For example, we get angry and we want to tell people why their stupidity has made us mad. Usually, this is with well-chosen, colorful language and it doesn’t really change anything whether our words are in Sumerian or English. Some written evidence of anger has survived from some of our earliest civilizations. Language and writing, it turns out, are great inventions to express our disgust with our fellow man. Here are 10 angry letters that have survived history, ranging from irked to vein-bursting hatred.

10 Letters Between Pope Innocent IV And Guyuk Khan

These angry letters were sent beginning in March 1245 after an invasion of Russia and Eastern Europe by the Mongolians. Innocent’s letters to the khan were designed to convince him to stop the invasion of Christian lands or at least feel out the intentions of the conquerors and maybe even convert them to Christianity in the process: God has up to the present allowed various nations to fall before your face; for sometimes He refrains from chastising the proud in this world for the moment, for this reason, that if they neglect to humble themselves of their own accord He may not only no longer put off the punishment of their wickedness in this life but may also take greater vengeance in the world to come.[1] When Guyuk Khan responded, he frequently said of Pope Innocent’s requests, “I have not understood.” In other words, “What on earth are you talking about?” He also said: How do you think you know whom God will absolve and in whose favor He will exercise His mercy? How do you think you know that you dare to express such an opinion? Through the power of God, all empires from the rising of the Sun to its setting have been given to us and we own them. How could anyone achieve anything except by God’s order? Since both parties considered themselves to be the appointed representative of God, neither was convinced by the other’s ultimatum. In short, both of these upset rulers thought they were right.

9 Letters Between Frederick I And Saladin

Frederick I (aka Frederick Barbarossa) had heard that a new Muslim leader named Saladin was marching on Jerusalem. So Frederick sent this letter threatening Saladin not to proceed: We can scarcely believe that you are ignorant of that which all antiquity and the writings of the ancients testify that innumerable countries have been subject to our sway? All this is well-known to those kings in whose blood the Roman sword has so often steeped: and you, God willing, shall learn by experience the might of our victorious eagles, and be made acquainted with our troops of many nations.[2] Frederick then listed a number of different armies under his command. By the time the letter reached Saladin, he had already been the conqueror of Jerusalem for three months. He replied: We make it known to the sincere and powerful king, our great and amicable friend, the king of Germany, that a certain man called Henry came to us professing to be your envoy, and he gave us a letter which he said was from your hand. [ . . . ] You enumerate all those who are leagued with you against us, you name them and say the king of this land and the king of that land, this count and that count, and the archbishops, marquises and knights. But we wished to enumerate those who are in our service and who listen to our commands and obey our words and would fight for us, this is a list which could not be reduced to writing. [ . . . ] The Bedouin are with us, and they alone would be sufficient to oppose all our enemies. And the Turkmans alone could also destroy them. It might be a stretch to say that Saladin’s reply was angry, but it was full of banter: Hey, Frederick! This jerk Henry came with this angry letter and said it was from you, but I know the two of us are best friends. Since you probably didn’t really say all those mean things, feel free to ignore this huge list of armies that I have that could totally beat you up. After this, Frederick joined (and died during) the Third Crusade to retake Jerusalem from Saladin.

