Sylvester Clark Long is probably the easiest fake memoirist on this list to sympathize with. Long soared to fame after he adopted the name Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance and published his memoir, Long Lance. Long’s book detailed his life as a Blackfoot chief’s son. He claimed that he had graduated from West Point, and had served heroically in the First World War, gaining the rank of captain after having been wounded eight times. The truth, however, was that Long had been born in North Carolina to a mother of mixed Croatan and white ancestry and a father who was black, Cherokee, and white. Rather than being a chief, Long’s father had been a humble janitor. In the segregated south, Long was classified as black and had little chance of advancement. As a child he claimed to be half Cherokee and attended an Indian Residential School in Pennsylvania, where he excelled. After graduating from a military academy in 1915, he joined the Canadian Forces and fought in the Great War. Following the war, he settled in Alberta, claiming that he was an American Cherokee and a war hero. He landed a job with the Calgary Herald, which he held for three years before being fired and moving on to a successful career in freelance writing. While in Alberta, Long took the opportunity to absorb all of the information he could on the culture and issues facing the First Nations. Long was heavily critical of the Canadian government for their unjust policies toward the natives, leading to his adoption by the Kainai Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy. After publishing his highly successful memoir, Long became a darling of New York’s high society and used his fame to give expensive speeches, promote a shoe for the B.F. Goodrich Company, and even star in a 1929 Silent Film. When it emerged that Long was not a full-blooded Blackfoot and that he, in fact, had black ancestry, he was quickly abandoned by his former admirers. One of these former admirers, author Irvin Cobb, reportedly exclaimed, “We’re so ashamed! We entertained a nigger!” Although Long did use his fame for personal gain, he also used it to bring attention of the many injustices facing First Nations in both the United States and Canada. Following his exposure and plummet from celebrity, Long grew depressed and committed suicide in 1932. His will bequeathed his remaining assets to a Residential School in Southern Alberta.

Papillon is a memoir written by convicted felon, Henri Charrière, in which he related the tale of his adventures in various prisons and penal colonies throughout French Guiana and its environs. The book was a runaway bestseller when it was released in France in 1969, was translated into over 15 languages, and was made into a 1973 movie starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman. When Charrière shopped the book, it was intended as a novel, but he was convinced to sell it as a personal memoir by his publisher, Robert Laffont. Nevertheless, Charrière insisted to the public that the entire book was true for the rest of his life. In a narrative brimming with self-importance, Charrière maintained that he was wrongfully convicted of killing a friend, sentenced to hard labour, and that he had a series of escapes and recaptures before being sent to the Devil’s Island Penal Colony. On Devil’s Island, the butterfly-tattooed convict maintained the he made yet another daring escape on a raft made of coconuts. After this escape, he claimed he had been sent to a Venezuelan detention camp before being pardoned and becoming a Venezuelan citizen. Among his claims, were the assertions that he had stabbed a snitch in prison, lived among natives where he had married and impregnated two teenage sisters, and that, after being recaptured, he had convinced a judge to reduce his sentence because they hadn’t hit the prison guards that hard when they had escaped. So what was true? Henri Charrière had been convicted of killing a friend, he had escaped from the French Penal Colony in French Guiana, he had been sent to solitary on the island of St. Joseph, and he had eventually escaped to Venezuela after being transferred back to the mainland. The rest of the story was embellished with the accounts of other prisoners and with fantasy from Charrière’s fertile imagination. There is no reason to believe that Charrière was innocent, his first escape was closer to a year than a week after his imprisonment, and many of the excessive rules and conditions Charrière described had been abolished before his arrival. Furthermore, it is unlikely that Charrière had ever even been on Devil’s Island as it was reserved for those convicted for treason, and, even if he had been on Devil’s Island, this French MacGyver never escaped on a coconut raft. Fellow inmates and prison records attested to the fact that, contrary to his portrayal of himself, Charrière was a rather quiet and submissive prisoner who caused few problems. Already in 1970, the claims of Papillon were overturned by Gérard de Villiers in Papillon Egpinglé (Butterfly Pinned). Charrière vehemently denied de Villiers’ claims, even trying to have his book banned. Still, if internet articles are any indication, there are those who continue to believe the events described in Papillon are gospel.

When this book hit the market in 1971, it caused quite a stir. Here was the diary of a troubled teen who had been drawn into the drug culture, had engaged in sexual promiscuity, and who had eventually died of a drug overdose. Finally, the world had a view into the troubling world that teens inhabited, full of drugs, sex, peer pressure and depression. And what a cautionary tale for those teens that ever decided to wear hippie clothes or use marijuana! The book was promoted as nonfiction, and its cover not only declared it to be written by “Anonymous,” but also proclaimed to contain “the actual story of a desperate girl on drugs and on the run who almost made it.” The book’s editor, a Mormon youth counselor named Beatrice Sparks started to appear in the media soon after the book was published. Finally, in 1979, Sparks admitted that she had changed the original diary of a young girl and that she had embellished the account based on her experiences with counseling troubled teenagers. The real protagonist, she insisted, had not died of a drug overdose, but may have committed suicide. Rather inconveniently, she had destroyed much of the original diary after transcribing it while the rest of it was locked away in the publisher’s vault. No relative of the book’s protagonist, if indeed such a person exists, has ever come forward to verify any part of the book. Sparks holds the sole copyright over the book and, rather than being listed as editor, she is listed as the book’s author at the U.S. Copyright Office. Sparks has made various claims to hold a PhD, but this has never been substantiated. She has published a number of other books that also claim to be the diaries of troubled teens but are, in reality, veiled morality tales. The most notable of these, “Jay’s Journal” is based on the journal of a young man who committed suicide. Jay’s parents were appalled when Sparks added bizarre and clearly fictional accounts of Satanism to Jay’s diary entries. Sparks denied that she had made these accounts up, claiming that she had based them on letters and interviews with Jay’s friends. Although Go Ask Alice is now classified as fiction, Sparks’ numerous other titles are trumpeted as non-fiction. Go Ask Alice is commonly on summer reading lists, and has been banned by many school boards, not because the author is a complete fraud, but because of its depictions of sex and drugs.

Asa Carter and Forrest Carter, it appears, could not have been more different. Asa Carter was a virulent racist, a man who had lost his broadcasting job in 1954 over his anti-Semitic comments. Asa founded and wrote for the polemical and racist magazine, The Southerner. In the era of segregation, Asa was a strong defender of the status quo, even taking charge of a Birmingham chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. An assault on Nat King Cole, the beating of a civil rights leader, the stabbing of the leader’s wife and the brutal castration of a black man all occurred under his leadership. Recruited indirectly by George Wallace, the Democrat, Asa even wrote the governor’s famous pro-Segregation speech: “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Forrest Carter, in direct contrast, was a gentle soul, a mustachioed Stetson-wearing cowboy with a soft folksy drawl. He was the storyteller in Council to the Cherokee Nation, a descendant of the Cherokee himself who told the story of his orphaning at a young age, and his noble upbringing by his Cherokee grandparents in his memoir, the Education of Little Tree. But, although Forrest vehemently denied the connection to his racist past, Asa and Forrest Carter were the very same man. Asa Carter had no native ancestry, and members of the Cherokee nation have heavily criticized the inaccurate portrayal of their words and customs. The book has sold more than a million copies, before the rights were snapped up in 1985 by New Mexico Press, which has continued strong sales to this day. All of this, despite the book having been exposed as fraudulent almost immediately upon its publication. The book no longer contains the true story subtitle, nor does it mention Carter’s supposed role as a Cherokee “Storyteller in Council.” Since yet another expose of the book’s lies was published in 1991, New Mexico Press has reclassified the book as fiction, although there is no mention of the author’s dark past. It is difficult to divine Carter’s motivation for the book. Some have hypothesized that he wanted to atone for his racist past, others argue that beneath the tale of the noble savage is a veiled anti-governmental polemic, while others say it is just the hypocrisy of a an unreformed white supremacist. In 1994, Oprah Winfrey promoted the “very spiritual” book on her television show. Finally, in 2007, Oprah pulled the book from her list of recommendations, after learning the truth about Asa Carter.

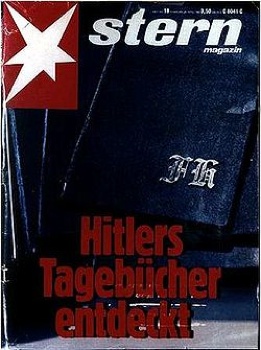

Imagine, Adolf Hitler wrote over sixty volumes of a secret diary that was finally uncovered 34 years after his death. This would be an incredible find: personal handwritten entries that would provide insight into the mind of one of the twentieth century’s greatest villains. The German journalist for Stern Magazine who uncovered the story was enthralled by the possibility, and it all seemed plausible. The diary was supposedly recovered from the wreck of a plane that had been carrying Hitler’s personal belongings southwards. The journalist, Gerd Heidemann, verified the crash and also found that Hitler, upon learning of the crash, had angrily exclaimed, “In that plane were all my private archives that I had intended as a testament to posterity. It is a catastrophe!” Furthermore, it was claimed that the diaries had been in the hands of an East German general, having been found by him in a barn. It was believable that the diary had remained hidden for so long behind the Iron Curtain. Through intermediaries, Heidemann had contacted the supplier of the diaries and, with the backing of his magazine, had paid over 9.9 million marks for all sixty-two volumes. Stern Magazine had handwriting experts examine and compare the script from three pages of the diaries with Hitler’s handwriting. The experts concluded that they matched, and the jubilant magazine broke the story on April 25th, 1983. Other magazines, including Parismatch, Newsweek, and the the London Times, enthusiastically endorsed the story. Skeptics expressed their doubts, as none of Hitler’s inner circle had ever seen him keep a diary and Hitler was known to dislike writing. The Federal Archives of West Germany examined the notebooks, and found that the paper, ink, and glue in the diaries were all too recent to have been used by Hitler. All sixty two volumes of Hitler’s supposed diaries had been expensive forgeries, the work of Konrad Kujua, a forger specializing in duping collectors of Nazi memorabilia. Kujua claimed that Heidemann had known that the diaries were fake, but Heidemann claimed that he had been oblivious. Both Heidemann and Kujua were convicted of forgery and embezzlement, serving 42 months each.

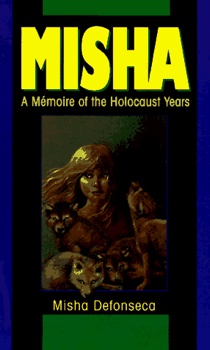

It was an incredible tale: a young Jewish girl’s parents are deported, she is adopted by an abusive Catholic family who changes her name to Monique de Wael, so she wanders across Europe searching for her parents, is adopted by a pack of wolves, eats offal and worms, and even kills a German officer with her pocketknife. The girl, Misha de Fonesca, has walked a total of over 3,000 kilometres from Belgium to Ukraine and back, sneaking in and out of the Warsaw ghetto, undetected, along the way. The story is unbelievable, it’s triumphant, it’s inspiring, and it’s entirely false. The author is actually named Monique de Wael and is a Belgian, whose Catholic parents were resistance fighters and were taken away by the Nazis when Monique was four. She was raised by a grandfather, and later an uncle, whose family may or may not have mistreated her. She moved to the Massachusetts with her husband in 1988, where she began to tell the local synagogue her incredible tale of her survival as Jewish girl searching for her parents. The story was picked up by a publisher and published to minimal success in the United States before being translated into 18 languages and becoming a European bestseller. The story was questioned from the beginning, but was definitively debunked by two genealogists who tracked down de Wael’s birth certificate and a school registry that showed de Wael at school when she was supposedly wandering about Europe. De Wael acknowledge the fraud in 2008, but qualified her apology by saying “it’s not the true reality, but it is my reality. There are times when I find it difficult to differentiate between reality and my inner world.”

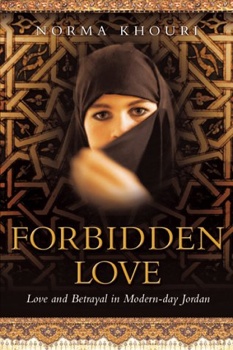

In her acclaimed memoir, Forbidden Love, Norma Khouri tells the story of the honor killing of her best friend, Dalia, in Damman, Jordan, during the early nineties. Khouri told of working in the same salon in as her friend, where Dalia met and fell in love with a British army officer named Michael. Michael is a Roman Catholic, so Dalia cannot let her traditional Muslim family know of her romantic interest in him. Khouri acted as a go-between and helped Dalia keep the romance a secret. When the romance did come to light, Dalia’s enraged father stabbed her multiple times. Khouri, afraid for her life, was smuggled out of Jordan with the help of the dashing young Michael. Sold in over 15 countries, the memoir sold over 200,000 copies in Australia and enthusiastic Australians voted it among their favorite 100 books of all time. The entire story, however, had emerged from Khouri’s imagination. Her real name was, in fact, Norma Majid Khouri Michael Al-Bagain Toliopoulos, and she had spent most of her life in suburban Chicago. She had moved to the United States from Jordan with her family at the age of three, and studied Computer Science after graduating from Catholic High School. She met a Greek-American man, whom she had two children with before marrying in 1993. Records confirm that Norma was in Chicago for the entire timeline of the events that she related in her memoir. In 2000, Norma submitted her manuscript to a literary agent, who sold it to 16 international publishers. Norma Toliopoulos then moved with her family to Australia, and her memoir went on to wild success. The book raised eyebrows in Jordan, and was researched by the Jordanian National Commission for Women who found over 70 exaggerations and serious errors. They submitted their report to Random House Australia, who responded that they were satisfied with the veracity of the story, and that only names and places had been changed to protect the identities of those involved. When confronted with the increasing evidence of the lies contained in her book, Norma would deftly elaborate on her original story or blatantly lie – even flatly denying ever having been to the United States prior to 2003. When the scandal was broken by Australian journalist, Malcolm Knox, Random House pulled the book from the shelf. Norma Toliopoulos, however, stuck to her story and boldly agreed to a documentary that followed her to Jordan. With the camera on her, she did her utmost to try to prove the truth of her memoir. Her story unravels rather quickly, but Norma is a deft liar and is able to make a lot of her obfuscations and excuses sound almost plausible.

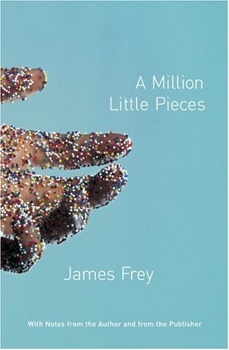

James Frey wants us to believe that he is a tough but sensitive bad-boy writer with a drug problem. The truth is, he’s a sensitive but boyish bad writer with a truth problem. The memoir purports to tell the true story of his drug and alcohol problems, his rehab, prison stints, and his personal triumph over his addictions. The book was released in 2003 to mixed reviews before being picked up as a selection for Oprah’s Book Club. The book soared to the top of the bestsellers list, with a public entranced with Frey’s incredible account of his personal conquest of his addictions. The Smoking Gun, a website that routinely publishes mug shots and legal documents, after having much difficulty finding a booking photo for Frey, began a deeper investigation into the claims he made in his memoir. Months later, the Smoking Gun published their results, exposing a litany of lies and embellishments by Frey relating to his claims of criminal activity. After being exposed, Frey issued a half-hearted author’s note that admitted that large portions of the book had been fabricated: that he had never been involved in the train accident that killed a schoolmate (although he knew her), that he served a few hours in prison rather than three months, and that he had embellished his account of his arrests. Although his claim that a root canal procedure had been done without anesthesia is clearly false, Frey claims that he wrote it from memory and that he has records that “seem to support it.” Conveniently, he also claims that other patients at the treatment facility had their names and identifying characteristics changed to protect their anonymity. Frey, ever the conscientious writer, cannot reveal their identities. His apology comes off as flat and forced, especially with these lines: “This memoir is a combination of facts about my life and certain embellishments. It is a subjective truth, altered by the mind of a recovering drug addict and alcoholic.” Manipulating the truth has nothing to do with your point of view and everything to do with being a pathological liar. Some have tried to defend Frey by referring to his triumph over addiction as the important message and claiming that “minor” lies shouldn’t matter.

