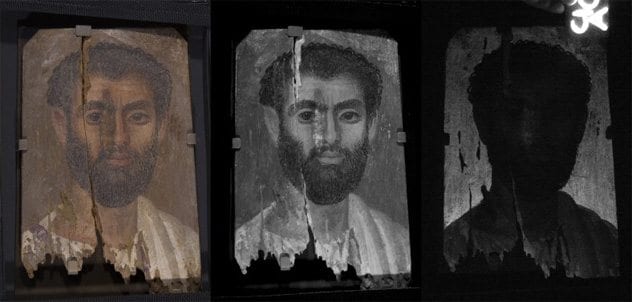

10The Tebtunis Portraits

As the first man-made pigment, Egyptian blue was sought after by ancient painters. When researchers studied 11 mummy portraits, they were stunned to find the precious tint hidden instead of flaunted. Mummy portraits were paintings of the deceased placed over the face. Found at Tebtunis, Egypt, between 1899 and 1900, the portraits reflected a popular second-century trend—using only the four colors favored by the masterful Greeks. Closer inspection of the white, black, yellow, and red revealed something surprising. The Tebtunis painters stayed true to the vogue color scheme but worked blue into the art in a way never before seen in the ancient world. Normally, Egyptian blue received a place of honor in paintings and sculptures throughout the Mediterranean, but here, it was used as underdrawings, enriching the four Greek colors with more hues and shading. Even today, researchers aren’t certain that all the ways in which Egyptian blue was used is known.

9Sacred Scandal

Today, the scandal merely lifted a few academic eyebrows, but during ancient Egypt, it would have been epic. When scientists at the Manchester Museum scanned 800 animal mummies, one-third proved to be empty of skeletal remains. When worshipers wanted to connect with a certain animal god, they bought a related mummified creature as an offering. The faithful fully expected a wrapped cat to contain a dead kitty. As it turned out, the fervently religious nation’s demand couldn’t be met. Perhaps the profit-minded sellers didn’t want to let a good opportunity go, but the researchers believe the deception wasn’t so much forgery-orientated as it was to supply people with a religious experience. There just wasn’t enough time or animals to match the rapid sales. To speed things up, the beautifully crafted mummies were secretly filled with something linked to that animal, such as nest stuffing and egg shells for birds.

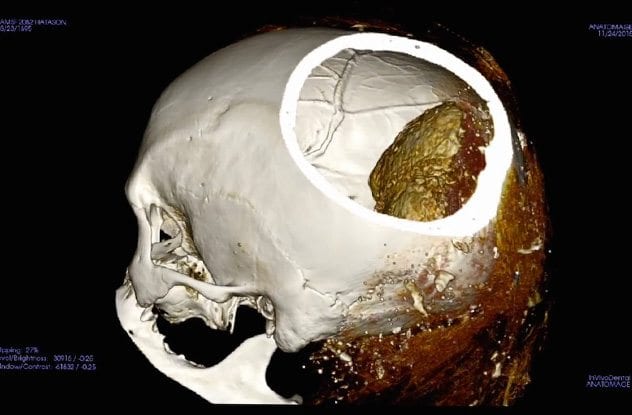

8The Sand Skull

A 3,200-year-old Egyptian mummy named Hatason sparked serious scientific interest after a scan. She died between 1700–1000 BC, a time when brains stayed intact during mummification. Adding material inside the skull cavity while it still contained gray matter is unheard of, but somebody forced a substance into her head. Strangely, the skull appears to be stuffed with dark sand. The woman was likely a citizen experimented on by a mortician. It’s hard to tell, since few mummies remain from that era and not a lot is known about her—or if she’s even a woman. Pelvic bones can reveal sex, but Hatason’s is crushed. The skull appears to be female. The coffin depicts a woman wearing the clothing of a standard citizen but there’s no way to prove it was hers. The mummy, currently in San Francisco, was removed from Egypt in the 1800s when buyers switched coffins as the need arose.

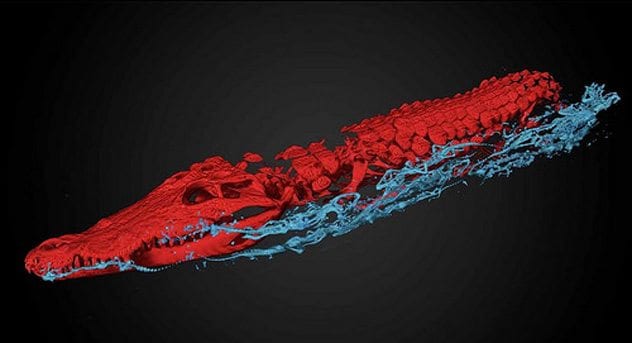

7Sobek Surprise

At the Dutch National Museum is a wrapped “crocodile.” Measuring three meters long, a previous scan revealed it contained two of the fearsome reptiles shaped as one giant croc about 3,000 years ago. In 2016, the mummy was sent to an Amsterdam medical center to undergo a cutting edge 3-D CT scan. The images were extraordinary. Egyptologists expected nothing new, but dozens of previously undetected bundles appeared to be tucked away between the wrappings. Closer examination proved that they were all individually bandaged baby crocodiles. While not unique, this type of mummy is extremely rare, and the Dutch one is also in superb condition. It would’ve made a great offering to the Egyptian crocodile god Sobek, which was probably what it was created for. The idea behind the strange arrangement is not clear. Experts suspect the different ages of the animals could be symbolic of rejuvenation after death.

6Practical Prosthetics

Looking at old personal items, it can be hard to discern which had a practical or cosmetic use. This holds true for ancient Egypt. Burial preparations often included false body parts, even when the deceased had no amputations. Recently, the University of Manchester strapped a special kind of replica on volunteers lacking a right big toe. The recreations copied two Egyptian artifacts that may be the first known prosthetics. Respectively, the toe sets consist of cartonnage (before 600 BC) and wood and leather (950–710 BC). The second was found on a Luxor mummy’s foot. Signs of long-term use hinted at prosthetics in the truest sense and not burial props. The volunteers went barefoot then wore the toes, with and without authentically remade Egyptian sandals. The study revealed that both devices were highly successful replacements for real toes and removed the crippling pressure traditional sandals would’ve caused.

5Rediscovery Of C1bi

In 1985, hikers found a body on Argentina’s Aconcagua mountain. The child, dead for five centuries, turned out to be an Incan boy killed during a sacrifice. The height at which he died, 5,300 meters above sea level, provided extreme dryness, and the seven-year-old mummified naturally. His good condition allowed geneticists to extract his entire mitochondrial genome. The DNA placed the boy in a genetic group called C1b, an ancient Paleoindian lineage older than 18,000 years. However, he didn’t match any of the plentiful subgroups dividing up the population. Researchers created a new one, called it C1bi, and scoured databases for more members of this lost line. Only four turned up. Three were from modern Peruvians and Bolivians. The last belonged to a person of the pre-Inca Wari Empire of Peru. An estimated 90 percent of native South Americans perished during the Spanish conquest. This genetic annihilation is behind C1bi’s scarcity today and also why it remained unknown until the discovery of the Aconcagua boy.

4The Hathor Tattoos

Egyptologists once believed priestesses were painted with images, not tattooed. A well-preserved woman changed that. Cedric Gobeil, a Canadian researcher working in Egypt since 2013, noticed dark shapes on the body and dismissed it as embalming residue. However, when the 3,300-year-old skin was extended with imaging software, the historic tattoos reappeared. They are the only depictions of recognizable things, not just shapes, ever found on a dynastic Egyptian. Lotus flowers, animals including cows and snakes, as well as symbols are part of 30 tattoos adorning the upper body and hips. Nobody knows what the full collection looked like. Her head and legs have never been found. Gobeil believes the skin art marked her as a priestess of the goddess Hathor, since several of the images are linked to this deity. That alone makes it a unique case. She’s also the first proof that murals showing figures with recognizable objects as body decorations are depictions of tattooed Egyptians.

3The Age Of Smallpox

In the crypt of a Lithuanian church, the remains of a toddler yielded the oldest traces of the smallpox virus. The first human disease to be wiped out with vaccination, the origins of smallpox remains a mystery. For a long time, it was thought to be a millennia-old disease that even plagued the Egyptians, when the latter provided a few pockmarked mummies. The Lithuanian discovery challenged this when analysis concluded the virus was only a few hundred years old. By comparing the 360-year-old strain from the child against all the known mutations, researchers determined they shared a single ancestor that first appeared sometime between 1588–1645. Had smallpox been thousands of years old, there would’ve been a significant increase in the number of strains, but the variety simply isn’t there. Some Egyptian mummies dating back thousands of years do have the trademark scarring, but measles and chickenpox could also have been responsible.

2The Cladh Hallan Burials

A decade ago, scientists were excavating a buried 3,000-year-old couple from the prehistoric village of Cladh Hallan, Scotland. Things didn’t get weird until one man noticed the female mummy’s jaw looked out of sorts, like it didn’t fit. DNA tests told a macabre story. The pair had been pieced together from parts belonging to six unrelated people. Those assembling the woman date back to the same time period, but her male counterpart’s contributors died at different times, some hundreds of years apart. Even their burial took centuries to complete. First they were placed in a peat bog until they were mummified and were then reburied at the village, 300–600 years later. Interred in the fetal position, all soft tissue was destroyed by the soil of their new grave. It remains a riddle why the villagers went through all that trouble.

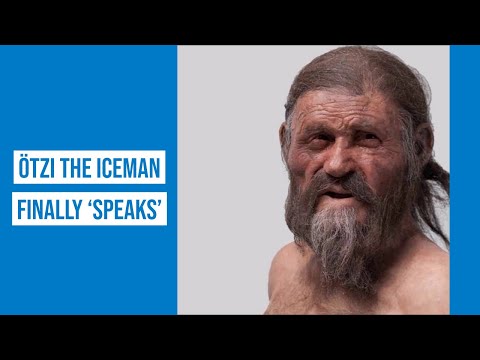

1Otzi Speaks

The superstar of the mummy world is undoubtedly Otzi. German tourists discovered him 25 years ago in South Tyrol, Italy. Researchers already determined his last meal, that he might have been murdered, looked at his DNA, tattoos, and health, then famously recreated his looks. In 2016, they finally returned Otzi’s voice. The team faced several obstacles in the quest to hear him speak. One arm is flung across his throat, obstructing an examination. The tongue bone was also incomplete. An MRI scanner was preferred for its greater detail, but the body’s fragility meant it couldn’t be moved. After the scientists settled on a CT scan, Otzi’s vocal tract was inspected, and the tongue bone was recreated virtually. With the help of additional software and mathematical models, sound came to life. It ranged between 100 and 150 Hz, normal for a human male. Since researchers don’t know how vocal cord tension and soft tissues affected his speech, his true speaking voice cannot be recreated. However, the tone of his vowels can, and it reveals a man sounding almost like a heavy smoker. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages