Generally, the longer the flour is cooked, the darker the color — and the “nuttier” as opposed to “creamier” the final taste will be. The list author does not like to see any shade of brown in gravy used for this purpose (other than sausage chunks), although a light grey as in the image is usually ok. World-class gravy makers will tell you that it’s a simple thing to do, with only a few ingredients and a couple of steps, but are uncomfortable in writing said down as a recipe… because in the final analysis, making gravy is a process rather than a recipe, and you have to stand there and make it “on the fly” as it were. Note that few words have been devoted to the biscuits. That’s on purpose. Barely acceptable biscuits and great gravy will be wonderful; great biscuits and barely acceptable gravy will be barely acceptable. There is absolutely nothing wrong with popping a can of store-bought biscuits and making an excellent gravy to slather over them; however, flaky-layer biscuits tend to yield poorer results than biscuits with unlayered centers. Contributor: grubthrower