Some items prove that certain things never change—people cheated at games, carried deadly weapons, and were addicted to cheese. Medieval artifacts also preserved the era’s weirder moments, like the three-person toilet and the nun who escaped her convent by faking her own death.

10 Medieval Peasant Diet

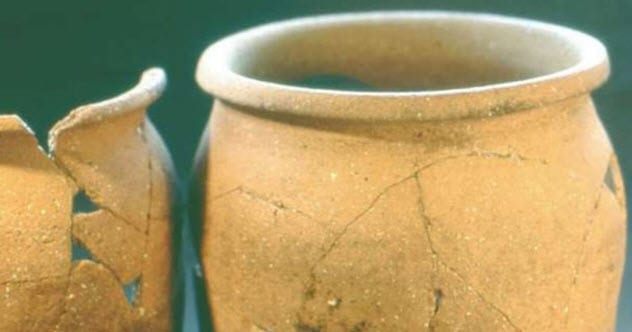

When it comes to medieval munchies, the diets of the English nobility are well-known. The menu of the peasantry, however, was so poorly recorded that researchers were not sure what people ate. Their mainstay was probably pottages and stews, but there was no direct evidence to prove this. In 2019, 73 cooking pots underwent chemical analysis to test for food residues. The 500-year-old vessels came from a medieval village called West Cotton. Fat showed up in many of the jars, confirming that ceramics were important in the medieval kitchen and that peasants did rely on stews and pottages as a staple. Ingredients included meat like mutton and beef. There were also traces of leafy vegetables such as cabbage and leek. The meat-cabbage stew was an important find. Nothing similar had shown up in elite kitchens. Although the greatest surprise was a lack of fish, the vessels did betray the villagers’ love of dairy. Almost a quarter of all the pots were used for milk-derived products. When this new information was consolidated with animal remains at West Cotton, scientists were able to compile a “cookbook,” which described meals, butchery and preparation techniques, and the disposal of scraps.[1]

9 The Aberdeenshire Game Board

The oldest Scottish manuscript is believed to be the Book of Deer. Written by monks during the 10th century, the illuminated book contains the earliest Gaelic writing from Scotland. Archaeologists have been looking for the authors’ monastery since 2008. It was fittingly called the Monastery of Deer and was located somewhere in Aberdeenshire. In 2018, a team were excavating newly discovered ruins when they found a gaming board. In itself, the artifact was a scarce find. It was shaped from stone to resemble a disk, and its motifs suggested that it was used to play a range of games popular in medieval Ireland and Scandinavia. What got archaeologists excited were the layers beneath the artifact. They dated to the seventh and eighth centuries, the same as pieces of charcoal found at the site. This proved that at least some of the ruins were in use—with people playing a game—during that time.[2]

8 The Missing Nun

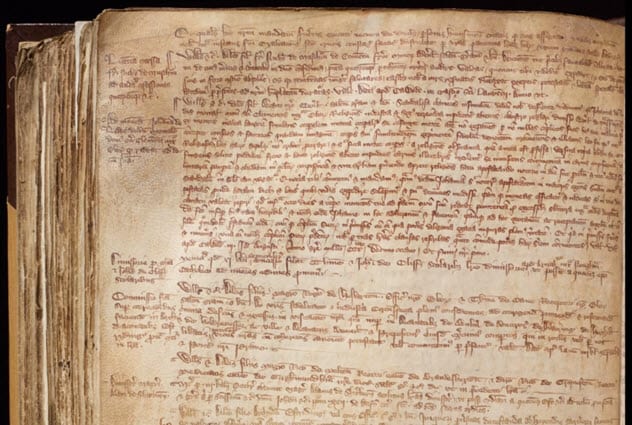

In recent times, historians riffled through the Registers of the Archbishops of York. The tomes recorded the dealings of archbishops from 1304 to 1405. A new project aimed to create an online version of the registers, and during the process, researchers encountered a letter. Dated 1318, it was written by Archbishop William Melton who recounted a “scandalous rumor” he had been told. Apparently, a nun named Joan had escaped her convent. Not only did she run, but she tried to fake her own death. Apparently, she created a body double to take her place at a funeral. Since people were buried in shrouds back then, Joan might have stuffed a shroud and shaped it like a corpse. The reason for her escape was given as “carnal lust,” which could have been anything from a desire to live in the outside world to wanting to get married. The letter was addressed to the Dean of Beverley, who was stationed in Yorkshire about 64 kilometers (40 mi) away from York. The dean was asked to find and return the wayward nun to her convent in York. Thus far, there is no clue about whether Joan managed to dodge the dean.[3]

7 The Sewer Sword

Early in 2019, engineers and construction workers toiled within a sewer. The idea was to install pipes in the city of Aalborg, Denmark. Instead, workers found a double-edged sword. The artifact was taken to archaeologists, who inspected the 1.1-meter-long (3.6 ft) weapon. The verdict was a happy one. Not only was it found in an unusual place, but it also likely belonged to an elite soldier. During the 1300s from whence it came, only the nobility could afford to commission these expensive weapons. The odd place it was discovered had nothing to do with the sewer. It was found on some of Aalborg’s oldest pavement. The sword, which was still sharp and deadly, showed signs of at least three battles. This suggested that it might have been forged centuries before ending up on the pavement. Its exact age has not been agreed upon—only that an elite warrior owned it in the 1300s. Aalborg saw its fair share of storming hordes, and the weapon was probably lost when its owner attacked or defended the city.[4]