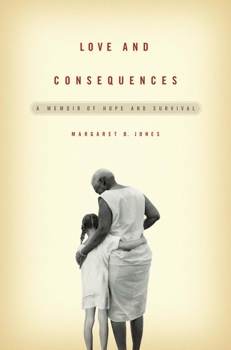

If there were a literary version of blackface, this would be it. Author Margaret B. Jones wrote this memoir based on her life as a gang member in south-central L.A.. Claiming to look dark “like a Mexican” and to be half-native and half-white, Jones writes the entire memoir laced in her own unique version of ebonics. The book’s jacket clearly depicts a white woman, but it seems the publisher never questioned this minor inconsistency. Jones claimed to have been taken from her parents at the age of six and placed in a black foster home in L.A.’s toughest neighborhood because this is, after all, social services’ standard practice for all half-white half-native foster children. She wrote of her membership in the Bloods and her life’s struggles, with all of the knowledge and experience of an outsider who owns several rap albums and has watched Boyz In the Hood at least twice. She even makes the incredibly ludicrous claim that the first white baby she ever saw was her own child (conceived with the first white man she had ever slept with). The memoir received critical praise, with the New York Times, Entertainment Weekly, and O Magazine loudly endorsing it. The book was poised to sell millions, when Jones was recognized, by her sister, as one Margaret “Peggy” Seltzer. Seltzer, it turns out, is an entirely Caucasian suburbanite whose affectation of ebonics is made all the more clownish by her private school education. Seltzer had managed to sell the story to the publisher by parading a series of people posing as her foster siblings, using the published accounts of her experiences from the book of an author she had duped, and presenting other fake evidence consisting of photos and letters. Seltzer defended her book by saying she was giving “a voice to people who people don’t listen to.” Margaret Seltzer, the voice of the ghetto.

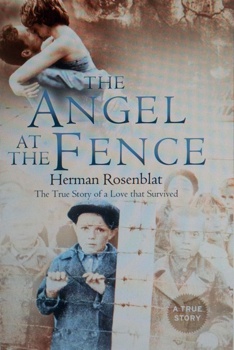

Full title: “Angel At the Fence: The True Story of a Love that Survived”. Herman Rosenblat, a Holocaust Survivor, wrote his memoir recounting his time at Schlieben camp, Buchenwald. In his book, Rosenblat claimed that a girl had passed him food through the fence of the concentration camp. One day in 1945 he had told her that he would not be able to take her apple the next day because he was scheduled to be gassed to death. Against all odds, he survived and this same girl was the one he met on a blind date in 1957 and who later became his wife. Wow, Oprah enthused, this “is the single greatest love story, in 22 years of doing this show, we’ve ever told on air.” The problem? The entire central premise of the book was a complete fabrication. As Deborah Lipstadt, a Holocaust scholar and activist against anti-Semitism pointed out, Buchenwald had no gas chambers and, even if it did, there is no way the author would have had his impending gassing announced to him. She further argued for the importance of pursuing historical truth, especially in the face of Holocaust deniers, who love exploiting inconsistencies. Furthermore, researchers found that Rosenblat’s wife was, in fact, hidden over three hundred kilometers away during the war. Not only that, but there would have been absolutely no way for a civilian to approach the fence and pass food to a prisoner, as the only accessible point was immediately beside the SS Barracks. Rosenblat initially defended his memoir before admitting that it had been embellished and that he had never met his wife at Schlieben. The book’s publisher, Berkley Books, withdrew it from publication, but not before the film rights were bought by Atlantic Overseas Pictures for $25 million. The movie, which was set to star Richard Dreyfuss, appears to have been cancelled. Still, its producer, Harry Saloman, defended it by claiming that Rosenblat’s story has been censored by an overzealous publishing industry and that “Rosenblat’s story of survival, and its message of love and hope will not be silenced.”