Had Fossett not been found he would certainly have made this list. It is hard to believe that something as big as an airplane can simply vanish, leaving behind no traces of where it went down. Yet, even over land, airplanes go missing and are never discovered. Or only discovered decades later. Here are ten tales of people who took off in airplanes and vanished, never to be seen again.

Charles Eugène Jules Marie Nungesser was a French ace pilot and adventurer, best remembered as a rival of Charles Lindbergh. Nungesser was a renowned ace in France, rating third highest in the country for air combat victories during World War I. After the war, he came to the United States where he flew airplanes in such movies as Dawn Patrol. It was during the time he flew airplanes for movies that he got the idea to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. Eventually Nungesser made good on his idea and set off on an attempt to make the first non-stop transatlantic flight, from Paris to New York. He was flying with wartime comrade François Coli, in their plane The White Bird (L’Oiseau Blanc), a Levasseur PL.8 biplane. Coli was already known for making historic flights across the Mediterranean, and had been planning a transatlantic flight since 1923, with his wartime comrade Paul Tarascon, another World War I ace. When Tarascon had to drop out because of an injury from a crash, Nungesser came in as a replacement. Nungesser and Coli took off from Paris on May 8, 1927. Their plane was sighted once more over Ireland, and then was never seen again. The disappearance of Nungesser is considered one of the great mysteries in the history of aviation, and modern speculation is that the aircraft was either lost over the Atlantic or crashed in Newfoundland or Maine. Two weeks after Nungesser and Coli’s attempt, Charles Lindbergh successfully made the journey, flying solo from New York to Paris in Spirit of St. Louis.

Sigizmund Levanevsky was born to a Polish family, in St. Petersburg, Russia. He took part in the October Revolution on the Bolshevik side, and later took part in the civil war in Russia, serving in the Red Army. In 1925, he graduated from the Sevastopol Naval Aviation School and became a military pilot. As a pilot he accomplished several long distance flights. One of them took place on July 13, 1933, when Levanevsky rescued the American pilot James Mattern, who had been forced to land near Anadyr during his attempt at a flight around the world. In April 1934, Levanevsky took off from an improvised airfield on the Arctic ice of the Chukchi Sea, taking part in the successful aerial rescue operation saving people from the sunken steamship Cheliuskin. He was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union for this deed. In August 1935, Levenevsky completed his first flight over the North Pole, a journey from Moscow to San Francisco. A contemporary of Charles Lindbergh, Levanevsky was celebrated as a hero of the new age of aviation. In early 1936, he flew back from Los Angeles, USA to Moscow, USSR. On August 12, 1937, a type Bolkhovitinov DB-A aircraft with 6-man crew, under captaincy of Levanevsky, started its long distance flight from Moscow to the USA, via the North Pole. The radio communications with the crew broke off the next day, on the 13th of August, when the aircraft encountered adverse weather conditions. After the unsuccessful search attempts, all the members of the crew were presumed dead. In March 1999, Dennis Thurston of the Minerals Management Service in Anchorage, located what appeared to be wreckage in the shallows of Camden Bay, between Prudhoe Bay and Kaktovik. There was conjecture in the media that it was Levanevsky’s aircraft, but a subsequent attempt to locate the object again proved unsuccessful.

Sir Charles Edward Kingsford Smith was a well-known early Australian aviator. In 1928, he made the first trans-Pacific flight, from the United States to Australia. He almost didn’t live to set world records in aviation. As a boy, living in Australia, young Charlie Smith was rescued from certain drowning at Sydney’s famous Bondi Beach, by bathers who, just seven weeks later, were responsible for founding the world’s first official surf life saving group, at Bondi Beach. During WWI he served in Gallipoli and eventually earned his wings. He was shot down and had part of his foot amputated as a result. Yet he continued to fly in the US as a barnstormer, and then back in Australia as a pilot and aviator. On May 31, 1928, Kingsford Smith and his crew left Oakland, California, to make the first trans-Pacific flight to Australia. The flight was in three stages. The first (from Oakland to Hawaii) was 2,400 miles, took 27 hours 25 minutes and was uneventful. They then flew to Suva, Fiji, 3,100 miles away, taking 34 hours 30 minutes. This was the toughest part of the journey as they flew through a massive lightning storm near the equator. They then flew on to Brisbane in 20 hours, where they landed on June 9, 1928, after approximately 7,400 miles total flight. On arrival, Kingsford Smith was met by a huge crowd of 25,000 at Eagle Farm Airport, and was feted as a hero. He also made the first non-stop crossing of the Australian mainland, the first flights between Australia and New Zealand, and the first eastward Pacific crossing from Australia to the United States. He also made a flight from Australia to London, and set a new record of 10.5 days. Kingsford Smith and co-pilot Tommy Pethybridge were flying the Lady Southern Cross overnight from Allahabad, India, to Singapore, as part of their attempt to break the England-Australia speed record held by C. W. A. Scott and Tom Campbell Black, when they disappeared over the Andaman Sea, in the early hours of November 8, 1935. Eighteen months later, Burmese fishermen found an undercarriage leg and wheel which had been washed ashore at Aye Island in the Gulf of Martaban, off the southeast coastline of Burma. Lockheed confirmed the undercarriage leg to be from the Lady Southern Cross. The undercarriage leg is now on public display at the Powerhouse Museum, in Sydney, Australia. In 2009, a Sydney film crew claimed they were certain they had found the Lady Southern Cross where the landing gear had been found in 1937, at Aye Island.

Sir Ian Mackintosh was a British novelist and writer who is best remembered for creating the television series The Sandbaggers and Warship. On July 7, 1979, Mackintosh, along with Susan Insole, the daughter of an English cricket player, and the pilot, departed Anchorage, Alaska, on route to Kodiak. Their plane developed engine problems and was believed to have ditched in the ocean about 45 miles from the Kodiak shore. Two US Coast Guard rescue helicopters and a Coast Guard cutter were immediately dispatched to the area where the plane ditched. No sign of the plane was ever found. The search continued for three days. Sir Ian Mackintosh was rumored to have been a British spy, and some believe his disappearance was somehow related to his clandestine work, but there is no proof of this. In all likelihood, the plane ditched and either sank, taking all three to the bottom, or the three survived and then drowned or succumbed to the cold.

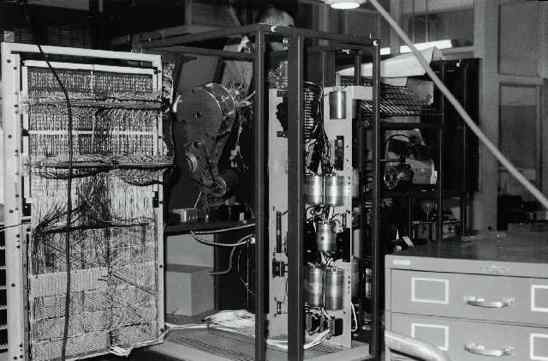

George Cogar was a pioneer in the field of computers. A member of the UNIVAC 1004 electronic design team, Cogar would eventually invent the data recorder, which did away with the need for computer punch cards. His company later invented an early type of personal computer. On September 2, 1983, George Cogar, five others and the pilot were on board a plane headed from Vancouver Island to a hunting lodge in Smithers, Canada. The plane disappeared, presumably over British Columbia, Canada. A one-week search effort covered nearly 40,000 square miles, but no trace of the plane or its occupants was ever found. At the time, it was the largest coordinated search in Canadian history and cost nearly $1 million. The families of the lost men, all millionaires, decided to continue the search on their own. So far, no trace has been found.

Sir Arthur Coningham was an RAF Air Marshal who served Britain in WWII, as Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief Flying Training Command. Coningham is chiefly remembered as the person most responsible for the development of forward air control parties directing close air support, which he developed as commander of the Western Desert Air Force between 1941 and 1943, and as commander of the tactical air forces in the Normandy campaign, in 1944. In the film Patton, Coningham is played by actor John Barrie. During his scene, in which General George S Patton is complaining about the lack of air cover for American troops, Sir Arthur confirms to Patton that he will see no more German planes. As he has completed his sentence, German planes strafe the compound. Coningham had recently retired from the RAF when the plane he was in disappeared over the western Atlantic. He was one of 25 passengers aboard an Avro Tudor IV G-AHNP Star Tiger together with 6 crew, who were lost when their flight from Santa Maria Airport, in the Azores, failed to reach its destination of Kindley Field, Bermuda. The plane was attempting to locate Bermuda airspace when the Radio Officer, Robert Tuck aboard Star Tiger, requested a radio bearing from Bermuda, but the signal was not strong enough to obtain an accurate reading. Tuck repeated the request eleven minutes later, and this time the Bermuda radio operator was able to obtain a bearing of 72 degrees, accurate to within 2 degrees. The Bermuda operator transmitted this information, and Tuck acknowledged receipt. This was the last communication with the aircraft. The Bermuda radio operator tried several times to contact the Star Tiger again, without success. He then declared a state of emergency. He had heard no distress message, and neither had anyone else, even though many receiving stations were listening on Star Tiger’s frequency. The USAAF personnel operating the airfield immediately organized a rescue effort that lasted for 5 days. Twenty-six aircraft flew 882 hours in total, and surface craft also conducted a search, but no signs of Star Tiger or her 29 passengers and crew were ever found. The disappearance of the Star Tiger baffled the official British investigation, which could offer no explanations for why the plane had disappeared. The disappearance of the Star Tiger is one of the founding mysteries that led to the development of the concept of the Bermuda Triangle.

Andrew Whitfield was the nephew of wealthy steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. Whitfield was a graduate of Princeton University and had been employed as a business executive. An amateur pilot, Whitfield owned a small red and silver Taylor club monoplane which he occasionally flew (mostly for recreation). At the time of his disappearance, he had accumulated 200 hours of flying experience. He departed from Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York, on the morning of April 17, 1938, in his Taylor Cub monoplane. He had planned to land at an airfield in Brentwood, New York (approximately 22 miles away). He was only supposed to be in the air for fifteen minutes, but he never arrived as scheduled. One source reported that Whitfield’s plane had been flying steadily—but then Whitfield “nosed his plane into a mild easterly wind, [and] disappeared from sight.” His plane had enough fuel for a 150-mile flight. Neither Whitfield nor his plane has ever been recovered. After his disappearance an investigation discovered that (on the same day he vanished) he had checked into a hotel in Garden City, on Long Island, under an alias he occasionally employed: “Albert C. White.” Hotel records indicated that Whitfield/White had paid $4 in advance for the room and never checked out. When the hotel room was searched, it was discovered that his personal belongings (including his passport), clothing, cuff links engraved with his initials, two life insurance policies (in his name listing his wife, Elizabeth Halsey Whitfield, as the beneficiary), and several stock and bond certificates made out in Andrew’s and Elizabeth’s names, were all left behind in the hotel room. Phone records also indicated that he had called his home, while his family was out looking for him, and a telephone operator reported that she heard him say over the phone, “Well, I am going to carry out my plan.” After this information was uncovered, police theorized that Whitfield had committed suicide by deliberately flying his plane into the Atlantic Ocean–although no evidence to verify this theory has been found. A thorough search of the ocean surrounding Long Island was conducted; it turned up no signs of plane wreckage. At the time of Whitfield’s disappearance, there was no evidence that he was having personal or business problems. Whitfield had married (the former Elizabeth Halsey) earlier that year, and had been planning to move to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, (with his new wife) the same month that he disappeared.