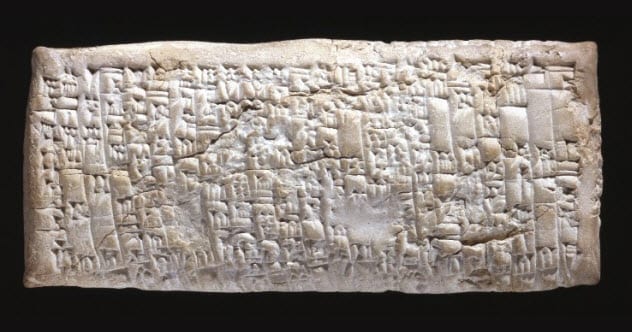

8 Complaint Tablet To Ea-Nasir

Nanni was in the market for copper almost 4,000 years ago in 1750 BC in the Babylonian city of Ur. But he found himself extremely unhappy with the copper ingot shipment he received from a merchant named Ea-nasir. In what is possibly the most relatable letter on this list, Nanni sent Ea-nasir a customer service complaint. What might be less familiar to us is that he wrote this complaint in cuneiform on a clay tablet[3] that is now housed in The British Museum: Tell Ea-nasir: Nanni sends the following message: When you came, you said to me as follows: “I will give Gimil-Sin (when he comes) fine quality copper ingots.” You left then but you did not do what you promised me. You put ingots which were not good before my messenger (Sit-Sin) and said: “If you want to take them, take them; if you do not want to take them, go away!” What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt? I have sent as messengers gentlemen like ourselves to collect the bag with my money (deposited with you) but you have treated me with contempt by sending them back to me empty-handed several times, and that through enemy territory. Is there anyone among the merchants who trade with Telmun who has treated me in this way? You alone treat my messenger with contempt! On account of that one (trifling) mina of silver which I owe you, you feel free to speak in such a way, while I have given to the palace on your behalf 1,080 pounds of copper, and umi-abum has likewise given 1,080 pounds of copper, apart from what we both have had written on a sealed tablet to be kept in the temple of Samas. How have you treated me for that copper? You have withheld my money bag from me in enemy territory; it is now up to you to restore (my money) to me in full. Take cognizance that (from now on) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of fine quality. I shall (from now on) select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt. It seems as though Ea-nasir’s shady business practices may have caught up to him. Excavations of his home suggest that he had to downsize, maybe to accommodate the smaller income from his struggling copper business.

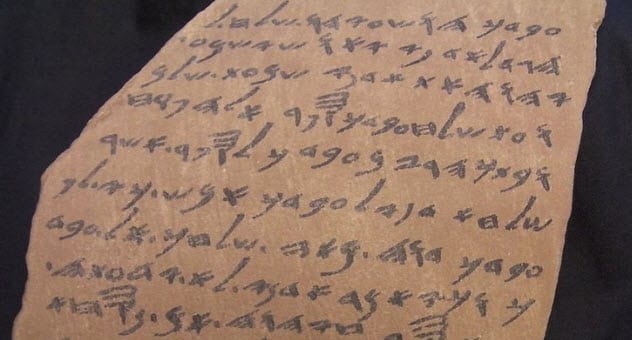

7 Sogdian Ancient Letter From Woman In Distress

The Sogdians were a people who were Iranian in origin. They played a key role in commerce on the Silk Road during the fourth through ninth centuries. One Sogdian woman, stranded in the city of Dunhuang, wrote a letter addressed to her husband: Behold, I am living . . . badly, not well, wretchedly, and I consider myself dead. Again and again, I send you a letter, but I do not receive a single letter from you, and I have become without hope toward you. My misfortune is this, that I have been in Dunhuang for three years thanks to you, and there was a way out a first, a second, even a fifth time, but he refused to bring me out. [ . . . ] Surely, the gods were angry with me on the day when I did your bidding! I would rather be a dog’s or a pig’s wife than yours![4]

6 Esarhaddon’s Refusing A Letter

During the Neo-Babylonian Empire, clay cylinders were employed as letters. The message was written directly on the surface of the cylinder, and then an outer sheath of clay formed an envelope around the letter with the sender’s and recipient’s names inscribed. Much like today’s letters, you could usually tell who was sending you a letter before opening it—if you opened it. One man named Esarhaddon received a letter from someone he viewed as not a real Babylonian even though that person lived in Babylon. Esarhaddon sent the letter back, with an angry letter of his own that detailed his reason: I am herewith sending back to you, with its seals intact, your completely pointless letter that you sent to me. Perhaps you will say: “Why did he return it to us?” When the citizens of Babylon, who are my servants and love me, wrote to me, I opened their letter and read it. Now, would it be good that I should accept and read a letter from the hands of criminals who disrespect the god?[5] Whether or not the person lived in Babylon, Esarhaddon didn’t view him as a citizen and so thought it was pointless to even read the letter sent.

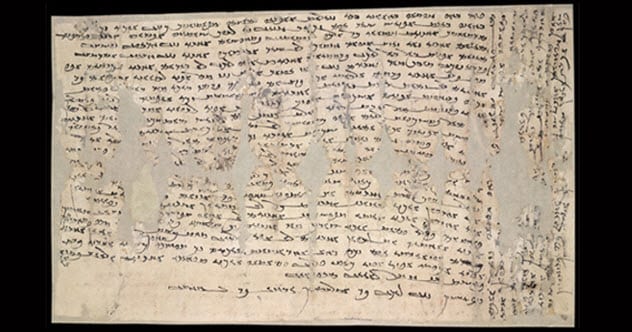

5 Hoshayahu’s Letter Defending His Literacy

In some cases, ancient messengers who delivered a letter would read it aloud for the recipient. In other cases, a scribe in the service of the recipient would. Sometimes, though, the recipient would be proud to read it himself, such as Hoshayahu, an ancient Hebrew civil servant in the city of Lachish. His superior insinuated that Hoshayahu couldn’t read his own letters! The nerve. No one reads Hoshayahu’s letters but him! He wrote to his superior to tell him as much: And now, please explain to your servant the meaning of the letter which you sent to your servant yesterday evening. For your servant has been sick at heart ever since you sent that letter to your servant. In it, my lord said: “Don’t you know how to read a letter?” As Yahweh lives, no one has ever tried to read me a letter! Moreover, whenever any letter comes to me and I have read it, I can repeat it down to the smallest detail.[6]

4 Thonis’s Letter To His Father

In the third century AD, Thonis was only trying to get his father, Arion, to sign up a teacher with whom Arion had already made arrangements. Arion had barely written Thonis and had been repeatedly delaying a visit to get this teacher locked in. Thonis begins his letter with the customary greetings, wishing his father good health and so on. Then Thonis immediately starts badgering his dad to get his butt there as soon as possible. Thonis ends cordially enough and then hastily tosses in a reminder to care for the pets he left at home. To my respected father, Arion, Thonis sends greetings. Most of all, I say a prayer every day, praying to the ancestral gods of this land in which I am staying that I find you and all our family flourishing. Now look, this is the fifth letter I have written, and except for one, you have not written to me, even about your being well, nor have you come to see me. Having promised me “I am coming,” you didn’t come so that you could find out whether the teacher was attending to me or not. So, practically every day, he asks about you, “Isn’t he coming yet?” and I say just the one word, “Yes.” [ . . . ] So make the effort to come to me quickly so that he can teach me—as he is keen to do. If you had come up here with me, I should have been taught long before. And when you do come, remember what I have written to you many times. Come quickly to me before he leaves for the upper territories. I send many greetings to all our family by name and to my friends. Goodbye, my respected father, and I pray that you may fare well for many years along with my brothers (safe from the evil eye). Remember my pigeons.[7]

3 Pliny The Younger’s Letter To Septitius Clarus

Pliny the Younger, a Roman senator and a powerful man, had been stood up. He had invited one of his dear friends, Septitius Clarus, to dinner, and Septitius never arrived. Pliny wrote this letter to his friend demanding to be reimbursed for the expense of the wasted dinner. Though at first glance it might seem angry, it only arrives on our list mockingly so. More than anything, Pliny just seemed bummed that he and his friend didn’t get to party: AH! You are a pretty fellow! You make an engagement to come to supper and then never appear. Justice shall be exacted; you shall reimburse me to the very last penny the expense I went to on your account; no small sum, let me tell you. Oh! you have behaved cruelly, grudging your friend, I had almost said yourself; and upon second thoughts, I do say so; in this way: for how agreeably should we have spent the evening, in laughing, trifling, and literary amusements! You may sup, I confess, at many places more splendidly; but nowhere with more unconstrained mirth, simplicity, and freedom: only make the experiment, and if you do not ever after excuse yourself to your other friends to come to me, always put me off to go to them. Farewell.[8]