6 The Bergen Dice

In 2018, archaeologists explored Bergen in Norway. While excavating in the Vagsbunnen district, they found a wooden cube next to a street from the Middle Ages. Since each side of the cube had dots, the block was quickly identified as a dice (aka die). Bergen had already produced over 30 dice from medieval times, so nobody was stunned—at first. Before long, it became clear that the dice was abnormal. The 600-year-old artifact lacked the sides for 1 and 2. There were sides with 3 to 6 dots, but in the place of the missing numbers were an extra 4 and 5. The area once hosted many pubs and inns, and their clientele probably enjoyed gambling. In a game of chance, this dice would have given its owner an unfair advantage. Alternatively, it could have been thrown during a game that never used 1 and 2. However, archaeologists are almost certain that somebody crafted the cube to help them cheat.[5]

5 A Lewis Warder

In 1831, the pieces of four medieval chess sets were found on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland. Carved from walrus tusk, the collection became known as the “Lewis hoard.” The tiny figures’ clothing and gestures offered researchers valuable glimpses into medieval society, but there was something else that would have made them even happier. The chess sets are not complete. Five pieces had never been found. In 1964, an antique business purchased a small statue. The owner described the acquisition in his records as an “antique walrus tusk warrior chessman.” He ought to have known. However, the piece was passed down in the Edinburgh family for 55 years and recently brought to the auction house Sotheby’s for appraisal. It was positively identified as one of the missing Lewis artifacts. It was a warder, which in modern chess would be a rook or castle. The figure wore a frown, brandished a sword, and, for some reason, was darker than the rest of the Lewis pieces. Incredibly, the antique dealer bought it for £5 but the real worth is almost £1 million ($1.3 million).[6]

4 Three-Person Toilet

One might not consider a toilet rare, but one 12th-century example fits the bill. Around 900 years ago, somebody took an axe and hacked three holes into a large oak plank. This three-person toilet seat was then positioned over a cesspit near the Thames. Back in the day, it stood behind—and probably served—a building that was located at the modern-day Ludgate Hill. Researchers managed to track down some of the names of the people who lived and worked at the building, which contained a mixture of homes and businesses. Among the names were Cassandra de Flete and her husband, John, a capmaker. The building itself was called Helle when the loo was in use. Adventurous scientists decided to sit on the seat, which was discovered in the 1980s. Although they found the axe-hewn holes comfortable, personal space was an issue. The holes were close together, and three people using the facilities would have sat shoulder to shoulder.[7]

3 Lost Govan Stones

Between the 10th and 11th centuries, gravestones were carved in the Kingdom of Strathclyde. The latter was one of several powers that fought to gain control over the British Isles when Scotland did not yet exist. The stones were large and beautifully decorated. In the 19th century, 46 were unearthed in Glasgow and became known as the Govan Stones. Eventually, 31 were relocated to the Govan Old Parish Church. This included a stone-carved sarcophagus that was said to have held the remains of a saint-king called Constantine. The rest were displayed for years against a churchyard wall but vanished when a nearby shipyard was demolished. For over 40 years, historians feared the valuable stones had been destroyed.[8] In 2019, an archaeological dig brought experts and volunteers together to search for the missing gravestones. A 14-year-old schoolboy struck gold. While digging near the Govan Parish Church, he found a Govan Stone. This led to a more intensive search, and two more were found. The discovery offers some hope that the rest of the missing sculptures will surface in the future.

2 Traveling Book Coffer

These days, bookworms can carry a library on their phones. Since medieval readers did not have the luxury of .pdf files, travelers often used a book coffer. Today, only about 100 of these rare artifacts remain. In 2019, Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries acquired one from a private buyer. The case came from France and had been constructed of wood and leather during the 1400s. It also had metal clasps and hand straps for carrying. The box was exceptionally valuable for two reasons. Most surviving book coffers date from the 1500s, which makes this one of the oldest ever found. The most exciting find was a woodcut attached to the inside of the lid. It was a piece called “God the Father in Majesty,” a draft that originated from a liturgical book in Paris. The Bodleian suspect that the print was used as spiritual protection for the coffer’s content. Overall, the woodcut was incredibly rare. Not only was it found in its original context and dated to Europe’s earliest attempts at printing, but only four of its type are known to exist.[9]

1 Royal Marriage Bed

Almost a decade ago, an antique dealer bought a bed online. Ian Coulson from England liked the catalog’s description of a “profusely carved Victorian four-poster bed with armorial shields.” After Coulson brought it home, he realized the description was inaccurate. Luckily, he had not been fleeced. Instead, the dealer had stumbled upon what could be the most important furniture in England. Moreover, the most important royal artifact—the “armorial shields”—was the English royal coat of arms. Along with Coulson, several experts believe that the bed is not Victorian at all. The timber was worked with hand tools, which placed it in a medieval workshop and not the mechanized factories of the industrialized Victorians. The bed also had traces of ultramarine, a medieval pigment more expensive than gold. This proved the bed belonged to a high-status couple sometime during the 15th century.[10] Since the bed’s carvings included the roses of the houses of York and Lancashire, the couple was likely King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. Their bed was commissioned before the wedding, and it vanished during the English Civil War when parliamentarians destroyed all royal furnishings. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages