But what’s in the subtext of history? Ever wonder about the interesting little tidbits that slip through the cracks? Here are 10 things your history teacher forgot to mention.

10 Saddam Hussein’s Key To Detroit

“He was [a] very kind person, very generous, very cooperative with the West,” said Reverend Jacob Yasso of Chaldean Sacred Heart in Detroit. The Chaldean religion is a sect of Catholicism prevalent in Iraq, a population that is dominated by Muslims. It is practiced by tens of thousands of Americans of Middle Eastern descent. The person in question? Saddam Hussein. In 1979, Yasso congratulated Hussein on his presidency and Hussein generously donated $250,000 to Yasso’s church. The following year, Yasso visited Iraq as a guest of their government. With permission of the mayor of Detroit, he presented Hussein with the key to the city.[1] Hussein’s response? “I heard there was a debt on your church,” he said. “How much is it?” Hussein gave the church another $200,000. Yasso later changed his mind about Hussein. “The job the United States trusted to him is done,” Yasso said. “Now he’s no good.”

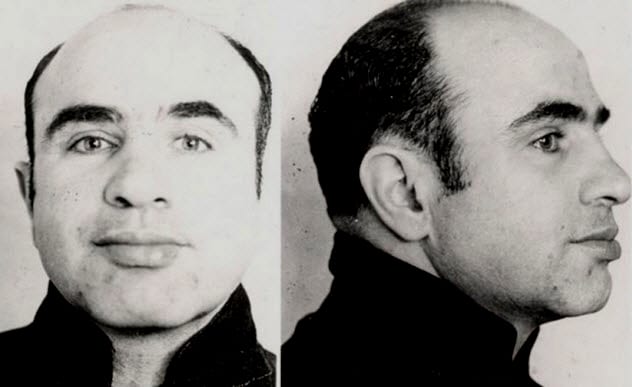

9 Al Capone’s One Mistake

Al Capone was the king of crime in Chicago during the Roaring Twenties. He ruled a criminal empire during Prohibition by controlling gambling, bootlegging, prostitution, and most other crime in Chicago. The FBI knew of his criminal activities. But they couldn’t take any action against Capone because none of his crimes were federal offenses. They had to sit by and watch local law enforcement fail to take him down, a wait that became even more infuriating after the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre. Finally, in 1929, Capone slipped up. When he was subpoenaed to appear before a federal grand jury as a witness in February, Capone claimed that he was sick at home and unable to make it. However, FBI agents quickly found him in Miami, out and about and as healthy as ever. Capone was cited for contempt of court and sent to jail. However, they were unable to hold him and he was released on bond. But that was the beginning of the end. When Capone was finally tried for the contempt of court citation, a federal judge sentenced him to six months in prison. This gave federal Treasury agents enough time to gather evidence that Capone had failed to pay his income taxes. In the end, the murdering, devious crime boss had forgotten to keep an eye on his real enemy: the IRS.[2]

8 The Longest War In History

The longest war in history was an accident. In 1651, the Dutch were fighting with the Royalists and had driven them back to the Isles of Scilly. Eager to make up for the cost of the war, the Dutch sent warships to the islands to demand reparations. It didn’t work. So Admiral Maarten Tromp officially declared war on the Isles of Scilly. Whether Tromp had the authority to do so remains unclear. But after forcing the Royalists to surrender three months later, the Dutch sailed back to the Netherlands. However, they forgot an important bit of last-minute business: declaring peace with the Isles of Scilly. The matter was all but forgotten until 1985. At that time, Roy Duncan, a local Scilly historian, contacted the Dutch embassy asking if there was any truth to the preposterous rumors he had uncovered of an ongoing war between the two nations. The embassy turned up documents that seemed to indicate that the two nations had been at war for 335 years. Duncan quickly asked the Dutch ambassador, Rein Huydecoper, to sign a peace treaty.[3] On April 17, 1986, Huydecoper signed the agreement to end the bloodless, nearly forgotten, longest war in history.

7 The Shortest War In History

A mysterious death. A shady relative. A colonial British presence. The perfect ingredients for war. In 1896, Hamad bin Thuwaini was ruling over Zanzibar, a protectorate of the British Empire, after being instated as a “puppet” sultan by the British. His reign had lasted just three years when he suddenly died in his palace on August 25. Rumor has it that his cousin Khalid bin Barghash had him poisoned, a belief seemingly confirmed by the fact that Barghash quickly moved into the palace and assumed the status of sultan without British permission. Basil Cave, the chief British diplomat in the area, caught wind of the affair and didn’t approve of the change in leadership. Cave requested the assistance of British military warships stationed nearby. While he awaited permission from Britain to open fire, Barghash gathered his own surprisingly well-armed forces. At 9:00 AM on August 27, Cave gave the order to begin bombarding the palace. At 9:02 AM, Khalid’s army was essentially destroyed and the palace began to crumble. By 9:40 AM, the sultan had pulled down his flag and the British ended their attack. In 38 minutes, the shortest war in history was over.[4]

6 The Pope’s Erotic Novel

Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini was one of the most read authors of the early Renaissance. He was an educated and eloquent man, and his book was filled with historical and literary allusions. It opens with a quote from Virgil’s Aeneid. It is also one of the earliest examples of an epistolary novel, a book that tells a story through letters. This book, The Tale of Two Lovers, follows the love story of Euryalus, an assistant to the duke of Austria, and Lucretia, a married woman. It is absolutely rife with erotic descriptions and imagery, most likely contributing to its widespread popularity. Later, Piccolomini became widely known again, though this time as Pope Pius II. He condemned slavery, supported the crusades, and started one of the first city planning projects in Europe. However, he retained his literary bent, with his autobiography, Commentaries, serving as his most important and acclaimed work. The Tale of Two Lovers was widely read after his election to the papacy[5] and remains so to this day, both for its own merit and the illicit pleasure taken in an erotic novel written by a pope.

5 The Hatchet-Wielding Prohibitionist

Carrie A. Moore was born in Kentucky in 1846. Her first husband was an alcoholic who could not support her or their child. He died six months after the child was born. Later, after marrying preacher David Nation, Carrie became deeply religious. She also became incredibly involved in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and working with prisoners. During her work in jail, she began to believe that alcohol was the root of the prisoners’ problems. So she started her crusade against the illegal bars active in Kansas. She and another member of the WCTU attempted to close down bars by standing outside and loudly singing hymns and praying. After supposedly receiving a message from God, Carrie turned to violence.[6] She threw bricks at bars, and someone handed her a hatchet, which she used to continue her destruction of bars and their liquor supplies. Carrie Nation—a strong woman who was 183 centimeters (6’0″) tall—quickly drew national attention. The WCTU awarded her a medallion with the inscription: “To the Bravest Woman in Kansas.” In 1903, Carrie A. Nation officially became Carry A. Nation, claiming that she wanted to “Carry A Nation for Prohibition.” Though she did not live to see it, her hatchet-wielding legacy paved the way for the Eighteenth Amendment, which banned the manufacture and sale of alcohol, and the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote.

4 The Oneida Society

Chances are, your silverware comes from the Oneida Community. In 1848, John Humphrey Noyes left Vermont after being accused of adultery. He established his own community based on the religious belief of Perfectionism, which he adopted while studying at Yale Divinity School. He carefully selected 300 members, all of whom lived in a system of complete communism. The religion’s central tenet was complex marriage,[7] where every man was married to every woman and vice versa and all children were raised communally. Monogamy was heavily frowned upon, and younger members of the society were introduced to the “holy pleasures of the flesh” by an assigned older member of the community. Ultimately, those outside the community—called “The World” by the Oneida Community—accused the members of immorality. In 1881, the commune dissolved. What remains of the community is Oneida Ltd., the largest manufacturer of stainless steel cutlery in the nation. The transition from religious commune to successful corporation remains poorly documented, but there is no question as to the origins of Oneida Ltd. It is the only flatware maker with a factory in the United States, leaving an untarnished legacy in the wake of its utopian experiment.

