Unusual burials and those abandoned where they died also bring historic questions to the living—sometimes mysterious, often heartbreaking. Then there are the bizarre things people did with the dead as well as amazing glimpses into lost lives.

10 A Medieval Female Criminal

In 2016, Bulgarian archaeologists discovered a necropolis in the city of Plovdiv. A year later, investigations progressed to a late medieval grave and the contents were unusual. The person inside had been placed facedown. Reports speculated that the remains most likely belonged to a bandit, especially since the skeleton’s wrists were tied behind his back. A better look at the skeleton has since proven that it was female. Though her history is lost, the strange position was almost certainly punishment for a transgression in life and not to prevent her from turning into a vampire. In the past, a spate of strange and gruesomely treated graves betrayed the ancient Bulgarians’ fear of the undead. Some were staked; others were thoroughly nailed down. But the woman, one of eight medieval graves found in the Nebet Tepe Fortress, had no such mutilations.[1] The rare burial was not the only noteworthy find. The same excavation also found evidence that human occupation at Plovdiv started as early as the fifth millennium BC.

9 Strange Status Symbols

Iron Age Scandinavians considered the goose the ultimate status symbol. Researchers reached this conclusion after peeking into several Nordic graves. If you lacked the rare bird (as geese were in Scandinavia at the time), a chicken in the tomb was an acceptable switch. The 2018 study cataloged content inside 100 graves from AD 1–375. This was a critical time when Nordic countries saw many cultural changes because of Roman influences. Scandinavia took to the Roman trend of burying animals with their dead. Women were typically buried with sheep, and one infant was interred with a decapitated piglet. Geese were sacred to the Romans. Thus, only the most privileged Danes took one along into the afterlife. One man’s tomb was royal, filled with a menagerie that included a goose, cattle, sheep, a pig, and a dog.[2] The latter proved that not all the animals were food for the dead. Cut marks on some species did suggest that Nordics adopted another funerary tradition from the Romans—to feast on the meat first. The dog had no cuts and probably symbolized friendship with a warrior master.

8 Turkish Mass Grave

The 3,000-year-old city of Parion started out as a Greek settlement and fell under Roman rule in 133 BC. Today, the ruins of this major harbor stand in Turkey. In 2011, archaeologists puttered about the site during an unofficial dig. It soon turned very official when a mass grave was unearthed. One child and 23 adults turned up. Unlike most mass graves, their burial was not the result of violence. On the contrary, the multi-tombed structure was lined with grave goods. In addition, the careful arrangement of the bodies suggested high status.[3] The dead were not interred all at once but over a long time, from the first to the third centuries AD. However, a grisly find appeared odd among all the signs of respectful funerals. The occupants of the tomb were decapitated. At one end of the mass grave, 15 skulls were recovered. The rest were eventually located in a northeast corner, together with the child.

7 Knives Made From Humans

During the 1800s and 1900s, missionaries reported a gruesome practice: The warriors of New Guinea used bone daggers sourced from humans. The weapons were used in close combat, reportedly to disable prisoners who were later served up as dinner. In 2018, researchers wanted to know why such a gory relic was a prized possession. As it turned out, human knives were practical and bestowed powerful rights upon the owner. Measuring up to 30 centimeters (12 in) long, these thighbones were not plucked from the leg of just any random person. They came from one’s father or an influential individual.[4] The dagger continued to hold the status and rights of the deceased, so the living person who possessed it could claim those privileges. It also turned out to be more resilient than another New Guinea knife crafted from the cassowary. The cassowary is large and flightless but remains one of the most lethal birds on Earth. Their thighbones made decent daggers. Unfortunately, they turned out flatter and lacked the fortifying curvature of human thighbones, making cassowary knives only half as strong. Additionally, bird bones were easier to find, which made human daggers more valued for their rarity.

6 A New Pompeii Child

Alone and scared, a Roman child fled from hot volcanic ash and debris in AD 79. The youngster decided to take shelter in the public baths building. But as Vesuvius erupted, its superheated pyroclastic cloud killed everyone who stayed behind in Pompeii—including the child. Citizens received a fair warning when the volcano smoked and rumbled for days. Even so, about 2,000 people chose to remain in the city. In 2018, sophisticated scans swept the bath complex. When the discovery inevitably happened, it was unexpected because the area had been considered fully explored since the 19th century. He or she was around 7–8 years old and became the first child to be recovered from the ruins in half a century. To determine the youngster’s gender and health, archaeologists removed the skeleton for future testing.[5] As to how exactly the child perished, he or she likely died of suffocation when the pyroclastic cloud sealed off the building. Located some distance away from Naples, Mount Vesuvius remains a danger today and had a major eruption as recently as 1944.

5 People With Extra Limbs

In 2018, archaeologists did a double take when they opened dozens of graves in Peru. Discovered in the town of Huanchaco, some skeletons had extra limbs. The 1,900-year-old individuals belonged to the enigmatic Viru people (AD 100–750). Why almost 30 of 54 burials included additional parts, especially one skeleton with two extra left legs, stumped the archaeologists. However, there was one disturbing clue—most were adults with traumatic injuries. These included blunt force trauma and slice marks. One theory suggests that the limbs were funerary sacrifices. However, for the moment, that idea is shelved with other unknown facts, such as the age and gender of the multi-limbed people and whether there existed any link between the deceased and donors.[6] Interestingly, the culture that followed the Viru, the Moche people, did the exact opposite. They often packed their dead away with missing limbs. When they did decide to include something extra, they added more than a single arm or leg. Usually, it was an entire sacrificial victim.

4 A Horse Surrounded By People

In 2011, a pyramid was found in Sudan. Nestled inside the ancient Nubian city of Tombos, the elite structure suggested that a very important person was buried inside. The complex had a chapel, and a shaft led to underground rooms. This architecture was known to be reserved for high-ranking humans. In fact, the remains of over 200 individuals lined the four chambers. However, in a surprise twist on most ancient burials, scientists realized that the tomb was meant for a horse and the people were secondary occupants.[7] The 3,000-year-old mare was found 1.6 meters (5 ft) down the shaft, surrounded by artifacts of status. Wrapped in a shroud, her color was still obvious. The chestnut horse died at age 12–15. The advanced age and elaborate grave indicated that the mare was important to her owner. She’s valuable for modern reasons as well. The animal is among the most intact horse skeletons from this period, and an iron piece, likely bridle-related, is the oldest iron in Africa. The monument also suggested that Nubian horses were more revered than history gave them credit for.

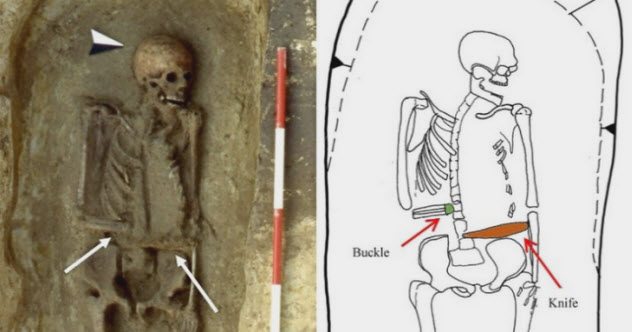

3 A Dangerous Amputee

From medieval Italy comes a really weird graveyard. Among the eternal human residents are greyhounds and even a headless horse. The showstopper was a man found in 2018. In life, the middle-aged guy had been an amputee. For reasons unknown, his right arm was severed at mid-forearm. Instead of causing vulnerability, one grave item suggested that he actually became more dangerous. He belonged to the warrior Longobard culture and, like most males in the cemetery, was buried with a knife. While the rest had their blades next to them, this man’s arm and knife was found on his chest. Their positions suggested that the weapon was a deadly prosthesis.[8] His body showed the wear and tear from regularly tying something down. The arm bones were deformed by pressure, dental damage was consistent with using the teeth to fasten straps, and his shoulder developed a ridge from keeping the arm in such a way that he could use his mouth. That the man survived the amputation in an era without antibiotics is remarkable. He lived for years afterward, a hat tip to one individual’s spunk and community compassion.

2 Sandby Borg Slaughter

During the fifth century, Sandby Borg prospered on the coast of Oland island near Sweden. When archaeologists finished a three-year dig in 2018, they left with a few horrors. The villagers had suffered a brutal end. Around 1,500 years ago, an enemy attacked and massacred people in their homes with shocking efficiency. The violence was exceptional. Nine bodies were found in one house. In another, an elderly man had been left to burn in a hearth. People were struck down in the streets. A tiny arm bone showed that not even babies were spared.[9] It is not clear who decided that Sandby Borg was no longer welcome, but the trauma ripple was so severe that nobody returned. The dead were left where they fell, valuable animals starved to death, and not even precious jewelry and gold could lure looters. So far, only three houses have been excavated and this patch produced 26 skeletons. Sandby Borg consists of about 50 more homes, and archaeologists expect the ancient death rate to climb, perhaps exponentially. The island had around 15 settlements, but only Sandby Borg was razed in this manner.

1 World’s Largest Child Massacre

When locals found bones on Peru’s northern coast, they alerted nearby archaeologists working on a temple. By 2016, all the skeletons were cleared. The scene was difficult to absorb. Around AD 1450, experienced killers dispatched 140 children and 200 baby llamas in what was likely history’s biggest child-killing ritual. The kids were buried facing the sea, and the llamas looked the other way, toward the Andes. All the victims had their faces smeared with red pigment. Bones were broken in a way that suggested their hearts were removed. Though human sacrifice was a fact of life during ancient Peru, such a mass event in the Chimu civilization is unheard-of. Genetic analysis showed that boys and girls, ages 5–14, were harvested from several ethnic backgrounds, sometimes from far away. The slaughter then went ahead near Chan Chan, the Chimu capital and one of the largest cities of its time. A mud layer near the bodies suggested that the ritual was an act of desperation, not bloodlust. The mud was linked to a destructive El Nino event that pushed the Chimu’s resources to the brink. When adult sacrifices did not stop the floods, they turned to more valuable victims—the children.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages