Lady Hester was born into the heart of the English establishment, daughter of the 3rd Earl Stanhope and niece to the future Prime Minister, Pitt the Younger. Lady Hester’s wanderlust manifested early in life when she tried to row a small boat to France, but was soon recaptured. An active and intelligent young lady, she was chosen to act as hostess for the unmarried Prime Minister at official events, and would later serve as his secretary. After Pitt’s death, Lady Hester was awarded a substantial pension from the nation for her service. It was this income which gave her the freedom to travel. She set sail for Athens, where Lord Byron swam to her ship to welcome her, with a plan to work her way back to Paris and spy on Napoleon. British diplomats put a stop to this and so Lady Hester and her small household set out for Egypt. When their ship foundered off Rhodes, Hester was reduced to wearing men’s clothing, a habit she took up from that point onwards. Now began Lady Hester’s Middle Eastern exploits. She met with the ruler of Egypt, dealt with bandits, visited biblical sites, and by receiving Arab hospitality, began to believe herself a Queen to the locals. Lady Hester was the first European to visit several cities and was warmly received by their rulers. In the ruined city of Palmyra, Lady Hester imagined she had been crowned Queen of the desert, and could never be shaken from this belief. She spent her final years bricked up in a palace in the mountains of Lebanon.

Peck achieved academic success in her twenties as she received degrees in philology and showed a particular aptitude for ancient Greek. This led to her becoming one of the first female professors in North America. Peck spent time studying archaeology at the American School of Classical Studies, in Greece, the first woman to do so. She seemed to have settled happily into an academic career. However, when she was 44, Peck took up mountain climbing while in Europe, becoming the third woman to scale the Matterhorn. Returning to America she spent time climbing in South America, specifically searching for the highest mountain in the New World. Peck mistakenly thought she had achieved this when she became the first person to climb Mount Huascarán. The northern peak was later renamed in her honor. She wrote and lectured extensively about her adventures and continued to climb into old age. In 1909, when Peck climbed Mount Coropuna in Peru, she planted a flag on the summit which read ‘Votes for women!’

Gudridur (or Guðríður) was born around 980AD in Iceland, and her life story comes to us from the great Icelandic sagas. From Iceland she was to travel over a far greater distance than most other people of the age. Gudridur was taken by her father to the colony on Greenland founded by Erik the Red, and married Thorstein, Erik’s son. Together with her husband she joined the expedition west of Greenland to a place called Vinland, now known to be North America, to recover Thorstein’s brother’s body. Unfortunately, this expedition was a failure and on the return trip Thorstein, himself, died. In Greenland she married again. With her new husband, Thorfinnr, they made another attempt at colonizing Vinland. The two years that this colony in the New World lasted are documented in the Greenland Saga. While there, Gudridur gave birth to the first European child in the New World; her son Snorri. The Greenland saga tells of strange people, whom the colonists call Skraelings, indigenous to the area. At first the Norse traded with the Skraelings, but later a fight occurred, which the Norse win. In fear of a greater attack, the Norse retreated to Greenland. At some point, Gudridur converted to Christianity, along with the rest of the Norse. When her husband died, Gudridur decided to take a pilgrimage to Rome. While there she met the Pope and told him of her adventures. Returning to Greenland she became a nun and lived the rest of her life as a hermit.

Adams gained her love of the outdoors from her father who, lacking sons, took Harriet riding and walking in the mountains. Aged fourteen she accompanied her father on a yearlong trip by horse through the Mexican border-lands. When she married Frank Adams, the couple decided not to take a honeymoon until they could afford to travel somewhere exciting. Frank, an engineer, was offered a job in Mexico, and the two turned this work into an extended honeymoon. Harriet visited all of the ruins of the Aztecs and Mayans, many only recently discovered in the forests. Harriet became enamored with Latin America and encouraged Franklin to take up a post with a mining corporation which would allow them, and more importantly pay them, to travel throughout South America. Wanting to document their travels, Harriet learned to take photographs. It would be her stunning photos and ability to enthrall audiences with her experiences which would turn Adams into one of the foremost explorers of her day. She turned her travels into articles for magazines and delivered lecture series. She is best known for her South American explorations, but she also visited Asia and, on the outbreak of the First World War, became a war correspondent. Since the Geographical Society did not allow women to be full members, she helped found, and served as first president of, The Society of Woman Geographers.

In her obituary, Freya Stark was called ‘the last of the Romantic travelers.’ This reputation has cemented her position as one of the best loved travel writers in English, and her long life held plenty of adventure. Her early life was spent in Italy, though she was confined by illness for long periods. After an accident where her hair became caught in machinery, she required months of skin grafts which kept her in hospital. Stark spent her time reading and teaching herself Latin. Her traveling life began in the late 1920s, and she was a restless soul from then on. Her second book, The Valleys of the Assassins, tells how Freya Stark became the first European woman to enter Luristan, in Iran. In the mountains, she mapped out the area for westerners for the first time and saw the ruined castles of the Assassins. Returning from this adventure, she published the first of nearly thirty books on travel that are still read today. The Second World War found her knowledge of the Middle East and languages put to good use in combating fascism. In Egypt, she founded a pro-democracy political group to counter the fascist propaganda being spread by German agents. After the war, she continued her travels and writing, for which she was made a Dame, in 1974. She continued traveling until the end of her life, often descending on friends whose homes she would commandeer.

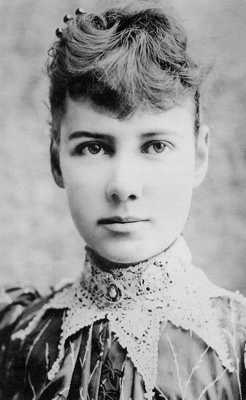

Nellie Bly may be the most recognized name on this list, but she was born Elizabeth Cochran. Her adventures came about due to her work for the New York World paper. This was the age of ‘stunt’ journalism, and Bly’s first report was to be an exposé of a women’s lunatic asylum. Pretending to be demented, Bly was admitted and experienced the lot of the patients confined on the island. The food was rancid, the nurses brutal, and the asylum hardly fit for humans. The article she wrote was a breakthrough in investigative journalism, and led to reform for mental hospitals. Her next adventure was one that brought her worldwide fame. Bly undertook a challenge to make a trip around the world in a time faster than Phileas Fogg’s eighty days. She set out with a special passport signed by the Secretary of State, on November 14, 1889. Her voyage started in seasickness but would end in triumph. In France, she met Jules Verne, who thought she might manage the trip in 79 days, but never the 75 she hoped. Having steamed across seas, gone through the Suez Canal, seen Colombo and Aden, visited a Chinese leper colony and bought a Monkey, Bly made it back to New York in a time of 72 days, 6 hours and 11 minutes.

Born into wealth, Louise Boyd would use her large inheritance to explore the Arctic regions she loved so much. Boyd would be the first woman to reach the North Pole, in the relative comfort of an airplane, in 1955. Traveling to Europe after the deaths of her parents, in 1920, she spent some time in Spitsbergen where she found the ice beguiling. Her first Arctic exploration was in 1926 when she spent time filming and photographing the environment of the Arctic. It was her hunting of Polar bears on this trip which earned her the nickname ‘Diana of the Arctic.’ Her most famous exploit was assisting in the hunt for famed Antarctic explorer Roald Amundsen, who had disappeared while aiding a downed Italian airship. Her plane covered ten thousand miles in the search, but Amundsen was never found. For her efforts, Boyd became the first non-Norwegian woman to be awarded the Chevalier Cross of the Order of Saint Olav, by King Haakon VII. She returned to the US and led five expeditions in Greenland, for which she was honored by the Geographical Society, and an area of Greenland was named Louise Boyd Land in her honor.

The Golden age of adventure for women may seem to have passed, but there is still a big world out there to document. Kira Salak is a writer and professional adventurer. After graduating with a PhD in literature and travel writing, she traversed Papua New Guinea. This experience she turned into the book Four Corners. Since then, she has written numerous articles and visited Peru, Iran, Bhutan, Mali, Libya and Burma, amongst others. Perhaps her most daring exploit was in the Congo on the trail of mountain gorillas. Salak was smuggled into the country by Ukrainian gun runners. The award-winning article she wrote about this trip gives a clear insight into a country with many human problems, but also the attempts to keep alive the mountain gorillas. In the town of Bunia Salak met with some of the child soldiers of the local militias. There is none of the charm of the British Victorian adventuresses in her writing, but then the things Salak reports often leave little room for such ornament. Salak’s less shocking travels reveal a world which we, living in an age of easy travel, are far more able to explore if we only have the thirst for knowledge and adventure.

Mary Kingsley was never formally educated, but aided her traveler father in his research. Her father put her to work taking notes for his study of comparative religion, but when he died this was left unfinished. Lacking any direction, but with an inheritance in hand, Kingsley decided to continue her father’s work by studying the religions of West Africa. When she asked experts where she should travel and what she should do, Kingsley was advised not to go at all, but if she did go they asked her to bring back biological samples. So she set off with a small amount of luggage, collecting cases for samples, and a phrase book with such helpful phrases as “Get up, you lazy scamps!” Despite these limitations, Kingsley made two trips to West Africa and described them in her book ‘Travels in Africa.’ She did return some interesting flora and fauna to Britain and three species of fish were named in her honor, but the real importance of her journeys were in spreading a somewhat more enlightened view of Africa than existed at the time. The natives, she said in her lecture tours, we not savages waiting to be brought up to European standards, but had independent minds and cultures of their own. She died in South Africa of typhoid, while treating the wounded in the second Boer war.

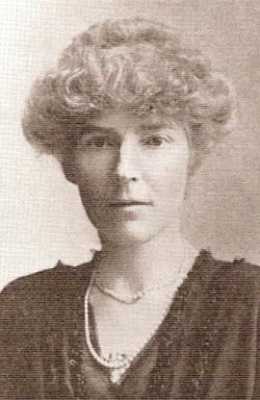

Gertrude Bell was many things in her life but is best remembered today for her role in shaping the nation of Iraq after the First World War. Bell was to have many firsts to her name; she was the first woman to receive a first class degree in History from Oxford, and the first woman to write a white paper for the British government. She traveled around the world twice. Once, while mountaineering in Switzerland, she was caught in a blizzard and spent two days hanging from a rope. Bell’s true calling came when she traveled to Tehran to visit her uncle. In the Middle East she taught herself the local languages and studied archaeology. Many archaeologists of the Middle East at the time were also serving as scouting intelligence agents, like T. E. Lawrence, whom she met at a dig. In 1915, she worked with Lawrence again in Cairo for the British Arab Bureau. Bell’s knowledge of the Middle East was used to help British army movements. When she went to Basra she made contacts with many important locals. Bell also met the future kings Abdullah and Faisal. At the post-war conference on the British mandate in the Middle East, Bell pushed hard for self-rule and helped to advise King Faisal. She is buried in Baghdad, the capital of a country she helped create.