Top 10 Things Your Ancestors Did Better Than You

10 Typing

Cell phones have been around since 1984, but texting has only been available since the late 1990’s. In fact, cell phones – then called “mobile” phones – didn’t have full keyboards until the Nokia 900i Communicator was issued in 1997. Now? According to a 2017 texting study (that did not include app-to-app messaging), more than 900 million texts are sent every hour worldwide with a whopping 22 billion daily. Watch this video on YouTube Believing their students learned typing on their cell phones and laptops, schools began to remove from their already busy curriculums what had been a staple on them for a century: the typing class. Back in the day, students were usually taught “touch typing” or “keyboarding” that was reportedly devised by a court stenographer, Frank McGurrin, in 1888. The students were taught to start typing with their fingers touching specific keys – called the “home” row —at the center of an English keyboard. With their fingers resting on the A, S, D, F, J, K, L and ; keys, the students then teach muscle memory to their fingers, finding the other keys from their position relative to the home row. In this way, they could achieve better than 100 words-per-minute. Recently teachers have noticed that students without typing skills, develop their own idiosyncratic peck and hunt method. One teacher in Washington D.C. noted that it took her elementary school students as much as 10 minutes to type a Google search. There’s a meme that circulated of a student using their texting thumbs to peck at a keyboard. The meme isn’t funny anymore. But speed isn’t the only benefit to touch typing. Such a technique is an example of cognitive automaticity, a skill where the person does something without conscious attention to the process. Driving, riding a bike or reading (without sounding out the words) are other examples. In typing, this process frees the mind to think about sentence structure, synonyms or the correct way to express an idea rather than where the question mark is located.

9 Cursive

The argument for not teaching cursive is that the vast majority of writing we do now days are on keyboards. And in those rare occasions when we need to put pen to paper, printing is far less complex. All true. What is lost, according to experts, are the neural pathways cursive writing stimulates in our brains. Cursive writing invigorates the interplay between right and left cerebral hemispheres, increasing mental acuity. Comparisons of MRI or CT scans of people typing and writing cursive show, according to a researcher, “that sequential finger movements used in handwriting activated massive regions of the brain involved in thinking, language, and working memory.” Not so with keyboarding. The “working memory” advantage is almost immediate for a student. Taking class notes in cursive forces the student to process the content and reframe it, increasing retention and understanding. Studies have shown that cursive notes will help a student retain the material a week longer then if they typed or printed them. Studies have also shown that repetition of the correct pressure and angle of the pen to paper and planning where and how to start the word for a fluid left to right motion builds physical and spatial awareness. This creates neural pathways for other sensory skills such as buttoning, fastening and tying shoes. Repetition of joining words develops muscle memory of common sequences (“i before e, except after c”), spacing and spelling. This is similar to the way a pianist learns muscle memory through repetition. For children with dyslexia (inversion of letters in words), dysphagia (difficulty speaking) or attention deficits, printing is more challenging than cursive because of the start and stop motions of the former. Some letters in printing – such as b and d – can look too similar to the struggling child. The inability to write cursive means a person is likely unable to read cursive, leaving them functionally illiterate in one aspect of their own language. They would struggle, for instance, with reading the original Declaration of Independence or the Constitution. A cursive signature is harder to forge than a printed one. Most important of all, cursive has also been shown to increase writing speed and self-discipline, which can lead to heightened self-esteem one acquires by mastering a skill.

8 Shop

Since the late 1990’s, education experts have identified a disquieting trend: a high percentage of kids 16 to 24 are neither in school nor working. A hallmark that a child is transitioning from his/her teens to adulthood are either getting a job or seeking a higher education, and if they’re not, child psychologists call them “disconnected.” Not only are these kids not developing the maturity to handle life’s problems, they’re not developing the education or work history to make even a decent living. Nor do they have social and employment networks that will advance them in the jobs they do acquire. Social media and gaming have only exacerbated this problem and it’s easy to brow beat these kids, call them “deadbeats” and snarl at them to get a job. But this may not be a clear case of laziness. In an appalling irony, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002 to 2015 was meant to stem this trend, increasing the employability of kids in the workforce, but may have done the opposite. In particular, NCLB was meant to level the playing field for minorities, the impoverished, and children with special needs or limited English-speaking skills. While NCLB could claim some success, not so with the percentage of disconnected kids. In 2000, that percentage stood at 3.9%. By 2010 it rose to 7.5%. Nor did the NCLB’s successor, Every Student Succeeds Act (2016 to present), improve it: one 2018 study found 18% of 18 to 24-year-olds were disconnected. Nor have we seen the hoped-for decline in minority or impoverished disconnected kids. One repeated criticism of NCLB and ESS was that it foisted narrow academic standards on schools and their students in the guise of standardized testing, with the time-constrained teachers forced to “teach to the test.” This left no room for school classes not tested such as the shop class. As a result, shop nearly went extinct. In the past shop class taught everything from how to use tools, to household maintenance to auto repair to making things with your hands using wood, metal, pottery and, more recently, 3D printers. It was an artistic outlet for those who did not play an instrument or on a stage. And it was an introduction to employment in the trades. We’ve long needed people to work in trade occupations such as electricians, paramedics, plumbers, chefs, carpenters, mechanics, engineers and construction workers. They are arguably just as important as jobs that require a higher education. But kids are not told that. In the rush to pigeon-hole everyone into college-preparatory, kids were often steered away from the trades, even if their skills should have led them directly toward them. These kids are often told that because they struggled in the classroom, they were somehow inferior from the college-bound kids, that they were destined for failure. Sadly, some parents have taken up this mantra, bruising their own child’s self-esteem needlessly. Anyone who has investigated the wages of an electrician or plumber (without acquiring college debt) know this is false.

7 Latin

At the turn of the 20th century, more than 50% of all U.S. public high school students took Latin as their foreign language requirement, largely because Latin was needed for college admission. In 1958, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act which, as the title implies, was focused on preparing kids for subjects relevant to national defense such as math and science. Latin was not an approved subject. This led to a dramatic drop in enrolment in Latin courses: 702,000 high schoolers in 1962 to 150,000 in 1976. While there has been a recent resurgence in secondary school Latin, it is still relegated mostly to colleges and college preparatory schools. Watch this video on YouTube Latin has often been described as a dead language, but that’s a misnomer. It’s true that few outside of the world of Harry Potter speak Latin, but 60% of all English words and 90% of all vocabulary in technology and science are rooted in Latin or Greek. Studying Latin roots decodes English and Math (another language that, like Latin, relies heavily on logic, orderly thinking, and attention to detail) for the student. One study compared test scores of Latin students to those who took Spanish, French and German. Latin students scored ahead of the other students in English literacy by one year and math by 9 months. Because Latin requires students to break down grammatical structures and parts of speech, it prepares students for tackling other languages. Once the student is familiar with concepts such as grammatical gender, conjugated verbs, agreement and inflected nouns, they can move onto the same concepts in other languages, even tough ones like Russian. Some 80% of the words in romance languages (Italian, French, Spanish, Romanian and Portuguese) and most of their lexicon, structure and grammar come from Latin. We’ve already talked about how most scientific jargon is rooted in Latin (and Greek), so it should surprise no one that learning Latin is highly beneficial to scientific and medical students. But legal vocabulary is also heavily rooted in Latin. And while computer languages are varied and ever changing, all are based on logical sequences, just like Latin.

6 Cooking

Home Economics classes were originally added to curriculums to train women in the skills to work outside the home, but by the 1960’s and 70’s it was seen as a vehicle to keep women home and out of the workplace. This is in part because of the segregated nature of the course: it was mandatory for girls, just as shop was for boys. But the decline of home economics courses came less at the hands of perception and more at the hands of college recruiters. In the school year that began in 1970, women were the recipients of only 9.1% of all business bachelor degrees. In 1984 it was 45%, and in 2001 it was 50%. In 2017, women received 61% or better of bachelor degrees in 9 out of 16 academic fields. Fifty-six percent of all U.S. undergraduate students are now female. Sensing this trend, educators began to focus on prepping for college rather than for prepping for home life, whether for boys or girls. This is despite the fact that some 70% of all high school grads will need college prep, while almost 100%—grads or not grads—will need home prep. “In higher ed[ucation], there is definitely an air of: ‘How does this develop marketable skills?’ Which, it seems, has trickled down into the K-to-12 arena,” said one educator. “Teaching to the test and metrics have never been more important, and sewing and cooking don’t qualify.” With these priorities together with budget cuts and time constraints, home economics – now referred to as “Family and Consumer Sciences”- is usually the first course cut from the curriculum. Back in the day, Home Economics taught just what the name implies: home budgeting, opening and operating a bank account, paying bills, filing taxes, benefits and traps of credit cards, and saving for retirement. It was also – much like shop – an umbrella for a myriad of subjects ranging from sewing, raising children and cooking. With these courses going the way of the Dodo in secondary education, many are taking “adulating” classes in college. This would be fine if every adult that needs them could also afford college courses. But that isn’t the case. One subject taught in Home Economics that is missed more than others is cooking. Millennials in particular have been criticized for never cooking anything that doesn’t come from a box or freezer and go directly into a microwave. They are more likely than previous generations to pick up something at a drive thru or restaurant. This, of course, is very unhealthy and contributes to obesity. The act of cooking itself burns calories, and changes the mindset from processed foods to fresher, more nutritious eats. As the cook prepares the food, he or she takes ownership of it, making it more likely they will eat it and store leftovers. And cooking food is considerably less expensive than processed food whether from the freezer or restaurant.

