It may seem odd to have a computer among the greatest chess players, but that’s exactly what this machine was designed to do, play chess. The rivalry between Kasparov and IBM began in 1989 but it wasn’t until May 11, 1997, that Deep Blue finally succeeded in defeating the then World Champion Garry Kasparov in a 6 game match. It won 2, lost 1 and had 3 draws after being defeated by Kasparov the previous year, though 1996 was the first year a computer actually won a game against a reigning World Champion. The win shocked the world, as it dawned upon us that we had succeeded in creating machines that could outthink us. Kasparov accused IBM of cheating, claiming IBM had chess players intervene during the match. IBM denied the allegations. Kasparov challenged them to a rematch, but IBM refused and dismantled Deep Blue. Nowadays, computers are regularly used by professional chess players as training partners and there are even World Championships for Chess Programs. It is that contribution that leads me to put Deep Blue on this list.

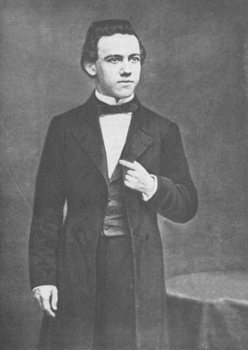

Many have claimed that Paul Morphy was the greatest chess player in history, and those claims could have been proven true had he actually pursued a career in chess. After teaching himself the game as a child by watching family members play, he was considered one of the best players in New Orleans by age 9. He famously played General Winfield Scott in 1846, who thought he was being made fun of when Morphy was introduced as his opponent. Morphy went on to easily defeat him in two games, the second of which was effectively over after only 6 moves. At age 12, he defeated the visiting Hungarian Master Johann Lowenthal in 3 matches, who initially viewed the match as a waste of time. In 1857, Morphy participated in the First American Chess Congress, which he won comfortably and was considered the champion of the United States. Too young to pursue his career in Law, Morphy travelled to Europe. By 1858, he had defeated all the English masters, except Staunton, who declined after seeing the young prodigy play. Next he travelled to France where he easily defeated the leading European player, Adolf Andersson, despite being very ill with intestinal influenza. He won 7, lost 2 and drew 2 and was by then considered the strongest player in the world, despite being only 21. Morphy returned home and retired from chess, only playing very occasional games. Had he pursued his career further, there is no doubt that Paul Morphy would be a contender for the number one spot. He was arguably the most gifted chess player to have ever lived, years ahead of his time in play and theory.

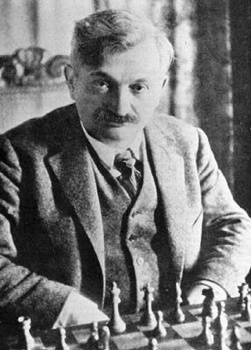

A lifelong Communist, Mikhail Botvinnik held the World Championship on and off for 15 years, from 1948 to 1963 when he was eventually defeated. Not only a great player, he made significant contributions to developing the World Chess Championship after WW2. He also coached some of the greats, including Anatoly Karpov, Garry Kasparov and Vladimir Kramnik. He learned chess at the age of 12 and within a year had won his school championships. In 1925, he defeated the great Capablanca in an exhibition game, though the Cuban was playing simultaneous matches. In 1931, at only 20, he became the Soviet Champion, scoring 13.5/20, no mean feat considering the enormous chess talent to come out of the nation. He then went on to tie a match with Flohr, considered the number one challenger for Alekhine’s World Championship crown. By the mid 1930’s, Botvinnik was holding his own against the greatest players in the world, finishing strongly in many tournaments. The outbreak of WW2 prevented him challenging Alekhine for World Champion in 1939. In the early 1940’s, he won the right to challenge Alekhine by defeating a strong Soviet field for the title of “Absolute Champion of USSR,” however it never eventuated with Alekhine’s death in 1946. He won the newly formatted title in 1948, with a score of 14/20 against 4 of the world’s best players. Botvinnik defended it in 1951 with a draw against David Bronstein, then again in 1954 with another draw against Smyslov, until his defeat in 1957 against the same opponent. He won a rematch in 1958, before losing the title again to Mikhail Tal in 1960, then winning the rematch in 1961. Finally he lost it for the final time in 1963 to Tigran Petrosian. He retired from competitive play in 1970, where he devoted himself to the development of computer chess programs and training young Soviet players.

