10 Shimabara Rebellion

Christianity had begun to flourish in Japan during the 17th century, as the country had been slowly opening up more and more to foreigners (mainly Europeans) since 1543. However, the influence of nanbans (Japanese for “southern barbarians,” a term loosely applied to Europeans) began to worry the ruling shogunate, and the age of sakoku (“closed country”) began to take shape. Christianity was seen as one of those influences. There were many Christian peasants, and their dissatisfaction was the reason for the rebellion which occurred in the Shimabara Peninsula in 1637. Like many before them, the local officials of the area were taxing the peasants heavily, utilizing their powers to abuse the civilians in any number of ways. The spark that lit the fire was the murder of the daimyo’s henchman, who was killed because he was torturing a local farmer’s daughter.[1] (A daimyo was similar to a feudal lord.) Fighting broke out, and the peasants quickly assembled into a massive group. They were aided by former samurai, many of whom had converted to Christianity, who became leaders of the rebellion. Unable to defeat the rebels with local forces, the shogun set 120,000 men to kill the civilians. Though they held out for a while, the rebels were eventually killed to the last person, women and children included. Estimates range from 20,000 to 37,000 deaths. As a result, Christianity, as well as other foreign influences, were increasingly forced out of Japan.

9 Bombing Of Dresden

Often seen, perhaps erroneously, as an act of revenge for the similar bombing of their own cities suffered at the hands of the Luftwaffe, Britain’s bombing of the German city of Dresden in February 1945 has been covered in controversy ever since. One of the reasons for this controversy is that the city was not of military or economic importance.[2] Rather, the bombing was an attack on a culturally important city: the “Florence of the Elbe.” The Nazis had been bombing British cities for a while by 1945, and in the eyes of some, the bombing of German cities was just their chickens coming home to roost. So, from February 13 to 15, 1945, British planes (with a few Americans) flew over the city of Dresden, devastating the area. Like many attacks during World War II, the death tolls are disputed, with ranges as low as 35,000 and as high as 135,000. However, what isn’t in dispute is the complete destruction of nearly every building in the city. Only a handful of the historic buildings in the city were ever rebuilt.

8 Guangzhou Massacre

Thanks to a number of natural disasters which resulted in widespread famine, Huang Chao led an agrarian rebellion throughout China, eventually culminating with his ascension to the throne. The Tang dynasty attempted, unsuccessfully, to defeat Huang’s forces, who managed to sack a number of provincial capitals. Huang then turned his sight toward Guangzhou, which had suffered at the hands of a rebellious army more than a century earlier. (Thousands of foreign-born merchants were killed.) So, from 878 to 879, Huang’s men attacked the city, specifically targeting Muslims, Jews, and Christians, initiating a xenophobic pogrom, an act with which humanity is all too familiar. An otherwise nondescript Arab traveler named Abu Zaid Hassan wrote about the attack, claiming that as many as 120,000 people were massacred.[3] As for Huang, his army was eventually defeated, and he died at the hands of his nephew. His entire reign lasted only four years.

7 Manila Massacre

Colloquially known as the “Pearl of the Orient,” Manila was a magnificent city, the capital of the Philippines, and it would suffer more than any Allied city outside of Warsaw. First occupied by Japan in 1942, the Pacific island chain endured years of military abuse, with hundreds of thousands of Filipinos perishing during the intervening years. Finally, in 1945, US forces arrived, with General MacArthur fulfilling the promise he gave three years prior to return to drive the Japanese away and retake the country. However, the Japanese military refused to give up easily, and in a continuance of their policy at the time, they began to speed up their killing of civilians. During the Battle of Manila, which lasted about a month, around 70,000 Filipinos were raped and/or massacred by the Japanese army.[4] A further 30,000 died in the crossfire between Japan and the US. In addition to the civilian casualties, vast portions of the city were destroyed in the fighting, some down to the very last building.

6 Firebombing Of Tokyo

While deserving of much of their attention, the nuclear weapons dropped on Japan at the end of World War II weren’t the only causes of devastating numbers of civilian deaths suffered there: Another example is the firebombing of Tokyo in 1945. Later known by the name “the Night of the Black Snow,” Operation Meetinghouse took place from March 9 to March 10, with US bombers dropping 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs on the city. In all, 41 square kilometers (16 mi2) were burned, with as many as 130,000 deaths due to the resulting inferno.[5] The smell of burning human flesh was so severe that the pilots in the air had to don oxygen masks to keep from vomiting. When asked about it later, Curtis LeMay, the major general in charge, said, “Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at that time. It was getting the war over that bothered me.” The firebombing of Tokyo is often cited as one of the most, if not the most, destructive acts of war in the history of mankind.

5 Siege Of Changchun

May 23, 1948. The People’s Liberation Army began surrounding the city of Changchun, one of the largest in Northeastern China, defended by Nationalist forces. Not wishing to attempt to force their way into the city, the Communists decided to starve the population out, hoping to push the defenders to surrender bloodlessly. The civilian population of around 500,000 was caught unprepared, and they quickly ran out of food. It later became clear there was an ulterior motive to the siege: The Communists were purposely starving the citizens, whom they saw as the enemy. Stories of women sold to awaiting husbands-to-be for mere scraps of food were all too common. When the siege finally ended in October, a minimum of 160,000 civilians had starved to death. Those who had survived had only managed to live by eating virtually every edible thing in the city, down to the bark on the trees and the grass in the fields. A Communist soldier later remarked, “We’re supposed to fighting for the poor, but of all these dead here, how many are rich? [ . . . ] Aren’t they all poor people?”[6]

4 Siege Of Jerusalem

Though Jerusalem has seen a number of sieges take place outside its walls, perhaps none was bloodier than the climactic battle of the First Crusade. Initiated in 1095 by Pope Urban II’s decrying of the persecution suffered by Christians in the Holy Land, tens of thousands of Western Europeans streamed into the Middle East like a deluge, massacring anyone who was in their way, soldier or civilian.[7] Facing little resistance, the wave of crusaders finally broke against the walls of Jerusalem on June 7, 1099. Finding it to be incredibly well-protected, the Christian forces began constructing three massive siege engines with which to defeat the defenses. After about a month, the crusaders finally broke into the city, and the slaughter began. A contemporary account of the fighting told a horrifying tale of senseless barbarism, of deaths so numerous that, “The blood was running up to ankles of the mounted Frankish knights.” Whether or not that was hyperbole, tens of thousands of the civilian inhabitants were murdered, even women and children.

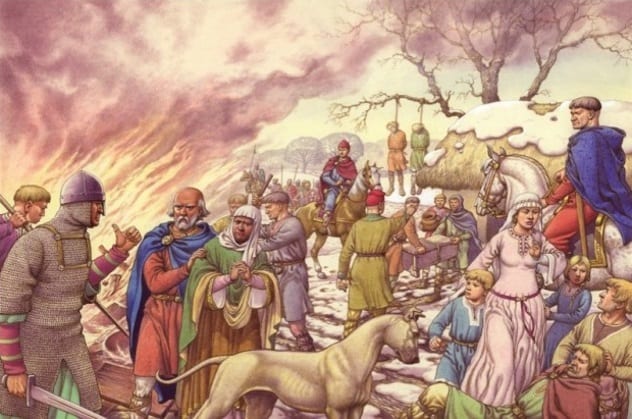

3 The Harrying Of The North

“Harry” is defined as “to ravage, as in war; devastate.” The Harrying of the North, undertaken by William the Conqueror against Northern England, lived up to that definition in every conceivable way. The old Viking lineage which persisted in the North refused to bow to William, with numerous rebellions popping up until the Norman ruler could only come to one conclusion: He would destroy the entire place, starving out the enemy.[8] That the civilians would also suffer was of no consequence. So, in the winter of 1069, William’s men marched north, destroying everything in their way, down to the last blade of grass. Though the Harrying directly killed a large number of civilians, many more perished as a result of the enormous famine which resulted from the destruction of the land, livestock, and food stores. The campaign was so horrific that Orderic Vitalis, a monk who otherwise wrote glowingly of William, said the following: “I can say nothing good about this brutal slaughter. God will punish him.” Though the death tolls are often debated, contemporary reports say as many as 100,000 people died.

2 Massacre Of Novgorod

In late 1569, the grand prince of Moscow had begun to reach the peak of his paranoia, believing that the people of Novgorod were about to turn over their city to Poland. Better known as Ivan IV, or Ivan the Terrible, he decided that the citizens of Novgorod would need to be punished. So, along with his 1,500-man personal guard, the tsar marched on the city, ravaging smaller towns and villages along the way, warming up for what was to be the horrifying main event. Arriving just after the start of the new year, Ivan IV began the horror with the priests and monks of Novgorod, having them beaten to death with staffs.[9] He then moved on to the populace, setting up a special court in the city in which to extract “confessions” through torture. Often, the victims were then thrown into the Volkhov River to drown or freeze to death. Man, woman, and child alike met the same fate, and their blood ran so much that the snow around the city was painted red. When it was all over about five weeks later, at least 60,000 citizens were dead, and it took six weeks to clear their bodies.

1 Rotterdam Blitz

Expecting to remain neutral as they had during World War I, the people of Rotterdam in the Netherlands never expected the Nazis to come knocking. But knock they did. On May 10, 1940, the Germans attacked. They were ultimately repelled and locked into a stalemate with their Dutch adversaries. Unwilling to risk too many lives or time, Nazi general Rudolf Schmidt issued an ultimatum: Surrender or face the might of the Luftwaffe. The Dutch refused. A few days later, May 14 to be exact, the bombing began.[10] Between 80 and 90 German planes indiscriminately dropped their ordinance all over the city. Owing to the fact that they had virtually no antiaircraft weapons in the city, not to mention inferior air power, all the Dutch could do was watch as their city was leveled. In the end, nearly 1,000 people died, and most of the historic buildings within the city center were destroyed. Though the deaths directly attributed to the Rotterdam Blitz are low, the argument could be made that it, along with the other Nazi bombing raids, unleashed the extensive destruction perpetrated by the Allies. As the British air marshal Arthur Travers Harris said, “The Nazis entered this war under the rather childish delusion that they were going to bomb everyone else, and nobody was going to bomb them. They sowed the wind, and now they are going to reap the whirlwind.”