Something you may not have thought about is the fact that a number of people have died inside the White House (although perhaps you’ve heard the claims that it’s haunted). The following ten entries delve into the little-known facts of those whose lives ended inside the presidential mansion as well as the aftermath and the loved ones they left behind.

10 Rebecca Van Buren

Eighteen years before Martin Van Buren became the eighth president of the United States, he lost his 35-year-old wife, Hannah, in 1819 to tuberculosis. Never to remarry, Van Buren’s daughter-in-law, Angelica, began performing the duties of first lady following her marriage to his son, Abraham. Almost immediately, the wealthy Southern belle was adored by Washington’s elite, who admired her charm, her graciousness, and her marriage, which became a romantic inspiration to America’s youth. Much to the president’s delight, by 1839, Angelica and Abraham were living in the White House. Unlike Van Buren’s youngest son John, a notorious playboy whose extravagant and luxurious lifestyle consistently provoked the press, Abraham and his wife were the epitome of Van Buren’s envisioned picturesque first family. The jubilation within the mansion came full circle with the birth of Abraham’s first child, Rebecca, in March 1840. Sadly, Rebecca fell ill immediately after birth and never recovered, passing away six months later and becoming the first to die inside the White House. Overcome with grief, President Van Buren immersed himself in his work. He became noticeably more stringent, and those around him claimed that the death of his granddaughter had morphed a once blissful and optimistic president into a tyrant.[1]

9 Madge Wallace

Madge Wallace was your stereotypical mother-in-law, and her demeaning and bitter ways undoubtedly contributed to President Harry S. Truman’s personal discontent. Despite becoming the 33rd president of the United States, Truman was seen as nothing more than a simple dirt farmer and failed haberdasher in the eyes of Wallace, who considered him unworthy to be wed to her daughter, Bess. Her unwavering sullenness perhaps originated in 1903, when her husband, David Wallace, shot himself in the head, leaving the family deeply scarred with an abiding sense of shame. Nonetheless, Mrs. Wallace’s belittling of her son-in-law was unfounded, even more so after he successfully guided a nation through a time of world peril. According to historian Alan L. Berger, Wallace, “a confirmed anti-Semite,” consistently badgered Truman about his positive stance on Israel in addition to questioning his qualifications as president. Addressing him only as “Mr. Truman,” Wallace wasn’t shy about supporting Truman’s opponents, such as Governor Thomas Dewey of New York.[2] In light of the vile treatment at the hands of his wife’s mother, Truman ironically spoke well of Mrs. Wallace upon her passing in her White House bedroom on December 5, 1952, stating, “She was a grand lady. When I hear these mother-in-law jokes I don’t laugh.”

8 Letitia Tyler

Letitia Tyler was a socially engaged member of Washington’s elite society. Sadly, in 1839, the mother of seven would suffer a stroke, leaving her partially paralyzed. As luck would have it, her husband, John, would soon be chosen as the vice presidential candidate for William Henry Harrison. Nonetheless, his days of attending to Letitia’s needs at their home in Williamsburg would soon come to an end in April 1841, when he succeeded to the presidency upon the sudden death of President Harrison. Given her physical limitations, Mrs. Tyler was not present at her husband’s swearing-in. Nevertheless, she went on to manage all of the family and public social affairs from the confines of her bedroom. Spending the majority of her days in her room beside her Bible and prayer books, she directed many charitable contributions from her own personal wealth to the poor of Washington. After political turmoil plagued the Tyler administration, First Lady Letitia suffered a second stroke. For days, she wrote her children, pleading for their return to Washington, DC. It is said that on the night of her death, Letitia, holding a rose in her hand, turned toward the door, searching for her son who would never arrive. On the evening of September 10, 1842, Letitia Tyler became the first of three first ladies to die during their incumbency. As the city bells tolled in her honor, her casket lay in state in the East Room while crowds gathered outside “sobbing, wringing their hands, and every now and then crying out, ‘Oh, the poor have lost a friend.’ “[3]

7 Ellen Wilson

During the first three months of her husband’s administration, First Lady Ellen Wilson hosted over 40 White House receptions, musicals, and recitals. Her love for the arts proved comedic to the press, who often criticized her fashion sense—or lack thereof. Ironically, it would be her artistic eye that left an enduring contribution to the presidential mansion, including the creation of the Rose Garden. Ellen suffered in private, sparing her loved ones the knowledge that she was dying from a kidney ailment known as Bright’s disease. On July 23, 1914, Dr. Cary Grayson moved into the White House, only to pack up 13 days later following the death of Mrs. Wilson. President Wilson was given the unexpected news of his wife’s grave condition merely 48 hours before her passing. He later stated that on her deathbed, Ellen uttered that she could “go away more cheerfully” if she knew that the alley clearance bill would pass. Word of this was sent to Capitol Hill, and her request was immediately granted. On August 6, 1914, Ellen became the third presidential wife to die in the White House. Her remains were rested on her bed in the mansion before a private funeral four days later in the East Room. Her grave would go unmarked (albeit with a headstone) for a full year, drawing attention to the fact that the widower president had already publicly moved on with Edith Bolling Galt, whom he’d marry in December 1915.[4]

6 Charles G. Ross

Charles G. Ross, press secretary under President Harry Truman, was often publicly flagged by the members of the press corps, who claimed that he lacked much-needed administrative experience. It became increasingly evident that Ross was not always aware of everything that was going on in the presidency, nor did the man, who was a poor public speaker, coordinate news releases with government departments and agencies in a timely fashion. Nevertheless, Ross’s position in the White House was secure, given his close friendship with the president. The two men had known one another since their childhood in Independence, Missouri, where they both graduated, along with Truman’s wife Bess, from Independence High School in 1901. When Ross was called upon by Truman to be his press secretary in 1945, it would be a position he would hold until his unexpected death five years later.[5] After giving a press conference on the morning of December 5, 1950, Ross returned to his office in the White House to prepare for his upcoming televised news statements scheduled for that afternoon. Moments later, White House staff received a summons that Ross had collapsed at his desk, dying of a heart attack. President Truman said of his friend, “We all knew that he was working far beyond his strength. But he would have it so. He fell at his post, a casualty of his fidelity to duty and his determination that our people should know the truth, and all the truth, in these critical times.”

5 Frederick Dent

Before becoming the 18th president of the United States on March 4, 1869, Ulysses S. Grant and his wife Julia faced grave financial hardships for well over a decade. Struggling to produce an income from the 60-acre farmland he inherited from Julia’s father, Frederick Dent, the bleak future Grant foresaw for him and his family was becoming an incessant and debilitating mental strain. Grant’s hardships were only made worse by the unremitting belittling of his father-in-law, who openly chastised him as a failure, sending him falling into deeper despondency. Frederick Dent’s relentless disparaging of his son-in-law continued even into Grant’s presidency. On the cold winter evening of December 15, 1873, Grant found a respite from the struggles of office and his insufferable in-law by dining out with his wife and son, Fred. The three returned to the White House close to midnight only to discover that a physician had been summoned to Dent’s bedside. Dent was found to be in a “quiet slumber.” At 11:45 PM, Dent passed away, relieving Grant of the heavy burden he had fruitlessly carried for all those years trying to please an impossibly difficult man. Following his funeral in the Blue Room of the mansion, Dent’s remains were shipped back to St. Louis for burial. Grant, along with his son, accompanied the casket, while his distraught wife remained in Washington, DC.[6]

4 Caroline Harrison

Caroline Harrison, wife of the 23rd president of the United States, Benjamin Harrison, was instrumental in extensively remodeling the White House, including the installation of electricity. In addition, the first lady used her exceptional painting skills to design new formal presidential china, which, to date, remains one of the main public attractions of the mansion. Her social obligations and enthusiastic involvement in the expansion and renovation of the White House would come to a sudden halt in the winter of 1891, after she suffered numerous bouts of debilitating bronchial infections. When her condition deteriorated in the summer of 1892, Caroline was officially diagnosed with tuberculosis, with little hope of recovery. Despite frequent attempts at a cure, including various operations to drain fluids from the pleural cavities of her lungs, Caroline died after a painful struggle at 1:40 AM on October 25, 1892, with President Harrison by her side. Her private funeral in the East Room of the mansion two days later required an invitation to attend. Her Spanish red cedar casket, adorned with wreaths from dignitaries around the world, was then accompanied by her family to Indianapolis for burial.[7] Just one month after her death, Caroline’s father, Reverend John Witherspoon Scott, passed away in the White House at the age of 92.

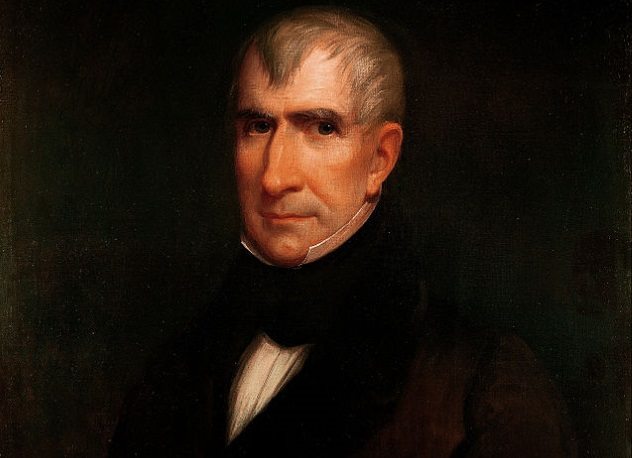

3 William Henry Harrison

On March 4, 1841, William Henry Harrison was sworn in as America’s first Whig president. The day was bitterly cold, and a stubborn 68-year-old Harrison declined to wear a jacket, hat, or gloves in what would become the longest Inaugural Address in US history. Just 31 days later, the ninth president of the United States would take his last breath inside the White House.[8] In the weeks leading to his death, a bedridden Harrison was thought to be suffering from pneumonia, as originally diagnosed by his physician, Dr. Thomas Miller. In recent years, however, the untimely death of America’s shortest-serving president is best explained by enteric fever contracted by pathogens in the White House water supply. A mere seven blocks from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue was the city’s depository for “night soil,” a field of stagnated human excrement that became a breeding ground for deadly bacteria, including Salmonella typhi and S. paratyphi. This would explain Harrison’s sinking pulse and cold, blue extremities prior to his death, classic manifestations of septic shock. The standard treatment that Dr. Miller administered only exacerbated the president’s condition. The opium Harrison was given facilitated pathogenic bacteria into the bloodstream by retarding the intestines’ motility, and repeated enemas potentially resulted in ulcer perforation, causing sepsis.

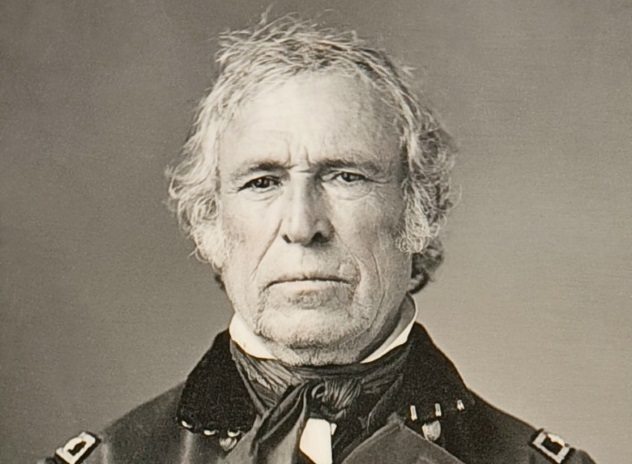

2 Zachary Taylor

For four long, agonizing days, President Zachary Taylor was bedridden inside the White House, suffering from severe cramps, diarrhea, nausea, and dehydration. Taylor ultimately succumbed to his acute illness on July 9, 1850, just 16 months into his term. The exact cause of death has always been disputed by historians, many of whom have claimed that the 12th president contracted cholera, while others hinted at possible foul play due to arsenic poisoning. This theory led to the exhumation of Taylor’s remains at the National Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky, on June 17, 1991. Given that 141 years had passed since his death, a team of medical examiners found no organs or skin on Taylor and, thus, had to rely on bone, eyebrows, and pubic hair in order to test for traces of arsenic. They found only small amounts of the chemical consistent with any human being on planet Earth. In addition, no traces of mercury, lead, or other toxic metals were found, indicating that the president was not poisoned. In fact, the only thing that stood out to the medical examiners was Taylor’s “unusually good set of teeth,” especially for a 65-year-old man living in pre-fluoride days. As for the cause of his unexpected and sudden demise, historians continue to cite gastroenteritis as the fatal culprit.[9]

1 Willie Lincoln

On the cold winter day of February 20, 1862, 11-year-old Willie Lincoln took his last breath, casting a pall over the White House that would linger for the remainder of his father’s presidency. The child, who is believed to have contracted typhoid fever from the mansion’s contaminated water supply, was clothed in usual everyday attire and placed in a plain metallic coffin in the East Room of the White House. The weeks prior to his death were an agonizing stretch for the president and first lady, who, on the inside, died along with their son, plunging the couple into insurmountable sorrow. According to Elizabeth Keckley, a former slave who had become Mrs. Lincoln’s seamstress and confidante, President Lincoln’s grief “unnerved him, and made him a weak, passive child. I did not dream that his rugged nature could be so moved.” Mrs. Lincoln was inconsolable to the point that the president led her to a window and pointed toward St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, an insane asylum, stating, “Mother, do you see that large white building on the hill yonder? Try and control your grief, or it will drive you mad, and we may have to send you there.” Following a long procession through unpaved streets, Willie’s remains were placed in a marble vault in Oak Hill Cemetery as a temporary resting place until the Lincoln family returned to Illinois. Even as he tried to hold the country together, the president consistently visited his son’s tomb until his assassination on April 15, 1865. In the end, the caskets of father and son were placed beside one another aboard the presidential funeral train for their journey home.[10] Adam is just a hubcap trying to hold on in the fast lane.