Thomas Hale Boggs, Sr. was a member of the United States House of Representatives, for Louisiana. He was the House Majority Leader. During his tenure in Congress, Boggs was an influential player in the government. He served as Majority Whip from 1961 to 1970, and as majority leader, from January 1971 until his disappearance. As majority whip, he ushered much of President Johnson’s Great Society legislation through Congress. In April 1971, he made a speech on the floor of the House, strongly attacking FBI Director J Edgar Hoover, and the whole of the FBI. This led to a conversation on April 6, 1971, between then President Richard Nixon and the Republican Minority Leader, Gerald Ford, in which Nixon said that he could no longer take counsel from Boggs as a senior member of Congress. In the recording of this call, Nixon is heard to ask Ford to arrange for the House delegation to include an alternative to Boggs. Ford speculates that Boggs is on pills as well as alcohol. As Majority Leader, Boggs often campaigned for others. On October 16, 1972, he was aboard a twin engine Cessna 310 with Representative Nick Begich of Alaska, who was facing a possible tight race in the November 1972 general election against the Republican candidate, Don Young. Boggs and Begich disappeared during a flight from Anchorage to Juneau. The only others on board the plane were Begich’s aide, Russell Brown, and the pilot. They were heading to a campaign fundraiser for Begich. (Begich won the 1972 election posthumously with 56 percent to Young’s 44 percent, though Young would win the special election to replace Begich and won every election, up to and including 2010.) Coast Guard, Navy and Air Force planes searched for the party. On November 24, 1972, after 39 days, the search was abandoned. Neither the wreckage of the plane, nor the pilot’s and passengers’ remains were ever found. The accident prompted Congress to pass a law mandating Emergency Locator Transmitters in all U.S. civil aircraft. The events surrounding Boggs’s death have been the subject of much speculation, suspicion and numerous conspiracy theories. These theories often center on his membership on the Warren Commission. Boggs dissented from the Warren Commission’s majority, who supported the single bullet theory. Regarding the single bullet theory, Boggs commented, “I had strong doubts about it.” Some conspiracy theorists believe Boggs was killed to stop his investigation of the Kennedy assassination. In the 1970’s, it was also a bad idea to publicly take on J Edger Hoover and piss off Richard Nixon. Whether he was rubbed out, or his plane simply crashed in the Alaskan wilderness, Boggs and the plane have never been found.

First Lieutenant Felix Moncla, pilot, and Second Lieutenant Robert Wilson, radar operator, disappeared when their United States Air Force F-89 Scorpion was scrambled from Kinross Air Force Base, and subsequently went missing over Lake Superior while intercepting an unknown aircraft in Canadian airspace, close to the Canada – United States border. The USAF identified the second aircraft as Royal Canadian Air Force C-47 Dakota VC-912, crossing Northern Lake Superior from west to east at 7,000 feet, en route from Winnipeg to Sudbury, Canada. Some ufologists have associated the disappearance with alleged “flying saucer” activity and refer to it as the “Kinross Incident” On the evening of November 23, 1953, Air Defense Command Ground Intercept radar operators at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, identified an unusual target near the Soo Locks. An F-89C Scorpion jet from Kinross Air Force Base was scrambled to investigate the radar return; the Scorpion was piloted by First Lieutenant Moncla, with Second Lieutenant Robert L. Wilson acting as the Scorpion’s radar operator. Wilson had problems tracking the object on the Scorpion’s radar, so ground radar operators gave Moncla directions towards the object as he flew. Flying at some 500 miles per hour, Moncla eventually closed in on the object at about 8000 feet in altitude. Ground Control tracked the Scorpion and the unidentified object as two “blips” on the radar screen. The two blips on the radar screen grew closer and closer, until they seemed to merge as one (return). The single blip disappeared from the radar screen, then there was no return at all. Attempts were made to contact Moncla via radio, but this was unsuccessful. A search and rescue operation was quickly mounted, but found not a trace of the plane or the pilots. The official USAF Accident Investigation Report states the F-89 was sent to investigate an RCAF C-47 Skytrain which was traveling off course. No explanation for the planes disappearance was offered, but the Air Force investigators speculated that Moncla may have experienced vertigo and crashed into the lake. Others believe the plane made contact and perhaps even collided with a UFO.

Frederick Valentich was a 20-year old pilot of a Cessna 182L light aircraft who, on October 21, 1978, was on his way to King Island, in Australia, to pick up three or four friends and return to Moorabbin Airport, from which he had departed. During the 127 Nautical mile flight, Valentich advised Melbourne air traffic control he was being accompanied by an aircraft about 1,000 feet above him. He described unusual actions and features of the aircraft, reported that his engine had begun running roughly, and finally reported before disappearing from radar that “That strange aircraft is hovering on top of me again. It is hovering and it’s not an aircraft”. No trace of Valentich or his aircraft was ever found, and a Department of Transport investigation concluded that the reason for the disappearance could not be determined. The report of a UFO sighting in Australia attracted significant press attention, in part due to the number of sightings reported by the public on the night of Valentich’s disappearance. Valentich was an experienced pilot with a Class Four instrument rating and 150 hours of flight experience, and he had filed a flight plan from Moorabbin Airport, Melbourne, to King Island in Bass Strait. Visibility was good and winds were light. He departed Moorabbin at 18:19 local time, contacted the Melbourne Flight Service Unit to inform them of his presence, and reported reaching Cape Otway at 19:00. At 19:06, Valentich asked Melbourne Flight Service Officer Steve Robey for information on other aircraft at his altitude, and was told there was no known traffic at that level. Valentich said he could see a large unknown aircraft which appeared to be illuminated by four bright landing lights. He was unable to confirm its type, but said it had passed about 1,000 feet overhead and was moving at high speed. Valentich then reported that the aircraft was approaching him from the east and said the other pilot might be purposely toying with him. At 19:09 Robey asked Valentich to confirm his altitude and that he was unable to identify the aircraft. Valentich confirmed his height and began to describe the aircraft, saying that it was “long”, but that it was traveling too fast for him to describe it in more detail. Valentich stopped transmitting for about 30 seconds, during which time Robey asked for an estimate of the aircraft’s size. Valentich replied that the aircraft was “orbiting” above him and that it had a shiny metal surface and a green light on it. This was followed by 28 seconds silence before Valentich reported that the aircraft had vanished. There was a further 25-second break in communications before Valentich reported that it was now approaching from the southwest. Twenty-nine seconds later, at 19:12:09 Valentich reported that he was experiencing engine problems and was going to proceed to King Island. There was brief silence until he said “it is hovering and it’s not an aircraft”. This was followed by 17 seconds of unidentified noise, described as being “metallic, scraping sounds”, then all contact was lost. A Search and Rescue alert was given and two RAAF P-3 Orion aircraft searched over a seven-day period. No trace of the aircraft was found. The transcript of the final conversation between Valentich and the air traffic controller is very disturbing to read. As the tape of the conversation between Valentich and the air traffic control comes to an end, there are several seconds of silence, but odd metallic-like sounds can be heard in the background. Either, as some have speculated, Valentich was creating an elaborate ruse to cover up his intended self-disappearance, or he actually encountered something very strange just before he disappeared. The transcript can be found here.

No list of people who have disappeared in airplanes would be complete without a mention of the already well-known Amelia Earhart. A renowned aviator, in 1937 Earhart was attempting an around the world flight with her copilot Fred Noonan, in a Lockheed Model 10 Electra. Earhart disappeared over the central Pacific Ocean near Howland Island. Apparently lost, and possibly unable to hear radio transmissions trying to direct her to the airfield on tiny Howland Island, it is assumed Earhart and Noonan ran out of fuel and either crashed or ditched in the Pacific Ocean. Fascination with her life, career and disappearance continues to this day, with multiple theories surrounding her disappearance and possible survival of the airplane crash. Some believe she was taken prisoner by the Japanese. Others believe she and/or Noonan managed to make it to one of several tiny atolls where they later died of thirst, hunger and exposure. A recent search for her remains found what appeared to be small fragments of human bone on a tiny island. Also found were what appeared to be women’s cosmetics and other indications that perhaps Earhart had survived the airplane crash and made it to land. But the bone had decayed to such an extent that DNA analysis was unable to determine if the bone were human, let alone the bones of Earhart. Amelia Earhart remains the most well known of the people who have disappeared in airplanes.