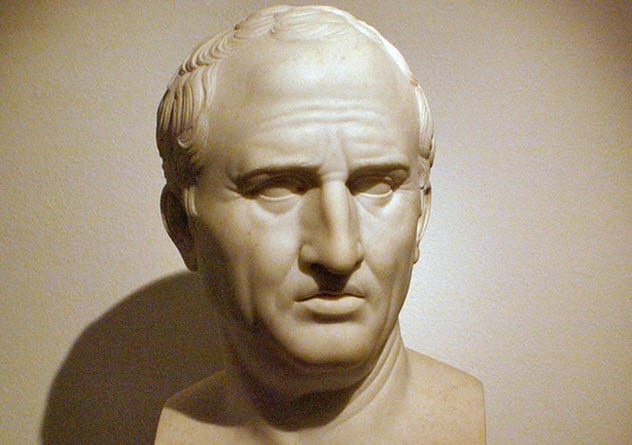

2 Cicero’s Letter To M. Fadius Gallus

Fadius Gallus was authorized by Cicero, a Roman statesman, to make purchases on his behalf. On one occasion, unknown to Cicero, Fadius Gallus purchased a collection of statues for Cicero’s use. When the statesman arrived home, he received a letter from the party to whom Cicero now owed money for the statues. But Cicero hated the figures. To his credit, he reassured Fadius Gallus that he would honor the arrangement. But, my dear Gallus, everything would have been easy if you had bought the things I wanted and only up to the price that I wished. However, the purchases which, according to your letter, you have made shall not only be ratified by me, but with gratitude besides. For I fully understand that you have displayed zeal and affection in purchasing (because you thought them worthy of me) things which pleased yourself—a man, as I have ever thought, of the most fastidious judgment in all matters of taste. Still . . . there is absolutely none of those purchases that I care to have.[9] Cicero then goes into vivid detail about why Fadius screwed up in purchasing these outrageously expensive statues: But you, being unacquainted with my habits, have bought four or five of your selection at a price at which I do not value any statues in the world. You compare your Bacchae with Metellus’s Muses. Where is the likeness? To begin with, I should never have considered the Muses worth all that money, and I think all the Muses would have approved my judgment. Still, it would have been appropriate to a library and in harmony with my pursuits. But Bacchae! What place is there in my house for them? What, again, have I, the promoter of peace, to do with a statue of Mars? I am glad there was not a statue of Saturn also. For I should have thought these two statues had brought me debt! I should have preferred some representation of Mercury. I might then, I suppose, have made a more favorable bargain with Arrianus. You say you meant the table stand for yourself; well, if you like it, keep it. But if you have changed your mind, I will, of course, have it. For the money you have laid out, indeed, I would rather have purchased a place of call at Tarracina to prevent my being always a burden on my host.

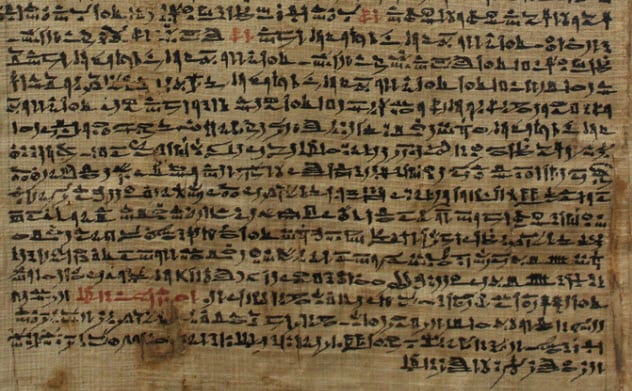

1 An Ancient Egyptian Widow’s Appeal To Her Dead Brother

In ancient Egypt between at least 2686–1069 BC, there was a custom of writing to deceased loved ones to beg them for help. The dead were considered very powerful and able to intervene for the living, maybe even pleading cases in a court of the underworld to stop whatever bad fortune was afflicting living relatives. One such letter was written from a grieving mother to her dead brother, begging him to help her daughter. This personal letter is one of the first recorded messages from a woman in Egypt: A sister speaks to her brother. The sole friend Nefersefkhi. A great cry of grief! To whom is a cry of grief useful? You are given it for the crimes committed against my daughter evilly, evilly, though I have done nothing against him, nor have I consumed his property. He has not given anything to my daughter. Voice offerings are made to the spirit in return for watching over the earthly survivor. Make you your reckoning with whoever is doing what is painful to me, because my voice is true against any dead man or any dead woman who is doing these things against my daughter.[10]