5 Interpersonal Communication

A perusal of blogs and feeds on the subject of technology in the classroom reveals a heated argument. On one side, many defend teachers and schools who insist their students check their cell phones at the door. On the other side there are plenty of rants from students and parents who insists such practices are antiquated and those students need to be in constant touch with the outside world. But the statistics are alarming. Children 8 to 10-years-old are exposed to media 8 hours of every day, half of their waking hours. That number rises to 9 hours for teens. Watch this video on YouTube The results are discouraging. The average person shifts their attention from cell to laptop or tablet 21 times an hour, training the human brain to have a shorter attention span (8 seconds) than a goldfish (9 seconds). While older adults have adapted to balancing screen interactions with face-to-face ones, millennials have quite a bit less experience with the latter. One place this is evident is in conflict resolution. “I can’t imagine these kids sitting down in an interview and having a reciprocal conversation easily,” said Child Psychologist Melissa Ortega. ”They haven’t had these years of learning about awkward pauses. Being able to tolerate the discomfort is not something they’re going to be used to….” Worse, a lack of face-to-face interactions means millennials have a harder time reading the emotions on the other person’s continence. Nor are they aware of simple communication essentials, such as eye contact. In order to establish an emotional connection with another person, eye contact should be maintained for 60% to 70% of a conversation. But today people maintain it as little as 30% of a conversation. In a 2018 survey, 80% of executives and hiring managers say the number one skill they look for in a candidate is good speaking skills. They also said fewer than 50% of their candidates had what they’re looking for. So if the priority of schools is the employability of our kids, the schools are failing. At one time, the hated speech class gave students the opportunity to hone their verbal skills, but this is another course crowded out of curriculums. Decades ago there was another class known as Etiquette which essentially taught good manners. Many would say teaching manners should be taught at home. Except they’re not. In Etiquette class, students learned everything from how to tie a tie, to the proper grip for a handshake, to the importance of eye contact. Teachers have tried to pick up the slack by insisting on in-class presentations, but they are equally hated. In one tweet from a 15-year-old, in-class presentations were equivalent to bullying the socially anxious and advocated giving students a choice whether to present. The tweet was retweeted 130,000 times and received a half million likes. One person responded that students should also not be forced to raise a hand and participate in class. One wonders what job either of these two teens expect to find that will exempt them from verbal communication simply because they’re anxious. Or what kind of personal relationships they may expect if they don’t verbally participate.

