In the United States alone, roughly 3,500 people die every year in fires. Every human being alive has likely had personal experience with the phenomenon, both good and bad. But even as intimately familiar with fire as all of us are, it can still surprise us with its many wonders. These 10 facts about fire, both scientific and cultural, will fuel the fire of your mind.

10 Fire Without Gravity Is A Sphere

On Earth with its constant gravity, a candle flame forms into the shape of a teardrop. It happens because the buoyancy of air changes depending on the temperature. The lighter, hotter air rises and pulls the colder air behind it. This causes the flame to form its signature shape. On Earth, the same process causes heavier material to sink to the bottom of a lake and form sediment. Oil will rise to the top of water for the same reason. However, in the microgravity on the International Space Station, oil doesn’t separate from water and sediment in water will disperse evenly and not sink. Likewise, the air heated because of a candle flame doesn’t rise but stays stationary. Instead of forming a teardrop shape, a candle in space forms a sphere of fire. Unlike fires on Earth, there are no visible flames. (They may be there, but they are very small.) Instead, the fire takes on the shape of a constant sphere, blue and bright. Unlike fire on Earth, these space fires let the oxygen come to them instead of reaching out in flickering directions to find it. The unique properties of microgravity also allow fires to burn at much cooler temperatures for much longer than on Earth.[1] A normal candle fire will be between 1500 and 2000 kelvins, but in microgravity, a candle can continue burning at 500 to 800 kelvins. These “cool” fires don’t produce soot, CO2, or water. If the effect could be replicated on Earth, it could mean more fuel-efficient engine starts for automobiles.

9 Forest Fires Create Their Own Weather

Uncontrolled forest fires can stretch for millions of acres. The largest recorded was in Russia, and it consumed 47 million acres of land. When fires reach these colossal sizes, they start to affect the atmosphere around them. The massive amount of heat moves air upward in tremendous quantities. “The fire gives air a push up above it, and then once it is moving up, the atmospheric instability accelerates it upwards, just like a building thunderstorm,” said meteorologist Evan Duffey.[2] As this hot air rises, it cools. Water droplets condense inside it, creating clouds and maybe even thunderstorms. A cloud created by a forest fire is called a pyrocumulus, and a “fire storm cloud” formed in this way is called a pyrocumulonimbus. Storms created by fires can benefit firefighting efforts by providing rain, but they can also hinder those same attempts by whipping up powerful winds that fan the fires even further. Sometimes, these strong winds can even be the basis for tornadoes, such as the one produced by the Carr Fire in California in 2018.

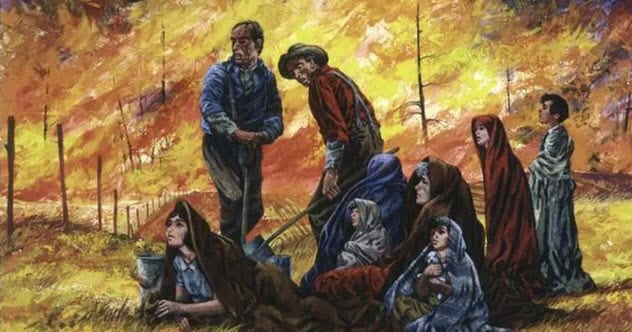

8 The Most Deadly Forest Fire Is Relatively Unknown

October 1871 was a very bad year for fires in the United States. In Chicago, between the 8th and 10th of October, a fire swept through the city, causing $200 million in damages and killing 300 people. It began a period of looting and lawlessness so bad that martial law was declared over the area and remained in effect for several weeks. The Great Chicago Fire attracted huge amounts of media attention and spurred significant economic growth in Chicago during the rebuilding. After the blaze, fire safety was even a platform that politicians ran on. But as deadly as it was, the Great Chicago Fire was small compared to its big brother. On the very same day, October 8, a fire started in the drought-stricken farmland of Wisconsin that reached an estimated size of nearly 1.2 million acres. It was known as the Peshtigo Fire, named after a nearby town that was devastated by the flames. The Peshtigo Fire killed an estimated 1,200–1,500 people, at least four times the number killed that day in the Great Chicago Fire. “What most researchers find so fascinating,” said Debra Anderson, an archivist for the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay Area Research Center, “is the effect it (the Peshtigo Fire) had on people’s lives. It was so horrific. Some people thought it was the end of the world.”[3] While the Chicago Fire received the majority of media attention and is more readily remembered, it was the Peshtigo Fire that wiped entire towns off the map forever.

7 Fire Is Art

Painter Steven Spazuk awoke from a dream with an idea to use fire as a tool for art. His first attempt at putting this idea into practice ended up turning his canvas into a crispy husk, but he didn’t give up. He continued perfecting the technique by using a more fire-resistant canvas. He experimented with many unusual kinds of brushes and eventually found the perfect varnish and sealer for his delicate creations. Finally, his dream was a reality: fumage or fire art. Spazuk begins his art by using a flame to apply soot to a white cardboard canvas. He says, “The flame always reacts to the air displacement, so I can’t control it. However, I can guide my lighter and the flame to create more or less the shape I want to create. Sometimes, I just let the flame do the work and create these magical forms.”[4] The resulting soot is then sculpted into an image. The final form is based on the patterns devised by the flame, and Spazuk uses a variety of unorthodox paintbrushes. Feathers and frayed ropes are in his toolbox, and he even created a brush from the hair his wife lost when going through chemotherapy. He used that brush to paint her portrait. Spazuk said about his chosen medium: Fire is a great metaphor for humans. Like fire, we are capable of great power, warmth and energy but also capable of destruction. [ . . . ] Drawing with fire captures infinite moments and gives me joy. The flame itself is a symbol of history—an untamable and unpredictable medium which has fascinated humans for centuries. The process is mesmerizing! Every flicker of a flame or brush of hair holds a different story.

6 Fire Is The Focus Of Zoroastrian Worship

There are about 100,000–200,000 practitioners of Zoroastrianism spread across the globe, including Iran and India. To them, fire represents the spiritual qualities within a person: order, beneficence, honesty, fairness, and justice. Collectively, these are called asha. During prayer, believers worship facing a light source. This could be the Sun, a wood fire, an oil lantern, or even one of the eternal fires kept in their places of worship (which are called fire temples). These fires are fed with pure fuel as a way to symbolize the asha inside a person. Just like an individual is kept morally good if he thinks about positive things, the fire also remains pure if fed clean and pure fuel sources. In Zoroastrianism, five types of fire are present throughout creation. These can be found in inanimate matter, living bodies, plants, clouds, and flame and are all remnants of the original fire that the Zoroastrians believe created the universe. Though fire plays a central role in their religion, they do not worship the fire itself as is commonly believed. Rather, the fire is a tool and a symbol used by God to create and maintain the universe and all its life.[5]

5 Fire Isn’t Just Orange

Most common fires, such as campfires, burn between 590–1,200 degrees Celsius (1,100-2,200 °F). This temperature results in an orange flame. At this temperature, some carbon from the fire’s fuel escapes without being burned. These trace elements are mixed with the fire and illuminated by its light and give the fire a yellow or orange glow. But this changes when a fire increases in temperature. At 1,260–1,650 degrees Celsius (2,300–3,000 °F), the fire is hot enough to consume all the carbon. With no surviving carbon particles to change the color, these hotter fires (like the ones produced from a propane stove) burn a brilliant light blue. But carbon isn’t the only kind of chemical or compound that can end up in a fire. If a fuel source is burned that has small amounts of copper, those copper particles will enter the fire and produce a green light in the same way that carbon particles produce orange.[6] When burned, lithium chloride produces a pink flame, strontium chloride makes red, and potassium chloride creates purple. A rainbow of colors is possible depending on the kind of fuel burned.

4 Fires Can Be Started With Ice

Fire and ice are usually considered polar opposites—and for good reason. Few things can exist as far apart on a spectrum as fire and ice do in terms of temperature, but enterprising survivalists have devised ways to use one to create the other. As unlikely as it seems, ice could be the key to staying warm when stranded in winter. The method requires using a knife to carve out a roughly circular piece of ice. Then that disk is further polished using the warmth from human hands. Eventually, a lens can be formed—like a magnifying glass. At this point, the ice lens can be used to focus sunlight into a narrow beam which heats up dry tinder and can be coaxed into a fire. This method takes a lot of time and finesse. But if you’re stranded in winter, it makes use of one of your most abundant and unlikely fire-starting resources.[7]

3 The Eucalyptus Tree Loves Fire

Every year, an average of 67,000 forest fires rage all over the world, and they consume roughly seven million acres of land. Few things are spared, and whole ecosystems can be wiped out in the blaze, including entire forests. Fire is one of a forest’s most powerful natural enemies. Yet there’s one tree in particular that not only easily survives fires but actively promotes them. The eucalyptus tree of Australia, which grows 18–55 meters (60—180 ft) tall depending on the species, is designed for fire. Their fallen leaves make a perfect flammable blanket, and their bark peels off in long stripes that reach to the ground. This allows fire to climb up and into the branches. “Crown fires” that travel up into the canopy and burn branches and leaves are common. The oil of a eucalyptus tree, known for giving it a fragrant smell, is also highly flammable and has earned the species the nickname “gasoline tree.” But why would a tree be designed to encourage fire to burn it? Their seed capsules are perfectly suited to crack open in a fire, and the seeds grow quickly in the ash-rich soil after a fire. “Give a hillside a really good torching, and the eucalyptus will absolutely dominate,” said David Bowman, a forest ecologist with the University of Tasmania. “They’ll grow intensively in the first few years of life and outcompete everything.”[8] The eucalyptus tree’s love of fire has been a large cause for concern in Australia where the nature of the tree has created many powerful fires. But the eucalyptus tree was imported to every inhabited continent, and now its fire-loving ways are spreading the danger elsewhere. “What the hell have humans done?” Bowman asked. “We’ve spread a dangerous plant all over the world.”

2 Flamethrowers Have Existed Since Ancient Times

Weaponized fire has a long history in warfare. The use of intentional fires against enemies dates at least as far back as 3500 BC. The peoples from northern and southern Mesopotamia were in conflict, and a settlement was intentionally burned (and bombarded with sling bullets). But sophisticated use of fire isn’t something that we think of as commonplace in warfare until it was introduced to the German army in 1901 and employed in World War I. However, the truth is that flamethrowers, machines designed to project a burning liquid over great distances, have been in use since ancient times and were very advanced even then. During the reign of Byzantine Emperor Constantine IV around AD 668–685, a Greek-speaking inventor named Callinicus of Heliopolis designed what would eventually become known as “Greek fire.” This handheld weapon could ignite and launch a special burning compound, which was instrumental in the defense of the Byzantine Empire for hundreds of years. In fact, it was one of three things that Emperor Romanos II, who ruled as senior emperor from AD 959–963, declared must never be allowed to fall into foreign hands. (The other two were any Byzantine imperial regalia and any royal princess.) Originally, Greek fire was mostly used in navel combat to burn enemy ships because the compound could not be extinguished with water. In fact, it was reported to burn especially well against water. Eventually, it was also employed during sieges in the form of portable pumps that could be used both against or in defense of a city. Liutprand of Cremona, a diplomat and historian who was alive during the use of Greek fire, described it by saying, “The Greeks began to fling their fire all around; and the Rusii, seeing the flames, threw themselves in haste from their ships, preferring to be drowned in the water rather than burned alive in the fire.”[9]

1 Fire Is Used As Medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine is a huge industry worth about $84 billion as of 2012. It employs such tactics as acupuncture and suction cups as well as unusual ingredients like caterpillar fungus and dried gecko. But one method of treatment is gaining more attention as of late: “fire therapy.” This is purported to treat many chronic ailments. Supposedly, it lessens wrinkles and restores youthful energy. It’s based on Chinese folklore that says good health is a result of balance between the “hot” and “cold” elements present within a human body. The treatment involves the use of an herbal paste, an alcohol-soaked towel, and a lighter to start a controlled fire at key pressure points of the human body. One of China’s prominent fire therapists, Zhang Fenghao, said, “Medicine needs a revolution. Fire therapy for the world is the solution.”[10] As of yet, fire therapy has neither certification from medical journals nor empirical evidence to back up its claimed health benefits. It’s also dangerous.