10 Accidental Inventions That Changed The World

10 The bathing machine

The idea of organized leisure took hold in England during the Industrial Revolution. Belief in the healthy properties of sea air encouraged the rise of the modern summer vacation, but sea bathing became a dilemma in the face of emerging Victorian prudishness. To discourage intimacy between bathers of opposite sexes, beaches became gender-segregated, and bathing machines soon crowded England’s fashionable resorts. These enclosed cabins allowed for changing into the conservative bathing suits of the day, and could be wheeled into the surf, preventing unsightly displays of naked flesh. As late as 1911, signs at one English seaside town warned that “No female over eight years shall bathe from any machine except within the bounds marked for females,” and “Bathing dresses must extend from the neck to the knees.” But as the twentieth century progressed, the once-scandalous practice of mixed bathing became widely accepted. The bathing machine became a throwback, but without this quaint contraption, the beloved English seaside holiday might never have endured.[1]

9 The electric telegraph

Few devices changed the world as rapidly as the electric telegraph. On May 24, 1844, inventor Samuel F. B. Morse tapped out an encoded message before an astonished crowd of Washington lawmakers who had gathered for the demonstration. Forty miles away, his assistant in Baltimore received the Biblical text by wire: “It shall be said of Jacob and Israel, What hath God wrought!” Morse had invented the world’s first instantaneous technology of communication. A religious man, he later claimed that the first message “baptized the American Telegraph with the name of its author”: in other words, God. The telegraph rose in tandem with America’s railroads and hastened the industrial revolution, triggering the demise of the renowned Pony Express, among other unintended consequences. But in 1876, another invention eclipsed Morse’s remarkable technology. The age of the telephone had arrived.[2][3]

8 The Cylinder Phonograph

With the age of the telegraph came another innovation: the cylinder phonograph, invented by Thomas Edison in 1877. Edison was inspired both by the repetitive function of the telegraph and the revolutionary sound transmission of the telephone to create his new recording device. While Samuel Morse baptized his electric telegraph with “What hath God wrought!” Edison’s first message on his new machine was decidedly less dramatic: the inventor was reportedly elated to hear his own recitation of the nursery rhyme “Mary had a little lamb.” The earliest commercial medium of its type, Edison’s phonograph recorded on paraffin paper cylinders embossed by a needle and diaphragm. Pre-recorded phonograph cylinders were soon available commercially, the crackly ancestor of today’s CDs and MP4s. The paraffin cylinders were soon replaced by more durable metal cylinders covered in tin foil, but these likewise suffered rapid deterioration, so the tin foil covering was finally replaced with hard wax coating. The Edison Speaking Phonograph Company began exhibiting the new technology in 1878, and Edison made a tidy profit on the windfall ($10,000 manufacturing and sales rights, plus 20 percent of all ensuing profit). Bubbling with visionary ideas, he imagined some possible uses for the phonograph in a June, 1878 feature for North American Review. In addition to the recording and playback features, he suggested, phonographs could be used for dictating letters, creating speaking books for the blind, compiling audio family scrapbooks, recording last messages from the dying, and even as an early form of telephone voicemail. Though many of these ideas were ahead of their time, Edison soon moved on to other projects, including his incandescent electric lamp. Nevertheless, the Edison Company continued to churn out cylinder recordings until 1929, though rendered obsolete by the phonograph discs popularized by the Columbia and Victor recording companies in the early twentieth century.[4]

7 Hydrogen airships

Forget airplanes. For much of the twentieth century, gas bags were the future of flight; or more precisely, dirigible (steerable) powered airships, filled with the lightest, most abundant element on Earth. There was just one problem: hydrogen burns. The age of transatlantic airships met a fiery end in 1937, when the 800-foot Zeppelin Hindenburg crashed in New Jersey, killing 36 people on board. Though helium gas is a safer alternative, it was too rare and expensive to keep airship travel afloat. Curiously, hydrogen airships may be looking at a revival, at least for freight. A 2019 scientific paper envisioned new airships 10 times larger than the Hindenburg carrying huge cargoes in the upper atmosphere. These projected mega-ships would be unmanned drones, constructed from modern fire-retardant materials such as carbon fiber. The benefits in terms of greenhouse gas reduction would be great, but it remains to be seen if this bold vision will take flight.[5][6]

6 Daguerreotype photography

New is not always better when it comes to technology. A case in point is the Daguerreotype, invented by Frenchman Louis Daguerre in 1839. Like Samuel Morse, Daguerre began his career as a professional painter, but fascination with the science and technology of optics led him from the studio to the laboratory. There he invented the world’s first successful photographic technique, which in key respects remains unmatched even by today’s digital photography. Each Daguerreotype was produced using a silver-plated copper sheet infused with iodine vapors, noxious mercury fumes, then finally stabilized with salt water or sodium thiosulfate. Every image was unique, and being un-pixelated, astounding in resolution (by contrast, even high-res digital imagery becomes distorted by magnification). Tragically, Daguerre’s studio burned down in 1839, claiming the bulk of his records and many early images. Today only around two-dozen confirmed photographs by Daguerre survive, including landscapes, portraits, and still lives. Then, around the mid-nineteenth century, the Daguerreotype started losing ground to the negative-based wet-collodion process (invented in 1851, the year Daguerre died). This new technique produced a cheaper, more reproducible end product, poorer in quality but more convenient.[7][8][9] 10 Victorian Inventions We Just Can’t Do Without

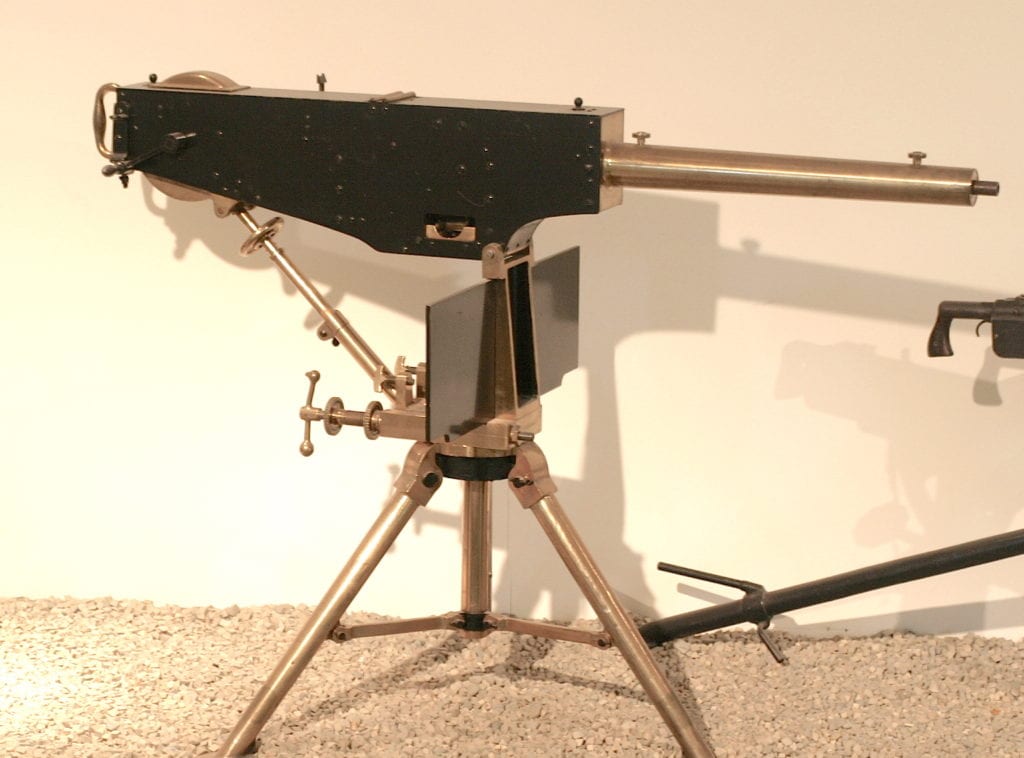

5 The Maxim Gun

“Whatever happens, we have got/ The Maxim gun and they have not,” was the gruesome boast of the British Empire, describing its ultimate weapon of conquest. The world’s first recoil-operated machine gun was invented by American Hiram Maxim in 1884, and transformed the face of warfare. Future Prime Minister Winston Churchill witnessed its murderous power at the 1894 Battle of Omdurman. His small British force routed 40,000 Sudanese warriors who “sank down in tangled heaps” before the Maxim Gun’s withering fire. After five hours, some 10,000 Sudanese were killed, with only 20 British dead. Though prone to jamming and eventually phased out by more efficient weaponry, the Maxim Gun remained in western military service through World War One, the first major conflict where opposing armies slaughtered each other with automatic fire.[10]

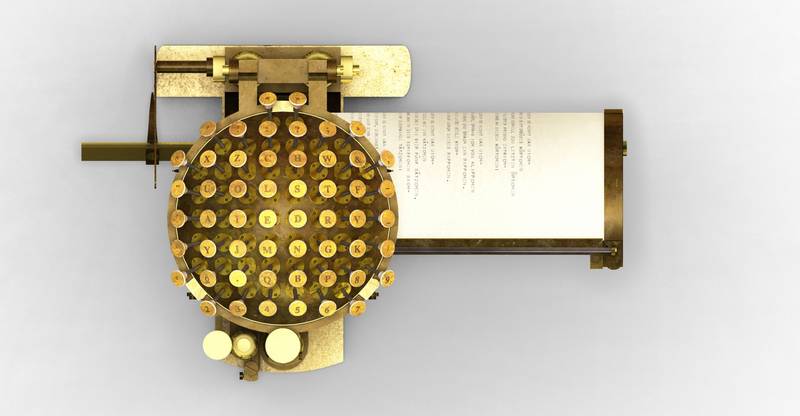

4 The Malling-Hansen Writing Ball

Though collected by enthusiasts, the manual typewriter is as obsolete as the quill pen. Hard to imagine, then, the appeal these clunking devices once enjoyed. The first commercial model was the Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, invented in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1865. A squat curiosity resembling a mechanical hedgehog, the Writing Ball was the MacBook Pro of its day. Its biggest fan was German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, whose poor eyesight prompted him in 1881 to purchase a more efficient means for his prolific writing. So besotted was Nietzsche, the man even composed an ode to his device:[11] The Writing Ball is a thing like me: Made of iron yet easily twisted on journeys. Patience and tact are required in abundance As well as fine fingers to use it.

3 VHS recording

For those of a certain generation, few technologies are as nostalgic as the VHS cassette tape, developed in 1970s Japan. Like Edison’s phonograph, VHS was multi-purpose: retailed in pre-recorded format or blank tapes suitable for recording The Dukes of Hazzard over your sister’s graduation ceremony. Like other relics on this list, VHS is still prized by enthusiasts, and its decline came later than we often remember. American consumers encountered the sleek DVD in 1997, but both formats coexisted for several years until the demise of mass VHS production. An August 2005 Washington Post article thus proclaimed that VHS “has died at the age of 29,” while noting that 94.7 million US households still owned VCR players. Later that year, Revenge of the Sith became the first Star Wars movie released exclusively in DVD home video format. Ironically, 2005 also introduced cult horror movie The Ring Two, reprising the basic premise of 2003’s original The Ring, which revolved around a haunted VHS recording. Let’s face it: a haunted DVD wouldn’t have scared anyone.[12]

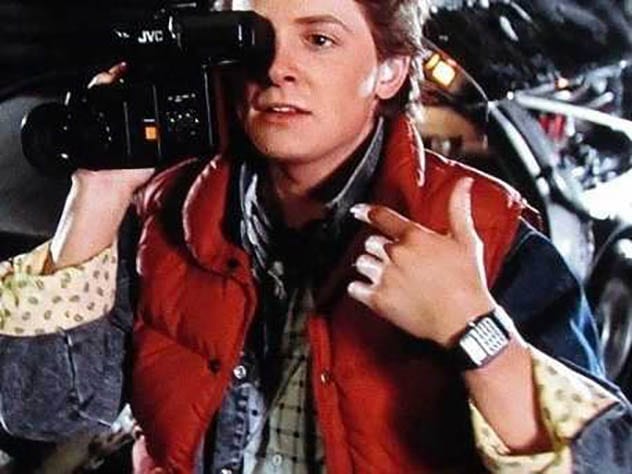

2 The calculator watch

Back in the eighties, nothing said “it’s hip to be square” like owning a calculator watch. These gadgets were around since the 1970s, part of a broader craze that included wrist-portable TV and video games. But Casio’s Databank line launched in 1983 propelled them to new heights. Iconic status was assured two years later, when Marty McFly sported his Casio Databank CA53W Twincept in Back to the Future (1985). Casio’s Databank line is still manufactured today, to the delight of Generation Xers. The calculator watch became more of a retro fashion statement than a practical device, but has outlasted that other tech icon of Back to the Future, the short-lived DMC DeLorean sports car. And for better or worse, the Casio Databank anticipated today’s mania for Fitbits, Google Smartwatches, and other wearable technology.[13]

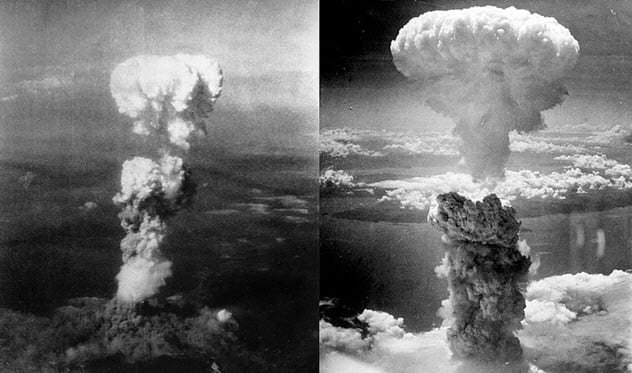

1 The atomic bomb

“Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds”: nuclear scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer, witnessing the first atomic bomb test, July 16, 1945. Historians still debate whether the 1945 destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War Two was justified, or simply wanton destruction. But one terrifying fact remains: the atomic bombs which killed some 200,000 Japanese civilians pale beside later weapons of mass destruction able to kill millions in a flash. Scientists from the US Manhattan Project, which developed the A-bomb, were among the first to warn against the still deadlier hydrogen, or H-bomb. In a September 1945 letter, physicist Arthur Compton even argued that he “preferred defeat in war to victory obtained at the expense of the enormous human disaster that would be caused by its determined use.” Time will tell how long the age of nuclear weaponry endures, and how it ends.[14][15] 10 Food Inventions That Changed The Way We Eat Breakfast About The Author: A native of the UK and naturalized US citizen, Matthew Smith lives in Cincinnati, Ohio with his wife, daughter, and three cats. A history professor by day, he has spent this summer learning how to teach online, and connecting his passion for history to a wide readership outside the confines of academia.