4 Civics

Civics used to be a course taught in middle school along with an American Government course in high school. Then education ran smack into the 60’s, Vietnam and Watergate and Americans no longer had the enthusiasm for courses about their government. Schools, under what became known as “new social studies,” taught specific social sciences like economics and psychology. But not civics. By 1986, fully half of all high school juniors said they had not taken a course on American government. The next year, there was a movement to reintroduce civics into the classroom. Watch this video on YouTube Today civics is typically taught in high school, but the debate over civics literacy is still ongoing. In April 2020, the governing body for Purdue University in Indiana considered a resolution to require their students to take a civics literacy test before they graduate. Many members questioned why such an onerous requirement should be foisted on their seniors and why they’d be forced to study something that should have been taught in K-12. Indiana does require a semester of high school civics, but they are not among the 17 states that require a civics literacy exam to graduate high school. Every state requires some civic or social studies “course work,” but the quality of that instruction is, at best, uneven. For instance, 9 states require a full high school year of civics, 30 require a semester and the other 11 do not mandate how much civics is taught. While 25 states allow credit for the students to volunteer or be civically engaged in their community, only one state – Maryland – requires it for high school graduation. Just 31 states require what’s called a “full curriculum” for civics, which includes “Explanation/Comparison of Democracy,” “The Constitution and Bill of Rights,” and “Public Participation.” And it shows. One 2016 survey showed that only 26% of American adults could name all 3 branches of their own government. A 2018 survey demonstrated that 2 out of 3 Americans would flunk the U.S. citizenship test. One survey of college grads discovered that most couldn’t identify the origin of the separation of powers, the father of the Constitution, or the term limits of members of Congress. Yet another survey found that one third of Americans couldn’t name any of the five fundamental rights found in the First Amendment. Some of the answers are not just sad, they’re laughable. Nearly 10% of college grads thought Judge Judy sat on the Supreme Court.And the cause of the Cold War? Some answered it was “climate change”.

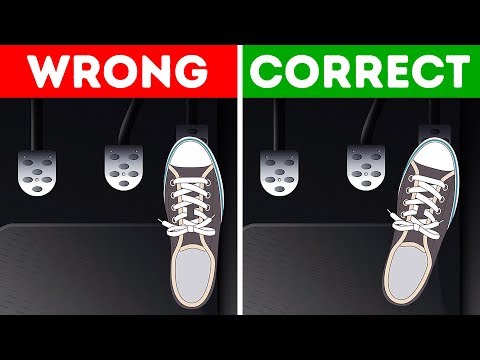

3 Driver’s Education

Back in the 1970’s, fully 95% of eligible high school students took driver’s education, typically during the summer between their sophomore and junior year. After a study in the early 1980’s questioned how much driver’s ed improved teen road safety, public funding decreased and school insurance premiums skyrocketed. Driver’s ed began to shift to private companies and online courses. The problem was that both private and online instruction weren’t (and still aren’t) consistently regulated, making them, as the president of AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety said, “faster, cheaper, but not necessarily better programs.” What’s more, not every teen can afford the fees for private instruction, which can be as much as $500. This is on top of paying for a vehicle, car insurance and gas. Which is why the number of high schoolers acquiring their driver’s license have been declining. Nationwide, the percentage of 16-year-olds without a driver’s license dropped from 46% in 1983 to 24% in 2016. During that same period the percentage of 19-year-olds sans a license fell from 87% to 69%. The hardest hit are the poor. Consider Kalamazoo, Michigan where 32% of its families live under the federal poverty level. Michigan began transitioning from public to private driver’s education in 2004 and. statewide the number of teens who obtained their license under 18 dropped 5% between 2004 and 2016. In Kalamazoo it dropped 13%. Another reason is that around the same time states began implementing graduated licensing laws which grant driving privileges in stages and prohibits certain risky driving behaviors such as driving at night and with other teens. These graduated stages usually require a set number of hours driving under the supervision of a parent or driving instructor. That is until they turn 18. Some teens are simply waiting until that age so that they won’t have to drive under supervision or pay for instruction. Which means they may be on the road without any driving instruction at all. To off-set this potential for disaster, some states have considered requiring some form of supervision until 21, which will not be popular. The solution, of course, is to hand driver’s education back to the high schools and do away with the often complicated and inconsistent graduated system. There are a number of benefits school-sponsored driver’s ed have. An approved curriculum could include teaching kids how to change a tire, check the oil, and how to find important parts of the vehicle. School driver’s ed students are typically younger, and experience-based instruction will stick with them longer. And school-sponsored driver’s ed is usually group-based, where an instructor takes two or three kids on the road to practice their skills. This allows students to learn not just from their own experience, but from their classmates’.

2 Play

Most of the items on this list have been on the secondary end of the education spectrum, but the entire spectrum has been affected by curriculum changes. Nowhere has this been more evident than in the kindergarten classroom and playground. In 2019, kindergarten teachers in Brookline, Massachusetts, publicly criticized their districts policies to squeeze out play-time in their classes for a more rigid, direct test-driven instruction. One teacher recalled that just a decade before her kids had 2 half hour recesses and class time that was a mix of games and social and emotional exercises. Now they have only 1 recess and set blocks of goal-driven lessons more prevalent in upper class levels. The children are now more stressed and have little love for school. To be fair, Brookline school administrators state the reason for the changes was their concern that low-income children did not attend pre-school and would not have the reading skills that pre-school grads had. “We were very much aware that if children didn’t read fluently by third grade that the chances of catching up would be almost insurmountable,” said Superintendent Andrew Bott. But the research just does not support their hopes for better reading comprehension. As far back as the 1970’s, a German study of the graduates of 50 play-based kindergartens were compared to 50 direct-instruction kindergartens. There were initial positive results for the direct-instruction group, but by the 4th grade they were performing significantly worse than the play-based kids in math and reading. They were also less mature emotionally and socially. Two studies in America of low-income kids had similar results: initial gains that disappeared and even reversed a few years later. One study actually followed up with the kids at ages 15 and 23 and found no difference academically to play-based kids, but found significant differences emotionally and socially. Those in the direct-instruction group at 23 were more likely to have “friction” with other people, were less likely to be married and living with their spouse, and were more likely to have an arrest record (39% compared to 14% in the other group). Some 19% of those arrests were for assault with a deadly weapon compared to 0% in the other group. Experts believe that classroom environments where the kindergarteners decide on their own activities and resolve conflict through negotiation develop life-long positive social skills. Classes with both unstructured free play and guided play with exercises to stimulate creativity and curiosity help the kids develop into a whole person. In this environment, kids learn to regulate their own emotions and their responses to others, to have and express empathy, and it even elevates the child’s language skills. In response to the protests from Brookline, teachers from around the country sent their own anecdotal experiences demonstrating that the issue is not limited to Brookline. One kindergarten teacher wrote: “Words that have come out of my mouth this fall: ‘We do NOT play in kindergarten. Do not do that again!’ (to a student building a very cool 3D scorpion with the math blocks instead of completing his assigned task to practice addition.) ; ‘No, I cannot read Pete the Cat to you. We have to do our reading’ (90 minutes of a scripted daily lesson); ‘Those clips (hanging from the ceiling) are for when we do art. No, we cannot do any art. We have to do our reading lesson’ (my kinders get to go to a 40-minute art class once a month); ‘No, you cannot look at the books/play with the toys’ (literacy toys and games). ‘No, we cannot do a science experiment. We have to do our reading.’ ‘No, we cannot color. We have to do our reading.” … I hate my job. Love my kids—hate the curriculum. But I cannot afford to quit. Too close to retirement to start over.”

1 Logic or Critical Thinking

At one time, high schools used to have a course – usually an elective—known as Critical Thinking or, sometimes, simply Logic. In this course, students were not taught what to think, but how to think. They were taught to question everything they read or heard, to accept nothing at face value, and to suspend judgment until they’d heard all sides of an argument. Most of all they were taught to avoid “group” think. They had discussions on the different interpretations of movies, TV shows and other cultural mediums. They were taught structured analysis and given exercises on debatable subjects such as current events, politics, history, natural sciences, economics, sociology, even religion, and allowed a safe place to debate them. Known in psychologist circles as “soft skills, a 2013 Gallop Poll found that 80% of Americans wished K-12 kids would be taught these skills. Watch this video on YouTube The course was dropped from most curriculums because there simply wasn’t enough time. State and federal education departments mandate so many subjects to be taught, that courses on logic were forced out. A few teachers continued to teach critical thinking within their disciplines, but with more and more regulations, even their disciplines had to be taught swiftly and superficially, assuring that both the teacher and student were bored tearless. Time constraints meant that whatever was said by the teacher or written in the texts had to be taken at face value, without question, without even considering alternate explanations or theories. The results are generations that consider any blog or news feed uncritically, swallowing it whole (or rejecting it outright due to the personal opinions of the creator). Generations who adopt the fashionable mindset without considering the repercussions of it. Generations who want to punish alternate viewpoints rather than explore the possibility they might have validity. Generations who consider disagreements a personal affront to their self-esteem instead of just someone’s opinion. No one school course could change all of that, but everything starts with a first step. Top 10 Ways College Makes You Dumb About The Author: Steve is the New York Times Bestselling author of “366 Days in Abraham Lincoln’s Presidency” and a frequent Listverse contributor