It might surprised us that branding has also been performed as an act of initiation and to identify prostitutes and criminals, mark status, protest, modify the body, provide medical treatment, warn others, and engage in sadomasochistic “play.” 10 Modern Torture Chambers

10 Punishment

In the sixteenth century, near Alzey, Germany, three-hundred-and-fifty heretics were put to death by order of the town’s military governor Dietrich of Schoonburg after the captive Anabaptists refused to recant of their faith. Others, who were spared death, were tortured, having their fingers cut off, having a brand in the shape of a cross burned into their foreheads, or receiving other “bodily punishment.”[1] In 1749, Mustafa Pasha, a former Ottoman prince who had been brought to Malta after being enslaved, led a conspiracy to overthrow his captors. With the assistance of Ottoman governors, he would free the island’s other slaves and seize Malta. When the plot was overheard and reported to Malta’s Grand Master Manuel Pinto da Fonseca, the conspirators were arrested, and thirty-eight of the leaders were tortured, condemned, and executed before their bodies were quartered and decapitated. Eight slaves were spared death, but their foreheads were branded with the letter “R,” for rebelli (rebel) and were consigned to the galleys for the rest of their days. Under the protection of the French king, Pasha himself escaped death and enslavement and was permitted to sail to Rhodes aboard a French ship.[2] Beginning in 1270, Russian authorities began to brand a variety of criminals. Although, at first, the punishment was rarely executed, thieves were sometimes branded on the cheek. In 1637, by court decree, branding was permitted to punish and identify counterfeiters. Later the same year, a special decree permitted the branding of robbers and thieves, the latter with the letters “T,” “A,” “T,” which stood for “tatba,” or theft.[3] Czar Peter the Great (1672-1725), who’d encountered branding in Europe, was impressed with the punitive measure, and the practice was extended to archers who were sent into exile and, in 1746, to all criminals as a means of identifying them should they escape. Initially, a double-eagle brand was used, but, during the eighteenth century, each criminal was branded on the back with a letter that represented the city in which he’d received the mark. During the rule of Empress Catherine the Great (1684-1727), an impostor, a priest, murderers, traitors, rebels, and others were also branded. The brands were impressed variously upon foreheads, cheeks, shoulder blades, arms, hands, and backs. In 1863, Emperor Alexander II (1818-1881) outlawed both branding and corporal punishment.

9 Initiation

Branding is featured in a Vaishnava initiation ceremony. Seals of the shanka (a conch shell with religious significance) and chakra (a disc with religious associations) were heated during a fire ritual before the ceremony. Then, an image of the chakra was stamped into the right arms of the faithful, and their left arms were branded with a representation of the shanka. Children usually receive the brands on their stomachs if they have yet to undergo the thread ceremony,[4] which is performed to ward off evil spirits from a bride and groom, to remind the groom of his three eternal debts (to his guru, his parents, and scholars), and to represent the virtues of strength, knowledge, and wealth embodied by the goddesses Parvati, Saraswati, and Lakshmi, respectively.[5]

8 Redefinition

Some members of the Black fraternity Omega Psi Phi opt to brand themselves. To each of the branded, the marks have personal meaning to them as individual African-American fraternity members. Warren Dews used four “hits” of a branding iron to create a pair of intersecting omegas on his left arm. The brand shows his profound affiliation with his fraternity brothers. Sam Ryan underwent branding in honor of his Boys Club mentor, an alum of Howard University, where he’d been branded in 1954, as a member of the same fraternity. Richard Pierre’s brand represents his ability to choose to be branded, as opposed to his ancestor’s having been forced to be branded, as slaves, without any choice in the matter, and is associated with his fraternity’s “association, achievement, and agency.” The men’s brands allow them to redefine branding as they make the marks of the iron represent their own intended, personal meanings.[6]

7 Prostitution

Pimps brand prostitutes to indicate that the streetwalkers are the procurers’ “property,” a practice which, police say, is becoming increasingly prevalent. Often, at first, the recipients of such brands see them as badges of honor, signifying that they belong to someone else, that they are members of a group, and as signs of their own commitments to their “owners.” Later, if she survives her pimp’s beatings and the drug addiction, attempted suicide, rape, and killers that go with the territory, a prostitute experiences the trauma and sense of brokenness that continue to haunt her.[7]

6 Public Slavery

In the ancient, medieval, and early modern worlds, private slaves were complemented by public slaves, among the latter of whom were galley slaves. Although neither the ancient Chinese or Romans, nor the Hellenistic Egyptians, routinely branded galley slaves, unless they repeatedly ran away, galley slaves were branded as a matter of course in Europe during the late Middle Ages and early modern days. In the middle of the sixteenth century, the French began branding the letters “G,” “A,” “L” into the shoulders of their galley slaves.[8] 10 Tantalizing Tales Of Tattoos Throughout History

5 Protest

269. That was their number, the number they had branded into their own flesh. By having these numerals seared into their biceps with hot irons, Israeli protesters signaled their identification with the dairy calf bearing this same set of digits as its identifying mark. In so doing, they also indicated their opposition to the slaughter and butchering of animals for human consumption and demonstrated their dedication to their cause. People who hoped to see the branding take place on the appointed day, at the appointed hour, were disappointed. Authorities’ threats of legal action dissuaded the protesters from carrying through with the branding—at least at the appointed place, during the appointed hour. Turns out that even voluntarily consenting to being branded constitutes the commission of an act of grievous bodily harm. Some of the vegans had kept their vows, however, allowing their friends to brand them in public the day before the advertised October 2, 2012, Tel Aviv protest. A spokesperson for the vegans admitted that the branding event was intended to gain attention, but claimed that the public branding, while extreme, was a “reaction” to the extreme slaughtering and butchering of newborn dairy calves.[9]

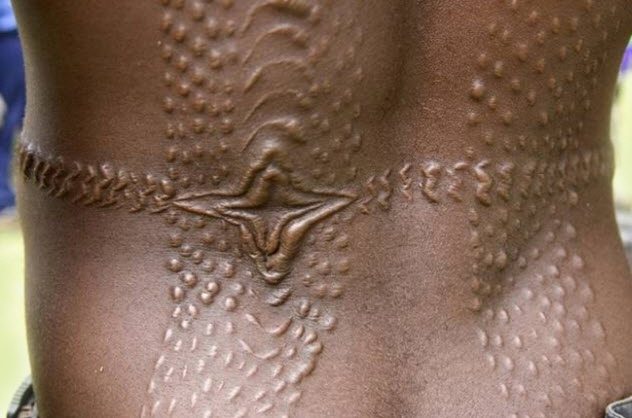

4 Body Modification

Branding is one way to produce scarification, a type of body modification used for adornment. Scarification can signify religious political, or social roles, and it is sometimes performed as a rite of passage to mark the onset of puberty. In addition, scarification, by branding or otherwise, can indicate affiliation, marking the bearer as a member of a particular tribe or social group. In addition, laser branding is used in body modification. In this high-tech version of scarification by branding, an electric pen is attached to an electrosurgical unit. Sparks from the pen “vaporize” the flesh, allowing precision work, while reducing damage to the skin and nearby tissue, causing less pain, and expediting healing.[10]

3 Cauterization

As early as the tenth century, Greek and Islamic physicians used hot irons, essentially brands, to cauterize wounds as a means of stopping bleeding, closing wounds, and preventing infections which, at the time, could easily have proved fatal. The expression on the face of a male patient shown in an eleventh-century medical manuscript concerning cautery leaves no doubt that the operation is a painful one. Ancient Greek medical texts recommend even more radical uses of cautery: a hot iron was advised as a remedy for both bladder stones and hemorrhoids![11]

2 Warning

Women who were “unruly” were thought to need special disciplinary measures. A nun, Madre Magdalena de San Jeronimo, advocated the construction of a special prison for Spanish women in need of punishment that was typically set aside for men. Felipe III was so convinced by her arguments that he not only built the women’s prison, or galera, but also put Madre Magdalena in charge of it. She saw to it that women were branded with an iron that imprinted the sign of the galera upon the right sides of their backs so that the permanent image would be, in effect, not only a badge of shame to them but also a warning regarding her galera, a place other women should wish to avoid.[12]

1 Rebellion and BDSM

Some gay men submit to branding to proclaim their alienation from normal society and heterosexuality. Their brands reflect their rebellious refusal to “assimilate” to the “mainstream.” The marks in their flesh declare to the world their bearers’ “difference,” independence, and autonomy.[13] For various reasons usually associated with BDSM, members of heterosexual couples also sometimes brand themselves or one another, with the results being ruled legal or illegal, if they come to trial, on a “case by case basis” in the United Kingdom.[14] In the United States, no federal law exists concerning human branding in the context of consensual BDSM acts, although, depending on the circumstances, New Jersey state law may consider such conduct to constitute either simple assault or disorderly conduct.[15] Top 10 Fascinating Examples Of Cultural Body Modification