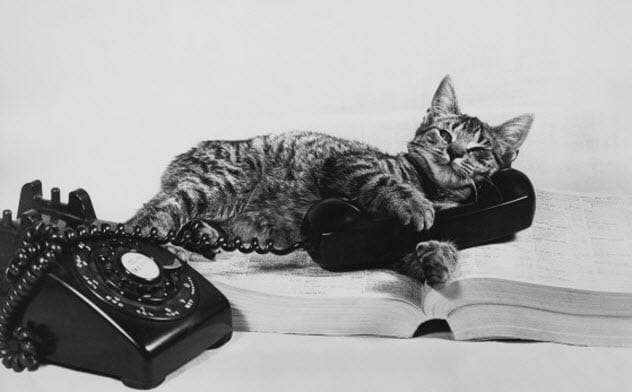

3 The Cat Telephone

Move over, Schrodinger. In 1929, Ernest Wever and Charles Bray, researchers at Princeton University, turned a live cat into a working telephone. They removed part of the cat’s skull to add an electrode to the right auditory nerve and to another part of the cat’s body. Then the researchers used a cable to attach the electrodes to a vacuum tube amplifier, and the amplified signals were sent to a telephone receiver in a separate, soundproof room. “Speech was transmitted with great fidelity,” the researchers said. “Simple commands, counting, and the like were easily received. Indeed, under good conditions, the system was employed as a means of communication between operating and soundproof rooms.”[8] The success, however, could have been a fluke. To ensure that it wasn’t, Wever and Bray killed the cat. The sound faded and died, proving that the functionality of the telephone came from the life of the cat.

2 The Dancing Plague Of Strasbourg

In July 1518 in Strasbourg, France, Frau Troffea began to dance. People laughed and clapped at the lone woman dancing in the streets to no discernible music. But they slowly stopped laughing when she did not stop dancing. She danced day and night for six days. Her dancing fever proved contagious. Within a week, 34 people had joined her. By the end of a month, there were 400. At the height of the dancing fever, 15 people died each day from heart attacks, strokes, and exhaustion. The town’s government decided to lean into the storm, constructing a makeshift dance floor and hiring musicians for the dancers in hopes that they would attain their fill of dancing and stop. However, these measures did nothing but encourage others to hop on the dance floor and join the craze. After a month, the boogying suddenly stopped[9] and the dancers went home. Experts still disagree about what caused the craze. Many think that it was a social phenomenon caused by the stress of the times and not a mass medical disorder as some have speculated.

1 The Great Emu War

Would you fight an emu? In 1932, Australia tried. Finding it difficult to grow and sell their crops, farmers in Western Australia were struggling to stay afloat during the Great Depression. It didn’t help that their attempts to grow wheat had coincided with the emus’ breeding season and the birds were migrating inland. Finding the cultivated land of the wheat fields appetizing, the emus ate the crops, spoiled the wheat they didn’t eat, and left gaping holes in the fences. Dismayed, the farmers appealed to the government. Minister of Defense Sir George Pearce heard about the plight of the farmers and readily agreed to aid them in their war on the emus. Major G.P.W. Meredith of the Seventh Heavy Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery led the charge, arming soldiers with machine guns and chasing after any word of emu sightings, ready to face the enemy. The emus, however, proved to have a military strategy that far outstripped that of the Australian army. The flightless birds employed the guerrilla tactic of scattering in small groups, rendering the Australians’ weaponry ineffective. The Australians conceded defeat,[10] put down their machine guns, and headed home. In 1934, 1943, and 1948, when the farmers again requested military assistance to fight off the dastardly birds, the government refused.