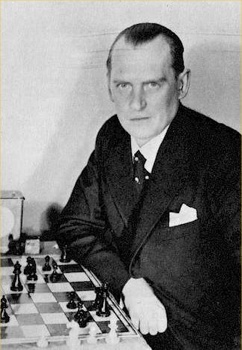

Alexander Alekhine won his first World Championship by defeating the legendary Jose Capablanca in 1927. At the age of 16, he was already one of Russia’s strongest players and by age 22 was considered one of the strongest players in the world, winning most tournaments he played in throughout the 1920’s and was dominating tournament play by the early 1930’s. In 1921, he was granted permission to leave Russia for a visit to the West. He never returned. Alekhine’s biggest objective was winning the World Championship from Capablanca, though his largest challenge was raising the $10,000 stakes required for a successful challenge under the London rules. He gave exhibitions of simultaneous blindfold games to try and raise the stakes, but was eventually backed by Argentinean businessmen who financed his challenge in 1927. He defeated Capablanca with 6 wins, 3 losses and 25 draws, the longest ever World Championship match until 1984. The victory shocked the chess world (including Alekhine himself), considering he had never previously won a game against Capablanca. Negotiations for a rematch dragged out for years, and never eventuated. The two became bitter rivals. Alekhine dominated international chess for the next decade, until alcoholism resulted in a noticeable decline of his abilities. Alekhine successfully defended his title against Bogoljubov in 1929 and 1934, but lost the title to Euwe in 1935. He regained it in 1937 in a rematch and held it until his death in 1946, largely due to WW2 making international chess matches virtually impossible to organise. After WW2, he was not invited to tournaments due to his alleged Nazi affiliation, though evidence suggests this was largely pragmatic.

Another player who has claims to the greatest of all time, Bobby Fischer’s worst opponent was usually himself. Beginning at age 14, Fischer won 8 US Championships, including the 1963-64 Tournament 11-0, the only perfect score in its history. By 15, he was the youngest ever Grandmaster (GM) and the youngest ever candidate for the World Championship. By the early 1970’s, he was dominating his peers on the chess board, winning 20 consecutive matches in the 1970 Interzonal. By 1972, he had won the World Championship from Boris Spassky (his biggest rival) of the Soviet Union. Many viewed this match as an extension of the Cold War. In 1975, Fischer did not defend his title due to an inability to agree on conditions with FIDE, the International Chess Federation responsible for professional chess worldwide. He became a recluse and retired from international chess, with one exception in 1992, where he played Spassky again for a reported $5,000,000 purse. This event ultimately led to an arrest warrant being issued for Fischer and he never returned to the United States. In later years, Fischer came into further conflict with his own government, often publicly making anti-American and anti-Jewish statements. When his passport was eventually revoked and he was held in Japan for 9 months under threat of extradition, Iceland granted him citizenship, where he lived until his death 3 years later. No player before or since has had such a large margin between themselves and their rivals as Fischer did in the early 1970’s and had it not been for his constant demands over playing conditions and money in World Championship matches, and his relatively brief career, he too could have been a contender for the number one spot.

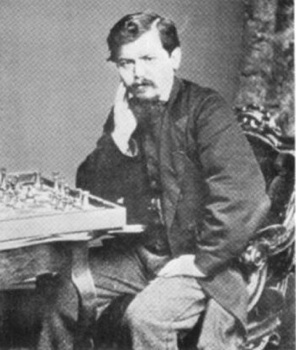

Jose Capablanca was World Champion from 1921-1927, and is often considered a candidate for the greatest player in history. He was also the undisputed master of Blitz Chess (5 minutes per side). He learned the rules by age 4, and at age 13 he narrowly defeated the Cuban champion. In 1906, aged 18, he crushed US champion Frank Marshall 15-8. In the San Sebastian 1911 tournament, he stunned the chess world by defeating an extremely strong field with 6 wins, 1 loss and 7 draws. He was now recognised as a serious contender for the World Title, held by Emanuel Lasker. He challenged Lasker, but refused to agree to 17 conditions placed on the match by the Champion, many of which favoured Lasker. Finally, in 1921, they agreed on terms and Capablanca won the Championship relatively easily without losing a game. He then set about formalizing the World Championship rules (known as the London rules) to which all the leading players agreed to. In 1922, he gave a simultaneous performance against 103 opponents, winning 102 and drawing 1. From 1916-1924, he lost only 34 serious games including a run of 63 games undefeated, an incredible feat. By 1927, Alexander Alekhine had finally come up with the $10,000 needed to challenge for the World Title. Capablanca was confident of victory, as he had never lost to Alekhine, however he was defeated and lost his title, never to regain it. They did not appear together in another tournament until 1936. After losing the title, Capablanca played in more tournaments, hoping to gain a rematch but he was past his peak form, which he claimed was 1919. Errors began to creep into his game, and he slowed down considerably. He retired from serious chess in 1931, however he returned in 1934, determined to regain the title. While he had some good successes and showed he was still a world class player, he never managed to secure another chance at the title.

Wilhelm Steinitz spent 8 years as the reigning World Champion (1886-1894), though some chess historians describe him as Champion from 1866 onwards, when he defeated Adolf Andersson. Steinitz rightly deserves his place on this list not only for his World Championships, but the contribution he made to the development of modern chess. In 1873 he unveiled a new style of positional play that sharply differed from the traditional method of all out attack, and many branded it cowardly. However, by the early 1890’s it was widely considered as superior and was being used by the next generation of players. By his early 20’s, Steinitz was playing chess professionally throughout Europe, and many branded him as the “Austrian Morphy.” He moved to London in 1862 and defeated all the leading players there. His breakthrough came in 1866, where he defeated Adolf Andersson, then considered the strongest active player in the world after the retirement of Morphy. Steinitz spent 30 years at the pinnacle of the chess world, a feat of longevity unmatched by any other player, though from 1873 to 1882 he only played one competitive match, against Blackburne, which he won 7-0. He returned to competitive chess in 1882, where he finished equal first in what was considered the strongest tournament ever held. In 1886, he played his bitter rival Zukertort for the “Championship of the World” After a shaky start where he was trailing 4-1, Steinitz finished brilliantly to take the crown 12.5/7.5. Over the next 8 years, Steinitz successfully defended his crown by defeating Gunsberg and Chigorin before finally losing it to Emanuel Lasker in 1894 and unsuccessfully challenging again in 1897. Not only did Steinitz contribute greatly to the development of modern chess, he also worked hard to standardize World Championship matches. Unfortunately, he died in poverty in 1900. A sad end to a great champion.

Emanuel Lasker dominated the chess world and spent an incredible 27 years as World Champion, the longest ever. He contributed greatly to chess becoming a professional career by demanding high fees for his appearances. He began to make his mark in 1889, winning several tournaments and in 1893 won 13/13 in a New York tournament, one of the few perfect scores amongst a strong field in history. By 1894, he had a chance to win the World Title from Steinitz, which he promptly proceeded to do with 10 wins, 5 losses and 4 draws. This began his 27 year reign as World Champion. His rivals criticized him for beating an old man and denounced his victory. Lasker responded by putting in even stronger tournament performances. He defended his title in 1907 against Marshall without losing a game and then in 1908 defeated his hated rival Tarrasch in another Championship defence with 8 wins, 5 draws and 3 losses. Tarrasch blamed his defeat on the wet weather. In 1910 it was first Schlechter (who narrowly lost) and then Janawski who challenged Lasker for the crown but they both failed and the latter didn’t win a single game. In 1911, Capablanca attempted to challenge Lasker, however the German put such stringent conditions on the game that Capablanca withdrew from negotiations. WW1 put an end to any further World Championship defences. He was finally defeated by Capablanca in 1921. He was 53 at the time, well past his prime and never played another serious match until 1934 when he took up Soviet citizenship. At age 66, he finished 3rd in a very strong field in Moscow. It was hailed as a “biological miracle.” Throughout his career he constantly finished ahead of Capablanca in tournaments, despite his World Championship loss in1921. While he did not contribute a great deal to chess other than his natural brilliance, longevity and bigger purses, many Russian masters cite him as a major influence in their playing style.

Were it not for our number one, Anatoly Karpov would certainly go down as the greatest player in history. He was World Champion from 1975-1985, then from 1993-1999 (disputed) and still plays competitive chess to this day (ranked 98). He has over 160 first place tournament finishes to his name. Karpov learned the game at age 4, and joined Botvinnik’s prestigious chess school aged 12 and by 15 was a Soviet National Master, the youngest ever (tied with Spassky). In 1969, Karpov won the World Junior Chess Championship with a score of 10/11. In 1974 he surprised everyone, including himself by defeating Korchnoi and Spassky for the right to challenge Fischer for the World Title. After negotiations broke down, Fischer resigned his crown and Karpov became Champion by default. He went on to win an incredible 9 consecutive tournament victories. He successfully defended his title against Korchnoi in 1978 with a narrow victory then did so again more convincingly in 1981. In the Chess Olympiads, he lost only 2 games out of 68 throughout his career. Karpov’s last successful title defence was against Garry Kasparov in 1984 in an epic 48 game match (5 wins, 3 losses, 40 draws). The match was terminated for the health of the players (Karpov had lost 10kg in 5 months.) He lost the title the following year to Kasparov. Karpov launched 3 unsuccessful challenges in the next 5 years, narrowly losing all 3 in one of the greatest rivalries the chess world has ever witnessed. Karpov controversially regained the title in 1993 when Kasparov split from FIDE and attempted to start his own chess federation. He went on to win the 1995 Linares tournament, widely considered the strongest tournament in history, with an impressive 11/13 score. His tournament Elo rating of 2985 is the highest of any player in the history of the game. Karpov defended his World Title against Kamsky in 1996 but conceded it in 1999 in protest over FIDE rule changes to the way the Title was decided. Since then, he has played little chess, instead concentrating his life on a political career.

No other player has dominated as long or as strong as Garry Kasparov. His name is synonymous with chess. He became the youngest ever undisputed World Champion in 1985 at only 22, which he held until 1993 when a dispute with FIDE led him to set up his own organisation (PCA) and technically lost him the World Title, though most chess enthusiasts still considered him the unofficial World Champion during this period. It lasted until his loss to Kramnik in 2000. He was ranked number one almost continuously from 1986 until his retirement in 2005, which included the all time highest Elo rating of 2851, as well as a record 15 consecutive tournament victories. Kasparov began training at Mikhail Botvinnik’s chess school at age 10. In 1979, he was accidently entered into a professional tournament despite being unrated, which he duly won and by 1983 was ranked 2 in the world, behind World Champion Karpov. He challenged for the World Title and lost to Karpov in 1984 in an epic 48 game match (see entry on Karpov) but won the following year and successfully defended it 3 times against Karpov in the coming years by very tight margins. In 1993, Kasparov had a falling out with governing body FIDE. In 2007, Kasparov admitted that forming a breakaway organisation was the worst mistake of his career. The Title remained split for 13 years as Kasparov refused to rejoin FIDE. He lost the title to Kramnik in 2000. Even after losing the title, Kasparov continued to outperform his rivals winning a string of major titles and remained ranked number 1. He announced his retirement in 2005 after winning the prestigious Linares tournament for the ninth time, citing a lack of personal goals in chess. He is now pursuing a political career in his native Russia. Garry Kasparov completely dominated his peers for 20 years, and retired on top. He has contributed much to the theory of chess and rightly deserves the number 1 spot of greatest ever.