This lister hopes some of the victims’ families and friends frequent Listverse and enjoy this list. Either way, we all suffer to think of a Christmas suddenly without our children. Classical music, perhaps more than any other genre, possesses a quality of timelessness. Its best examples do not remind us of any century or era, but provide what the French call an “oubliette,” “a place of forgetting.”

Let us start with one of the finest fugues from the all-time master of contrapuntal music. This was chosen only because it is in a major key, so there’s no sorrowful, doleful atmosphere, and because among major-key fugues over the centuries, this one does not shy away from declaring and exploring its theme in a surprisingly difficult key for keyboard instruments. You may liken this one to the Pearly Gates opening and all the greens and blues of Paradise spreading into the distance.

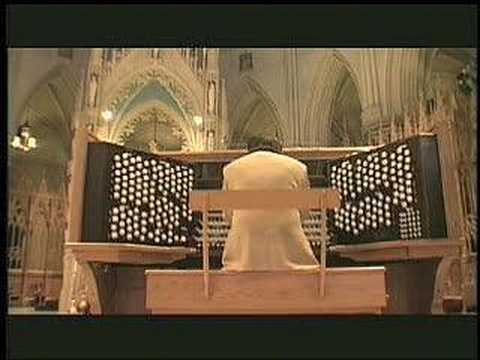

This is Widor’s most famous piece, and for good reason. He wrote 10 symphonies for the organ at a time when Bach’s 1800s resurgence had claimed the title of Organ Gods firmly for Germany. The French wanted a share of the glory, and while championing the works of Couperin, Marchand, and a host of others, the contemporary greats like Franck, Widor, Eugene Gigout, Louis Vierne, and Marcel Dupre, to name a few, published tons of organ works in as many genres as they could think of. Widor’s fifth symphony for solo organ has 5 movements, none of them a fugue, but instead they are written in legitimate sonata-allegro form, except for the last movement. Toccata is Italian for “touch,” and the traditional form is meant to sound light and delicate, typically allegro to presto. The most famous example is Bach’s in D minor, BWV 565. Widor’s is second, with a repeated rhythm phrased throughout that is quite easy to play even for intermediate students. Everything lies well under the fingers. As a nod to The Hobbit, and New Zealand (Heaven) in general, this piece is possibly the most quintessential high-fantasy, sword-and sorcery genre music in the Classical canon. It sounds like the undertaking of the Fellowship to journey across Middle-earth to destroy the One Ring, or like Bilbo and the Dwarves setting off for the Lonely Mountain. A publisher nicknamed this one the “Rhenish,” from the German “Rhein” for the Rhine River, as it sounded to him like the Bavarian Rhine valley. The main theme is epic, opening on full-orchestral half notes, with an immediate restatement by the brass section. It has been called “heroic” many times, because of Schumann’s heavy use of French horns. Music Appreciation 101: French horns signal the hero. James Horner ripped it off for his “Willow” score. But then, almost all film composers rip off Wagner, even if they don’t want to. Tchaikovsky’s last three symphonies – 4, 5, and 6 – are his masterpieces; and few, if any, symphonies flaunt more sweeping exhilaration than his fifth. The final movement is about 15 minutes long and recycles the two main themes of the 1st movement into new development. Tchaikovsky described the finale as “pure optimism,” and given the way his life turned out, his later criticism of it is understandable: “insincere, perhaps criminally so, like a fairy tale for an audience beyond adolescence.” We can forgive him for that ever since WWII, when the fairy tale came true. Not that there was any doubt from 1943 on that the Allies would win, but to slack off from the attack, secure in this confidence, is the fastest way to lose a war. So when the good guys took the victory, the unparalleled blood and gore made this finale’s “stormy Cossack onslaught” more realistic. WWII gave this symphony lasting popularity. This is one of this lister’s personal favorites. Respighi’s “Pines of Rome” is among the best works of program music in history, worthy of recognition alongside Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique and Beethoven’s 6th Symphony. There are four movements, and Respighi intended each to depict an ancient Italian scene, the last one a rather simple image of an army returning along the Appian Way to a triumph in Rome. It has always seemed most fitting on the surface to think of Julius Caesar’s 13th Legion, the most famous of Rome’s armies, but it returned from Gaul in the north to Rome, and the Appian Way begins at Rome, which it connects to Southeast Italy. Respighi scored this movement for full orchestra, plus 8, 16, and 32-foot organ pedal stops on the lowest B-flat. These pedal beats give the music its driving pulse and Respighi specifically reminds performances, in the score, that the organ is as indispensable as the heart. The music sounds precisely as he intended, as a grand entrance: Caesar at the head of the 13th, Jesus riding a donkey into Jerusalem, and so on.

The first of three Mahler entries, but flooding the list with one composer was not arbitrary. Mahler wrote symphonies almost exclusively, and although he was certainly obsessed with death, his music is rarely morbid. Most of his symphonies have happy endings. He seems to have been fascinated with the notion of no longer existing. He intended his second symphony to be a sort of grand funeral for the hero of his first.

The second begins darkly, and becomes darker, but turns into an apotheosis of death, since it leads to new life. The lyrics beginning the finale of the last movement are Mahler’s, added to a poem by Friedrich Klopstock. Mahler’s addition – translated from German – reads: “Oh, believe, you were not born for nothing! You have not lived, or suffered, for nothing! What was created must perish, and what perished must rise again! Stop trembling! Prepare yourself to live!”

Mahler sets this to music so glorious that at the premiere, women passed out in the aisles and grown men wept.

Though this symphony certainly has its tragic moments, it is possibly Mahler’s least morbid. It is also the longest in the standard repertoire, with some performances lasting over an hour and a half. Mahler intended it as program music, and titled the movements to tell a narrative. The final movement he titled “What Love Tells Me,” and it lasts some 30 minutes. It is notoriously difficult for an orchestra to play properly slow throughout. The tendency is to rush, and an iron-willed conductor is required.

It builds and builds to a climax, then backs off and builds to another which is even more powerful, then backs off and builds to an impossibly ultimate elation. If you will pardon the expression, this movement is passionate musical intercourse, a consummation of love, and not just of the physical, which is love’s basest form, but of all aspects and levels of what love means to Mahler, and what he makes it tell us.

There follows the climax a prolonged afterglow that seems to make sure of love’s thorough fulfillment, before dwindling into a vibrant quiet on the tonic, without a bang to let the audience know it’s over.

No 1812 Overture?! No – as a matter of fact, this one is even more exciting, and it doesn’t need to cheat with siege cannons. Tchaikovsky could build a piece of music more inexorably than perhaps any other composer. This is not to say the music is better, but in terms of pure exhilaration he can put you on the edge of your seat more readily that just about anyone.

The last movement of his fourth symphony is one long climax. It begins in a breakneck fortissimo, and ends in an even faster breakneck fortissimo, based on a Russian folk song, “In the Field Stood a Birch Tree.” The 1812 Overture also makes excellent use of such folk songs to express the Russian countryside.

This finale is splendidly punctuated with pounding tympani, quite in the vein of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which is surprising given that Tchaikovsky was very critical of Beethoven. Tchaikovsky loved melody more than anything and referred to Mozart as “the Christ of music.” This movement is thus loaded with development of the primary theme, slamming through two climaxes before returning to another statement of it for good measure, then slamming it into an ebullient roar of happiness.

Beethoven set out with this mass to write his finest sacred work – in the same way that he set out to write his finest symphony with his ninth, his finest sonatas with his last five, and his finest chamber music with his late quartets. By the time he wrote these pieces, he was completely deaf, unable to hear a cannonball explode next to him.

“Solemn Mass” is just another title for the standard Latin mass, distinguished from the “Missa brevis,” or “Brief Mass.” The Solemn Mass usually consists of 5 movements, the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei. Bach’s Mass in B minor may be considered a solemn mass, but is also one of the few “Missa tota” (“Total mass”), to have been composed, omitting none of the minor lyrics.

Beethoven intended his Gloria to be the most glorious music he could possibly compose. His religion is hotly debated, but there can be no doubt that he believed in God, as he wrote in the margin of the Gloria manuscript, “Gott über alle Dinge!” “God over all things!”

Thus, this setting of praise to God is the most primordial in its expression of love and exuberance, with wanton abandon, a sort of Bacchanalia without sin, and with only worship of God for intoxication. It includes one of Beethoven’s best and grandest fugues, on “In gloria Dei patris. Amen,” which translates to “in the glory of God the Father. Amen.” This leads without pause into a searing coda of full orchestra, and a chorus with soloists, trading back and forth, until the orchestra storms from the Tonic D Major into the dominant G and sweeps the chorus to an ethereal “Gloria!” ending on the 5 chord.

There exists in all music no more cosmic, resplendent conclusion to an exposition and exploration of any subject than the last 15 minutes or so of this symphony. The actual finale, if you want to call it that, may be defined as the final six minutes, beginning with the Chorus Mysticus singing, “Everything transitory is only an approximation; what could not be achieved comes to pass here; what no one could describe is here accomplished; the Eternal Feminine draws us on high.”

This begins “as a breath” in Mahler’s notes, then builds into an exultation of love, eternal life, and death conquered. It transcends the word “finale.” It cannot be described in a single word. Many have been tried: “celestial,” “euphoric,” “jubilant,” “overpoweringly ecstatic,” to name a few. Perhaps “empyrean” is the best. The orchestration calls for massive forces, including an organ and an off-stage brass band of 4 or 5 trumpets and 3 trombones. It’s hard to say what images come to our different minds, but Mahler doesn’t leave much room. It sounds like paradise.